The-American-Revolution,-1775-1783

advertisement

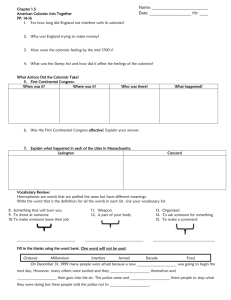

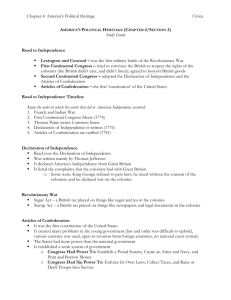

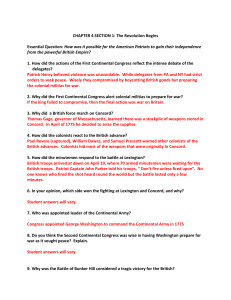

12. The American Revolution, 1775-1783 Declaration of Independence - The Continental Congress In response to the Patriot’s defiant outburst and the destruction of British goods during the Boston Tea Party, Parliament enacted several laws to tighten its control over the colonies. The Coercive Acts, called the Intolerable Acts by Americans, punished primarily Bostonians but affected people in all thirteen colonies. The legislation increased Americans’ resentment toward Britain and galvanized the Patriot resistance. In September 1774, delegates from twelve colonies—the governor of Georgia refused to send a representative—met at Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia to fashion a common response to the Intolerable Acts. John Adams, George Washington, Samuel Adams, and Patrick Henry were among the fifty-five members of the First Continental Congress who discussed various ideas and drafted resolutions to address colonial grievances. One proposal, the Plan of Union, presented by Pennsylvanian Joseph Galloway, called for an American government consisting of a president appointed by the king and a council selected by the colonies. The American officials would regulate internal colonial affairs and possess the power to veto parliamentary acts affecting the colonies, but remain subordinate to Parliament and the Crown. Galloway’s moderate proposal was defeated by a vote of six colonies to five. Paul Revere then submitted the Suffolk County Resolves that rejected the Intolerable Acts and called upon Americans to prepare for a British attack. After endorsing the resolutions, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Rights and Resolves, drafted by John Adams. Drawing upon the “immutable laws of nature” and rights of Englishmen, the declaration argued that Americans were entitled to legislate for themselves “in all cases of taxation and internal polity,” conceding to Parliament only the power to regulate “our external commerce.” During the course of nearly two months, the First Continental Congress endorsed many documents and open letters to the people of Great Britain and Canada explaining their actions. In an appeal to the king, edited by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, the delegates blamed the crisis on Parliament and Lord North’s administration. Americans were not yet demanding independence, but sought the right to participate in a free government that protected their liberties within the British Empire. Before adjourning, the delegates organized the Continental Association that called for a complete boycott of British goods. The delegates agreed to meet again in May 1775 to discuss Britain’s response to their decisions. Tension between the colonies and Great Britain escalated following Parliamentary elections that gave Lord North’s government a majority for the next seven years. King George declared the New England colonies to be in a state of rebellion, and Parliament supported his decision to coerce the colonies. Resistance was also stiffening in America. Colonists increased their efforts to enforce the British boycott by appointing association committees to monitor compliance and expose all violators. People caught breaching the boycott were often tarred and feathered. The failed attempts to negotiate a resolution with Britain prompted many colonists to secure weapons and conduct military drills to prepare for the possibility of war. In January 1775, orders went out from London to prohibit the meeting of the Second Continental Congress. The following month, Parliament declared that Massachusetts was in a state of rebellion and military reinforcements were dispatched to America under the command of three senior generals—William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne. On the night of April 18, General Thomas Gage sent British troops marching from Boston toward Concord. The soldiers were ordered to seize colonial weapons and gunpowder and arrest John Hancock and Samuel Adams, whom the British considered to be the leaders of the Patriots. As the redcoats entered Lexington, they encountered a band of colonial militia called "Minute Men" who were trained to fight on a minute's notice. The two groups exchanged heated words and, as the Americans slowly dispersed, a shot was fired. The British continued their march after a brief skirmish, leaving behind eight dead Americans. At the North Bridge in Concord, the redcoats met a sharper fight, and casualties were sustained by both sides. American essayist and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson later immortalized the event as “the shot heard round the world.” The Revolutionary War had begun. On May 10, 1775, representatives from all thirteen colonies met at the State House in Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress. Joining many members from the First Congress were Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, and Thomas Jefferson, a young Virginia planter who had recently written essays criticizing the British monarchy and supporting the rights and liberties of Americans. Also representing Virginia was George Washington, a veteran of the French and Indian War, who attended sessions dressed in his colonel's uniform. Many cautious representatives from the middle colonies feared that radical New England delegates were pushing the colonists into open rebellion. After much debate, the fighting in Massachusetts finally convinced a majority of the delegations that a military defense plan was necessary. Washington’s experience in battle and his willingness to defend America influenced congressional members to appoint him commander-in-chief of the newly formed Continental Army. The selection of Washington to lead the army appeased many conservatives who distrusted the boisterous Bostonians. Washington’s wealth, and his refusal to accept pay for his position, quashed suspicions that he was a fortune seeker. While the battles at Lexington and Concord pressed many colonists into joining the military forces gathering near Boston, members of the Second Continental Congress believed they could still persuade the king and Parliament to resolve the colonists' grievances without more bloodshed. In June 1775, Congress approved John Dickinson’s "Olive Branch Petition," which was aptly named because of its suppliant tone. It professed American loyalty to the king and begged him to intercede for the Patriots against his controlling Parliament and ministers. The following day, the delegates endorsed the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, written by Dickinson and Jefferson. It proclaimed: “Our cause is just. Our union is perfect.” American Patriots were prepared to fight to preserve their liberties as British citizens. In November, however, word arrived that King George III refused to receive the Olive Branch Petition and officially proclaimed the colonies to be in “open and avowed rebellion.” As the fighting between the Patriots and the redcoats intensified, the Second Continental Congress assumed the functions of a national government. It appointed commissioners to negotiate with Indian tribes and foreign governments in an effort to form military and diplomatic alliances. It also authorized the creation of a navy and several battalions of marines, and organized a postal system headed by Benjamin Franklin. 13. The Revolutionary War - Major Battles In 1774, as a response to the Boston Tea Party, the British Parliament passed a series of acts, called the Coercive Acts. These acts crushed many of the chartered rights of colonial Massachusetts and infringed on the rights of the other colonies. Americans reacted with trade boycotts, and they also began to slowly unite and take political power into their own hands. Americans were not yet calling for independence, but formation of the First Continental Congress, combined with the colonists’ reactions to the Coercive Acts, led King George III to believe the colonies were in a state of rebellion. In April 1775 on orders from the Crown, British soldiers, or redcoats as Americans referred to them, marched west from their station in Boston to Lexington and Concord. They were to confiscate colonial weapons and gunpowder and capture John Hancock and Sam Adams, the leaders of the “rebel militia.” When local Patriots heard the purpose of the British troops, they sent Paul Revere and William Dawes on their famous rides to alert the countryside and warn Hancock and Adams that the British were coming. The Massachusetts Patriots, as they were calling themselves, had been accumulating arms and training “Minute Men,” so named because they were said to be ready to fight in a minute. When the redcoats arrived at Lexington, about 70 Minute Men refused the British solders’ orders to disperse, and a shot was fired. No one knows which side fired the shot, but it was, in the often quoted phrase of Ralph Waldo Emerson, "the shot heard 'round the world." A flurry of gunfire ensued, leaving several Minute Men dead and wounded. The British troops pushed on to Concord, destroyed whatever supplies the Patriots had not removed, and were forced to retreat by a growing number of American militiamen. At the end of what many consider the first day of the Revolutionary War, the British troops had suffered over 250 casualties, while the Americans had fewer than 100 casualties. A British General reported to London that the rebels had earned their respect. The Second Continental Congress met the next month, on May 10, 1775, in Philadelphia, with representatives from all 13 colonies in attendance. Congress first dealt with the disorganized military. The assembly organized the troops who had gathered around Boston into the Continental Army, appointing George Washington Commander-in-Chief. Although Washington had never commanded more than twelve hundred men, his participation in the French and Indian War made him one of the most experienced