narratives imagine

advertisement

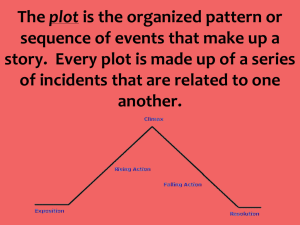

DRAFT December 8, 2005 Please do not quote for publication Analyzing Plot Chapter One The Guides for Analyzing a Plot The way of approaching plot described in this book begins with a few guidelines. Sometimes they are self-evident (readers experience plot), and sometimes they are arguable (what is a reader?). I am going to set aside some of those arguments for the present, because behind some of them lie assumptions which will be my subject later on. The nature of self-identity, for example, changes with the kinds of worlds we imagine, and analyzing narrative will lead us to consideration of those worlds and what it means to be a reader in them. My claim is that the approach I will describe is highly generalizable, and not just for all kinds of narrative literature, from sitcoms to War and Peace. Whatever has narrative organization—some historical accounts and biographies, psychoanalytic case histories, some dreams, religious projections of the future of humankind—will yield insights to the approach. The analysis which the guidelines makes possible is the beginning but not the end of the consideration of plot. In this chapter I explain the guidelines. In the following chapter I discuss the basic causal modes of plots. The balance of the book gives examples of the kinds of narratives and the kinds of plots to be found there. The book is meant to equip you to analyze any plot, fictional or not, from any time and culture. Ten Guiding Assertions for Analysis of Plot 1. A plot is an experience of a reader, not of a character. 2. Plots move from the first word to the last in reader’s time. 3. A plot is a reader’s experience of change. 4. Plots build a sense of meaning. 5. Plots take place in a narrative world. 6. With the completion of a plot, the narrative world is more orderly than it was at the beginning of the plot. 7. All full plots reach a state of unstable equilibrium toward the middle. 8. Full plots do not look like pyramids. Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 2 9. Full plots look like snakes, with low points of order on either side of the middle. 10. The reason plots look like the plot snake may be that they describe the process of a full life. To Explain the Assertions 1. A plot is an experience of a reader, not of a character. It might seem that many characters’ experiences are busy in a plot, with all of the characters having their own stories as implied if not explicit presences in the narrative. Because characters hook our interest we naturally move toward one of their points of view when we try to analyze the process of a plot. But there is only one mind which can see the story whole (if it can be seen whole at all), and that is the reader’s. Plot is a property of a whole work. Characters may have their own experiences of a plot (as we imagine them), and may act out plots we can disentangle from the work, but only a reader can have an experience of a whole work. 2. Plots move from the first word to the last in reader’s time. (Of course, that may be the first motion of a narrative dance, or the first frame of a film.) We may find out something in the middle of a work which happened before the work began. So far as we are concerned, though, the event has its impact when we discover it. For the plot it does not matter when an event occurs in the world of the work. What matters is when it enters our experience. A character may reveal something that the character has known for a long time. It takes its place in the plot when we discover it. Many plots, particularly in recent years, repeat events with variations or from different characters’ differing points of view, with their differing powers of memory. The plot, if there be one at all, is composed of our sense of the parade of those variations. The distinction between a reconstructible sequence of events and the surface sequence presented in a narrative was first worked out by the Russian formalists in the 1930s. Since then a great deal has been written about time in narratives. The analysis of plot, however, deals with the events as they are presented to us, not as we can rearrange them in some historical order. In many narratives from antiquity on, the plotted pleasure of a work can arise from our acts of reconstruction. For example, we find out only toward the middle of Oedipus Tyrannus that Oedipus has murdered a man who may have been his own father. No matter how many times we read Oedipus Tyrannus, we must experience anew the discovery of the circumstances of the murder of Oedipus’s father if we are to experience the play at all fully. In the reconstructible sequence of events, the murder has occurred before the beginning of the play, but in the plot, we discover the circumstances as the characters do. 3. A plot is a reader’s experience of change. Change is what plot is about— change from a relatively disorderly to a relatively orderly situation. To analyze plot is to become aware of the ways in which we are experiencing change. Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 3 4. Plots build a sense of meaning. The change must be meaningful to be a part of a plot. Meaningless change undoes plot. Plot, then, has to do with cause and effect, as E. M. Forster famously observed: “Let us define a plot. We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. ‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot. The time-sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: ‘The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.’ This is a plot with a mystery in it, a form capable of high development. It suspends the time-sequence, it moves as far away from the story as its limitations will allow. Consider the death of the queen. If it is in a story we say ‘and then?’ If it is in a plot we ask ‘why?’ That is the fundamental difference between these two aspects of the novel.” (Page 86) It may be true, as some have said, that when we hear that the king died and then the queen, we do not need to know why to begin to imagine that there may be a causal connection between the two. That is, we habitually tend to construe meanings, to make plots from stories. Still, Forster’s distinction is useful in understanding the difference between journalism and plotted narration. To understand a newspaper account is simply to understand its version of what happened. To understand a novel is to apprehend a set of meaningful changes (or to register and appreciate their meaninglessness). What is more, the fundamental kinds of plot arise from the basic ways we imagine meaning arising from the connections among events—that is, the kinds of relationships among causes and effects. Those ways are the plot modes, and there are exactly five of them. But that is for later in the book. 5. Plots take place in a narrative world. The narrative world is that implied and constructed by the narrative, and in which the story unfolds. It exists in our experience of the text and is made possible by it. Sometimes no immediately discernible difference exists between the narrative world and our own, but plot analysis can always yield statements about ways in which the narrative world limits itself in the kinds of experience it can encompass. In a way, the narrative world is there to allow certain kinds of experience and to prohibit others. That is the major way a narrative world differs from what we might call the world of absolute experience, the world beyond narrative. 6. With the completion of a plot, the narrative world is more orderly than it was at the beginning of the plot. The work of plot is generally to posit some disruption of a narrative world and then, through the process of the plot, to achieve a state of events which accommodates the disruption. Because the narrative world has successfully absorbed the disruption it is more powerfully ordered than it was before. Any suggestion of a sequence of similar disruptions to be managed in the future moves toward undoing the sense of closure in a plot. 7. All full plots reach a state of unstable equilibrium toward the middle. In his Poetics Aristotle observes that plots have beginnings, middles, and ends. He uses the metaphor of a knot: the first half of a plot ties a knot and the last half unties it. The unstable equilibrium of the tied knot in the middle of the plot, the climax, does in fact Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 4 characterize plots, and has been the most widely applied observation of the Aristotelian tradition for analyzing plot. Plots begin with a disruption and toward the middle reach what seems to be a solution to what seems to be the problem. Cinderella wants to go to a ball and Odysseus wants to return to Ithaca. Toward the middle of their narratives they get what they want. Oedipus wants to find out who killed Laius; at the climax of Oedipus Tyrannus he discovers who did (and it was him). But Aristotle’s metaphor of the plot knot wars with successful analysis. It implies that the plot develops in a straight line to the climax, and that the whole business of the last part of the narrative will be to undo the climax. Such is not the case. 8. Full plots do not look like pyramids. Early commentaries on Aristotle extended the comments of the Poetics to describe a model of plot form: an induction, which sets the scene; a development, leading to a climax, followed by a denouement and finally a catastrophe. The modern statement of the tradition began with Gustav Freytag, a German critic and theorist of drama who in the mid-nineteenth century described plot as a pyramid. Freytag’s pyramid is still widely taught as the standard model of plot; it is mentioned by most of those literary scholars who comment on plot form. It is taught, it is mentioned, and then it is dropped. It is of little use in analyzing actual plots because plots do not work that way. Important stages escape analysis when we try to imagine the plot of an actual work as a straight ascent to a climax and a straight descent to a catastrophe. 9. Full plots look like snakes, with low points of order on either side of the middle. Plots move in reader’s time to construct order. If we sketch a plot in these two dimensions, (reader’s) time and order, it will look like this: Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 5 Figure One: General Plot Form Order → 6 5 3 1 2 4 4 Reader’s time → 1. 