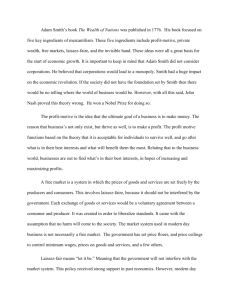

Excerpt from The Second Coming of Adam Smith

advertisement

Excerpt from The Second Coming of Adam Smith Todd C. Buchholz We Can All Be Rich How Self-Interest, The Invisible Hand, and the Ideas of an eccentric Scotsman Brought Economic Prosperity to Much of the World From Radical Academic to Conservative Icon From the middle Ages until roughly the time of Columbus, theologians had dominated European intellectual thought. Church elders interpreted natural phenomena in accordance with religious doctrine. But in [the 1600s] more people began following the bold paths of Francis Bacon and Nicolaus Copernicus in searching for rational explanations for natural events. Eventually, scientists emerged independent of ruling churches applying the “scientific method” for laws of nature regardless of controversial conclusions. Toward the end of his Discourse on Method (1637) Rene Descartes foreshadowed the explosion of thought in the eighteenth century by arguing that through practical science men can be the “masters and possessors of nature.” Adam Smith was born into this movement. Like Galileo and Newton, Smith sought out cause-and-effect relationships. But instead of focusing his view on planets, he focused on people. Born in 1723, Smith grew up with his mother in Kircaldy, a small port located across the Firth of Forth from Edinburgh, Scotland. His father, a comptroller of customs, had died months before his birth. Smith himself never married. He had a large nose, bulging eyes, a protuding lower lip, a nervous twitch, and a speech impediment. Smith once acknowledged his unusual features, saying, “I am a beau in nothing but my books.” A good student, Smith entered the University of Glasgow at the age of fourteen, and later accepted a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford. Like many college students, Smith complained about his teachers, “In the university of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching.” More important, Smith lashed out at academic censorship and complained to friends that college officials had confiscated his copy of David Hume’s heralded Treatise on Human Nature. Although he was permitted to read all of the ancient Greek and Latin classics, Smith was forbidden from reading one of the most potent works of his own time. Despite academic restrictions, Smith was so influenced by David Hume’s skepticism (A Theory of Human is subtitled, “An Attempt to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects.”) that he refused to continue preparing for the clergy. Instead he returned to Kircaldy, where he later delivered popular public lectures on rhetoric and law. In 1748, Smith returned to the University of Glasgow to teach logic. The next year he filled the chair in moral philosophy vacated by his former teacher, Frances Hutcheson. A “campus radical,” Hutcheson had stirred administrators by refusing to lecture in Latin. [School officials] then prosecuted him for spreading the following “false and dangerous” doctrines: 1. The standard of moral good is promotion of happiness to others. 2. It is possible to know good and evil without knowing God. (It is interesting to note that Smith’s ideas are usually associated today with conservative politics, yet because his intellectual roots were rather radical, some contemporary conservatives feel a bit uneasy about Smith. Others, however, seek desperately to place his capitalist theories on the same altar as God, apple pie, and democracy.) The Birth of Economics As a Discipline Smith never taught a course in economics. In fact, Smith never took a course in economics. Nobody did. Until the nineteenth century, academics considered economics a branch of philosophy...Nonetheless, Smith squeezed his preliminary thoughts on economics into lectures on jurisprudence. The following notes taken by [Smith’s] student, point to the genesis of his key analysis of labor later elaborated in The Wealth of Nations: Division of labor is the great cause of the increase of public opulence, which is always proportioned to the industry of the people, and not to the quantity of gold and silver, as it is foolishly imagined. Even before Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations, he gained fame in 1759 with his book on ethical behavior, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. As sales burgeoned, he became known as “Smith the philosopher.” A Theory of Moral Sentiments followed in the Enlightenment tradition. Just as scientists searched for the origin of the solar system, Smith searched for the origin of moral approval and disapproval. How can a man who is chiefly interested in himself make moral judgments that satisfy other people? After all, each person stands at the center of his own system, just as the sun stands at the center of the planets. Does the sun care what the smaller planets think? Smith struggled with this paradox, asking himself why, if people are selfish, each town does not resemble the vicious state of nature the political theorist Thomas Hobbes portrayed in Leviathan, Hobbes argued that man’s life is “solitary, nasty, brutish, and short” until governments emerge. Finally, Smith concocted a clever answer. When people confront moral choices, he said, they imagine an “impartial spectator” who carefully considers and advises them. Instead of simply following their self-interest, they take the imaginary observer’s advice. In this way, people decide on the basis of sympathy, not selfishness. (Teacher’s note: NOTICE THE INCREASED FONT SIZE. WHAT MESSAGE DO YOU THINK THE TEACHER IS TRYING TO SEND TO YOU? PERHAPS THIS IS AN IMPORTANT