A Hebrew Understanding - The Wesley Center Online

advertisement

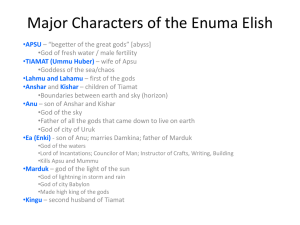

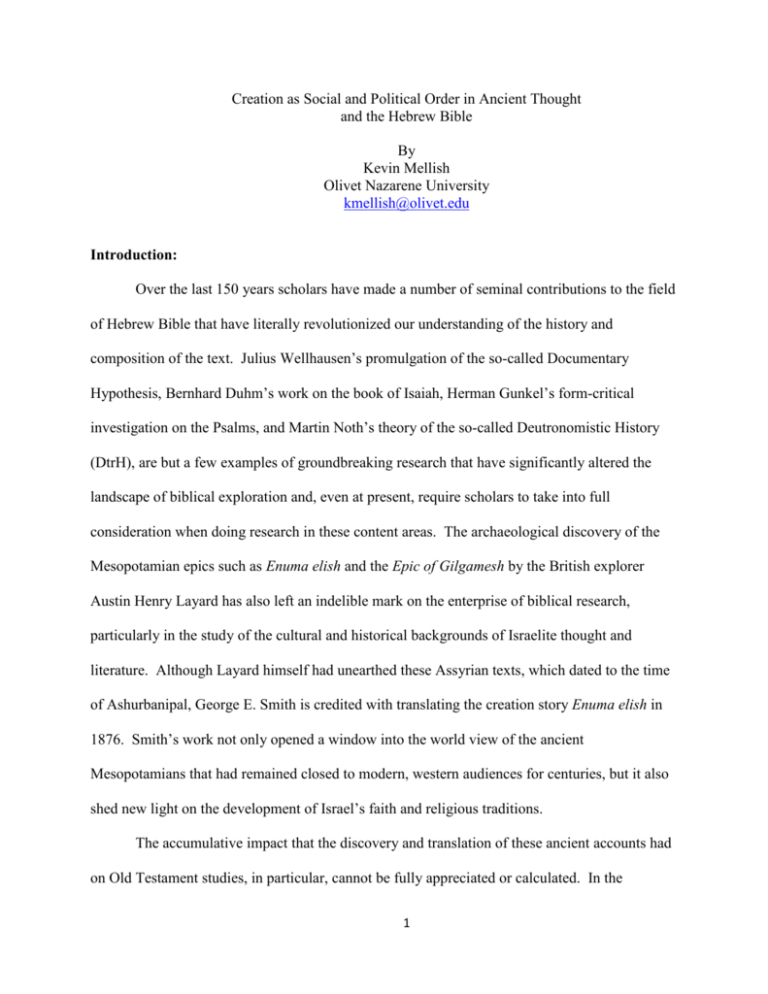

Creation as Social and Political Order in Ancient Thought and the Hebrew Bible By Kevin Mellish Olivet Nazarene University kmellish@olivet.edu Introduction: Over the last 150 years scholars have made a number of seminal contributions to the field of Hebrew Bible that have literally revolutionized our understanding of the history and composition of the text. Julius Wellhausen’s promulgation of the so-called Documentary Hypothesis, Bernhard Duhm’s work on the book of Isaiah, Herman Gunkel’s form-critical investigation on the Psalms, and Martin Noth’s theory of the so-called Deutronomistic History (DtrH), are but a few examples of groundbreaking research that have significantly altered the landscape of biblical exploration and, even at present, require scholars to take into full consideration when doing research in these content areas. The archaeological discovery of the Mesopotamian epics such as Enuma elish and the Epic of Gilgamesh by the British explorer Austin Henry Layard has also left an indelible mark on the enterprise of biblical research, particularly in the study of the cultural and historical backgrounds of Israelite thought and literature. Although Layard himself had unearthed these Assyrian texts, which dated to the time of Ashurbanipal, George E. Smith is credited with translating the creation story Enuma elish in 1876. Smith’s work not only opened a window into the world view of the ancient Mesopotamians that had remained closed to modern, western audiences for centuries, but it also shed new light on the development of Israel’s faith and religious traditions. The accumulative impact that the discovery and translation of these ancient accounts had on Old Testament studies, in particular, cannot be fully appreciated or calculated. In the 1 aftermath of their translation, biblical scholars at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries were smitten, even enraptured, with the prospect of analyzing and interpreting the great creation texts of the Hebrew Bible (Gen.1-3, for instance) in light of the newly translated myths from Mesopotamia as well as those from Rash Shamra and Egypt. Initial examination of these ancient Near Eastern texts revealed that the creation myths from Mesopotamia contained some of the closest literary and thematic parallels with the Genesis traditions, and thus, detailed comparison/contrast analysis between the biblical materials and works such as Enuma elish, Gilgamesh, and Atrahasis followed in earnest. Concomitantly, the development of the Documentary Hypothesis provided scholars a chronological framework by which to date texts like Genesis 1-3 against the creation epics of the ancient Near East. According to source critics like Wellhausen, Genesis 1:1-2:4a derived from priestly circles and could be dated to the exilic or even post-exilic period. As a result, modern critical scholars posited that Gen. 1:1-2:4a was a younger tradition than the Mesopotamian epics and thus any similarities between the Genesis material and Mesopotamian accounts suggested that the biblical writers borrowed language and ideas from the latter. Trends within the discipline of Old Testament theology at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century had also progressed to the point to where it became methodologically fashionable to incorporate the study of the biblical creation narratives within the History of Religions (Religionsgeschicte) School. Robert A. Oden notes of this period that, “the larger program of the “History of Religion School” was most basically founded on the project of fully utilizing texts from outside the OT to explain the development of the OT” (1992, 957). Thus, scholars associated with the History of Religions School consistently examined and evaluated biblical texts in light of the ancient literature and religions of the world, which in the 2 end, tended to emphasize the similarities between Israel and her neighbors rather than illuminating the distinctive elements of Israel’s thought and theology. No scholar exemplified the above mentioned approach more than Herman Gunkel, the father of form-critical methodology and a pioneer in comparative religions. In his monumental study, Creation and Chaos in the Primeval Era and the Eschaton (Shopfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit), Gunkel set forth to systematically flesh out elements of the creation narrative in Gen. 1 which had direct parallels with the Mesopotamian creation stories. As a result of his detailed analysis, Gunkel argued that it was impossible for a text like Gen. 1 to have originated independently in an Israelite context, but, at its most primal level, owed its existence to Mesopotamian lore. To prove his point, Gunkel methodically analyzed the theme of chaos war (Chaoskampf) in creation myth and argued that it was an ancient concept that had been co-opted and later demythologized by the writers/narrators of Gen. 1. At the conclusion of his investigation, Gunkel wrote, “From this it follows that Genesis 1 is not the free composition of an author but it is rather the deposit of a tradition. Furthermore, this tradition must stretch back to high antiquity” (1984, 31). For many practitioners of the History of Religions School there was nothing really new in the Old Testament that was not a pale reflection of Babylonian thought. Fredrick Deilitzsch even argued that the Old Testament was lacking almost completely in originality. One can see a strong backlash to this position in the work of Gerhard F. Hasel, for instance. Hasel, in particular, attempted to show that the creation narratives in the Old Testament were not as similar to Babylonian creation mythology as those in the History of Religion School had maintained. Hasel argued vehemently that the cosmology of Gen. 1 exhibited a sharply anti-mythical polemic. He wrote, “It appears that Genesis cosmology represents not only a “complete break” with the ancient Near Eastern mythological cosmologies 3 but represents a parting of the spiritual ways brought about by a conscious and deliberate antimythical polemic which meant an undermining of the prevailing mythological cosmologies” (1974, 91). Whether Hasel is completely correct in his assessment of these issues remains up for debate, but it is more important to note that his reaction to the pan-Babylonian approach of scholars like Gunkel demonstrates the extent to which modern researchers had assumed Mesopotamian influence