ENFOQUE DEL PACIENTE ICTERICO

advertisement

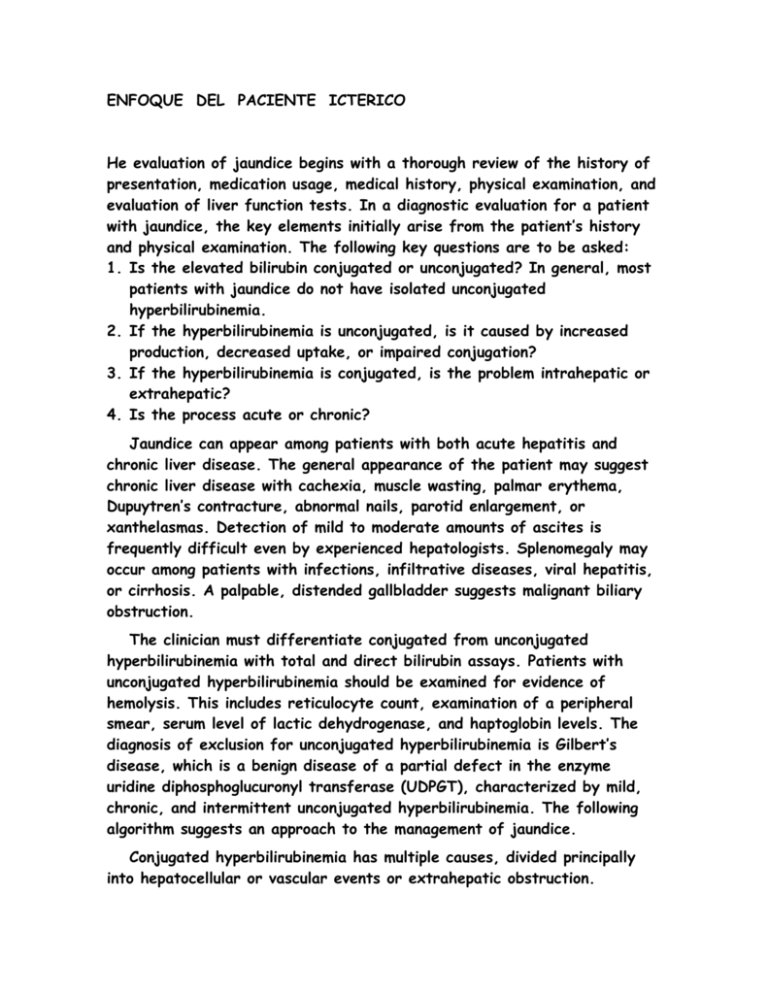

ENFOQUE DEL PACIENTE ICTERICO He evaluation of jaundice begins with a thorough review of the history of presentation, medication usage, medical history, physical examination, and evaluation of liver function tests. In a diagnostic evaluation for a patient with jaundice, the key elements initially arise from the patient’s history and physical examination. The following key questions are to be asked: 1. Is the elevated bilirubin conjugated or unconjugated? In general, most patients with jaundice do not have isolated unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. 2. If the hyperbilirubinemia is unconjugated, is it caused by increased production, decreased uptake, or impaired conjugation? 3. If the hyperbilirubinemia is conjugated, is the problem intrahepatic or extrahepatic? 4. Is the process acute or chronic? Jaundice can appear among patients with both acute hepatitis and chronic liver disease. The general appearance of the patient may suggest chronic liver disease with cachexia, muscle wasting, palmar erythema, Dupuytren’s contracture, abnormal nails, parotid enlargement, or xanthelasmas. Detection of mild to moderate amounts of ascites is frequently difficult even by experienced hepatologists. Splenomegaly may occur among patients with infections, infiltrative diseases, viral hepatitis, or cirrhosis. A palpable, distended gallbladder suggests malignant biliary obstruction. The clinician must differentiate conjugated from unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia with total and direct bilirubin assays. Patients with unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia should be examined for evidence of hemolysis. This includes reticulocyte count, examination of a peripheral smear, serum level of lactic dehydrogenase, and haptoglobin levels. The diagnosis of exclusion for unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is Gilbert’s disease, which is a benign disease of a partial defect in the enzyme uridine diphosphoglucuronyl transferase (UDPGT), characterized by mild, chronic, and intermittent unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. The following algorithm suggests an approach to the management of jaundice. Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia has multiple causes, divided principally into hepatocellular or vascular events or extrahepatic obstruction. Hepatocellular causes of a conjugated bilirubinemia include infectious hepatitis, medication-related hepatitis or cholestasis, autoimmune liver disease, alcohol injury, total parenteral nutrition, among many other causes. Further evaluation of these causes should include hepatitis viral serologic testing and autoimmune markers such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA) or antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA). Infectious causes of hyperbilirubinemia are listed in Table 7-1 TABLE 7-1. Infectious Causes Of Hyperbilirubinemia Bacterial cholangitis Candida infection Hepatitis virus A, B, or C infection Bacteroides infection Cytomegalovirus infection Syphilis Epstein-Barr virus infection Toxoplasmosis Liver abscess Brucellosis Sepsis syndrome Q fever Toxic shock Rickettsia Escherichia coli infection Leptospirosis Klebsiella infection Malaria Pseudomonas infection Yellow fever Shigella infection Legionella infection . They range from bacterial and viral to fungal organisms and involve the liver either directly with an abscess or indirectly through circulating cytokines or toxins. Medication-related sources of hyperbilirubinemia, shown in Table 7-2, are divided into hepatocellular, cholestatic, and mixed causes. TABLE 7-2. Common Drugs Associated With Hyperbilirubinemia Hepatocellular causes Cholestatic causes Mixed causes Acetaminophen Amitriptyline Acetohexamide Alcohol Androgenic steroids (B) Allopurinol Amiodarone Atenolol Ampicillin Azulfidine Augmentin Augmentin Carbenicillin Azathioprine Cimetidine Clindamycin Bactrim (D) Dapsone Colchicine Benzodiazepines Disulfiram Cyclophosphamide Captopril Gold Diltiazem Carbamazole Hydralazine Ketoconazole Chlordiazepoxide (D) Lovostatin Methyldopa Clofibrate Nitrofurantoin Nifedipine Cyclosporin Phenytoin Propylthiouracil Dapsone Sulfonamides Pyridium Disopyramide Tetracycline Pyrazinamide Erythromycin Quinidine Estrogens (B) Rifampin Ethambutol Salicylates Floxuridine Verapamil 5-Flucytosine Fluoroquinolones Griseofulvin Haloperidol (D) Labetolol Nicotinic acid Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs Penicillins Phenothiazines (D) Phenytoin Tamoxifen Tegretol Thiabendazole (D) Thiazides Thiouracil Tolbutamide (D) Tricyclics (D) Verapamil Zidovudine (B), Bland or noninflammatory cholestasis; (D), ductopenic cholestasis or vanishing bile duct syndrome. Liver function tests other than