PARAGRAPH. NOT TO BE RUDE, BUT I’M JUST SAYING...) Many critics vilify modern economists for assuming only selfish motives, for caring only about costs and benefits, and for ignoring man’s more noble side. The economist is, they declare, a moral dwarf. The attack may apply to some—but not to Adam Smith. Not just aware of sympathy and sentiment, he devoted the entire book to these emotions. Furthermore, A Theory of Moral Sentiments pointed to many concepts developed by [Sigmund] Freud more than a century later. Freud’s concept of the “super-ego” the conscience that restrains humans from certain acts and makes them feel guilty when they do not listen, is not too far removed from the adviser that Smith describes. The Wealth of Nations Finally in 1776 [after ten years of writing and refining his ideas] The Wealth of Nations was published. [David] Hume praised it loudly, but warned that popularity would come only slowly. For the first time Smith glorified in a Humean mistake. An instant success, the first edition sold out in six months. But is it a great book? Not only is it a good book, it is a great book. With the hubris that goaded the gods into striking down Greek tragic heroes, Smith stared confidently at the world and delivered nine hundred pages of analysis, prophecy, fact, and fable—most of it clear, charming and aimed at helping the reader to understand. The Wealth of Nations introduces readers to the world of philosophy, politics, and business. with the sharp, skeptical, yet ultimately optimistic Smith as a guide. Just when the Industrial Revolution explodes, Smith confidently points to every player, from farmer to friar to merchant. Furthermore, Smith approaches economic policy without a biased brief for a particular party or class. No one could accuse him of sycophancy or insincerity. Though he finally endorses the rise of the bourgeois, he warns society not to naively succumb to bourgeois blandishments. The Wealth of Nations brought forth a declaration of independence to economists. The full title reveals the key to Smith’ masterpiece: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Notice that Smith focuses on a particular goal: to uncover causal laws that explain how to achieve wealth. The title alone places him in the Enlightenment tradition. The text confirms the suspicion by explaining the laws that guide “economic actors” and then drawing the implications of these behavioral laws for society. “Economic actors” may sound somewhat technical, but Smith simply means people, for everyone is at some point in the day an economic actor. And just as there could be no Hamlet without the Prince, Smith could construct no economics without understanding people. In this he follows the lead of Machiavelli and Hobbes, each of whom saw men as they were, not as they should be. Hobbes spoke of life as “but a motion of limb...For what is the heart but a spring and the nerves so many strings; and the joints but so many wheels giving motion to the whole body...?” (original emphasis). Man is scrutable and peccable. The important natural drives or “propensities” Smith discovers in human nature form the basis of his analysis and the foundation of classical economics. All humans want to live better than they do. Smith finds a “desire of bettering our condition, a desire which, though generally calm and dispassionate, comes with us from the womb, and never leaves us till we go to the grave.” Between the womb and the grave “there is scarce perhaps a single instant in which any man is so perfectly and completely satisfied with his situation, as to be without any wish or alteration or improvement of any kind.” Second, Smith points to “ a certain propensity in human nature...to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another...it is common to all men.” To increase the wealth of nations, Smith argues that society should exploit these natural drives. Government should not repress self-interested people, for self-interest is a rich natural resource. People would be fools and nations would be impoverished if they depended on charity and altruism. Smith states that man almost constantly needs help from others, but it is hoping in vain “to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can show them that it is for their own advantage. In the most cited passage in the history of economic thought, Smith proclaims: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from the regard to their own interests.” (Teacher’s Alert: Did you notice the large font? Hello...? Please nod if you read this advisory) Even those who enjoy slaughtering cattle, brewing beer, or baking cakes, would not do it all day if they were not compensated. Smith never suggests that they are motivated only by self-interest; he simply states that self-interest motivates more powerfully and consistently than kindness, altruism or martyrdom. Put succinctly: Society cannot rest its future on the noblest motives, but must use the strongest motives in the best way. But if everyone charges ahead in his own direction, why does society not resemble anarchy, something like a complex highway intersection with broken traffic lights. Shouldn’t we hear a frightening crash when self-interests clash? If roads cannot be safe without a traffic planning authority designating who shall move, can a community survive without a central planning authority to decide who produces and what is produced? Yes. Not only will it survive, but the community will thrive more than any community with central planning. More surprising, it will surpass both in output and social harmony any economic system based on altruism. Smith