Chapter 6

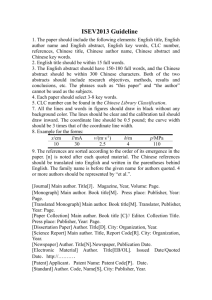

advertisement