officers in America. The choice of Washington as Commander-in-Chief was also a shrewd political compromise. Many representatives were wary of the rebellious spirit coming from the northeastern colonies. Washington had great leadership skills, was wealthy, aristocratic, and from Virginia, which appeased everyone. Once the Continental Congress dealt with the military crisis, the delegates drafted an appeal to King George and Parliament hoping to reach a compromise settlement. In July 1775, the Continental Congress issued two major documents. The first was the “Olive Branch Petition” professing American loyalty and advancing one last plea to the King to prevent further hostilities. The second, the “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms,” traced the history of the controversy, condemned the British for everything they had done since 1763, and rejected independence but affirmed the colonists’ purpose to fight for their rights. King George III refused to even look at the Olive Branch Petition, and in August 1775 declared the colonies to be in open rebellion. The King ended all hopes of reconciliation when he hired thousands of German troops, called Hessians, to help defeat the rebellious Americans. The colonists felt the king was going “outside the family” by hiring Hessians mercenaries, which only increased the hostilities and pushed them further from British rule. Meanwhile, both British and colonial forces around Boston had been building. The Patriots seized Breed’s Hill on the high ground of Charlestown peninsula, overlooking Boston. Breed’s Hill has erroneously been called Bunker Hill and was actually closer to Boston than Bunker Hill—the source of the battle’s name. British General Thomas Gage launched a frontal attack on June 17, 1775, with over 2,000 soldiers. Twice the redcoats marched up Breed’s Hill toward the strongly entrenched, sharp shooting Americans, only to be driven back after suffering heavy losses. On the redcoats’ third attempt, the colonists ran out of gunpowder and were forced to abandon the hill. More than 1,000 redcoats had fallen, with colonial losses around 400, making it a morale-boosting experience for the newly formed Continental Army. The Battle of Bunker Hill greatly affected both the British and American forces. After the excessive losses the British suffered, they entered subsequent battles with greater caution. On the other hand, the American Congress realized that they needed more support and encouraged all able-bodied men to enlist in the militia. Tensions between the Loyalists and Patriots continued to build. In the fall of 1775, the rebels planned an attack on British troops in Quebec, thinking a successful assault would add a fourteenth colony to their cause. This was in direct conflict with the idea that they were fighting a defensive war, which is what most Americans felt to this point. Troops under command of Richard Montgomery advanced by way of the St. Lawrence River to Lake Champlain, while troops under Benedict Arnold struggled northward through the Maine woods. Their attack was unsuccessful, Montgomery was killed, and Arnold was wounded and retreated with the remainder of his army down the St. Lawrence River. Fighting persisted throughout the thirteen colonies. Virginia’s governor raised British Loyalist forces who set fire to the town of Norfolk in January 1776. In March, the British were finally forced to evacuate Boston and move their base of operation to New York as they felt they needed to be more centrally located in the colonies for a sustained war effort. In the south, redcoats attacked Charleston harbor, but the Patriot militia built a fort to protect them from British fire. They inflicted over 200 redcoat casualties and forced the British fleet to retire. While these small battles continued throughout the colonies, Americans drew closer to declaring their independence. In 1776, Thomas Paine published his pamphlet Common Sense, in which he discussed the wavering American loyalty to the crown as contrary to “common sense.” One key idea in Paine’s pamphlet was that an island should not rule a continent. Paine’s pamphlet, coupled with the desire of more and more colonists to make a clean break from England, led to the creation of the Declaration of Independence, which was formally approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. Meanwhile, British soldiers led by General William Howe landed on the undefended Staten Island. By mid-August 1776, over 30,000 men had gathered there—the largest single force assembled by the British in the eighteenth century. In response, General Washington led his forces out of Boston south toward New York, but still could only gather about 18,000 Continentals and militiamen. General Howe crossed from Staten Island to Brooklyn, and in the Battle of Long Island he inflicted heavy losses and forced Washington to evacuate. At that point, General Howe could have crushed the American forces, but he did not move quickly enough. A timely rainstorm enabled Washington’s troops to escape