[2] Cf. Gábor Bezeczky, “1969: Befejezetlen történet: a magyar

advertisement

![[2] Cf. Gábor Bezeczky, “1969: Befejezetlen történet: a magyar](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007406878_1-196f18e76b4e2a7b0312eeb42876931c-768x994.png)

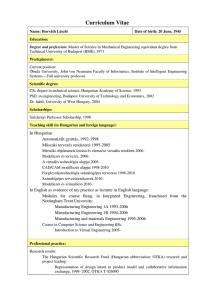

1 The Interpretation of Classical Literature in the 1960s and 1970s Péter Hajdu If one looks at the amount or proportion of papers that discussed literary topics in the journal of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on classical studies, called Antik Tanulmányok (Fifures 1 and 2), they may have the impression that literature became the most important field of research in the second half of the 1970s. literary papers in AT 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 19 54 19 (1 56 4) 19 (1 58 4) 19 (1 60 2) 19 (1 62 2) 19 (1 64 6) 19 (1 66 7) 19 (1 68 1) 19 (1 70 1) 19 (1 72 2) 19 (1 74 6) 19 (1 76 5) 19 (1 78 2) 19 (1 80 3) 19 (1 82 8) 19 (1 19 84 1) 87 (1 /8 7) 8 (1 3) Series1 Figure 1 2 Lirterary papers' percentage 1954-1989 60 50 % 40 30 Series1 20 10 0 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 year Figure 21 The aspect of quantity suggests that the prestige of the hard core philological work, i.e., working with classical texts, was relatively high in the scholarly community that time, but if we look on the achievement of that generation from the viewpoint of literary studies, the lack of innovative force is rather obvious. Of course I will not use harsh evaluative terms to describe the output, first of all because false generalizations would be unfair. What is interesting is the development (or decline) within the Hungarian scholarly community. In the 1930s Hungarian publications on classical literature (first of all by those associated with the circle of Károly Kerényi) were in harmony with recent international trends in literary studies, and were able to exert an influence on or elicit response from the wider society. In the 1970s and 1980s the theoretical and methodological foundation of the papers tends to be obsolete, the innovative force apparently disappeared, and this contrast is not caused by ideological censorship alone. Hardly any signs of ideological bias can be detected in the late socialist period issues of 1 The AT published 34 volumes in 36 years. The last two volumes belonged to double years (1986/87 and 1988/89, respectively). The apparent discrepancy of volumes and years is the result of this situation. 3 Antik Tanulmányok. It is rather the lack of ideological bias, which is striking. In the years when the wider Hungarian literary studies community experienced fierce discussions about structuralism (or structuralism vs. Marxism),2 classical scholars did not seem to have heard of structuralism at all. How could have this community lost their contact to the wider context of scholarship? Once again: I am speaking of a community, not of individuals. And what is also important: one cannot see a rupture or a gap in the scholarly tradition. In spite of the various historical confusions the tradition seemed more or less continuous; one generation educated the next. The three possible causes of the change I would like to discuss here are as follows: 1. The obligatory Marxism had devastating effect on literary studies in the 1950s, which exerted a long-term effect on the generations which were being educated that time. 2. Scholars found different loopholes to escape the obligation of being overtly Marxists; such strategies failed to be innovative in a wider context. 3. The selection of the next generation seems usually have been influenced by (supposedly political) factors that were not really adequate. The memorable ideological conflict of the 30s on the mission and most desirable strategy of classical scholarship in Hungary, which is usually described as the “Kerényi vs. Moravcsik debate”, although a rather significant number of scholars were involved, 3 ended with a seemingly double result. On the one hand, the cause of the “classical philology of national interest”, which emphasized the importance of the local embeddedness of research and wanted to focus on Byzantine studies and provincial archeology, triumphed in academic life, all the important positions were occupied by its representants in the 30s. On the other hand, the talented youth wanted to be Kerényi’s disciples, and the next generation actually was educated by his circle. All the important positions in the committees of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, university departments and in editorial committees of scholarly journals were occupied by Kerényi’s disciples after WWII, with the important exemption of Gyula Moravcsik himself, who remained the “big boss”. However, the impression of a long-term win of Kerényi’s side is false. In spite of the explicit declarations, it was not only the thematic Cf. Gábor Bezeczky, “1969: Befejezetlen történet: a magyar strukturalizmus rövid tündöklése.” János György Szilágyi: “Trencsényi-Waldapfel Imre” in Antik Tanulmányok 17, 1970, 150-153. In this strange obituary not less than 7 pages (150-157) of the 19 are occupied by a eulogy of Károly Kerényi. 