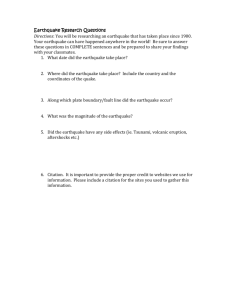

Earthquake Insurance Methodologies and Their Application to

advertisement

Earthquake Insurance Methodologies and Their Application to Energy Supply System Zifa Wang Institute of Engineering Mechanics, Harbin, China, 150080 Abstract: The methodology framework of earthquake insurance is proposed. The framework is composed of four parts: hazard, vulnerability, exposure, and decisions. The methodology for estimating the effect of every part is described. Uncertainty is listed as top issue in the framework and its impact is also studied. The characteristics of energy supply system are considered in the methodology of earthquake insurance. 1.Introduction Earthquake insurance was a profitable business before the 1994 Northridge Earthquake in the United States. Even with 500 million dollars loss from the Loma Prieta Earthquake in 1989, the loss was still below the industry profit for that year (Allied Brokers, 2003). The 1994 Northridge Earthquake shocked the insurance industry with its 30 billion loss, and resulted in the bankruptcy of a number of insurances companies writing policies in Southern California. Ever since then, the demand is getting higher for the earthquake insurance and services surrounding the insurance. A number of companies in the service sector, such RMS Inc (http://ww.rms.com), have seen their business grown in leaps and bounds. In Japan, earthquake insurance is partly supported by the government, but insurance companies have gradually understood the importance of engineering knowledge in helping their business. Oyo-RMS Inc. (http://www.oyorms.co.jp) has been leading the work to transform the knowledge in RMS to the Japanese market, and its business has grown significantly in recent years. In China, although the responsibility of earthquake insurance was noted in fire insurance as early as in 1951, there was no research work associated with earthquake insurance. In 1996, People’s Bank of China excluded earthquake insurance in its basic insurance policy, recognizing the disastrous consequences of huge earthquakes. In 1997, some preliminary research work was conducted in the Geophysical Institute, China Seismological Bureau, under the support of People’s Bank of China and China Seismological Bureau. With the entry into WTO, China as well as foreign companies investing in China has understood the importance of earthquake insurance. The government has started the preparation work to initiate a formal policy for earthquake insurance. Even with over 10 years of research history in the United States, there is still more to be understood than what is already understood. There are a number of areas that need further study, including the probability of earthquake occurrence, the vulnerability of buildings, and the loss estimation given the occurrence of an earthquake and a building type. This article will try to formulate around this line of thinking and derive a useful form of framework which can be applied directly in the earthquake insurance industry 1 S1-2 2.The methodologies The fundamental problem for an earthquake insurance company is to estimate as accurate as possible its average annual loss due to earthquakes. In theory, this can be formulated as AAL = sum (Loss * Rate ) (1) where loss is the damage amount for a given earthquake, and the rate is the occurrence probability for that earthquake. The summation is over all the possible earthquakes around the point of consideration. The rate of occurrence can be derived from the historical earthquake catalogue given the earthquake source definition. The earthquake source definition is based on the study of geological information with help of information from earthquake history. A typical relationship between the rate of occurrence and earthquake magnitude can be expressed as log N = a + b * M (2) where N is the number of earthquakes, a and b are parameters, and M is the magnitude. Parameters a and b are calculated based on the analysis on earthquake catalogue. The loss in (1) can be expressed as Loss = f(H, V, E ) (3) where H here stands for earthquake hazard, V stands for vulnerability, and E stands for exposure. Hazard here is that caused by the occurrence of an earthquake. In most cases, it is expressed in MMI, ranging from 1~12, where damage usually occurs where MMI is over 6. In recent years, the uncertainty of MMI has been listed as one of the top reasons why researchers need to find a better parameter. Response spectrum appears to be one of the top candidates. The main advantage of introducing response spectrum is its quantitative nature and its variation over different periods. With response spectrum, the work to estimate the loss amount for a given hazard becomes simpler, but the estimation of response spectrum itself from an earthquake becomes more difficult. In other words, introduction of response spectrum shifts the problem from behind the hazard to before it in the loss estimation process. More research needs to be conducted to find a better solution or to reduce the difficulty of response spectrum estimation. Vulnerability is another factor in the process of defining the loss. Vulnerability is defined as the potential of loss occurring given the hazard. In others words, given MMI or earthquake response spectrum, what is the possibility of occurring total loss and what is the damage if there is any? Vulnerability is closely related to hazard, as well as the type of structures. As demonstrated in previous researches, the material and its quality in buildings determine mostly the damage of them in an earthquake. The details of structure design and its shape will also make good differences in vulnerability. A good shaped building and a nicely designed structure certainly pay off in an earthquake event. Building age also plays an important role in determining its vulnerability. The older a building, the more vulnerable it will be. There are at least two reasons why age plays an important role. First, with