had studied astronomy and embraced the idea of a natural harmony in the planets, even if each planet moved in its own orbit. People, he thought, could move in different paths yet harmonize and help each other—but not intentionally. In his classic statement, Smith announces that if all seek to promote their self-interest, the whole society prospers. “He...neither intends to promote the publick interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it...he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” (Emphasis mine) That “invisible hand” becomes the transparent symbol of Smith’s economics.” Yet Smith did not rest his argument on any apparition. The invisible hand merely symbolizes the true orchestrator of social harmony, the free market. Friedrich A. Hayek, one the [20th century’s] most vigorous proponents of the free market, has said that if the market system had not arisen naturally, it would have been proclaimed the greatest invention in human history. For market competition leads a self-interested person to wake up in the morning, look outside at the earth and produce from its raw materials, not what he wants, but what others want. Not in the quantities he prefers, but in the quantities his neighbors prefer. Not at the price he dreams of charging, but at a price reflecting how much his neighbors value what he has done. The Free Market at Work Let us start with our self-interested neighbor John as an example. In contrast to Adam Smith, John wakes up in his own bed rather than the town square. (Teacher’s aside: Smith was a very eccentric man in his personal life. One of the most famous stories concerning Smith is one in which Smith purportedly woke up one night in the middle of a road fifteen miles away from his bedroom and had no recollection how he got there.) While reading the newspaper, John admires the lovely wood sculpture of a vulture that hangs above his dining room table, as if ready to swoop down on table scraps. John really enjoyed carving the vulture. An idea strikes him: Why not sculpt more vultures and sell them? After all, the specially treated wood imported from Tasmania would only cost $50 per vulture, and he can sculpt one per week. He decides to sell the vultures for $200 each, since big profits could make him rich and bring him the things he dreams of, like, big cars and riotous vacations in Acapulco. Most important, though, he loves sculpting. He begins working and rents a shop, inviting neighbors and local art critics to a gala opening. They laugh. He cries. They think the vulture sculptures are hideous. He cries louder. No one buys. Finally his mother offers $49 for one. He gives in—and goes out of business. The invisible hand gives a “thumbs up” approval. Why? Instead of producing something his neighbors wanted, John produced what he wanted. Instead of charging a price they were willing to pay, John charged an exorbitant amount. But in John’s case, no one would pay him as much as it actually cost him to produce the vultures. Didn’t John have to charge more than his costs? No. The answer is not to charge more, but not to produce at all! Why should the invisible hand approve of John going out of business? To make the sculptures, John used up scarce resources. The earth only gives us so much to work with. If John used the valuable Tasmanian wood, no one else could. The invisible hand forces people to give up if they do not produce something more valuable than what they started with. John took $50 worth of wood, carved it up, and gave the vultures worth less. Societies cannot afford to squander resources by subtracting from their values. People who take wood and produce Stradivarius violins or crutches for the disabled increase the value of those resources and enrich society. They deserve applause from the invisible hand. John deserved a punch. Back to the drawing board for John. He pours a cup of tea, curses the vulture above his dining room table, and slams his fist down. Tea jumps out of the cup onto the table. Now he curses himself for spilling tea onto the table he made just a month ago. Inspiration strikes again. Why not, he asks, build tables and sell them? A bit wiser now, he finds a lumber mill that supply wood to him at a cost of about $100 per table. Carving, planing, and fitting will take about two weeks per table. His time, he figures, is worth $200 per week, based on his previous job as a carpenter. Taking into account tools, rent, and other incidentals, he calculates the total cost per table at roughly $575. John window-shops for similar dining room tables and discovers he could sell the tables for $585. Not only will he be able to pay himself $200 per week, but he will also earn a profit. The invisible hand finally gives John a thumbs up. He’s taken scarce resources and brought forth something more valuable than he started with –not according to his own tastes, but according to society’s. So far we have seen the invisible hand encourage and discourage production. But Adam Smith also shows us how the market regulates prices. Remember that Smith’s characters are self-interested. Why does John not raise his table prices above $585 to increase profits? He cannot. If John boosts his prices, profits will plunge, because people will simply bypass his shop and buy from competitors who charge less. Of course, all the furniture-makers could get together and agree to raise prices. But even if they were able to agree, other self-interested people would see the high profits in the furniture business and open shops. Prices and profits signal to entrepreneurs what to produce and what prices to charge. High prices and high