2 3 4 aspect at stake (“What should we research?”), but also methods of approach. The “national” classical philology was founded on positivism; its representatives regarded scholarship as a cumulative process, while Kerényi's circle (in accordance with the recent European trends of Geistesgeschichte) was interested rather in the interpretation of what has already been found. And positivism gained a sort of hegemony during communism.4 This development also had various reasons, to be sure. One of them is the communist belief in science, positive knowledge or a truth that cannot be relativized. An interest in literaryness could easily be condemned as bourgeois aestheticism, and the only acceptable way of interpretation in communist context, which described the literary work as representation of social or economic facts, had devastating effect on literary studies. It was not necessarily so in other fields of humanities. The different levels Imre TrencsényiWaldapfel (1908-1970, a leading figure in the 50s) achieved in history of religion and literary studies, respectively, might offer a telling example. His papers on religion tend to be brilliant despite the numerous quotations from Engels that sometimes play important role in the way of argumentation. When he analyzes a piece of literature, however, he makes of it a manifesto on topical social or political issues. Hardcore and vulgar Marxist interpretations are too thin, the analyses tend to be rather primitive, when literature is involved. Religion is a different challenge. Here Marxism at least implies a demand of interpretation from a different angle, which seems to enrich the meaning of the given phenomena. I do not want to say that Marxism is more adequate in the analysis of religion as a social practice than in the analysis of literature as representation of social practices. I rather think that in the contemporary context of religious and literary studies, respectively, Marxist methods were more innovative when applied to religion. And we can come to a similar conclusion if we take the effect on the society into consideration, or at least the possibility of convincing those in power that scholarly activity can have such an effect. I have the suspicion that working with ancient classics was regarded as a symptom of bourgeois decadence by socialist leaders, while religion was always a hot topic. The evidence of Imre Trencsényi-Waldapfel's correspondence shows that he spent a lot of time in committees responsible for anti-religious propaganda. We can say, 4 Cf. László Török, “Magyar ókortörténet a 21. század elején” in Antik Tanulmányok 52, 2008, 127-135. 5 religious studies offered better career opportunities during the communist period, and the required Marxist method probably offered more intensive intellectual inspiration. It is interesting that the Hungarian scholars, who took over the central academic positions in the 50s, had a reliable knowledge of Russian (many of them had learned the language as captives in WWII), and therefore they could have early access to those highly innovative Russian literary theories that were to fertilize western thinking in the 60s. Even if they read the works of Russian formalists, no influence can be detected. The real problem with this dull synthesis of vulgar Marxism and positivism is its long-term effect. Literary papers published in the Hungary of the 1950s were not of top quality, first of all due to the strong ideological bias, but it is OK, since it was a difficult period. Later, however, there came a generation educated in that context. Some major scholars in the 50s, like Imre Trencsényi-Waldapfel, were writing bad papers more or less intentionally. They were well educated people with wide intellectual horizon, but they willingly, enthusiastically or just in order to survive adapted to party requirements. But many members of the generation taught by them in a time when they did not want or did not dare to show their whole intellectual capacity became defenseless against the official literary theory. Not all of them, to be sure. But a tendency seems visible, and it also seems connected with human resources policy. Communists had an inclination to prefer first generation intellectuals as a part of their policy of elite shift. Those young people who came to the university without any intellectual equipment provided by the family tended to inherit the flat positivism of the 50s, which with the disappearance of the overt vulgar Marxist stupidities became, if less shocking, but even duller. The career of Róbert Falus (1925-1983) can be a telling example, which can also exemplify the most evident strategy of adaptation to communism, namely being a communist. He was the son of a bookbinder, and only communism gave him a chance to attend the university. He became a Party member and a student at the same time. His style, when he was writing literary history, was rather similar to committed journalism. (He was also the columnist of a newspaper.) His most prestigious work is a full length history of ancient literature; he published a History of Greek literature in 1964, then a History of Roman literature in 1970, which were unified in 1976 as History of Ancient 6 Literatures.5 It is a continuous narrative, easy to read, which focuses on the authors' life stories, personal deeds and emotions. Evaluation is always politically founded, but the formulation has a certain air of party journalism from the 50s. The fast sentences, which tend to contain many adjectives, have an inclination for lower stylistic registers, in order to simulate eruptions of plebeian emotions. Let me quote an example, when Falus describes Catullan love: “Prudish behavior of others never influenced Catullus. In the contrary: it incited him to eject his happiness of kisses and hogs into the face of old, impotent asses and insensitive, out-burned gigolos.”6 Falus could have been a good satirical writer, but as a scholar he was poorly equipped. That he was able to be the head of the department for Greek in the most important Hungarian university without a reliable knowledge of Greek (as witnesses told me) or Latin language (as evidence shows) suggests that he rather had a political career. The case of István Károly Horváth (1931-1966) may be more