2. 3. 4. Initiation Burnt Temporary Infernal Fingers Binding Vision 5. 6. Final Termination Binding Fig. 1. Plot Snake with General Process Stages. Adapted from Allen Tilley, Plot Snakes and the Dynamics of Narrative Experience (Gainesville: UP of FL, 1992), Fig. 1, p.3 Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 6 Stage one, the initiation, begins with the first word and proceeds until the turn to stage two, at the top of the first rise. In the intiation some actual or prospective change threatens (or has already began threatening) a stable narrative world. In the second stage, burnt fingers, the threat to order makes itself felt in a seemingly random and confused way. “Burnt fingers” carries the sense that characters are encountering surprises, often unpleasant ones, as they confront dangers they do not yet understand. In fact, at this early stage of the plot the dangers often seem to lack any organization at all. The confusion generally spreads until the plot turns toward stage three, the temporary binding. The turn will be the point at which the temporary binding becomes the direction of events. Usually, it is the point at which the temporary binding becomes possible. With the temporary binding the energies which are disturbing the world of the plot seem—at least, seem—to take some form which makes them manageable. Perhaps characters simply escape the turmoil, or perhaps they come up with some stratagem which they hope will deal with the difficulties which have beset them, or satisfy the desires which arouse them. They are doomed to disappointment, as the temporary bindings are always, in the end, unsatisfactory and ineffective. The turn from the temporary binding to the infernal vision is at the top of the middle rise. At that point, the instability of the temporary binding manifests itself and the central threat to order in the plot emerges. It does its worst until the lowest level of order in the work, the turn to stage five, the final binding. In that turn whatever solution the plot affords for the difficulties of the plot does its work. When it has finished, at the top of the last rise, the plot turns toward stage six, termination, which reestablishes a stable world which will continue beyond the end of the work. (Unless, of course, the final binding involved the end of the world—truly apocalyptic plots may lack a termination.) In terms of the order in Oedipus’s narrative world, things fall apart most when he discovers that in murdering Laius he has murdered his father and married his mother, all unwittingly. That is his infernal vision, the turn from stage four to stage five, and leads to his mother’s suicide and his own self-blinding and exile by Creon, which constitute the final binding, stage five. The murderer of Laius (Oedipus) has been discovered and banished, as the oracle demanded. Oedipus’s leavetaking constitutes the termination, stage six. The end of Oedipus Tyrannus is more orderly than the beginning, when a plague of unknown origin was preventing all generation in Thebes. The possibility of the succession of generations is restored. The plague is the initiation of the plot. It is the disruption of the formerly orderly narrative world which the plot must accommodate. The runners from the oracle of Apollo announce that to end the plague Laius’s murderer must be caught. This turn to the second stage, burnt fingers, leads to Oedipus’s interrogation of Tiresias, the blind seer who knows but will not name the murderer. With its dark hints from Tiresias and threats of violence by Oedipus, the interrogation tears at the civil peace of Thebes until it sets Oedipus against Creon, his brother-in-law and most valuable official. The orderly society of Thebes is coming undone. Notice that events at this stage of the play cannot usefully be imagined as a straight line to the climax. The turn to the temporary binding, the third stage, comes with the arrival of Jocasta, who is able to calm Oedipus. The third stage is relatively brief. It leads to her revelation that Laius was killed by a stranger where three roads meet. She means to calm Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 7 Oedipus but instead has unwittingly informed him that he is the murderer for whom he has been searching. Oedipus’s drive to discover the full truth of the situation leads him along the descent of the fourth stage, the infernal vision, to the terrible news from the shepherd and the messenger: Oedipus is not who he thought he was, and has acted out a terrible prophecy which he fled Corinth to escape. In the final binding stage the revelation has its effect—suicide and mutilation. With the blinded Oedipus’s reentry before Creon the plot moves to termination, the reestablishment of an orderly world which will continue beyond the end of the play. Oedipus is banished from Thebes, now purged, and Creon will rule. We know that Oedipus’s sons will not be able to share power, that a devastating war will ensue. We also know that Oedipus’s daughters and