on the biblical text. Scholars of the Old Testament will remain indebted to those who discovered and translated these ancient accounts and pointed out where the biblical writers were familiar with their content and even borrowed from them when composing texts like Gen. 1-3. The purpose of this paper, however, is not to engage again in a systematic comparison/contrast analysis showing where the creation accounts of the Bible have literary and thematic points of contact with ancient Near Eastern mythology as well as significant differences. As the previous paragraphs have attempted to show, this type of investigation has been done satisfactorily by people much more competent than me and the research on this topic is extensive (see Westermann for bibliography). Rather, the thrust of this examination will focus on the connection between the creation accounts themselves and the historical contexts in which they were written. In so doing it will become evident that on one level creation narratives reflected the social and political realities of the societies that produced them as much as they attempted to explain the origins of the cosmos and the earth. The connection between the creation accounts of ancient societies and their historical context is evident in two ways. First, creation narratives functioned as etiologies in the ancient world and thus explained phenomena characteristic of the natural world and human society. Second, ancient cultures depicted the defeat of primordial chaos at creation as resulting 4 in the establishment of social and political order. As we will see, both of these concepts are particularly relevant in ancient Mesopotamian and Hebrew thought. Creation Narrative as Etiology: In addition to serving religious or metaphysical purposes in the ancient world, mythology, in general, and creation myth, in particular, inherently touched on issues pertaining to the mundane or secular aspects of human existence. Creation narratives possessed the unique ability to provide justifiable causes for the most common experiences of life. Biblical scholars, ancient historians, and anthropologists alike have long known that at the physical level creation narratives could serve as explanations for certain social or natural phenomena in a society. That is to say people who have studied ancient cultures and literature have recognized creation myths could function in an etiological capacity. In referring to the function of myth in an ancient society Oden says, “myths reflect both a particular stage in human development and the universal and continuing need for humans to explain things” (1992, 950). By functioning as etiologies, creation narratives were able to assign a specific cause or rationale for the origin of a people, the domination of one group over another, the differences between ethnic groups or the sexes, and even the practice of certain customs or the establishment of particular mores in a society. Joan O’Brien Wilfred Major has shown, for example, how certain elements within the Atrahasis poem contain explanations for the origin of certain rituals related to childbirth in Mesopotamian society (1982, 73). Likewise, Tikva Frymer-Kensky and others have demonstrated how in Atrahasis the introduction of death, the creation of female sterility, miscarriages, and religious celibacy serve a useful function in that they limit human population and obviate the need for the gods to destroy the human race (1977, 36). The Akkadian myth, A 5 Cosmological Incantation: The Worm and the Toothache, performs a similar explanatory duty by linking the cause of toothaches to a worm that the gods had allowed to dwell among the teeth and gums (ANET 100-101). Likewise, African creation narratives from Tanzania and Zambia account for the separate origins of men and women through etiology as well as explain the unique differences which exist between the sexes (Van Wolde 1995, 219-228). In many respects, Israel’s creation narratives were no different than other ancient peoples in that they also contained etiological elements within them. These narratives not only touched on cosmological or metaphysical issues and/or justified the superiority of Yahweh/Elohim over against the gods of her neighbors, but they also served as a means to explain certain historical realities endemic to a Syrio-Palestinian environment. Tradition-history scholars, such as Sigmund Mowinckel along with Gerhard von Rad and Martin Noth, had long been interested in the historical development of traditions which dealt with the origins of countries and nations, the names of cities, sacred or cultic sites/shrines, unique customs and traditions as well as people’s names. At the same time, tradition-history scholars were quick to point out that etiology appeared as an essential component of the creation traditions in Genesis. To prove this point one only has to consider a text like Gen. 2:4b-3 to realize that it abounds with etiological agendas. For example, the term for man, אדם, which is prevalent throughout the narrative, is linguistically related to the word for ground/earth, אדמה. By engaging in a word play that links man with the ground out of which he was fashioned, the biblical writers effectively highlight the fragile, finite nature of human beings who return to the אדמהin death. Also, the text demonstrates how males and females share a basic human identity and bond, since the woman was literally built ( )בנהout of the rib of the man. The Hebrew nomenclature also captures this special human connection by showing that אשהis derived from 6 אש. The story, furthermore, powerfully conveys the harsh realities of life and provides a cause for the tenuous existence of human beings living in Syrio-Palestine. Farmers trying to eke out a living in a part of the world where rain was withheld for long periods of time could surely appreciate the message of the Gen. 3:17-18: Cursed is the ground because of you, you will not eat of it, cursed is the ground because of you in toil you will eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it will bring forth for you; and you will eat of the plants of the field. By the sweat of your face you will eat bread. . . . In the same narrative complex, explanations are also provided for the misfortunes the woman has to endure. Trying to make sense of the extremely painful experience of childbirth certainly provided the impetus for the ominous words uttered in Gen. 3:16 which read, “in pain you will give birth to children (in Hebrew the word is sons).” In the minds of the biblical writers the acute pain and stress associated