interesting, since his figure lives in the memory as that of the most talented young man who died a tragic early death. According to a half-funny proverb Hungarian intellectuals had to choose between two life strategies after 1956. One of them was alcoholism, while the other was unviable. Since Horváth's death was almost direct consequence of his alcoholism, the legendary narrative of his lot can be regarded as expressing the Hungarian condition. In this context his self-destroying behavior can be interpreted as an almost heroic act of resistance by a young, romantic genius. Actually his career seems to have been rather easy. In 1954, right after finishing the university, he received a full length scholarship by the Academy (while Falus had only a shortened one), and he got the title of a “candidate” with flying colors. He was sent to be a university teacher in Szeged (and not in the capital), but when he was 35 years old, he was invited to be a member of the editorial committee of Antik Tanulmányok in 1965, which was an important position.7 This successful academic 5 A görög irodalom története. Budapest: Gondolat, 1964; A római irodalom története. Budapest: Gondolat, 1970; Az antik világ irodalmai. Budapest: Gondolat, 1976. 6 Falus 1976, 429. 7 The members of the editorial committee were as follows: János Harmatta, István Károly Horváth, Egon Maróti, Csaba Töttössy, Imre Trencsényi-Waldapfel. Only those in italics were members continuously from 7 career, of course, does not mean that he had no reason to be depressed or anything to be cured with alcohol. Despite the shortness of his life, his scholarly output is remarkable, and much more then a promise. We can really speak of his achievement. He was deeply interested in comic and satirical genres, which is evidenced not only by his important paper on the social prestige of comic genres in Roman context called “Musa severa ― Musa ludens”8 or by the short list of the authors he wrote about (namely Catullus, Ovid, Petronius, Persius and Juvenal), but also by the legendary anecdote that he tried to collect the various manuscripts of Indecent Toldi, the pornographic (and highly imaginative) parody of the most canonical Hungarian epic poem, Toldi by János Arany. He is said to have been preparing a critical edition.9 In order to adapt this interest to the ideological requirements of the communist system Horváth focused on two minor Marxist issues, namely popular culture and realism. Let me start with the latter. Realism was a much discussed topic in Soviet literary scholarship in the 1950s, but by the time when Horváth started to write about ancient realism, that school, which wanted to interpret the history of world literature as a struggle between realism and anti-realism (in parallel with idea of the history of philosophy as struggle between idealism and materialism), has been marginalized (or banned).10 Of course, not everybody knew it in Hungary, but the Institute of Literary Studies of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences published a booklet in 1959, called “The Conclusions of the Soviet Discussion on Realism”, which made it clear that the primitive vulgar Marxist attitude of evaluation that realism is good, non-realism is bad was passé in the wider communist context. Horváth was not up-to-date when he thought that proving his favorite authors were realists was enough to legitimize his scholarly activity as Marxism. Or he was very much up-to-date. In 1965 there was a change in the Hungarian cultural politics, and the the beginning. Two founding editors (István Borzsák and János György Szilágyi) were excluded from the committee in 1958 as a result of a purge. 8 In Antik Tanulmányok 3, 1956, 92–104. 9 See Lóránt Czigány, “A szexuális őserő eposza” in Pajzán Toldi, ed. Lóránt Czigány, Budapest: Kortárs, 1997. 10 A szovjet realizmus vita tanulságai. Budapest: MTA Irodalomtudományi Intézet, 1959, 16. Lajos Nyírő, who held a long keynote speech, which was published in that booklet, had advertised this developments two years earlier in a journal that had the mission of informing the Hungarian public of what was happening in world literature. (“A realizmus kérdései a szovjet folyóiratokban” in Irodalmi Figyelő 3, 1957.) 8 influence of those who stuck to a “Stalinist concept” of “eternal realism” grew. 11 Horváth concept might have pleased the most powerful ideology makers in Hungary while being obsolete not even in international, but also in a wider communist context. And it not only makes his theory of realism seem a product of provincialism in retrospect, but also connects his name with such people like István Király and Pál Pándi, whose memory is rather uncomfortable nowadays. The other central notion, namely popular literature seems more interesting. On the one hand, it was a good idea to connect comic literature and lower stylistic registers to the literary production of the people, since ideologically it was evident that what the people were doing was good. And the most recent evaluation of Horváth’s achievement came to the conclusion that his sophisticated analyses of Catullus’ lyric poetry were quite in harmony with the contemporary international context.12 On the other hand, I cannot help feeling that Horváth missed a really great opportunity here. An interest in the culture of the people and in the comic comical genres resulted in the highly innovative theory of popular laugh culture and carnival for Mikhail Bakhtin. Of course it would be unfair to condemn Horváth, because his approach was not as innovative as that of Bakhtin, one of the most creative theory makers of the century; and especially in the late 50s and early 60s it was not so easy to read Bakhtin. His book on Rabelais with the carnival theory was written in 1941, but it remained unpublished until 1965. Only a circle in the Gorky Institute in Moscow knew and admired the dissertation previously. However, that theory was in some detail already designed in Bakhtin’s book on Dostoevsky in 1929, although its second edition had not been appear before 1963.13 Therefore Horváth had hardly any chance to read Bakhtin, and he probably did not know that he should have to do so, which allows us to ask about the responsibility of those who had taught him at the university (Trencsényi-Waldapfel and Borzsák, first of all). Nevertheless the impression of a missed opportunity can be had, because a very innovative theoretical framework “‘Túlélésünk sikertörténetében saját sorsomra ismerek’ Beszélgetés Csetri Lajos irodalomtörténésszel” in Tiszatáj 54. 