CHAPTER 1

From the Origins of Agriculture to the First

River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES

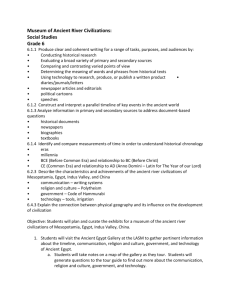

After studying this chapter students should be able to:

1.

Describe the ways in which early humans adapted to different environments and be able to

differentiate between hunter-gatherer and food-producing economies.

2.

Analyze the environmental causes and effects of the transition from hunter-gatherer to foodproducing economies.

3.

Describe the relationship between the development of different economies (hunter-gatherer,

agricultural, and pastoral) and their different social and cultural characteristics.

4.

Explain how the earliest civilizations developed in challenging environments.

5.

Draw connections between the organization of labor resources in early civilizations and their

social and political structures.

6.

Assess the impact of new technologies on the social development of early civilizations.

7.

Trace the development of social and political institutions and religious beliefs in river-valley

civilizations and understand the relationship between these institutions and beliefs and their

experiences with the natural environment.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

I.

Before Civilization

A. Food Gathering and Stone Technology

1. Stone toolmaking, the first recognizable cultural activity, first appeared around 2

million years ago. The period known as the Stone Age lasted until around 4,000 years

ago. It is subdivided into the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age-to 10,000 years ago) and the

Neolithic (New Stone Age).

2. The diet of Stone Age people probably consisted more of foraged vegetable foods than

of meat. Human use of fire can be traced back to 1 to 1.5 million years ago, but

conclusive evidence of cooking (in the form of clay pots) can only be found as far back

as 12,500 years ago.

3. Researchers believe that in Ice Age society, women would have been responsible for

gathering, cooking, and childcare, while men would have been responsible for hunting.

The hunter-gatherers probably lived in fairly small groups and migrated regularly to

follow game animals and to collect seasonally ripening plants.

4. Migrating hunter-gatherer groups built huts of branches, stones, bones, skins, and

leaves as seasonal camps. Animal skins served as clothing, with the earliest evidence

of woven cloth appearing about 26,000 years ago.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

2

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

5.

B.

Hunter-gatherers probably had to spend no more than three to five hours a day on

getting food, clothing, and shelter. This left them a great deal of time for artistic

endeavors, toolmaking, and social life.

6. The foundations of what later ages called science, art, and religion also date to the

Stone Age. Gatherers learned which local plants were edible and when they ripened, as

well as which natural substances were effective for medicine, consciousness altering,

dyeing, and other purposes. Hunters learned the habits of game animals. People

experimented with techniques of using plant and animal materials for clothing, twine,

and construction. Knowledge of the environment included identifying which minerals

made good paints and which stones made good tools.

7. Cave paintings appear as early as 32,000 years ago in Europe and North Africa and

somewhat later in other parts of the world. Because many feature food animals like

wild oxen, reindeer, and horses, some scholars believe that the art recorded hunting

scenes or played a magical and religious role in hunting. Some scholars suspect that

other marks in cave paintings and on bones may represent efforts at counting or

writing.

8. Cave art suggests that Ice Age people had a complex religion. Their burial sites

indicate that they may have believed in an afterlife.

The Agricultural Revolutions

1. Agricultural revolutions—the domestication of plants and animals—were a series of

changes in food production that occurred independently in various parts of the world.

2. The first stage of the long process of domestication of plants was semicultivation, in

which people would scatter the seeds of desirable food-producing plants in places

where they would be likely to grow.

3. Early farmers used fire to clear fields of shrubs and trees and discovered that ashes

were a natural fertilizer. After the burn-off, farmers used blades and axes to keep the

land clear.

4. The transition to agriculture took place first and is best documented in the Middle East,

but the same sort of transition took place independently in other parts of the world,

including the eastern Sahara, the Nile Valley, Greece, central Europe, and along the

Danube River. Early farmers practiced swidden agriculture, changing fields

periodically as the fertility of the soil became depleted.

5. The environments in which agriculture developed dictated the choice of crops. Wheat

and barley were suited to the Mediterranean area; sorghum, millet, and teff to subSaharan Africa; yams to equatorial West Africa; rice to eastern and southern Asia; and

maize, potatoes, quinoa, and manioc to various parts of the Americas.