specific viral or autoimmune markers can be helpful in the determination of causes or outcomes of liver disease. Aminotransferases are representative of the parenchymal hepatic injury that occurs with viral, autoimmune, and ischemic hepatitis, with values typically in the several hundred range. Aminotransferase values of 1000 U/L or more can represent severe acute viral hepatitis, fulminant hepatic failure, or liver disease induced by drugs such as acetaminophen or toxins from ischemic necrosis. Hyperbilirubinemia can arise from both parenchymal hepatic injury or obstructive disease. The level of alkaline phosphatase may be disproportionately elevated in patients with partial obstruction, multiple intrahepatic lesions, granulomatous disease, or primary biliary cirrhosis. If the alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels are markedly elevated, the presence of a common bile duct stone should be excluded. An elevation alkaline phosphatase level with a normal bilirubin level may occur in the presence of partial extra- or intrahepatic obstruction. Therefore, alkaline phosphatase level is a more sensitive test for biliary obstruction than is bilirubin level. If tumors of the liver are suspected on the basis of a history of extrahepatic primary tumor or the sudden decompensation of cirrhosis, additional testing by means of serum -fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), or CA19-9 levels or computed tomographic (CT) scanning of the liver is necessary. Ultimately, the diagnosis of liver tumor, whether primary or metastatic, derives from adequate radiographic imaging or histologic examination. In the algorithm for such an evaluation, metastatic disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, adenoma, and hemangioma all can be suggested with the appropriate radiographic test. Ultrasonography of the liver can be a helpful starting point if an abnormal AFP level suggests a tumor, but CT scanning with dual-phase contrast or magnetic resonance imaging is most helpful in the diagnosis. Vascular events in the liver (see algorithm) can result from hepatic ischemia either from ischemic hepatitis in acute hypotensive shock or left ventricular dysfunction. Passive congestion to the liver can arise from right ventricular dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, or tricuspid regurgitation. Hepatic outflow obstruction, traditionally known as BuddChiari syndrome, usually involves hepatic venous obstruction or a vena caval web. However, functional Budd-Chiari syndrome can derive from the sources of passive congestion to the liver just mentioned. The diagnosis of Budd-Chiari sydrome is heightened by a history of thrombotic disorders and polycythemia vera and suggested by findings at Doppler ultrasonography of the hepatic vein. The hepatic vein, however, can be the Achilles’ heel of the liver vasculature at Doppler ultrasonography, because this vein can have thrombosis missed or overdiagnosed because of its small size, because the liver is firm and cirrhotic, or because of the passive flow of severe tricuspid regurgitation. Use of diuretics, surgical shunting, and liver transplantation are treatments for the symptoms and complications of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ultrasonography is the first study used to detect biliary obstruction. Despite some caveats about missing intraductal stones without biliary dilation and the fact that ultrasonography is operator dependent, there are few false-positive test results, and ultrasonography remains the initial screening test for the evaluation of biliary obstruction in most instances. CT scanning has a sensitivity similar to that of ultrasonography, but the results rely less on operator proficiency. In 60% to 90% of instances, obstructions are found where they are indicated to be on the CT scan, and CT scanning is not impeded by fat, as is ultrasonography. However, CT scanning is more expensive than ultrasonography, requires intravenous administration of contrast medium in many instances, and is not more sensitive. Invasive tests include endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), and liver biopsy. ERCP is 90% successful regardless of the presence or absence of ductal dilation and can help localize the site of obstruction in more than 90% of patients. It is particularly helpful in diagnosing common duct stones. Because it has therapeutic capabilities, ERCP allows some patients to avoid surgical treatment. ERCP is helpful if a stricture due to chronic pancreatitis is suspected. The main reasons for lack of visualization of the biliary tree during ERCP are prior operations (e.g., Roux-en-Y anastomosis) and an inability to cannulate the sphincter of Oddi. The morbidity rate is 2% to 3%, somewhat less than with PTC. The most common complications are pancreatitis and cholangitis. The