the increment of age, the quality of building materials will deteriorate. Second, the design code and standard have progressed with time. The newer the building is, the higher the design standard. Exposure is defined as the structures or buildings exposed to the risk of earthquakes. In almost all the cases, it is composed of the following: 1) the location, 2) the local conditions, 3) building 2 S1-2 information, and 4) the value of the structure. Location information is usually obtained via GIS, and can be decoded in GIS system given the latitude and longitude of the location. The local conditions basically contain soil and other site information around the building and structure such as topography. Building information usually provides what needed to be used in vulnerability, like building type, design details, and age of the building. The value of the building usually stands for the replacement cost, that is, the total amount needed to rebuild the building. The cost of land usually does not get included in the calculation. In certain extreme cases where land becomes unusable due to earthquake damage, its cost will also be included. When AAL is calculated, it is now easy to derive the pricing for the insurance industry, which is Premium = AAL + Oscillation + Admin Cost + Profit (4) where premium is the amount the insurance companies charge their clients. Oscillation is the amount extra needed to account for variation of loss from earthquakes. It is caused by the uncertainty of the loss, which we will discuss in the next section. Oscillation is usually in linear relationship to standard deviation of the average annual loss, with linear factor ranging from 20% to as high as 100%. Administration cost is the amount needed to administer the policies in earthquake insurance and profit is the amount needed to satisfy the business profit desire from earthquake insurance companies. There are other kinds of formulae to derive the premium of insurance policies, but they all share the following common thoughts. 1) They are also based on AAL or average loss; 2) They all consider the extra parameter (oscillation) to mitigate the risk; 3) They all consider profit in determining the premium. The last part in the whole chain is the decision. In order to make decisions, another step is needed to calculate the net insurance loss given a policy. A policy is usually composed of a deductible, a limit and a sharing percentage (participation factor). There are two problems here. One is the calculation of a single policy and the other is the aggregation of multiple policies to form a portfolio. Many decisions are made based on the analysis on the portfolio level, rather than at the single policy level. On a single policy level, the higher the deductible is, the lower the premium is. The higher the limit is, the higher the premium will be. The higher the sharing percentage, the higher the premium will be. The aggregation of loss for a portfolio will be the simple summation of losses from all the policies. On the portfolio level, reinsurance is often introduced to cover the risk of huge earthquake loss event. Another factor that might affect the decision is the probable maximum loss (PML). This parameter is very important in that it describes the loss amount in extreme cases, which serves as a foundation on a decision process because this is the amount which could be the maximum loss the insurance company will incur should a big earthquake occurs. Historically, the loss amount for worst-case scenario is used to approximate PML. Unfortunately, due to unknown nature of earthquakes and the short history of our catalogue, future PML could in theory surpass the loss amount based on worst-case scenario. A good extension is to calculate the PML value from the curve of exceeding probability of earthquake event. Given the occurrence rate, loss and standard deviation for every event, assuming that there is no correlation among earthquake events, it is easy to calculate exceeding probability as (Dong, 2002) Prob (Loss >= loss-d) = 1 – Prob (Loss < loss-d) = 1 – exp (-sum(rate)) (5) 3 S1-2 where loss-d is the loss amount for event d, rate is the occurrence rate for event d. From equation (5), it is straightforward to derive the curve for exceeding probability. The good thing about this curve is that we can derive any loss amount given the probability value. For example, the loss amount corresponding to 1% on the exceeding probability curve means that there is a 1% chance that the loss amount will surpass the amount given from the curve. 3.Uncertainty In the methodologies section, we mentioned a number of the times the word “uncertainty”. In this section, we will concentrate on what is uncertainty, why it occurs, and how to deal with it. The uncertainty appears because of the following. 1) The uncertainty appears in source definition. Earthquake occurs underneath the earth surface. Even with the most advanced survey technology, we still know very little about the earthquake surface, even less about what lies underneath the surface. Therefore, we are not sure about the exact location of an earthquake occurrence. 2) We are unsure about when and how often the earthquake will occur. Earthquake only occurs at a given source very infrequently. In places with close to a thousand years of catalogue history, the confidence of exactly determining the earthquake occurrence is still very low. For example, “Tokai Earthquake” was predicted to happen in the early 1970s, but it has not happened yet in the year 2003. There was nothing predicted near the Kobe area, yet the Great Hanshin Earthquake occurred in 1995, resulting in the biggest loss in history. 3) There is also uncertainly in determining the vulnerability, either in forms of uncertainty of MMI determination or in forms of defining building information. Given all the necessary information on buildings, it is still not easy to decide the vulnerability. 