Manhattan Island northward across the Hudson River and they then marched south through New Jersey to the Delaware River. General Howe established outposts at Trenton, Princeton and other strategic points and settled in at New York to wait out the winter. Washington seized the initiative, and on Christmas night 1776, he crossed the ice-clogged Delaware River and surprised and captured nearly 1,000 Hessian soldiers at the British Trenton garrison who were sleeping off the effects of too much Christmas rum. A few days later, Washington defeated a smaller British detachment led by General Cornwallis at Princeton. The campaigns of 1776 left the British with a central stronghold at New York. The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, however, revealed Washington at his military best. This boosted American morale and convinced many men whose enlistments were up at the end of the year to continue fighting with the Continental Army. In the spring of 1777, the British devised an intricate scheme for capturing the Hudson River Valley and cutting off New England from the rest of the colonies, crushing the rebellion. General Burgoyne was to lead his army from Canada down Lake Champlain toward Albany. General Howe’s troops in New York were to advance up the Hudson River to meet Burgoyne near Albany. A third force was to come in from the west by way of Lake Ontario down the Mohawk River Valley and meet up with Howe and Burgoyne. General Burgoyne began his invasion with over 7,000 troops. Accompanied by a huge baggage train full of his personal belongings and the wives and children of many of his men, his troops quickly became bogged down in the dense woods north of Saratoga. Meanwhile, General Howe disregarded the plan for capturing the Hudson River Valley and instead took the bulk of his army south to attack Philadelphia, the Patriot capital. Washington, sensing Howe’s purpose, took his army from New Jersey to meet the new threat. In September 1777, Howe pushed Washington’s forces back in two battles at Brandywine Creek and Germantown, and proceeded to occupy Philadelphia. General Howe and his troops settled into the comfort of Philadelphia for the winter, thinking that capturing the capital would surely crush the colonial spirit. Benjamin Franklin jested that General Howe had not taken Philadelphia, but Philadelphia took him. Washington’s Continental Army retreated into winter quarters at Valley Forge. In the meantime, disaster was about to befall General Burgoyne who had finally made it just North of Albany. The American militia forces under Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold began to build up around Albany. The militia struck two serious blows against the British, one west of Albany at Oriskany, New York and another east at Bennington, Vermont. American reinforcements continued to gather, and soon militia in every direction pinned down Burgoyne. On October 17, 1777, Burgoyne surrendered to General Gates at Saratoga, and over 5,000 British prisoners were marched off to Virginia. The Patriot triumph at Saratoga changed the course of the war. It revived the faltering colonial cause, and it also convinced France to give the colonists urgently needed foreign aid. 14. Articles of Confederation - Forming a Confederation The thirteen American colonies had finally become "free and independent states," but the task of knitting together a nation still remained. The Revolutionary War had served as the catalyst for the American debate over the form of government that would best serve an independent republic. The colonists posed a range of questions about their new nation’s government. They tried to determine who ‘the people’ were in the Declaration of Independence, and how their definition would affect slaves, women, those without property, and Native Americans, among others. While the war was still being waged, notions of what republicanism meant were being formed on a state by state basis. Many, like Thomas Paine, felt that republicanism was a moral code of behavior, as well as a system of government in which the supreme power of the country is vested in an electorate. Citing England’s history, he believed that when citizens became selfish or corrupt the republic would give way to tyranny. Fewer supported the opposing point of view that the importance of individual self-interest was the basis of a republic's strength. In 1776, the Continental Congress called the colonies to draft new state constitutions. As the states formed their constitutions, colonists considered the balance of power between the state governments and the government at the national level. Using their colonial charters as a basis, the states implemented their own ideas for the role of government in society. All of the new constitutions were built on the foundation of colonial experience combined with English practice and showed the impact of republican ideas. Some state constitutions reflected the approach that the sovereignty of the states would rest on the authority of the people, while others