Chronic Care Programme

advertisement

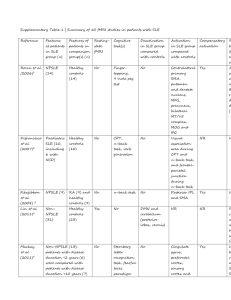

Chronic Care Programme Treatment guidelines Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Chronic condition Consultations protocols Preferred treating provider Notes preferred as indicated by option referral protocols apply Option/plan Provider GMHPP Gold Options G1000, G500 and G200. Blue Options B300 and B200. GMISHPP General Practitioner Paediatrician Cardiologist Neurologist Physician Pulmonologist Dermatologist Mild Maximum consultations per annum Initial consultation Follow-up consultation Tariff codes New Patient Existing Patient 1 1 1 1 0183; 0142; 0187; 0108 Severe New & Existing patient 1 1 Investigations protocols Type Provider Tariff code Urine dipstick (per stick, irrespective of the number of tests on stick) Blood glucose: quantitative Blood glucose: strip test with photometric reading ECG without effort Flow volume test: inspiration/expiration ESR CRP ANF (Auto-antibodies by labelled anti-bodies) Anti-DNA Anti-phospholipids antibodies Haemoglobin estimation Leucocytes: total count Platelets AST ALT GGT Alkaline phosphatase Serum albumin Serum potassium GP; Specialist; Pathologist Maximum investigations per annum New patient Existing patient New & Existing patient 4188 6 4 6 GP; Specialist; Pathologist GP; Specialist; Pathologist GP or Specialist (see list) GP or specialist (see list) GP; Specialist; Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist 4057 1 1 1 4050 1 1 1 1232 1 0 1 1168 1 0 1 3743 4 2 4 3947 3934 1 1 1 1 1 2 Pathologist Pathologist 4182 3934 1 1 1 1 2 2 GP; Specialist; Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist 3762 4 4 6 3785 3797 4130 4131 4134 4001 3999 4113 4 4 0 0 0 0 0 1 4 4 0 0 0 0 0 1 6 6 6 6 1 6 1 4 Serum sodium Serum urea Serum creatinine Creatinine clearance Urine protein (quantitative) Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist Pathologist ICD 10 coding 4114 4151 4032 4223 4213 1 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 4 4 4 2 2 M32. L93. General Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus) is a chronic autoimmune disease that can be fatal, though with recent medical advances, fatalities are becoming increasingly rare. As with other autoimmune diseases, the immune system attacks the body’s cells and tissue, resulting in inflammation and tissue damage. SLE can affect any part of the body, but most often harms the heart, joints, skin, lungs, blood vessels, liver, kidneys and nervous system. The course of the disease is unpredictable, with periods of illness (called flares) alternating with remission. Lupus can occur at any age, and is most common in women, particularly of non-European descent.[1] Lupus is treatable symptomatically, mainly with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, though there is currently no cure. Survival in patients with SLE in the United States, Canada and Europe is approximately 95% at 5 years, 90% at 10 years, and 78% at 20 years.[2] Classification Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease. Clinically, it can affect multiple organ systems including the heart, skin, joints, kidneys and nervous system. There are several types of lupus; generally when the word 'lupus' alone is used, it refers to the systemic lupus erythematosus or SLE as discussed in this article. Other types include: Drug-induced lupus erythematosus, a drug-induced form of SLE; this type of lupus can occur equally for either gender Lupus nephritis, an inflammation of the kidneys caused by SLE Discoid lupus erythematosus, a skin disorder which causes a red, raised rash on the face,and scalp. Discoid Lupus occasionally (1-5%) develops into SLE[3] Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, which causes non-scarring skin lesions on patches of skin exposed to sunlight[4] Neonatal lupus, a rare disease affecting babies born to women with SLE, Sjögren's syndrome or sometimes no autoimmune disorder. It is theorized that maternal antibodies attack the fetus, causing skin rash, liver problems, low blood counts (which gradually fade) and heart block leading to bradycardia.