with childbearing seemed to be a curse a woman had to suffer, and they explained this agonizing experience in a manner that did not incriminate God but placed the onus for the woman’s travails on human misconduct. Similarly, the creation story in Gen. 2:4b-3 explains the women’s subordinate role to her husband in Israelite society through the use of etiology. According to Pyllis Trible, the account of Gen. 2-3 shows that the narrative does not proclaim male domination and female subordination as the true will of God; rather, it is the result of a curse. Moreover, she contends that the statement, “your desire is for your man, but he will rule over you,” actually judges the patriarchy of Israel as a sin (1992, 405) (what a commentary about Israelite social patterns!). The text also has something interesting to say about more trivial matters, such as the nature and destiny of serpents. The biblical writers creatively (pardon the pun) explained the 7 reason why snakes slithered on the ground and posed a threat to human beings. Here, the text justifies the permanent abasement of serpents, which are destined to crawl on their bellies in the dust, as a curse and appropriate punishment for the role the first serpent played in tricking the women into eating the fruit. The power of this etiology is reinforced by paronomasia so that the woman’s response to God, in which she exclaims the serpent tricked her, sounds like the actual hissing of a snake ( )השיאניin Gen. 3:13. Thus in examining a text like Gen. 2:4b-3, it becomes clear that creation narratives could function in a manner that explained present-day historical realities. According to the ancient mind, such phenomena existed since the beginning of time (at the time of creation) and they continued to remain in existence even after these traditions had been committed to writing. Creation as Social and Political Order in Mesopotamia: While creation narratives could function as etiology in an ancient context, they were just as much concerned with the development and subsequent organization of human society. In an important article entitled, “The Hebrew Scriptures and the Theology of Creation,” Richard J. Clifford draws attention to this fact by delineating the major difference between ancient and modern understandings of creation. He says, “modern common-sense definitions of creation are inadequate for the biblical texts; they read back into ancient documents the modern spirit shaped by scientific and evolutionary thinking” (1985, 508-509). In this article, Clifford draws four main differences between the ancient West Semitic and modern concept of creation in terms of the process, the emergent, the description, and the criteria for the truth. It is Clifford’s attention to the outcome of creation, or that of the emergent, which has the most relevance for the topic at hand. He notes that in the mind of the ancient audience the 8 emergent that resulted from the creation process included human society organized in a particular place. In contradistinction, he argues that in the modern mind creation issues in the physical world, typically the planet fixed in the solar system. He maintains that the development of community and culture does not come into consideration when scientists wrestle with a physical understanding of the origins of the universe (1985, 509). In this regard he also echoes the sentiments of H.H. Schmid who noted that creation faith within the ancient Near East did not deal only, “indeed not even primarily,” with the origins of the world; rather it was concerned with the present, natural environment of humanity now (1984, 104). He notes that this is evident particularly in the way ancients viewed the emerging social and political order that resulted from the deity’s battle with primordial chaos in creation. In the ancient world, the defeat of chaos not only resulted in an ordered creation and provided assurance for the renewal of nature, which led to yearly rituals celebrating this victory, but it also eventuated in the ordering of the political state itself. Thus, it should come as no surprise that the battle against chaos not only appears in cosmological contexts but it comes up just as frequently in political contexts as well. Clifford and Schmid’s understanding of the emergence of human society and the political state, as it relates to the creation process, finds a home in the Mesopotamian epic, Enuma elish. On one level, the mythic level, the story of Enuma elish essentially contains a theogony, a cosmogony, and a story of succession among the gods. To be brief, I acquiesce to the fine analysis of O’Brien Wilford Major and summarize her work on these particular points. She notes, first of all, that in terms of Enuma’s theogony each new generation of gods that is created surpasses its elders in wisdom, strength and personality. The early gods are limited by the natural phenomena they represent, but the later generations of gods are not so closely tied to natural phenomena by acting in more human ways (1982, 12). Although Enuma elish includes a 9 cosmogony, she notes that it is a rather incomplete one. It does not include the creation of plants and animals or other important creatures. Rather, it emphasizes the process of creation rather than results (1982, 12). She observes that creation in the poem happens through sexual regeneration, as in the case of the gods themselves, as well as through divine craftsmanship, such as when Marduk fashions human beings into existence. Thus in Enuma elish two different views of the creation of the world are apparent. First, in the genealogy which begins the poem, we see the world is formed naturally as the gods breed new generations of themselves. Of this view she notes, “the world is virtually a living being, divine and constantly expanding” (1982, 13). In the second view of creation, personal deities create things at will for their own purposes. She writes, “These gods do not follow any unified plan, nor do they worry about the conflict which their new creation may cause” (1982, 13). In examining this situation, she argues that the two distinct portrayals of creation in the epic suggest a chaotic and unpredictable universe. She comments that, “There is no necessary end to the process of creation, no permanent resolution of the inevitable conflicts which result from continual formation of new parts of the world. Within this context, the theme of royal succession emerges as the most important element” (1982, 13). What emerges from this scenario is an unpredictable world, one that needs stability and