6. Domestication of animals proceeded at the same time as domestication of plants.

Human hunters first domesticated dogs; sheep and goats were later domesticated for

their meat, milk, and wool.

7. Like domestic plant species, varieties of domesticated animals spread from one region

to another: cattle in northern Africa and/or the Middle East, donkeys in northern

Africa, water buffalo in China, humped-back Zebu cattle in India, horses and twohumped camels in central Asia, one-humped camels in Arabia, chickens in Southeast

Asia, and pigs in several places.

8. In the Americas, domestic llamas provided meat, transport, and wool, while dogs,

guinea pigs, and turkeys provided meat. Scholars believe that these were the only

domesticated American species. However, despite the geographical isolation of the

Americas, domestic chickens first appeared before the coming of the Europeans,

presumably by way of Pacific Ocean seafarers.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

9.

C.

3

Pastoralism came to predominate in arid regions such as the Sahara. Moving large

herds of grazing livestock to new pastures and watering places throughout the year

made pastoralists almost as mobile as foragers and discouraged substantial dwellings

and the accumulation of bulky possessions.

10. Most researchers agree that humans made the transition from hunter-gatherer to

agricultural or pastoralist economies because the global warming of the Holocene

period (beginning 11,000 B.C.E.) brought with it environmental changes that reduced

the supplies of game and wild food plants.

11. The agricultural revolutions brought about a significant increase in the world’s human

population—from 10 million in 5000 B.C.E. to between 50 and 100 million by 1000

B.C.E.

Life in Neolithic Communities

1. Evidence that an ecological crisis may have triggered the transition to food production

has prompted reexamination of the assumption that farmers enjoyed a better life than

foragers. Early farmers probably had to work much harder and for much longer periods

than food gatherers. Although early farmers commanded a more reliable food supply,

their diet contained less variety and nutrition than that of foragers. Skeletons show that

Neolithic farmers were shorter on average than earlier foragers. Death from contagious

diseases ravaged farming settlements.

2. Some researchers envision violent struggles between farmers and foragers, while

others see a more peaceful transition. In most cases, farmers seem to have displaced

foragers by gradual infiltration rather than by conquest.

3. Kinship and marriage bound farming communities together. Nuclear family size

(parents and their children) may not have risen, but kinship relations traced back over

more generations brought distant cousins into a common kin network. This encouraged

the holding of land by large kinship units known as lineages or clans.

4. Some societies trace descent equally through both parents, but most give greater

importance to descent through either the mother (matrilineal societies) or the father

(patrilineal societies).

5. The early food producers appear to have worshiped ancestral and nature spirits. Their

religions centered on sacred groves, springs, and wild animals and included deities

such as the Earth Mother and the Sky God.

6. Early food-producing societies used megaliths (big stones) to construct burial

chambers and calendar circles and to aid in astronomical observations.

7. Most people in early food-producing societies lived in villages, but in some places, the

environment supported the growth of towns in which one finds more elaborate

dwellings, facilities for surplus food storage, and communities of specialized

craftspeople. The two best-known examples of the remains of Neolithic towns are at

Jericho and Çatal Hüyük. Jericho, on the west bank of the Jordan River, was a walled

town with mud-brick structures and dates back to 8000 B.C.E.

8. Çatal Hüyük, in central Anatolia, dates to 7000–5000 B.C.E. Çatal Hüyük was a center

for the trade in obsidian. Its craftspeople produced pottery, baskets, woolen cloth,

beads, and leather and wood products. There is no evidence of a dominant class or

centralized political leadership.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

4

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

9.

II.

The art of Çatal Hüyük reflects a continued fascination with hunting, but the remains

indicate that agriculture was the mainstay of the economy. The remains also indicate

that the people of Çatal Hüyük had a flourishing religion, having one religious shrine

for every two houses. Rituals involved burning dishes of grain, legumes, and meat but

not sacrificing live animals. Statues of plump female deities far outnumber statues of

male deities, suggesting that the inhabitants venerated a goddess as their principal

deity. The large number of females who were buried elaborately in shrine rooms may

have been priestesses of this cult.

10. The remains at Çatal Hüyük include decorative or ceremonial objects made of copper,

lead, silver, and gold. These metals are naturally occurring, soft, and easy to work, but

not suitable for tools or weapons, which continued to be made from stone. The

discovery of decorative and ceremonial objects of metal in graves indicates that they

became symbols of status and power.