[4] Signs and symptoms SLE is one of several diseases known as "the great imitators" [5] because its symptoms vary so widely it often mimics or is mistaken for other illnesses, and because the symptoms come and go unpredictably. Diagnosis can be elusive, with patients sometimes suffering unexplained symptoms and untreated SLE for years. Common initial and chronic complaints are fever, malaise, joint pains, myalgias and fatigue. Because they are so often seen with other diseases, these signs and symptoms are not part of the diagnostic criteria for SLE. When occurring in conjunction with other signs and symptoms (below), however, they are considered suggestive. Common symptoms explained Dermatological manifestations As many as 30% of patients present with some dermatological symptoms (and 65% suffer such symptoms at some point), with 30% to 50% suffering from the classic malar rash (or butterfly rash) associated with the disease. Patients may present with discoid lupus (thick, red scaly patches on the skin). Alopecia, mouth, nasal, and vaginal ulcers, and lesions on the skin are also possible manifestations. Musculoskeletal manifestations Patients most often seek medical attention for joint pain, with small joints of the hand and wrist usually affected, although any joint is at risk. The Lupus Foundation of America "estimates more than 90 percent will experience joint and/or muscle pain at some time during the course of their illness".[6] Unlike rheumatoid arthritis, lupus arthritis is less disabling and it usually does not cause severe destruction of the joints. Fewer than 10 percent of people with lupus arthritis will develop deformities of the hands and feet.[6] Hematological manifestations Anemia and iron deficiency may develop in as many as half of patients. Low platelet and white blood cell counts may be due to the disease or a side-effect of pharmacological treatment. Patients may have an association with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (a thrombotic disorder) where autoantibodies to phospholipids are present in the patient's serum. Abnormalities associated with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome include a paradoxical prolonged PTT (which usually occurs in hemorrhagic disorders) and a positive test for antiphospholipid antibodies; the combination of such findings have earned the term "lupus anticoagulant positive". Another autoantibody finding in lupus is the anticardiolipin antibody which can cause a false positive test for syphilis. Cardiac manifestations Patients may present with inflammation of various parts of the heart, such as pericarditis, myocarditis, and endocarditis. The endocarditis of SLE is characteristically non-infective (Libman-Sacks endocarditis) and involves either the mitral valve or the tricuspid valve. Atherosclerosis also tends to occur more often and advance more rapidly in SLE patients than in the general population.[7][8][9] Pulmonary manifestations Lung and pleura inflammation can cause pleuritis, pleural effusion, lupus pneumonitis, chronic diffuse interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary emboli, pulmonary hemorrhage. Hepatic involvement See autoimmune hepatitis Renal involvement Painless hematuria or proteinuria may often be the only presenting renal symptom. Acute or chronic renal impairment may develop with lupus nephritis, leading to acute or end stage renal failure. Because of early recognition and management of SLE, end stage renal failure occurs in less than 5% of patients. Histologically, a hallmark of SLE is membranous glomerulonephritis with "wire loop" abnormalities.[10] This finding is due to immune complex deposition along the glomerular basement membrane leading to a typical granular appearance in immunofluorescence testing. Neurological manifestations About 10% of patients may present with seizures or psychosis. A third may test positive for abnormalities in the cerebrospinal fluid. T-cell abnormalities Abnormalities in T cell signaling are associated with SLE, including deficiency in CD45 phosphatase and increased expression of CD40 ligand. Other rarer manifestations lupus gastroenteritis, lupus pancreatitis, lupus cystitis, autoimmune inner ear disease, parasympathetic dysfunction, retinal vasculitis, and systemic vasculitis. Other abnormalities include: Increased expression of FcεRIγ, which replaces the sometimes deficient TCR ζ chain Increased and sustained calcium levels in T cells Moderate increase of inositol triphosphate Reduction in PKC phosphorylation Reduction in Ras-MAP kinase signaling Deficiencies in protein kinase A I activity Diagnosis Microphotograph of a histological section of human skin prepared for direct immunofluorescence using an anti-IgG antibody. The skin is from a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and shows IgG deposit at two different places : the first is a band-like deposit along the epidermal basement membrane ("lupus band test" is positive), the second is within the nuclei of the epidermal cells (anti-nuclear antibodies are present). Some physicians make a diagnosis on the basis of the