4) The uncertainty in exposure definition in terms of site information and others. Hazard uncertainty is usually considered in the form of the rate of occurrence. This rate is in the form of probability, to include some form of uncertainty. The uncertainty of vulnerability is considered in the form of variation associated with a vulnerability curve. The exposure uncertainty is ignored here because most part of it could be minimized via detailed site investigation and information gathering. Therefore, we will focus on the uncertainty of vulnerability, hence the standard deviation of vulnerability. Furthermore, the uncertainty of vulnerability results in the uncertainty of the loss estimation. Assume that each event is an independent Poisson process, that is, it does not have memory in time series and it does not correlate spatially with other events, the standard deviation of loss can be expressed as SD = SQRT (Sum(SD-Event* SD-Event*Rate)) (6) where SD-event is the standard deviation for any given event. Given SD and Loss, with the assumption of certain distribution type, it is possible to derive the loss for any given policy on a probabilistic basis. Beta distribution is usually used in the calculation (Dong, 2002). 4 S1-2 4.Vulnerability of Energy Supply System Essentially, there is no fundamental issue in applying the proposed framework to energy supply system. There are a few special areas that need extra attention. One is the impact of indirect loss. Indirect loss is defined as the subsequent loss due to the damage to the energy supply system. Typical indirect loss includes economic loss, business interruption, and extra cost to cover the non-functioning of the energy supply system. Compared with other building structures, the higher the damage is, the more impact the indirect loss will have. In extreme cases, the ratio of indirect loss to direct loss could be as high as 12. The main reason behind this phenomenon is its networking nature. In other words, if there is damage to a part of a lifeline system, the damage is not only applied to the part that bears the direct damage, it is also affecting other parts in the system due to the fact that the damaged part is a portion of the whole system. Take the gas supply system as an example; if there is any damage to the main pipeline, all the users along the downstream will be affected. If there are any plants depending on the supply of this pipeline, its production line will have to be stopped and this will result in extra business loss, which is part of indirect loss. Another character of energy supply system is that it spans over a long distance, easily crossing lands of hundreds of kilometers. Unlike regular buildings with only a few hundred meters of span, the large spans of the energy supply system is subject to variable input of earthquake excitation. The propagation effect of seismic waves has to be considered to account for this large span issue. At this time, there is no effective method to satisfactorily estimate the vulnerability of the energy supply system. There are two lines of thinking we can use here. One is the concept of discrete system. In the discrete system, every tower and every plant of transition could be considered as an independent element. Seismic analysis on the single component is performed to derive the vulnerability for the element, and the loss of the whole system is aggregated through consideration of correction factors to account for the dependent nature of components within the system. Another method is to treat the whole system as a whole via network theory. Shinozuka etc. (1983) studied the reliability of the whole system based on networking concept with the help of structural analysis. Recently, with the development of grid theory, a few beams of new light have appeared on the other end of the tunnel. It is very possible to apply the grid theory for computing via the world wild web to consider the seismic response and reliability of the whole system, thus deriving the vulnerability for the whole system. Even with the grid theory, seismic analysis of every single component is still the basis for the whole system. Recent advances in high-power computing make it possible to put the whole system inside our computational range. This will further solidify the foundation on which to build our vulnerability curve for the energy supply system. Further research is inevitable to make it possible. 5.Conclusion A framework for earthquake insurance is proposed here. Every component in the framework is discussed in detail. Uncertainty in the process, especially that of vulnerability in the form of standard deviation, is discussed. The method of insurance premium calculation is also studied 5 S1-2 based on the framework proposed in this article. Finally, special attention is give to energy supply system in calculating earthquake loss and insurance premium. 6.References Allied Brokers (2003), California Earthquake Authority: Why Pay? http://www.alliedbrokers.com/earthquake2.html Dong, W.M. (2002), Engineering models for catastrophe risk and their application to insurance, Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Vibration, 1(1), 145-151. Huang W.Q. and Wu X. (2002), The Effect of Uncertainty of Seismicity Parameters on Risk Estimation for Large Cities, Earthquake Engineering and Hazard Mitigation, Earthquake Press, 191-196. Huo, J.R. (2002), A Summary on the Development of Risk Management in Foreign Countries, Earthquake Engineering and Hazard Mitigation, Earthquake Press, 197-205. Shinozuka, M. and Benaraya, H. (1983), Seismic reliability of telecommunications networks, PVP, Vol.77, ASME, 433~443. Ying Z. Q. (2002), Building Damage Assessment and Its Research in China, Earthquake Engineering and Hazard Mitigation, Earthquake Press, 543-549. Yuan, Y.F. (2002), Investigation on loss estimation of natural hazards, Institute of Engineering Mechanics. Zuo H.Q. (2002), Earthquake Loss Estimation Model and Earthquake Insurance, Earthquake Engineering and Hazard Mitigation, Earthquake Press, 700-705. 6 S1-2