2000, 121. 12 Ábel Tamás, “A lírától a ‘líráig’: Horváth István Károly Catullus-tanulmányainak leporolása” in Az olvasás rejtekútjai: Műfajiság, kulturális emlékezet és medialitás a 20. századi magyar irodalomtudományban, eds. Tibor Bónus, Zoltán Kulcsár-Szabó & Attila Simon, Budapest: Ráció, 2007, 232-249. 13 For details of accessibility of Bakhtin’s work see Michael Holquist, Dialogism. Routledge: London, 2002, 1-14. 11 9 became internationally accessible more or less at the same time when Horváth was working on a seemingly similar problem. And it is this context that makes the lack of innovative force remarkable. Another person that started a career in classical philology in the 50s wanted creativity so basically that she hardly published more than 3 papers in her entire life; luckily, I must add. As the report of a meeting of Committee for Classical Philology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences from 16. January 1953 says, “Aspirant Mrs. Berényi, Mária Révész has received an admonition letter of very harsh tone about her achievement from the department secretariat of the I. Class of the Academy.” The Committee decided that Imre Trencsényi-Waldapfel will back up her against Academy authorities.14 The authority to be confronted actually was the secretary of the I. Class, namely Tibor Klaniczay, whose sense for quality was legendary in the later phases of his administrative and organizing career. As later developments show, Klaniczay was evidently right in the evaluation of Révész’s achievement, but Trencsényi-Waldapfel won. She remained in the university department for ages. The last letter by TrencsényiWaldapfel, which is served in the manuscript collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences was sent to the dean of the Faculty for Humanities of the Budapest University, suggesting the Mária Révész should receive some premium for teachers’ day, since she was a great help to the head of the department in many administrative issues.15 Finally I will quote single sentences of three papers from the 1979 issue of Antik Tanulmányok. Each paper discusses literary subjects, but they are written by scholars belonging to different generations. Let start with the oldest one, educated in the 30s, then head of Latin department in Budapest. He wrote that Horace’s “epistle to Augustus has received a lot of diverse interpretations, or rather a lot of lack of understanding.”16 We can see the strong belief in fixed meaning, and a doubtless confidence, which was characteristic of the 19th century positivism, that the narrator of the paper finally will be able to tell the final truth and to brush aside all the misunderstandings of previous centuries. Another scholar, a generation younger, educated in 50s, discussed a general 14 MTA Levéltár, I. Nyelv- és irodalomtudományok osztálya iratai 59. Klasszika-filológiai Bizottság 195367; 8. 1953. jan. 16. jegyzőkönyv. 15 14. May, 1970. MJ 4327/1-67 16 István Borzsák: “Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit” in Antik Tanulmányok 26, 1979. 49 10 shift in the interpretation and evaluation of Euripides’ Alcestis, and he wrote: “It might be interesting to analyze this shift of the play’s interpretation in the general context of intellectual history.”17 This approach is completely different. It presupposes that interpretation or meaning, at least partly, depends on the interpreter and their cultural background. The obsolete positivism is absent; this attitude towards literature is fresh and up-to-date. However, as we saw, only a small minority of those educated in the 50s was able to develop such theoretical framework and achieve such quality. The third paper I would like to quote analyzed Horace’s Epodus 16, and it was written by someone who studied at the university in the 60s. “The historical overview is muddled in a sophisticated way in order to express the poet’s unstrung state of mind.” 18 The whole poem is called “a cry of desperation by the young poet”, and what is rather funny, river Euphrates is called a watershed. The latter suggests some weakness in general education, while the former formulations suggest really outdated ideas about literature, as it was direct expression of the authors’ mental processes or psyche. Generations, of course, live together, and they simultaneously contribute to a given scholarly context. A simple narrative of decline cannot be justified, and one of the conclusions, which can be drawn, is that anyone had the chance to acquire a relatively wide intellectual or theoretical horizon. Those first generation intellectuals, however, who had to rely on the communist university education more or less exclusively, were seriously handicapped in this respect. 17 18 Zsigmond Ritoók: “Euripidés Alkéstisa: vígjáték vagy tragédia” Antik Tanulmányok 26, 1979. 2. János Bollók: “A XVI. epódos és a római sibyllinumok” Antik Tanulmányok 26, 1979. 57.