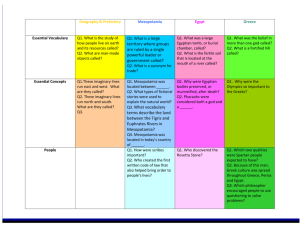

Mesopotamia

A. Settled Agriculture in an Unstable Landscape

1. Mesopotamia is the alluvial plain area alongside and between the Tigris and Euphrates

Rivers. The area is a difficult environment for agriculture because there is little rainfall,

the rivers flood at the wrong time for grain agriculture, and the rivers change course

unpredictably.

2. Although the first domestication of plants and animals around 8000 B.C.E. occurred

nearby, in the so-called Fertile Crescent region of northern Syria and southeastern

Anatolia, agriculture did not reach Mesopotamia until approximately 5000 B.C.E. The

hot, arid climate of southern Mesopotamia calls for irrigation, the artificial provision of

water to crops. Just after 3000 B.C.E., people began constructing irrigation canals to

bring water to fields farther away from the rivers.

3. By 4000 B.C.E., farmers were using ox-drawn plows and a sort of planter to cultivate

barley. Other crops and natural resources of the area included date palms, vegetables,

reeds and fish, and fallow land for grazing goats and sheep. Draft animals included

cattle and donkeys and later (second millennium B.C.E.) camels and horses. The area

has no significant wood, stone, or metal resources.

4. The earliest people of Mesopotamia and the initial creators of Mesopotamian culture

were the Sumerians, who were present at least as early as 5000 B.C.E. They created the

framework of civilization in Mesopotamia during a long period of dominance in the

third millennium B.C.E.

5. Other peoples lived in Mesopotamia as well. As early as 2900 B.C.E., personal names

recorded in inscriptions from the more northerly cities reveal a non-Sumerian Semitic

language. By 2000 B.C.E., the Sumerians were supplanted by Semitic-speaking peoples

who dominated and intermarried with the Sumerians but preserved many elements of

Sumerian culture.

B. Cities, Kings, and Trade

1. Early Mesopotamian society was a society of villages and cities linked together in a

system of mutual interdependence. Cities depended on villages to produce surplus food

to feed the nonproducing urban elite and craftspeople. In return, the cities provided the

villages with military protection, markets, and specialist-produced goods.

2. Together, a city and its agricultural hinterland formed what we call a city-state. The

Mesopotamian city-states sometimes fought with each other over resources like water

and land; at other times, city-states cooperated with each other in sharing resources and

allowing traders safe passage through their territories.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

3.

C.

5

City-states could mobilize human resources to open new agricultural land and to build

and maintain irrigation systems. Construction of irrigation systems required the

organization of large numbers of people for labor.

4. Although we know little of the political institutions of Mesopotamian city-states, we

do have written and archeological records of two centers of power: temples and

palaces. One or more temples, centrally located, housed each city-state’s deity or

deities and their associated cults (sets of religious rituals). Temples owned agricultural

lands and stored the gifts that worshipers donated. Head priests, who controlled each

shrine and managed its wealth, played prominent political and economic roles.

5. Secular leadership developed in the third millennium B.C.E. when “big men” (lugal),

who may have originally been leaders of armies, emerged as secular leaders. Although

the lugal’s position was not hereditary, it often passed from a father to a capable son.

6. The location of the temple in the city’s heart and the less prominent site of the king’s

palace symbolize the later emergence of royalty. The king’s power grew at the expense

of the priesthood, however, because the army backed him. The priests and temples

retained influence because of their wealth and religious mystique, but they gradually

became dependent on the palace. Some Mesopotamian kings claimed divinity, but this

concept did not take root. Normally the king portrayed himself as the deity’s earthly

representative.

7. By the late third millennium B.C.E., kings assumed responsibility for the upkeep and

building of temples and the proper performance of ritual. Other royal responsibilities

included maintaining city walls and defenses, extending and repairing irrigation

channels, guarding property rights, warding off foreign attacks, and establishing

justice.

8. Eventually some of the city-states became powerful enough to absorb others and thus

create larger territorial states. Two examples of this development are the Akkadian

state, founded by Sargon of Akkad around 2350 B.C.E., and the Third Dynasty of Ur

(2112–2004 B.C.E.).

9. A third territorial state was established by Hammurabi and is known to historians as

the Old Babylonian state. Hammurabi is also known for the law code associated with

his name, which provides us with a source of information about Old Babylonian law,

punishments, and society.