control; however, such order is lacking until Marduk assumes the powers of kingship over all the gods. Prior to Marduk’s ascendency and installation as the divine king, the gods are basically divided into two camps. The older gods, headed by Tiamat, are passive and dislike change. The younger generation, which is led by Anu, is noisy, disorderly, and always active (1982, 14). As a result of the personality conflicts and generational divide, a full scale war inevitably breaks out between the two groups. Anu seeks the help of Marduk who later harnesses the four winds, a bow and quiver, a sword, 10 lightning, and a net to battle and capture Tiamat. Once Tiamat is contained in this battle, Marduk takes a mace and clubs Tiamat over the head and later cuts her body into two parts. In return for defeating Tiamat and her minions, Marduk first of all requires (3:116-122) and subsequently receives absolute control as king over the world of the gods and human beings. For his efforts, the gods erect a princely throne for him (4:1), they grant him kingship over the universe (4:14), and joyfully make the grand announcement that “Marduk is king!” (4:28). As the undisputed king over the universe, Marduk subsequently sets out to create the sky, the earth, and the human race. But, more importantly, Marduk uses his power to establish a lasting order among the younger generation of gods. He assigns them each their own planet or star from which they can use their energies constructively. Through these maneuvers, Marduk successfully deals with the conflict among the gods which would otherwise threaten his reign and the stability of the world. The gods now work harmoniously with one another in a wellordered cosmos. In the later sections of the epic, particularly tablets 6 and 7, the act of organizing also includes Babylonian society. Men and women are created to serve the gods (6:58, 29-37, 106-120), while Marduk is worshiped as the chief deity in the temple at Babylon. At the end of the poem, Marduk is bestowed 50 names by the other gods which glorify his role in sustaining order and life on earth and in the heavens (6:121-7:144). Thus, in reviewing these events, Enuma elish can be seen as a resolution of conflict between chaos and order which, according to Barbara C. Sproul and Raymond Van Over, is a prominent theme in many creation stories worldwide. From this standpoint, Tiamat and her followers function as representatives of chaos who threaten the celestial order. Marduk, who symbolizes the guarantor of cosmic order, confronts and defeats these menacing forces which results in a stabilized universe, organization among the gods, creation of sky and earth, and a 11 structured human population which worships Marduk. On another level, however, the appearance of the forces of chaos which threaten the stability of the cosmic realm and Marduk’s ability to quell these foes, in many respects, reflects the social and political threats of Mesopotamian society of the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC and the need for strong centralized leadership to confront them. The poem, therefore, not only recounts events which take place in the cosmos at the time of creation, but it also has much to say about Mesopotamian culture and society prior to and at the time of Enuma’s conception. Thorkild Jacobsen in his book, The Treasures of Darkenss, describes the kind of historical and political forces of the 3rd millennium BC which are apparent in the storyline of Enuma elish. To be brief, he notes that a shift in social threats occurred at the beginning of the 3rd millennium in Mesopotamian society. Unlike the previous era when the threat of famine no longer hounded humans, the potential to be killed by the sword and marauding bandits became the new reality. Whereas the 4th millennium remained relatively peaceful the promise of constant wars and raids became the order of the day in the next (1976, 77). The quickness with which enemies could strike made life uncertain and insecure to say the least. The intensity of this danger can be measured by the construction of enormous city walls which surrounded every city, and the noticeable change in settlement patterns, from small village to fortified city, reaffirms the changing social and political climate as the general population sought protection behind these walls (Khurt 1995, 1:31-32; Van de Mieroop 2004, 43-47). Amid these dangers individuals looked for protection from the important institutions of collective security, and in particular, to the new institution of kingship as it took shape in these years. Kingship, which had originally been a temporary office when war threatened but ceased to exercise authority once the emergency was over, became more prevalent in the face of chronic emergencies later resulting in 12 the permanent establishment of the king, along with his army and the manning and maintenance of the city wall (Jacobsen 1976, 78; Lambert 1964, ). In the midst of these military and political tensions a new savior-figure had come into being, the ruler: “exalted above men, fearsome as a warrior, awesome in the power at his command” (Jacobsen 1976, 79). With regard to the elevation of the public status of the king Jacobsen writes: In the small, tight-knight society of the village and small town, there had not been much social differentiation between people, and not much opportunity for feelings of awe and reverence to develop. With the concentration of power in the person of the king, the experience of awe and majesty entered everyday existence. The unique energy that the king represented was new. His was the central will of society in peace and in war; he was the driving force in all things (1976, 79-80). Jacobson notes that in light of the new historical and political developments during the 3rd millennium, the Mesopotamians projected their conceptions of their deities in terms of political metaphor; namely in terms of the polis, the king, and primitive democratic government. In this model, prominent deities took on the role of divine rulers who were referred to as “master,” “lord,” and “warrior.” He remarks that, “The new view of the gods as rulers brought the whole political context of the ruler to bear on them and thus – since they were the powers in all the significant phenomena around – on the whole phenomenal world. The universe became a polity” (1976, 81). Furthermore, other gods were depicted as manorial lords who oversaw the care and management of temple estates as well as the preservation of order in the towns and villages. In addition, the gods of these manors