allowed the government to wield more power. This debate helped to frame each of the state constitutions. Connecticut and Rhode Island created their constitutions by simply removing any language that referenced colonial ties. In contrast, most of the other colonies reworked their constitutions in great detail, trying to capture the spirit of republicanism, an ideal that had long been praised by Enlightenment philosophers. The Massachusetts assembly contributed an important procedure to American constitution-making when they called a special convention to draft their constitution. Once the document was created it was then submitted directly to the people at town meetings for ratification, with the provision that two-thirds would have to approve it, which they did. The procedures used by the Massachusetts convention were later imitated during drafting and ratification of the federal Constitution. Massachusetts also had a much stronger executive branch than the other states did. The new state constitutions varied mainly in detail. All of them combined the best of the British government, including its respect for status, fairness, and due process, with unique American inclusions of individualism and control over excess governmental authority. Each constitution began with a bill of rights, which protected people’s civil liberties against all branches of the government. Virginia's bill of rights served as a model for all the others, and included a declaration of principles, such as popular sovereignty, rotation in office, freedom of elections, and a list of fundamental rights such as humane punishment, speedy trial by jury, freedom of the press and of conscience, and the right of the majority to reform or alter the government. Other states added to this list of rights, including guaranteed freedom of speech, of assembly, and of petition. State constitutions frequently included the right to bear arms, to a writ of habeas corpus, and to equal protection under the law. Generally the states incorporated a separation of powers to safeguard against abuses. Many limited the powers of the executive and judicial branches, while increasing the power of the annually elected legislative branch to ensure that much of the authority rested with the people. The state constitutions had some obvious limitations. The constitutions were established to guarantee people their natural rights, but they did not secure equality for everyone. Women were not allowed to participate in politics, many southern colonies excluded slaves from their inalienable rights as human beings, and no state permitted universal male suffrage. The Revolution also left the colonists with the responsibility of creating a new national government. Even before the Peace of Paris, the delegates of the Continental Congress recognized that they were essentially a legislative body exercising governmental powers without any constitutional authority. Plans to frame a permanent government were started as early as July 1776 when a committee headed by John Dickinson prepared to draft a national constitution. Congress debated the “Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union” for more than a year before submitting them to the states for ratification. All of the states were required to approve the Articles before they would go into effect. They were promptly ratified by every state except Maryland who insisted that the seven states who claimed lands west of the Appalachians —New York, Virginia, Massachusetts, Connecticut, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia—should cede them to Congress Maryland cited several reasons for this requirement. The claims in the west were overlapping and vaguely defined. The six states without western lands felt those who did have land holdings would not have retained them if it had not been for the unified efforts of all the states in the Revolution. Colonies claming western lands had an unfair advantage because they could sell the property off to pay war debts, while those colonies without western lands would have to rely heavily on tax receipts to recoup war costs. Maryland finally gave in when New York surrendered its western claims, and Virginia finally relinquished a large region north of the Ohio River in early 1781. Thus, the transfer of public land from the states to the central government helped to solidify the union. Congress promised to use these western lands for the “common benefit” by creating a number of new states. The Articles of Confederation were put into effect in March of 1781, just a few months before the victory at Yorktown. The Articles linked the 13 states together to deal with common problems, but in practice they did little more than provide a legal basis for the limited authority that the Continental Congress was already exercising. The Congress still had no courts, no power to levy taxes, no power to regulate commerce, and no power to enforce its resolutions upon the states or individuals. Each state had a single vote regardless of population. A vote from nine