rate of sepsis is less than 1% if prophylactic antibiotics are given when obstruction is suspected. The decision to pursue ERCP or PTC depends on the presumed site of obstruction, the presence of coagulopathy or ascites, and the expertise of the radiologists and gastroenterologists. PTC and ERCP are sometimes used together, especially if ultrasound examination reveals ductal dilation, and a cytologic specimen is needed for determining the presence of malignant growth. Strictures should be differentiated from cholangiocarcinoma. This often necessitates cytologic analysis or biopsy of the lesion. If one of the invasive tests is unsuccessful, the complementary test can be attempted. PTC depicts the biliary tree in 90% to 100% of patients with dilated ducts. PTC is the preferred modality when in the setting of proximal biliary or intrahepatic ductal dilation the area of stenosis within the bile duct cannot be adequately accessed by means of ERCP. Common bile duct dilation is represented in Fig. 7-1 with ERCP demonstration of two obstructive stones. Therapeutic removal of obstructive stones can be accomplished with basket retrieval (Fig. 7-2). The diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is shown in Fig. 7-3 with cutoff of the pancreatic duct and incomplete filling or drainage. Enlargement of the head of the pancreas by a mass can result in obstruction of the biliary and the pancreatic duct (Fig. 7-4), the so-called double-duct sign. Intrahepatic ductal dilation can exist in multiple conditions, such as distal bile duct obstruction or both intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary disease, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis. The intrahepatic duct dilation of primary sclerosing cholangitis is shown in Fig. 7-5, which has scattered areas of narrowing or beading. ERCP can also be useful in demonstrating bile leakage or fistula, as in this image (Fig. 7-6) of a patient with fistula formation and complete common bile duct transection after cholecystectomy. The diagnosis and management of pancreatic or bile duct cancer involves the pivotal role of ERCP. Pancreatic cancer with biliary obstruction can lead to common bile duct and intrahepatic duct dilation (Fig. 7-7). Proximal hepatic duct dilation in the same patient with pancreatic cancer as in Fig. 7-7 is shown in Fig. 7-8 after balloon dilation. The therapeutic role of ERCP in alleviating obstruction caused by pancreatic cancer in this patient is demonstrated in Fig. 7-9. Use of a Wallstent prosthesis through the strictured site decreased the biliary dilation. Biliary dilation from an obstructive lesion of ampullary carcinoma is shown in Fig. 7-10. Recurrent cholangiocarcinoma after liver transplantation can be demonstrated by means of ERCP (Fig. 7-11). The therapeutic role of ERCP in common bile duct stricture is shown in Fig. 712 in the case of a patient with a biliary stricture after liver transplantation. An endoscopic view of a stent placed to manage obstructive ampullary adenocarcinoma is shown in Fig. 7-13. A Wallstent prosthesis traversing the ampulla for bile duct carcinoma is shown in Fig. 7-14. The histologic features of cholestasis are defined as either intrahepatic cholestasis marked by bile duct pigment within hepatocytes or extrahepatic cholestasis with bile duct pigment within the bile ducts. The presence at liver biopsy of bile duct plugs or bile duct proliferation with or without dilation is further supportive of extrahepatic obstruction. Figure 7-15 is a representative liver biopsy specimen at low power from a patient with extrahepatic obstruction. Figure 7-16 shows a specimen from a patient with intrahepatic cholestasis. The role of liver biopsy in the treatment of a patient with jaundice is most important in identifying the cause of cholestasis but not merely to confirm its presence. The performance of a liver biopsy is essential in the diagnosis of hepatocellular diseases such as autoimmunity, worsening abnormal liver function tests of unclear causation, some types of viral hepatitis, cholestatic diseases of primary biliary cirrhosis, Wilson disease, or the establishment of occult cirrhosis. Complications after liver biopsy occur with an incidence ranging from 0.1% to 3.0%. Overall, liver biopsy is a safe procedure, as is ERCP. However, liver biopsy is invasive, and careful consideration is needed in the care of a person at risk for complications. Patients with coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, or ascites may need blood products or an alternative route of biopsy, such as a transjugular approach. Transjugular liver biopsy is a well-established alternative for obtaining liver tissue. For patients with renal insufficiency or taking warfarin, however, ultrasound-guided liver biopsy can be performed with desmopressin (DDAVP) or a gelatin foam plug.