also held cosmic offices and were entrusted by the higher ranking gods to perform certain agricultural, civil, and judicial duties (i.e. providing rain, assuring justice, inspecting canals, etc.). Moreover, the gods themselves took part in the divine assembly when offering proposals and/or making important decisions. Decisions in the 13 assembly usually consisted of passing judgment on wrongdoers and members could elect or depose officers such as kings. Thus, the Mesopotamians’ conception of their deities in the 3rd millennium coincided with the development of the city-state, the emergence of the king, and the associated political offices of a primitive democracy. Thus, one can see how the events in the Enuma elish epic reflect the changing historical circumstances and political conditions in Mesopotamian society in the previous millennium. The major theme and plotline of Enuma – anarchy and revolt, confrontation and defeat of an intimidating threat, the securing and preservation of order, the election and exaltation of the king - accurately depicts the social and political conditions which gave rise to the Mesopotamian ruler (see especially Jacobson’s chart on p. 184 which illustrates the journey in the epic from anarchy to monarchy). In looking at the epic many parallels between Marduk and the Mesopotamian king come to light. Marduk was made king at a time of crisis, the Mesopotamian king became the unquestioned ruler in war. The gods looked to Marduk to confront the cosmic forces of chaos, the people looked to the king to face military threats. Marduk established order and harmony in the cosmos, the king preserved stability and justice on earth. While the 3rd millennium provides the general background conditions which are reflected in the epic, W.G. Lambert notes that the exaltation of Marduk as well as the city of Babylon in the poem most likely situates its Sitz im Leben at the time of Nebuchadnezzar I. This poem represents the resurgence of Babylonian society after being defeated by the Assyrians a century earlier. It is a celebration of Nebuchadnezzar I’s military triumph over Elam and the political restoration of Babylonian power in the region. It also represents a significant religious victory since Nebuchadnezzar returned Marduk’s statue to the Babylonian temple and thus reestablished his prestige among the gods (1964, 10). In this epic, therefore, one can see the intimate 14 connection between the metaphysical world of Enuma and the historical conditions of ancient Mesopotamian society. Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon, successfully defeated his enemies and restored religious and political order to Babylonian society as Marduk does in Enuma. However, the epic remained fluid in its transmission over time and thus it could be adapted to fit the conditions of a changing political landscape. This can be detected in the early part of the first millennium when the Assyrians replaced the Babylonians as the major power in the region. In this new historical context, Ashur replaced Marduk as the main hero of the tale. Creation as Social and Political Order Within the Hebrew Bible: The relationship between creation, social order and political organization was not simply limited to ancient Mesopotamian culture. The emergence of human community, even the people called Israel, subsequent to the deity’s battle with the forces of chaos is found within the pages of the Hebrew Bible. P’s account of creation in Gen. 1:1-2:4a exemplifies this notion. Here, Elohim not only confronts the forces of chaos – the void ()תהו, the darkness ()חשך, and the sea ( – )יםand defeats them, but humanity emerges as the culminating achievement of the creation process. In Gen. 1:26-28, man and woman are created in the image of God and they are also commanded to be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth. It is presumed from this context that human interaction and cooperation are needed in order to fulfill this divine mandate, both at the personal and community level. Whereas P is general in its description of the creation of human community, other sections of the Hebrew Bible associate creation with the emergence of the people of Israel. In this case, however, Israel’s creation is linked with the Exodus tradition and the liberation from Egyptian bondage, not with a cosmological text like Gen. 1:1-2:4a. The poetic text of Exod. 15 15:1-18, also known as the Song of the Sea, vividly describes the event when Yahweh redeemed his people. Cited as one of the earliest pieces of Israelite literature, and reminiscent of Ugaritic literature in poetic style and literary structure (Cross, 1973, 121-123), a number of scholars have noted that this text echoes the ancient theme of the Chaoskampf inherent in Mesopotamia and Ugaritic literature (Brueggeman 1994, 799-802; Propp 1999, 522-523). In this text, it is Yahweh, not Elohim, who appears as the Divine Warrior and engages in the mythical battle with chaos: Yahweh faces and defeats a powerful adversary, Yahweh moves triumphantly to the sacred mountain which serves as his dwelling (temple in Zion), and upon the sacred mountain is acclaimed as the divine Lord forever (Ex. 15:18). Even though Pharaoh and his army are the main antagonists in the poem, the sea, according to Cross, does appear as a “passive instrument in Yahweh’s control” (1973, 131). Throughout the text it is unmistakably clear that the sea and the primordial deeps are at the mercy of Yahweh’s authority. Verse 5, for instance, specifically references the ancient or primordial deeps ( )תחמתwhich Yahweh turns loose for his purpose; that is to cover Pharaoh’s chariots and army. Later, in v. 8a, the waters ( )מיםstand up (at attention) like a wall at the “blast of your nostrils.” The combination of the waters ( )מיםand ruach or wind ( )רוחin this verse is significant, because they are the exact terms used in Gen. 1:2 where Yahweh’s spirit ( )רוחhovers over the primordial waters ()מים. Brueggeman notes of this language, “The poetry here moves well beyond the specific enactment of the Exodus and appeals to the language of the creator’s victory over and administration of chaos” (1994, 800). In v. 8b, the primordial deeps are mentioned again. Whereas in v. 5 Yahweh releases them to overcome Pharaoh’s army, here they are congealed or silenced/stilled once they have served Yahweh’s purposes. Later, verse 10 states, “You blew with your wind, the sea covered them; they sank like lead in the mighty waters.” Again, the connection between the wind ( )רוחand the sea ( )מיםis 16 significant and should not be