states was required to approve bills dealing with war, treaties, coinage, finances, or the military, while amendments to the Articles themselves required unanimous ratification. In whatever areas Congress held authority, it had no way of enforcing the powers it did have. Despite their weaknesses, the Articles were the most practical form of government for the new nation. The establishment of a more formal and powerful central government would have caused dissention and prolonged debates between the colonies at a time when the focus needed to be on the Revolution that had yet to be won. The Articles also provided a clear stepping-stone to America’s present Constitution by promoting the formation of a union and clearly outlining the powers the central government could exercise. 15. The Confederation Faces Challenges - International Relations During the years following the American Revolution, foreign relations remained contentious. The Revolution freed American trade from the restrictions of British mercantilism. Americans could now trade directly with foreign powers, and a valuable Far Eastern trade developed where none had existed before. The Empress of China sailed from New York to Canton, China, carrying furs, cotton, and the spice ginseng and returning with silk, tea, and other luxury goods of East Asia. Exclusion from the British imperial trade union also resulted in great losses for the Confederation. Immediately after the Revolution, Parliament debated the issue of trade with the former colonies. Some argued that restricting trade with America was wasteful, and that if trade were restricted neither party would benefit. Others, still angry about the Revolution, argued against a commercial treaty with the former colonists. Lord Sheffield, a member of the British Parliament, in his 1783 pamphlet entitled Observations on the Commerce of the American States, argued that Britain could trade with America without signing a treaty and making any concessions. Parliament voted to increase exports to America, while at the same time holding American imports to a minimum. Parliament also refused to repeal Britain’s Navigation Laws, which prohibited American commerce with the British West Indies. The effect was devastating to American trade in wheat, fish, and lumber. West Indian demand for American goods remained strong, so shippers resorted to smuggling products to the islands on a much smaller scale. British merchants began to ship low-priced goods of all kinds to the Confederate States. Americans eagerly purchased British products that they were deprived of during the Revolution. The influx of cheap foreign goods further aggravated the already bleak economic situation for American merchants. Some demanded that the Confederation impose restrictions on Britain’s imports, but the Continental Congress did not have the power to regulate commerce, and the states could not agree on a uniform tariff policy. America and Britain were also involved in a dispute over post-war borders. Britain promised to withdraw all of its troops from America after the Revolution, and they did from the settled portions of the 13 states. In the northern frontier, however, the British refused to surrender several military posts on American soil that ran from the northern end of Lake Champlain down to the tip of the Michigan peninsula. The British justified their position by citing America’s failure to honor the terms of the peace treaty. Specifically, America did not allow British creditors to collect pre-war debt and also did not restore confiscated Loyalist property as promised. The British soldiers remained in their positions to gain the favor of the local Indian tribes and deter America from future attacks on British-held Canada. Although Spain had also recently been at war against Britain, it quickly became clear that they were not an American ally. During the peace negotiations Spain had won back Florida and the Gulf Coast region east of New Orleans. Spain also controlled the mouth of the Mississippi River, which the growing American settlements in Kentucky and Tennessee used to transport their farm products to eastern and European markets. In 1784, Spain closed the river to American commerce. Eventually, the Spanish governor reopened the river but required Americans to pay a tariff to use the passageway. Spain captured Fort Natchez during the war, and although it was far north of Spanish holdings and well into American territory, they refused to relinquish it. Like the British, the Spanish made alliances with local Indians in order to dissuade Americans from spreading west of the Appalachians. Post-war economic issues even strained America’s relationship with their ally, France. The French demanded repayment for war debts and restricted American trade at some of their busiest ports. A stronger central government in America may have resolved these foreign policy and commerce issues, but the Continental Congress did not have the power to intervene. Copyright © 2004 The Regents Of The University Of California