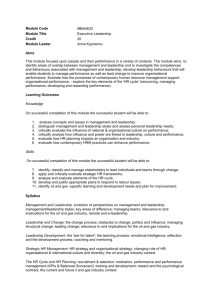

- ePrints Soton

advertisement