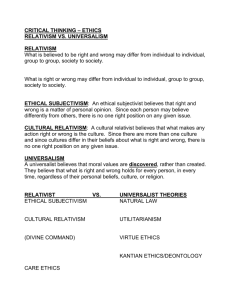

Relativism about Truth Itself

advertisement