Oedipus himself are due for a dramatic future. Antigone has her own tragedy to play out, and Oedipus is more blessed than he can now know. To the extent that the energies of the play are unsatisfied the plot is unbound. But in this play, the primary disruption, the plague and, behind it, the unwitting patricide and incest, have been revealed and accommodated, so that the plot achieves sufficient closure to satisfy readers. The general plot process I have described for Oedipus Tyrannus will serve to account for every full plot which comes to closure (though not all do, as I shall describe later). Partial plots, such as brief anecdotes and jokes, look more like Freytag’s pyramid, or like a straight march to a punch line. But full plots which come to closure, from whatever context of culture, time, race, and gender, look like the plot snake. Or so I claim, as unlikely as that may seem. I hope you will entertain for the present discussion the possibility that it may be so. 10. The reason plots look like the plot snake may be that they describe the process of a full life. The regularity and persistence of plot, the way in which the six stages organize narratives from ancient plays to tonight’s situation comedy, asks for an explanation. Life initiates with a birth. The turn to the second stage comes when we achieve some independence from our parents and are able to move around the world on our own, about our sixth year. We are at that point headed for adolescence. The stages have biological markers; the end of the second stage and the turn to the third is marked by puberty, when our personality comes more or less unglued and reforms itself around the goal of the temporary binding of life, achievement of adult status. The biological marker is birth of children, but whatever marks adult status will do as the high point of order in the middle of life’s plot snake. In spite of what teenagers think, adult status is not the end of life. The infernal vision of our life is the point at which we realize that friends, job, and family will not save us from the death which lies ahead. The biological marker of the infernal vision is menopause, at least for about half of us. (The male climacteric is still in dispute.) In the turn from the infernal vision to the final binding, we move out of the chaos of midlife to an acceptance of our life’s shape, or at least to a viewpoint from which we can recognize the shape of what we have done and become. Death is of course the biological marker of our final binding phase of life. It might seem that if the life-cycle were behind plot, more plots would end with a sense of Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 8 devastating waste or emptiness, for death often seems that way to us—an empty waste. But that is not necessarily the way death comes. Studies of the death experience show that few deaths come in panicked pain. From the vantage point of a full life, if ever, we can see life whole. Of course, if we are to attain that vantage, it will likely be somewhat before death. Most people at their very end are too busy dying to take philosophical notice of anything about their life. At least in our stories, though, we imagine a viewpoint from which we can see life whole, even if the view is tragic. Often it is not. The midlife transition is the point at which we seem most strangers in the world, out of place in our lives. The things we have built our lives around no longer sustain us. In old age we again take our places in the continuity of experience, and have a chance to become at home again in the world. The sixth stage, termination, names whatever continues beyond a death—society moving on beyond us, an afterlife, persistence in the memories or the lineage of those left behind. The termination imagines a world augmented by the life now passed. Plot form is ancient, and may as easily be discerned in Gilgamesh (our plot of most ancient record, about four thousand years ago) as in modern narratives. Some people overly impressed with the claims of modernity imagine people lived only short lives until recently. In whatever ancient source you choose, however, a full life is represented as having the full complement of stages and cannot be said to be complete until at least the seventh decade. It is so in the Bible and in Plato and in Confucius. Infant mortality, childhood diseases, warfare, and the dangers of childbirth have held the average lifespan down in the past but those who succeed in weaving past the dangers lived full lives as today, and were examples to their communities. Not very many plots end with literal death. More probably end with a marriage or some other marker of an achievement in the stream of life. If my guess is right, though, behind the form of all full plots which come to closure lies the pattern of a full life. I cannot tell the story of my life until it is too late for me to tell it. But through narrative I can imagine the shape of the whole. So we seem to do, in infinite variation, practicing again and again the full shape of our experience. Supplementary Notes Chapter one, Plot Form. The system presented here is one I