U.S. versus EU Competition Policy: The Boeing

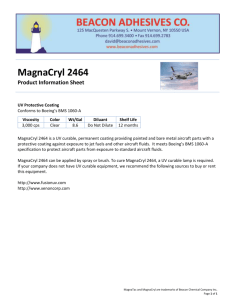

advertisement