overlooked. Here Yahweh’s spirit manipulates the waters in order to destroy Israel’s enemies and, according to Brueggeman, this not only recalls a contest between Yahweh and Egypt, but between creation and chaos. In considering this chapter as a whole Umberto Cassuto notes that Yahweh’s victory points to the theme of Chaoskampf because it was “not only a mighty act of the Lord against Pharaoh and his host, but also an act of might against the sea, which was compelled to submit to His will” (1983, 177-178). He further supports this position by showing how the language of this text was interpreted as Chaoskampf in later prophetic and rabbinical tradition. As a result of Yahweh’s actions, therefore, Yahweh not only used the sea to defeat Israel’s enemies, but in the narrative account of the Exodus, it was also parted so that the Israelites could walk through it on dry ground. The deliverance from bondage and the victory at the sea thus served as the backdrop for the initiation into the Mosaic covenant (Ex. 20:2), the time of Israel’s infancy. As mentioned above, there is no suggestion in Ex. 15:1-18 of creation in a cosmic sense, rather, as Bernhard W. Anderson notes, “the emphasis falls upon the coming to be of a people” (1984, 5). The Israelite people would always remember this event, the liberation from Egyptian oppression, as the time when the nation came into existence. The text extols Yahweh, for example, who faithfully led the people he redeemed (Ex. 15:13a). Later, the writer will refer to this time as the moment when God created them: “While your people passed over, Yahweh, the people you created passed by” (Ex. 15:16b). Here, the Hebrew verb qana ( )קנהis utilized which can be rendered ‘to create’ (against the NRSV which reads ‘acquire’) as in Gen. 14:19-20, 22 (see BDB, 888). In Ugaritic literature, Dennis J. McCarthy has demonstrated that this verb displays sexual overtones, as in procreation (1984, 78; TDOT 13:60-61; TWOT 2:804). He notes that this term also contains an endearing quality to it, and thus can be rendered ‘father’ 17 rather than the generic term ‘maker’. It is significant to note that this is the same verb utilized in Deut. 32:6b which states, “Is not Yahweh your Father, who created you, who made you and established you?” Here the biblical writers equate God’s role as creator with that of a father, thus insinuating the people of Israel were his children. Other poetic traditions echo the sentiment of the Mosaic tradition which states Israel had been created by God. Hosea claims, for instance, that the Israelites were formed to be a people through the action of Yahweh, their Maker (8:14). A number of the Psalms could be cited as well. Psalm 100, for example, affirms that Yahweh is Israel’s maker: O give thanks unto Yahweh, for he is good. His love and mercy endures forever. We are the sheep of his pasture. It is he who has made us and not we ourselves . . . . Psalm 95:6-7 reiterates this concept: O come, let us worship and bow down, let us kneel before the Lord, our Maker! For he is our God, and we are the people of his pasture, and the sheep of his hand . . . . The poetry of Second Isaiah refers to Yahweh in these terms. In Isaiah 40-55, for example, Yahweh is called “the Creator of Israel” (43:15), the “one who made you, who formed you in the womb” (44:2a), and the “Holy One of Israel, and its Maker” (45:11). As the biblical writers reflected upon the Exodus event and viewed Yahweh’s battle with the sea as the time when Yahweh created the people of Israel, so also the powers of chaos (such as natural disaster or military catastrophes) had the potential to threaten Israel’s existence as a nation. Nowhere is this theme reiterated more than the communal laments such as in Psalms 44, 74, and 77. In these Psalms, which are exilic in setting, the “community feels itself to be at the brink of extinction as a people in Yahweh’s land; it liturgically remembers the originating act in 18 order to move Yahweh to renew that act today” (Clifford, 1985, 512). In Psalm 77, for example, Israel’s existence is jeopardized in the aftermath of the exile causing the Psalmist to ask, “has his steadfast love ceased forever?” (v. 8a), and again, “has God forgotten to be gracious?” (v. 9a). In response to these rhetorical questions the writer recites, “I will call to mind the deeds of the Lord, I will remember your wonders of old” (v. 11). On the heels of these questions, the writer then recalls both the Chaoskampf theme and Yahweh’s victory at the Red Sea when Yahweh provided redemption for his people. The Psalmist writes, “When the waters saw you, O God, when the waters saw you, they were afraid; the very deep trembled . . . . . Your way was through the sea, your path, through the mighty waters” (vv. 16, 19a). The reference to these critical events of the past provided the writer with a sense of hope that God would help his people in the current threat they were facing. Second Isaiah also spoke to a community that was living in exile. In this context the prophet reminds the people about God’s role in creation and his ability to overcome chaos in 45:18-19: For thus says the Lord, who created the heavens, who formed the earth and made it; he established it; did not create it a chaos, he formed it to be inhabited: I am the Lord and there is no other. I did not speak in secret, in a land of darkness; I did not say to the offspring of Jacob, “Seek me in chaos. . . . .” Later in 51:9-11, the writer again refers to Yahweh’s battle with the forces of chaos as he is attempting to encourage his audience and remind them that God would fulfill his covenant promises to them: Awake, Awake put on strength, O arm of the Lord! Awake as in the days of old, the generations of long ago! Was it not you who cut Rahab in pieces, who pierced the dragon? Was it not you who dried up the sea, the waters of the great deep; who made the depths 19 of the sea a way for the redeemed to cross over? So the ransomed of the Lord will return and come to Zion with singing; everlasting joy shall be upon their heads; they shall obtain joy and gladness and sorrow and sighting shall flee away . . . . In the above text, the writer has combined elements from both the Exodus tradition and Yahweh’s battle against Rahab and the dragon, two beasts who personify chaos (Isa. 30:7; Job 26:12; Isa. 27:1Ezek. 29:3). This text, along with 45:18-19, are set within an exilic context when Yahweh’s people are removed from their land, the Temple has been destroyed, and the Davidic king has been exiled. In essence, they face losing their identity and the possibility