have developed in two books: Plot Snakes and the Dynamics of Narrative Experience (Gainesville: UP of Florida, 1992), and Plots of Time: An Inquiry into History, Myth, and Meaning (Gainesville: UP of Florida, 1995). I do not assume acquaintance with either of these here. In fact, I believe the books will be easier to read if you start with this one, for in the previous books I have been at pains to develop and defend the theory and to show its relationship to past treatments of plot. In this book I omit that and must refer you to the previous two for such matters as the history of Freytag’s Pyramid and the controversy over the male climacteric. A recent and most useful introduction to narrative theory in general is H. Porter Abbott’s The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002). My books are not represented but it is a good survey nonetheless. Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 9 The edition of E. M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel I have quoted was printed in New York in 1955 by Harcourt, Brace, & World Inc. The passage comes a couple of pages into his Chapter Five, “The Plot.” The book was written in 1927, and is still much worth reading for its good sense and insights. The whole idea of plot as a dynamic system I derived from an NEH summer seminar with Peter Brooks, who was at the time working on Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative (New York: Knopf, 1984). The idea is especially developed in his chapter “Freud’s Masterplot.” Some thoughts about entropy and plot: In thermodynamics, a closed system—in our case, a narrative world—always becomes less orderly with time. The more entropy a system has, the less information we have about it and the less orderly it is. A hot cup of coffee in a closed room cools. The heat is still there but more randomly dispersed as the coffee cools. Entropy describes the dispersion of that heat. Plots work in the opposite way. With the passage of reader’s time, from frame to frame of a film or word to word of a novel, the narrative world is on its way to increased order (or this is a narrative which is out to defeat plot, as some are). By Boltzman’s formula the entropy of a physical system may be exactly measured and expressed. I know of no way to do that for a narrative. In two ways, then, a narrative is a bad fit for the laws of thermodynamics: entropy lessens over time to the extent that a plot comes to closure, and the growth in order may be sensed and described but not measured. (At least, not so far as I know.) The world is a bad fit for the laws of entropy for exactly the same reasons. Over the past four and a half billion years the earth has become more highly organized. It has gone from a relatively simple world of the basic elements to the present swarm of highly organized living beings. A rat is more highly organized than a palm tree; in time, the rats, and we with them, have joined the palm trees in the world. What is more, we have no way to measure exactly that increase in complexity. This view (of the increasing complexity of the ecosystem) is usually regarded as superficial because the world has received an excess of energy from the sun for all those four and a half billion years. That excess energy has driven entropy backwards, into negentropy and an increase in complexity. Physicists assure us that if we stick around long enough for the sun to go out we shall observe that on a sufficiently long time scale the laws of entropy will assert themselves and the world will proceed to become simple indeed. The world itself is due to dissolve in time. The entropy of a narrative plot which comes to closure works on human time scales, those we can observe on the scale of a lifetime. On those scales the energies of plot may be accommodated or, as Peter Brooks has said, bound by events. Many may say, so much for plot, and so much for our narratives. They only serve to create the illusion of a future. But the deep need for meaning which drives plot may be more than a need to deny death; it may be a hint of the timelessness of the achievements of time. William Blake thought so: “Eternity is in love with the productions of time.” Plots sometimes do, and sometimes do not, look beyond death. Beginnings and endings are great mysteries. In our experience, nothing begins from absolutely nowhere or ends with no sequel whatsoever. So with plot, really. About the only way for a plot to truly begin at the beginning is to start as medieval chronicles Analyzing Plot: Ch 1 10 customarily did, with the beginning of the world. And the only end which is final imagines the cessation of time. Neither is wholly accessible to our imaginations. In the past I have used entropy as a metaphor for plot process, and called the vertical dimension of my plot snake by that name. I have come to believe that finally I must drop the entropy metaphor. For plot, the achievement of order accounts for something, even if we are left the annihilated worlds of Oedipus Tyrannus or King Lear. Thermodynamics has no way to recognize lessons learned, secrets revealed, or realities faced. Our sense of plot does.