Wicked Problems, Hybrid Organisations, and `Clumsy Institutions` at

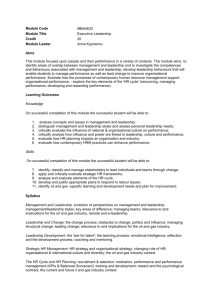

advertisement