of extinction as a people. The reference to God’s mighty deeds in defeating chaos at the time of creation and at the Red Sea reassures the audience that God is capable of recreating the Exodus event and restoring the fortunes of Israel. The prophet refers to the events of creation and the Exodus to remind the audience that Israel will be a restored/recreated community and they will return home to Zion with jubilation. The power and majesty that enabled God to overcome the sea and the mythical beasts in the Chaoskampf will also be able to make a straight path in the wilderness which will lead home (40:3-5). Whereas the Exodus and Mosaic traditions were primarily concerned with the creation of God’s people, the Davidic or royal covenant associated creation with the establishment of political and social order. Anderson notes that the correspondence between the cosmic order and social order is more at home in the Davidic or royal covenant tradition than in the Mosaic tradition (1984, 7). The basis of the relationship between God and the social world was grounded primarily in the election of the Davidic king and the choice of Zion as the dwelling place of Yahweh. In ancient thought, the king stood as a link between the divine and human realms mediating the power of the deity in his city and beyond (Walton, 2006, 278). The same was true with Israelite kingship in that the security, health, and peace of society depended on the 20 cosmic, created order established by Yahweh whose benefits were mediated through the Davidic monarch (Anderson 1984, 8). This cosmic/social nature of the relationship between Yahweh and the Davidic king is central to Psalm 89. Here, the choice of the Davidic king is placed in the context of Yahweh’s battle with the cosmic forces of chaos. Some scholars have tried to show that this Psalm is a composite of fragments of an old hymn (vv. 2-3, 6-19) and later joined to a lament (vv. 39-52), with the joining being smoothed over by the additions of vv. 4-5 and vv. 20-38. However, in Clement’s study on Psalm 89 the author draws upon the work of James M. Ward and J.B. Dumortier to show that the poem can be taken as a unity and thus cosmology and the installment of the Davidic king should be taken together in this context (Clement 1980, 40-47). As mentioned, this Psalm includes a section detailing Yahweh’s power as creator (89:518). Here, Yahweh is depicted as the Divine Warrior who “rules the raging sea,” but, in this context, the text does not refer to the Exodus tradition like the Song of the Sea does. Rather this scene depicts Yahweh’s triumphant battle with Yam and the monster Rahab, the primordial beasts. In the wake of Yahweh’s battle with these enemies there emerges an orderly world that appears in a succession of cosmic pairs: heaven and earth, north and south, the mountains Tabor and Hermon, and finally the celestial throne (v. 14a). The following lines (vv. 15-18) then tell of the procession of the people, presumably to the Temple, celebrating Yahweh’s victory and the creation of the world. On the heels of the report celebrating God’s victory over chaos, the introduction and election of the Davidic king is recounted. Verses 19-37 specifically celebrate the choice and installation of the Davidic king and announce God’s promise to give him victory over his enemies. The last portion of this section includes reassurances of the enduring nature of the 21 promise and of God’s continued faithfulness to the house of David. It is significant that the covenant with the Davidic king is “part and parcel of the same cosmogony” of the previous verses (Clifford 1985, 514). Based on the form and logical flow of this text, the election and appointment of the Davidic king follows the cosmic order established by Yahweh. The strategic placement of the verses intimates something important about the role and function of the Davidic king; namely, God gives the king victory over Israel’s enemies which eventuates in the establishment of social/political order and justice in society. Thus the cosmic order established by Yahweh is extended to Israelite society in the person of the king. In this way, the initiation and establishment of the Davidic covenant resembles the covenant text of 2 Sam. 7. In 2 Sam. 7, Yahweh promises to provide David rest from all his enemies and, as a result, the people will dwell in the land safely. In both Psalm 89 and 2 Sam. 7, therefore, the selection of the Davidic king is secured and political/social order is promised. The special connection between Yahweh, the Davidic king, and creation found their most visible expression on Mt. Zion. Zion, Yahweh’s holy mountain, represented much more than the place where the king and his family resided; it was home to the Temple, the estate or residence of Yahweh. It was the “sacred center where Yahweh established his house and household” (Stager 2000, 37). Mt. Zion was considered the cosmic mountain which linked heaven and earth. This mountain rested on the primordial waters represented by the Gihon Springs. Lawrence Stager notes that the quiet waters emanating from the primordial pool “signified the orderliness and tranquility of God’s creation, on which humans could rely” (2000, 37). The Temple, located in Zion, was not only the place where Yahweh’s presence dwelt it was a microcosm of the cosmos itself, a porthole into the heavens. The Temple represented the ordered universe where Yahweh could take up his rest and enjoy his estate. The Temple courtyard, where abundant palm 22 trees, cedars of Lebanon, cypress, olive and plane trees could be found, served as Yahweh’s personal garden sanctuary (Ps. 52:8; 92:13-14; Ezekiel 31:8-9), and the Gihon springs watered the gardens and parks which cascaded down the terraces of the slopes of the Kidron Valley. From the Jerusalem Temple flowed abundant streams from the “Fountain of Life” (Ps. 36:8-9). Stager notes that these waters symbolized the life-giving cosmic waters that prophets such as Ezekiel (47:1-6, 12), Joel (3:18) and Zechariah (Zech. 14:8) spoke about (2000, 41). Inside the Temple the presence of Yahweh was enthroned on the cherubim situated on the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark also symbolized Yahweh’s dominion over creation. Cross has shown that the procession of the Ark at the Autumn New Year’s festival celebrated Yahweh’s victory over the primordial forces of chaos, in particular, and his return to Zion as the conquering hero (Cross 1973, 91-111). Thus the Temple and its surrounding environs could be viewed as the place where heaven and earth converged. From