Story in 1920s - Geological Society of America

advertisement

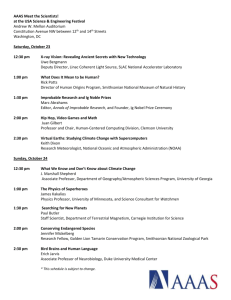

Ellis Yochelson sent in the abstract for this talk to GSA in June 2006. Shortly thereafter, Janice Goldblum (National Academy of Sciences archivist) and he discovered an evolution statement of the NAS from the 1920s. When I saw Ellis in July 2006, I told him about a resolution on evolution by the American Association for the Advancement of Science also from the early 20s. He and I discussed the paper at length, and he gave me copies of the documents and notes he had made. After Ellis died on August 30, I asked his daughter, Abby Yochelson (Library of Congress) if she wanted me to write up and present his paper. She agreed and provided additional notes he had made before his death. The paper is based on Ellis’s research with a few gaps filled by me. Any errors are mine. Michele Aldrich November 2006 Ellis’s story is set in the United States in the 1920s, a period of a rise in Christian fundamentalism and Biblical literalism. The story locale is the Smithsonian Castle (see slide), home of Smithsonian secretaries (CEOs) and assistants from 1853 to date, the National Academy of Sciences 1875-1930, and the AAAS, 1907-1946. These three DC scientific organizations created resolutions and statements about evolution in the early 1920s (see slide). The AAAS resolution was provoked by a paper given by William Bateson (see slide), an English geneticist, at the December 1921 AAAS meeting in Toronto, and published in SCIENCE (the AAAS’s official journal) shortly thereafter. Bateson questioned the exact mechanism of evolution, still uncertain to many scientists, but did not discredit the broad concept per se. Anti evolutionists used it that way despite his caveats. The AAAS Council undertook damage control, appointing a three man committee (see slide), all within easy train ride of each other. They were in related fields, two neontologists (Conklin and Davenport) and Henry Fairfield Osborn (see slide), of most interest to geologists. Osborn was a vertebrate paleontologist and President of the American Museum of Natural History. He had his own view of evolution, that it was guided, gradual, and continuous, all sharp differences from Bateson. In December 1922, the AAAS Council passed a resolution (see slide), which was published in SCIENCE in early 1923 (see slide). This document had an extended life: in May 1925, it was dusted off for the Scopes trial and release by Science News Service. The release was also published in SCIENCE but not the NY Times or the Washington Post. What did the AAAS resolution say? Because it was a resolution not a statement, it was brief and no evidence was presented in support of claims. There was no philosophical preamble about scientific truth or method and no mention of Darwin or Darwinism. The theory of evolution was endorsed as correct for the history of plants, animals, and man – the latter most troubling to Biblical literalists. It mentioned state restrictions on teaching of evolution and the Toronto meeting. The resolution stated that the general concept of evolution was thoroughly tested. The resolution closed with a declaration that attempts to stifle teaching of ANY scientific theory as well supported at this threatened progress of human welfare The NAS statement grew out of member discussions at the annual meetings in 1921. The Academy Council asked its President, Charles Doolittle Walcott, to appoint a Committee with representation from each NAS discipline section. Walcott (see slide) was President from 1917 to 1923. A paleontologist and Secretary of the Smithsonian at the time, he worked on the evolution of trilobites. Walcott believed that good Christians made good scientists because both sought the truth. The NAS Committee he appointed was nearly unworkable because of the section requirement - too big, too geographically spread out, and too disciplinarily diverse. Initially, the Committee said the NAS should not take a stand on the issue because the Academy existed foremost to support research, not education. However, the chairman John Mason Clarke (see slide), persuaded them otherwise. Clarke was state paleontologist of NY and faced a politically conservative legislature. As director of the state museum, he was concerned about the educational role of science, including that of the Academy. The Committee compromised, formulating a statement but declaring it should be held confidential until needed. In 1923, this action passed the membership (see slide). The Academy had no journal like SCIENCE; its PROCEEDINGS published scientific papers but not news. Furthermore, the AAAS’s public actions made NAS publicity on behalf of the American scientific community less necessary. The statement on evolution stayed unpublished and unknown until it was discovered by Janice Goldblum on a question from Ellis Yochelson. What did the NAS document say? Again, there was no mention of Darwin or natural selection. It had a long preamble about truth: knowledge of natural law THAT derived from investigation, not inspiration as did religious truth. There was a long history of opposition to the findings of investigation, such as the discovery of the roundness of earth and the fact that the sun, moon, and stars do not go around earth (but since the moon does go around the earth, perhaps it was just as well the Academy’s statement was not publicly circulated). The doctrine of organic evolution was known to the same degree of certainty as demonstrated by the continuity of life and development of organisms. Those who oppose it are ignorant, it concluded, and stifling research and education of scientific work retards the progress of civilization The Smithsonian statement grew out the need to respond to the Scopes trial in the summer of 1925 and was crafted by two assistant secretaries. Charles G. Abbot (see slide) was assistant secretary for the Astrophysical Observatory and acting director in Walcott’s absence. Walcott was in the field that summer; he commonly delegated duties to reliable staff and did not micromanage the results. Abbot was an astronomer who worried about “six days” of creation because he worked on variable stars and the long life of the universe. Alexander Wetmore (see slide) was assistant secretary in charge of the zoo in March 1925 and shortly thereafter in charge of the US National Museum. He was an ornithologist and avian paleontologist. Their statement survives as a poorcopy (see slide), mimeographed on three pages and attached to a cover letter (see slide) from Abbot to E. A. Blythe (about whom nothing further is known but Ellis probably would have tried to find research him). We don’t know how often it was used, and again, Ellis would have checked that. It was not published, even in the Smithsonian ANNUAL REPORT (see slide) for 1925 or 1926. These volumes were widely circulated and contained administrative reports as well as original scientific papers. What did this statement and cover letter say? That no scientific theory is conclusively proven, but that scientists disagree about details of all of them, including evolution. However, the broad concept of evolution sums up an array of otherwise isolated facts and stimulates further investigation. As with the earlier documents, there is no mention of Darwin. The Smithsonian claimed to present facts and offer the best explanation of them through its exhibits and correspondence. It did not take sides in rival theories (such as those of Bateson and Osborn). It offered facts supporting evolution, eleven in all. Several were geological (see slide) and others came from other sciences (see slide). It closed by saying that many Smithsonian scientists were also religiously devout. . These three statements contrast to more recent resolutions by scientific societies, including those by the AAAS and NAS, which are posted on the National Center for Science Education website (see slide) in the “Voices for Evolution” section. The argument for progress in fossils is seen by scientists as a value judgment rather than scientific fact. Many details of evolution contested in the 1920s have since been settled, and while arguments remain, they are not as great as between Osborn and Bateson because the “Modern Synthesis” brought those two sides together. The nature of evolution’s opponents has changed too. Creationists claim their theory as a science that belongs in science classrooms; it was this argument that the courts rejected, ruling that creationism is a religious theory that comes under the rules of church and state separation in public schools. Several people helped Ellis and me in the preparation of this paper. They are thanked in the last slide.