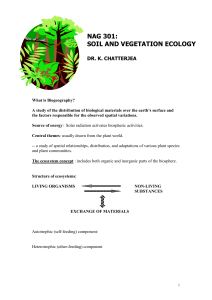

Values In The Biosphere Reserve

advertisement