here “order was established at creation and was continually renewed and maintained through religious ritual and ceremony” (Stager 2000, 37). Moreover, the palace of the king was located next to Yahweh’s Temple. The physical proximity between Temple and palace was significant because it symbolized the unique relationship between Yahweh and the king. The king was called Yahweh’s son (Ps. 2) and he enjoyed divine sponsorship to preside over Yahweh’s people. He was selected by Yahweh to be the representative of divine authority. As Yahweh’s divine representative, the king extended the cosmic order which Yahweh established at creation to the Israelite people he governed. On Zion, therefore, the symbols of creation and political/social order (Temple and palace) were linked in a tangible way. In closing, this paper has tried to demonstrate that there is a relationship between the historical context in which the creation narratives were written and the events they attempted to 23 describe. As a result, on one level, creation narratives have as much to say about the mundane and the secular as they do about the metaphysical world of the cosmos. This is evident, for example, in their attempt to provide an explanation for the existence for certain phenomena related to the human or natural realm, whether it was searching for the source of pain in a toothache or in the event of childbirth. The connection between the cosmos and earth is also evident in the way the writers of these texts (both biblical and non-biblical) tied the emergence of political and social order to creation itself, especially in relation to the deity’s battle with chaos. In this way creation narratives represented or spoke of the social and political realities of a particular society, whether it was the events that led to kingship in Mesopotamia, the origins of the people of Israel, or the election of the Davidic king. Thus, in examining creation narratives we can learn just as much about the ancient societies that produced these accounts as we can about how the universe took shape. In essence, this type of understanding about creation narrative reduces the monumental gap between the cosmos (the world of the gods) and earth (the world of humans), so it can be said that what took plaice in the heavens also happened on earth. The ramifications of this are also pertinent to the theme of this particular conference. In thinking about the relationship between creation and science, I believe it is important that we keep this understanding about the nature and function of ancient creation narratives in the forefront of our minds, so that when biblical scholars, theologians and scientists come to the table and dialogue about these issues it will lead to more honest, intellectual, and productive discussions which will benefit society and the Church in the long run. 24 Bibliography Anderson, Bernhard W. “Mythopoeic and Theological Dimensions of Biblical Creation Faith.” Pages 1-24 in Creation in the Old Testament. Edited by Bernhard W. Anderson. Vol. 6 of Issues in Religion and Theology, ed. by Douglas Knight and Robert Morgan; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984. Brueggeman, Walter. “The Book of Exodus,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible. Vol. 1. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. Cassuto, Umberto. A Commentary on the Book of Exodus. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1983. Clifford, Richard J. “The Hebrew Scriptures and the Theology of Creation.” Theological Studies 46 (1985): 507-523. _______________ “Psalm 89: A Lament Over the Davidic Ruler’s Continued Failure.” Harvard Theological Review 73 (1980): 35-47. Cross, Frank. M. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973. Gunkel, Hermann. “The Influence of Babylonian Mythology Upon the Biblical Creation Story.” Pages 25-52 in Creation in the Old Testament. Edited by Bernhard W. Anderson. Vol. 6 of Issues in Religion and Theology, ed. by Douglas Knight and Robert Morgan; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984. Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. “The Atrahasis Epic and Its Significance for Our Understanding of Genesis 1-9.” Biblical Archaeologist 40 (1974): 147-55. Hasel, Gerhard. “The Polemic Nature of the Genesis Cosmology.” Evangelical Quarterly 2 (1974): 81-102. Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976. McCarthy, Dennis J. “Creation Motifs in Ancient Hebrew Poetry.” Pages 74-89 in Creation in the Old Testament. Edited by Bernhard W. Anderson. Vol. 6 of Issues in Religion and Theology, ed. by Douglas Knight and Robert Morgan; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984. O’Brien Wilfred Major, Joan. In the Beginning: Creation Myths from Ancient Mesopotamia, Israel and Greece. Chico: Scholars Press, 1982. Oden, Robert A. “Myth and Mythology,” ABD 4:946-56. 25 _____________ “Myth and Mythology (OT),” ABD 4:956-60. Propp, William C. Exodus 1-18. The Anchor Bible. New York: Doubleday, 1999. Khurt, Amelie. The Ancient Near East: c. 3000-330 BC. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge, 1995. Lambert, W.G. “The Reign of Nebuchadnezzar I: A Turning Point in the History of Ancient Mesopotamian Religion,” in The Seed of Wisdom. Edited by W.S. McCullough. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1964. Pritchard, James B., ed. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Related to the Old Testament. 3rd ed. Princenton: Princeton University Press, 1969. Schmid, H.H. “Creation Righteousness, and Salvation.” Pages 102-17 in Creation in the Old Testament. Edited by Bernhard W. Anderson. Vol. 6 of Issues in Religion and Theology, ed. by Douglas Knight and Robert Morgan; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984. Sproul, Barbara C. Primal Myths: Creating the World. New York: Harper and Row, 1979. Stager, Lawrence. “Jerusalem as Eden.” Biblical Archaeological Review 26 (2000): Trible, Phyllis. “Feminist Hermeneutics and Biblical Studies.” Pages 400-8 in Flowering of Old Testament Theology. Ed. by Ben C. Ollenberger, et al. Vol. 1 of Sources for Biblical and Theological Study. Ed. by Ben C. Ollenberger. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1992. Van De Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East: ca. 3000-323 BC. Malden: Blackwell, 2004. Van Tover, Raymond. ed. Sun Songs: Creation Myths From Around the World. New York: Mentor, 1980. Van Wolde, Ellen. Stories of the Beginning: Genesis 1-11 and Other Creation Stories. Ridgefield: Morehouse, 1996. Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2006. 26