10. The states of Mesopotamia needed resources and obtained them not only by territorial

expansion but also through a flourishing long-distance trade. Merchants were

originally employed by temples or palaces; later, in the second millennium B.C.E.,

private merchants emerged. Trade was carried out through barter because coins did not

reach Mesopotamia until several centuries after their first appearance during the sixth

century B.C.E. Items that could not be bartered had their value calculated in relation to

fixed weights of precious metal, primarily silver, or measures of grain.

Mesopotamian Society

1. Mesopotamia had a stratified society in which kings and priests controlled much of the

wealth. The Law Code of Hammurabi identified three classes of Mesopotamian

society: (1) the free landowning class, (2) dependent farmers and artisans, and (3)

slaves. Slavery was not a fundamental part of the economy, and most slaves were

prisoners of war. Penalties prescribed in the law code depended on the class of the

offender. The lower orders received the most severe punishments.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

6

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

2.

D.

E.

Some scholars believe that the development of agriculture brought about a decline in

the status of women because men did the value-producing work of plowing,

harvesting, and digging irrigation channels. Bearing and raising children became the

primary occupation of many women, leaving them little time to acquire the specialized

skills of a scribe or artisan. Women were able to own property, control their dowry,

and engage in trade, but men monopolized political life. The rise of an urban merchant

class in the second millennium B.C.E. appears to have been accompanied by greater

emphasis on male privilege and an attendant decline in women’s status.

Gods, Priests, and Temples

1. The religion of Mesopotamia was an amalgam of Sumerian and later Semitic beliefs

and deities. Mesopotamian deities were anthropomorphic, and each city had its own

tutelary gods.

2. Nippur was regarded as a religious center because of its temple to the air god Enlil. As

with other temples, the people of Sumer considered it the god’s residence and believed

the cult statue in its interior shrine embodied his life force.

3. Humans were regarded as servants of the gods. In temples, a complex, specialized

hereditary priesthood served the gods as a servant serves a master. The temples

themselves were walled compounds containing religions and functional buildings. The

most visible part of the temple compound was the ziggurat.

4. We have little knowledge of the beliefs and religious practices of common people. The

survival of many amulets and representations of a host of demons suggests widespread

belief in magic and in the use of magic to influence the gods.

Technology and Science

1. The term technology comes from the Greek word techne, meaning “skill” or

“specialized knowledge.” It normally refers to the tools and processes by which

humans manipulate the physical world. However, many scholars also use it more

broadly for any specialized knowledge used to transform the natural environment and

human society. Thus defined, the concept of technology includes not only things like

irrigation systems but also nonmaterial specialized knowledge such as religious lore

and ceremony and writing systems.

2. Writing first appeared in Mesopotamia before 3300 B.C.E. The most plausible current

theory maintains that writing originated from a system of tokens used to keep track of

property.

3. The usual method of writing involved pressing the point of a sharpened reed into a

moist clay tablet. Because the reed made wedge-shaped impressions, the early pictures

evolved into stylized combinations of strokes and wedges, a system known as

cuneiform writing. Mastering cuneiform required years of practice. Cuneiform was

originally developed to write Sumerian but was later used to write Akkadian and other

Semitic and non-Semitic languages. Cuneiform was used to write economic, political,

legal, literary, religious, and scientific texts.

4. Other technologies developed by the Mesopotamians included irrigation, transportation

(boats, barges, and the use of donkeys), bronze metallurgy, brickmaking, and

engineering.

5. Military technology employed in Mesopotamia included paid, full-time soldiers;

horses; the horse-drawn chariot; the bow and arrow; and siege machinery.

Mesopotamians also used numbers (a base-60 system) and made advances in

mathematics and astronomy.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

7

III. Egypt

A. The Land of Egypt: “Gift of the Nile”

1. The land of Egypt is defined by the Nile River, the narrow green strip of arable land on

either side of its banks, and the fertile Nile delta area. The rest of the country is barren

desert, the unfriendly Red Land that contrasted with the Black Land, which was home

to the vast majority of the Egyptian population.

2. Egypt was traditionally divided into two areas: Upper Egypt, along the southern part of

the Nile as far south as the First Cataract, and Lower Egypt, the northern delta area.