profits sound alarms in the ears of entrepreneurs, screaming at them to start producing a certain good. Low profits or losses grab the businessman by the shirt collar and shake him mercilessly until he stops producing. Prices and profits are not simply abstractions, though. What does it really mean if profits are high? It means that people need or want a product. If consumers decide they like compact disc players more than record players, demand will rise for discs, and producers will be able to charge more. But record player manufacturers will respond to the signals by producing fewer record players and more disc players; workers will be shifted from one factory to another; and the price will return to normal. Over the past decade prices for personal computers have dropped, not only because costs have dropped, but also because so many high-technology manufacturers have entered the competition for profits. In the long run no industry should earn more than a normal profit. The free market automatically induces self-interested Johns to satisfy strangers. No central planner need call, no taskmaster need coerce. Division of Labor Adam Smith delivered on his promise to show how the invisible hand regulates output, price, and output. But the cheery Scotsman also promised to teach us what increases the wealth of nations...Happily he wins again with a neat three word answer: division of labor. Smith argued his case logically and empirically. The empirics come to life as he describes a pin factory, again in one of the most famous passages in economic thought. Mark Twain said that classics are books everyone owns, but no one ever bothers to read. Even more sadly, classics often become rather boring clichés, and we can miss the force and drama they had when they originally appeared. Imagine the initial power of the power of the following passage, for it appeared before factories were common and when groups of only three or four people produced most of the world’s goods: A workman not educated to...the trade of the pinmaker...could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. But in the way which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire, another staights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands...I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where...each person...[averaged] four thousand eight hundred pins a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them make twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day. Just by specializing and dividing the tasks, one day’s output can explode by 400,000 percent! How can Smith possibly explain this? Are we about to be introduced to the invisible foot or another impartial ghost who actually works for us while we sleep? To be fair to Smith, he never promised a 400,000 percent leap in every situation. But he did proclaim three ways in which division of labor lifts output: 1. Each worker develops more skill and dexterity in their particular task. 2. Workers waste less time changing from one task to another. 3. Specialized workers will more likely invent machinery to help with the particular task they focus on daily. Notice that while Smith begins by praising division of labor for its heightened productivity, he ends up crediting division of labor fro technological advancement. To spark efficiency, jobs should be divided by task...But [Smith] warned that division of labor leads to a divergence in wage rates for different tasks. Smith’s complex hypothesis for wage rates preclude a neat and concise discussion. But he did give economic theorists cogent grounds for explaining why one group gets paid more than another. 1. A job may entail disagreeable conditions, and thus few accept employment unless wages compensate them...A window washer at the top of the Empire State Building receives more than a [worker] who washes a Formica lunch counter. 2. Some jobs may require special training. (For example: engineers.) 3. An irregular or insecure job may pay more. Construction workers receive more per hour than other similarly trained laborers, because weather conditions prevent them from working as many hours. 4. When high degrees of trust are required, wages rise. Because lay persons cannot assess the value of a diamond, many people feel more comfortable buying from a pricey but trustworthy store like Tiffany’s than from a discounter. 5. When the probability of success is low, the payoff for success will be high. Lawyers in civil suits often accept cases on contingency; that is, they get paid only if they win which often means they get paid at a higher rate than other court personnel such as bailiffs and stenographers. Smith did not believe that all economic actors displayed perfect rationality. He suspected that people in risky professions overestimate their chances of success and, therefore, end up with lower incomes than they expect. (As an example, think about miners in a gold rush.) Division of Labor Among Towns and Countries Smith never promised that division of labor alone brings wealth to a nation...Free trade among manufacturers, suppliers, towns, and cities is also necessary. What good are 10,000 pins if they cannot be trade because of restrictions or high transportation costs. The manufacturer might as well make 20 or perhaps none. Furthermore, division of labor can take place among towns, not just among workers in a factory. Particular towns can specialize, just as particular individuals can. Boise may produce wheat, while Boston produces computers. The point, the wealth of a nation grows if markets expand; that is, if more and more areas are hooked up to trade routes.