The climate was good for agriculture, but with little or no rainfall, farmers had to

depend on the river for irrigation. Though rain rarely falls south of the delta, the river

provided water to irrigation channels that carried water out into the valley and

increased the area suitable for planting.

3. The Nile floods regularly and at the right time of year, leaving a rich and easily worked

deposit of silt, where farmers could easily plant their crops in the moist soil. Egyptian

agriculture depended upon the floods, and crops could be adversely affected if the

floods were too high or not high enough. Generally speaking, however, the floods were

regular, and this inspired the Egyptians to view the universe as an orderly and

beneficent place.

4. Egypt’s other natural resources included reeds (such as papyrus for writing), wild

animals, birds and fish, plentiful building stone and clay, and access to copper and

turquoise from the desert and gold from Nubia.

B. Divine Kingship

1. Egypt’s political organization evolved from a pattern of small states ruled by local

kings to the emergence of a large, unified Egyptian state around 3100 B.C.E. Historians

organize Egyptian history into a series of thirty dynasties falling into three longer

periods: the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, each a period of centralized political

power and brilliant cultural achievement. These three periods were divided by

Intermediate Periods of political fragmentation and chaos.

2. Kings, known as pharaohs, dominated the Egyptian state. The pharaohs were regarded

as gods on earth, whose benevolent rule ensured the welfare and prosperity of the

people. The death of a pharaoh was thought to be the beginning of his journey back to

the land of the gods. Funeral rites and proper preservation of the body were therefore

of tremendous importance.

3. Early pharaohs were buried in flat-topped rectangular tombs. Stepped pyramid tombs

appeared about 2630 B.C.E. and smooth-sided pyramids a bit later.

4. The great pyramid tombs at Giza were constructed between 2550 and 2490 B.C.E. The

great pyramids were constructed with stone tools and simple lever, pulley, and roller

technology and required substantial inputs of resources and labor. The age of the great

pyramids lasted about a century, though construction of pyramids on a smaller scale

continued on.

C. Administration and Communication

1. Egypt was governed by a central administration in the capital city through a system of

provincial and village bureaucracies. A complex bureaucracy kept detailed records of

the country’s resources. At the village, district, and central government levels,

bureaucrats kept track of land, labor, products, and people, extracting as taxes as much

as 50 percent of the annual revenues of the country. This income supported the palace,

bureaucracy, and army; paid for building and maintaining temples; and made possible

great monuments celebrating the king’s grandeur.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

8

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

2.

D.

E.

The ancient Egyptians developed two writing systems: hieroglyphics and a cursive

script. Egyptians wrote on papyrus and used writing for religious and secular literature

as well as for recordkeeping.

3. Tensions between the centralizing power of the monarchy and the decentralizing

tendencies of the bureaucracy are a constant feature of Egyptian political history. The

breakdown of centralized power in the late Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period

was signified by the shift of officials’ tombs from the vicinity of the royal tomb to the

home districts where they spent much of their time and exercised power, and by

inheritance of administrative posts.

4. Egypt was more rural than Mesopotamia. It did have cities, but since they have not

been excavated, we know little about urban life in Egypt.

5. Egypt regarded all foreigners as enemies, but its desert nomad neighbors posed no

serious military threat. Egypt was generally more interested in acquiring resources than

in acquiring territory; resources could often be acquired through trade.

6. Egypt traded directly with the Levant coast (modern Israel, Lebanon, and Syria) and

Nubia and indirectly with the land of Punt (probably part of modern Somalia). Items of

trade included exports of papyrus, grain, and gold and imports of incense, Nubian gold,

Lebanese cedar, and tropical African ivory, ebony, and animals.

The People of Egypt

1. Ancient Egypt had a population of about 1 to 1.5 million physically heterogeneous

people, some dark-skinned, and some lighter-skinned. The people were divided into

several social strata: (1) the king and high-ranking officials; (2) lower-level officials,

local leaders, priests and other professionals, artisans, well-off farmers; and (3)

peasants. The majority of the people were peasants.

2. Peasants lived in rural villages, cultivated the soil, maintained irrigation channels, and

were responsible for paying taxes and providing labor service. Slavery existed on a

limited scale and was of little economic significance. Prisoners of war, condemned

criminals, and debtors could be found on country estates or in the households of the

king and wealthy families.

3. Paintings indicate that women were subordinate to men and engaged in domestic

activities. Egyptian women could own property, inherit from their parents, and will

their property to whomever they wished, and they retained rights over their own dowry

after divorce. Evidence suggests that women in ancient Egypt enjoyed greater respect

and more legal rights and social freedom than women in Mesopotamia.

Belief and Knowledge

1. Egyptian religious beliefs were based on a cyclical view of nature. Two of the most

significant gods, the sun-god Re and Osiris, god of the Underworld—who was killed,

dismembered, and then restored to life—represented renewal and life after death.

2. The king, represented as Horus and as the son of Re, served as the chief priest. The

supreme god of the Egyptian pantheon was generally the god of the city that was

serving as the capital.

3. Egyptian rulers zealously built new temples, refurbished old ones, and made lavish

gifts to the gods. Thus, much of the country’s wealth went for religious purposes in the

ceaseless effort to win the gods’ favor, maintain the continuity of divine kingship, and

ensure the renewal of life-giving forces.

4. We know little about popular religious beliefs. What we do know indicates that the

Egyptians generally believed in magic and in an afterlife. Concern with the afterlife

inspired Egyptians to mummify the bodies of the dead before entombing them.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

5.

9

Tombs contain pictures and samples of food and other necessities and thus are a

valuable source of information about daily life in Egypt. Tombs were usually built at

the edge of the desert to avoid wasting arable land. The amount and quality of tomb

goods and the form of the tombs themselves reflect the wealth and social status of the

deceased.

6. The ancient Egyptians acquired much advanced knowledge and technology.

Knowledge of chemistry and anatomy was gained in the process of mummification.

Other areas of scientific and technological advance included mathematics, astronomy,

calendar making, irrigation, engineering and architecture, and transportation

technology.

IV. The Indus Valley Civilization

A. Natural Environment

1. The central part of the Indus Valley area is the Sind region of modern Pakistan.

Adjacent related areas included the Hakra River (now dried up), the Punjab, Delhi, and

the Indus delta region.

2. The Indus carries a lot of silt and floods regularly twice a year, which allowed farmers

in the Indus Valley and related areas to produce two crops a year despite the region’s

sparse rainfall.

B. Material Culture

1. The Indus Valley civilization flourished from 2600 to 1900 B.C.E. The two largest and

best-known urban sites are those at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. Unfortunately, the

high water table at these sites makes excavation of the earliest levels of settlement

nearly impossible.

2. Scholars once believed that the people who created this civilization spoke Dravidian

languages related to those spoken today in southern India. The writing system of the

Indus Valley people contained more than four hundred signs to represent syllables and

words. Archaeologists have recovered thousands of inscribed seal stones and copper

tablets. The inscriptions are so brief, however, that no one has yet deciphered them,

though some scholars believe they represent an early Dravidian language.

3. The two major urban centers of the Indus Valley were Harappa (3½ miles in

circumference, population about 35,000) and Mohenjo-daro (several times larger).

Both settlements are surrounded by brick walls, have streets laid out in a rectangular

grid pattern, and are supplied with covered drainage systems to carry away waste.

There are remains of something like a citadel that may have been a center of authority,

structures that may have been storehouses for grain, and barracks that may have been

for artisans.

4. Both urban centers may have controlled the surrounding farmland. Harappa was

located on the frontier between agricultural land and pastoral economies and may have

been a nexus of trade in copper, tin, and precious stones from the northwest.

5. The Indus Valley civilization is characterized by a high degree of standardization of

styles and shapes between the smaller settlements and the large cities. Some scholars

have sought to explain this uniformity by hypothesizing the existence of an

authoritarian central government, while others argue that it may have been a result of

extensive trade within the region.

6. The people of the Indus Valley had better access to metal than did the Egyptians and

the Mesopotamians. Thus, the Indus Valley artisans used metal to create utilitarian

goods as well as luxury items.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

10

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

7.

V.

Technological achievements of the Indus Valley civilization included extensive

irrigation systems, the potter’s wheel, kiln-baked bricks, and a sophisticated bronze

metallurgy. The people of the Indus Valley carried out an extensive trade with the

northwestern mountain areas, Iran and Afghanistan, western India, and even

Mesopotamia.

8. We know little about the political, social, economic, and religious structures of the

Indus Valley, nor do we know what historical circumstances led to the development of

a sophisticated urban civilization. Part of the problem is that, although they had a

writing system, modern scholars are unable to decipher it.

C. Transformation of the Indus Valley Civilization

1. Scholars formerly believed that the Indus Valley cities were abandoned sometime after

1900 B.C.E. because of an invasion. Further evidence has convinced researchers that

the decline of the Indus Valley civilizations was due to a breakdown caused by natural

disasters and ecological change.

2. Ecological changes that probably led to a decline in agricultural production and the

eventual collapse of the Indus Valley civilizations include the drying up of the Hakra

River, salinization, and erosion. When urban centers collapsed, so did the way of life

of the elite, but the peasants probably adapted and survived.

Comparative Perspectives

A. Political and Economic Comparisons

1. Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley civilizations all developed along river

systems where they were assured an adequate water supply for agriculture.

2. They all developed political structures for organization of labor to provide irrigation

systems.

3. Kingship developed as the political leadership system of both Egypt and Mesopotamia,

though Egypt’s kings were believed to be divine in origin, while Mesopotamia’s rulers

were not.

B. Religious and Cultural Comparisons

1. The predictable flooding of the Nile translated into a relatively optimistic outlook on

the afterlife for Egyptians.

2. In contrast, the unpredictable and violent flooding of the Tigris-Euphrates Basin gave

Mesopotamians a more fearful expectation of their afterlife.

3. Newcomers to both Egypt and Mesopotamia assimilated easily into the established

civilizations.

4. Egyptian women appear to have enjoyed more equality in society than did

Mesopotamian women.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1.

What effects did the agricultural revolutions have on Neolithic societies?

2.

What were women’s roles in the first 4 million years of human history? What evidence can we

find that might give us some indications of what women’s roles may have been? Does the

evidence indicate how women’s roles may have changed over time? How and why might such

change have occurred?

3.

What evidence do you see here of interaction between these civilizations and other peoples

(including interaction among the three civilizations themselves)? How important do you think that

interaction with other peoples was for the development of these three civilizations?

4.

What demands arose for these civilizations that led to their technological advancements?

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

11

5.

What factors might explain the rise and decline of civilizations in general and of these particular

civilizations?

6.

How do the religious beliefs and world-views in Mesopotamia and Egypt reflect the relationships

between the environment and the people of these civilizations?

7.

What is the connection between knowledge and power? How did writing play into this

relationship?

LECTURE TOPICS

1.

The Agricultural Revolutions

Sources:

2.

a.

Cohen, Mark Nathan. The Food Crisis in Prehistory: Overpopulation and the Origins of

Agriculture. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1977.

b.

Johnson, Allen W., and Timothy Earle. The Evolution of Human Societies: From Foraging

Group to Agrarian State. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1987.

c.

Ponting, Clive. A Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great

Civilizations. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

d.

Wenke, Robert J. Patterns in Prehistory: Humankind’s First Three Million Years. 4th ed.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Megaliths and Their Meanings

Sources:

3.

a.

Gibson, Alex, and Derek Simpson, ed. Prehistoric Ritual and Religion: Essays in Honour of

Aubrey Burl. Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton, 1998.

b.

MacKie, Euan Wallace. Science and Society in Prehistoric Britain. New York: St. Martin’s

Press, 1977.

c.

Mohen, Jean-Pierre. The World of Megaliths. New York: Facts on File, 1990.

d.

Pearson, M. Parker. “Stonehenge for the Ancestors: The Stones Pass on the Message,”

Antiquity 72 (June 1998).

Çatal Hüyük: A Neolithic Town

Sources:

4.

a.

Eichman, William Carl. “Çatal Hüyük: The Temple City of Prehistoric Anatolia: The Oldest

Known City and Its Religious Philosophy.” Gnosis 15 (Spring 1990).

b.

Mellaart, James. Çatal Hüyük: A Neolithic Town in Anatolia. London: Thames and Hudson,

1967.

c.

Todd, Ian A. Çatal Hüyük in Perspective. Menlo Park: Calif.: Cummings Publishing Co.,

1976.

Women in Prehistoric Times

Sources:

a.

Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years. New York: W.W.

Norton and Co., 1994.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

12

5.

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

b.

Ehrenberg, Margaret. Women in Prehistory. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

c.

Gero, Joan M., and Margaret W. Conkey, eds. Engendering Archaeology: Women and

Prehistory. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1991.

The World of Gilgamesh

Sources:

6.

a.

Postgate, J. N. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London:

Routledge, 1994.

b.

Roaf, Michael. Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. New York:

Checkmark Books, 1990.

c.

Sandars, N. K. trans. The Epic of Gilgamesh. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1972.

Religion in the Ancient World

Sources:

7.

a.

Hornung, Erik. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University

Press, 1999.

b.

Jacobson, T. Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1976.

c.

Quirke, Stephen. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Dover Publishers, 1990.

The Great Pyramids of Giza

Sources:

8.

a.

Edwards, I. E. S. The Pyramids of Egypt. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1978.

b.

Hawass, Zahi, and Mark Lehner. “Builders of the Pyramids.”Archaeology 50:1 (Jan. 1997).

c.

O’Connor, David. “Boat Graves and Pyramid Origins: New Discoveries at Abydos, Egypt.”

Expedition 33:3 (1991).

d.

Smith, William Stevenson. The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt. 3rd ed. New Haven,

Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998.

Indus Valley Civilizations

Sources:

9.

a.

Kenoyer, Jonathan M. Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Karachi, India: Oxford

University Press, 1998.

b.

Possehl, Gregory L., ed. Ancient Cities of the Indus. New Delhi, India: Oxford University

Press, 1979.

c.

Possehl, Gregory L. Harappan Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. New Delhi, India:

Oxford University Press, 1982.

Trade and Trade Networks in the Early Civilizations

Sources:

a.

Cameron, Rondo E. A Concise Economic History of the World: From Paleolithic Times to

the Present. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

13

b.

Curtin, Philip D. Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1984. Chapter 4, “Ancient Trade” discusses Mesopotamian, Assyrian, and Egyptian

trade and includes references to a number of useful articles.

c.

Shereen, Ratnagar. Encounters: The Westerly Trade of the Harappan Civilization. Delhi:

Oxford University Press, 1981.

10. Daily Life in River-Valley Civilizations

Sources:

a.

Collon, Dominique. First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1988.

b.

Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Karachi, India:

Oxford University Press, 1998.

c.

Postgate, J. N. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London:

Routledge, 1994.

d.

Romer, John. People of the Nile: Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt. New York: Crown, 1982.

e.

Strouhal, Eugen. Life of the Ancient Egyptians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

PAPER TOPICS

1.

Choose a particular part of the world and research the question of when and how agriculture

developed in that area.

2.

Compare the transition from hunting and gathering to food production in the Eastern and Western

Hemispheres.

3.

Compare the role of trade in the Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Indus civilizations.

4.

Research the development and applications of bronze metallurgy in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the

Indus Valley.

5.

Write a paper expressing and justifying your agreement or disagreement with the following

statement: “Despite their different environmental conditions, Egypt and Mesopotamia developed

very similar institutions of government.”

6.

What does the study of the Great Pyramids tell us about the Egyptian technology of the time?

7.

Compare women’s roles in the different river-valley societies.

INTERNET RESOURCES

The following Internet sites contain written and visual material appropriate for use with this chapter. A

more extensive and continually updated list of Internet resources can be found on The Earth and Its

Peoples website.

Paleolithic

http://www.paleolithic.com/

The Cave of Lascaux

http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/arcnat/lascaux/en/

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

14

Chapter 1: From the Origins of Agriculture to the First River-Valley Civilizations, 8000–1500 B.C.E.

The State Heritage Museum—Neolithic Art

http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/html_En/03/hm3_2_2.html

Çatal Hüyük—The Mysteries of Catal Hüyük

http://www.smm.org/catal/

The Oriental Institute Museum of the University of Chicago

http://oi.uchicago.edu/museum/

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York—Works of Art: Ancient Near Eastern Art

http://www.metmuseum.org/Works_of_Art/department.asp?dep=3

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York—Works of Art: Egyptian Art

http://www.metmuseum.org/Works_of_Art/department.asp?dep=10

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—Explore Ancient Egypt

http://www.mfa.org/egypt/explore_anicent_egypt

The University of Memphis Institute of Egyptian Art & Archaeology

http://academic.memphis.edu/egypt/artifact.html

ETANA (Electronic Tools and Ancient Near Eastern Archives)—ABZU (A guide to information

related to the study of the Ancient Near East on the Web)

http://www.etana.org/abzu/

NOVA Online—Mysteries of the Nile: Explore Ancient Egypt

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/egypt

Harappa.com

http://www.harappa.com/index.html

University of Alabama at Birmingham—Images from History

http://www.hp.uab.edu/image_archive/noframes.html

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.