ACR classification criteria (see below). The criteria, however, were established mainly for use in scientific research (i.e. inclusion in randomized controlled trials), and patients may have lupus but never meet the full criteria. Anti-nuclear antibody testing and anti-extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) form the mainstay of serologic testing for lupus. Antiphospholipid antibodies occur more often in SLE, and can predispose for thrombosis. More specific are the anti-smith and anti-dsDNA antibodies. Other tests routinely performed in suspected SLE are complement system levels (low levels suggest consumption by the immune system), electrolytes and renal function (disturbed if the kidney is involved), liver enzymes and a complete blood count. Formerly, the lupus erythematosus (LE) cell test was not commonly used for diagnosis because those LE cells are only found in 50-75% of SLE patients, and are also found in some patients with rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, and drug sensitivities. Because of this, the LE cell test is now performed only rarely and is mostly of historical significance.[16] Diagnostic criteria The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has established eleven criteria in 1982,[17] which were revised in 1997[18] as a classificatory instrument to operationalise the definition of SLE in clinical trials. They were not intended to be used to diagnose individual patients and do not do well in that capacity. For inclusion in clinical trials, patients must meet the following three criteria to be classified as having SLE: (i) patient must present with four of the below eleven symptoms (ii) either simultaneously or serially (iii) during a given period of observation. 1. Serositis: Pleuritis (inflammation of the membrane around the lungs) or pericarditis (inflammation of the membrane around the heart)sensitivity = 56%; specificity = 86% (pleural is more sensitive; cardiac is more specific)[19] 2. Oral ulcers: include oral or nasopharyngeal ulcers 3. [[Arthritis]]: nonerosive arthritis of two or more peripheral joints, with tenderness, swelling or effusionsensitivity = 86%; specificity = 37%[19] 4. [[Photodermatitis|Photosensitivity]] (exposure to ultraviolet light causes rash). sensitivity = 43%; specificity = 96%[19] 5. Blood: Hematologic disorder: Hemolytic anemia (low red blood cell count) or leukopenia (white blood cell count<4000/ul), lymphopenia ( <1500/ul ) or thrombocytopenia (<100000/uL) in the absence of offending drug.sensitivity = 59%; specificity = 89%[19] Hypocomplementemia is also seen, due to either consumption of C3 and C4 by immune complex-induced inflammation, or to congenitally complement deficiency, which may predispose to SLE. 6. Renal disorder: More than 0.5 g per day protein in urine, or cellular casts seen in urine under a microscope.sensitivity = 51%; specificity = 94%[19] 7. [[Anti-nuclear antibody]] test positive. sensitivity = 99%; specificity = 49%[19] 8. Immunologic disorder: Positive anti-Sm, anti-ds DNA, anti-phospholipid antibody and/or false positive serological test for syphilis. sensitivity = 85%; specificity = 93%[19]. Presence of anti-ss DNA in 70% of patients (though also positive in patients with rheumatic disease and healthy persons[20]) 9. Neurologic disorder: Seizures or psychosis. sensitivity = 20%; specificity = 98%[19] 10. [[Malar rash]] (rash on cheeks). sensitivity = 57%; specificity = 96%[19] 11. Discoid lupus (red, scaly patches on skin which cause scarring) sensitivity = 18%; specificity = 99%[19] A useful mnemonic for these 11 criteria is SOAP BRAIN MD: Serositis (8), Oral ulcers (4), Arthritis (5), Photosensitivity (3), Blood Changes (9), Renal involvement (proteinuria or casts) (6), ANA (10), Immunological changes (11), Neurological signs (seizures, frank psychosis) (7), Malar Rash (1), Discoid Rash (2). Some patients, especially those with antiphospholipid syndrome, may have SLE without four criteria and SLE is associated with manifestations other than those listed in the criteria.[21][22][23] [edit] Alternative criteria Recursive partitioning has been used to identify more parsimonious criteria.[19] This analysis presented two diagnostic classification trees: 1. Simplest classification tree: LSE is diagnosed if the patient has an immunologic disorder (antiDNA antibody, anti-Smith antibody, false positive syphilis test, or LE cells) or malar rash. sensitivity = 92% specificity = 92% 2. Full classification tree: Uses 6 criteria. sensitivity = 97% specificity = 95% Other alternative criteria have been suggested.[24] Common misdiagnoses Porphyria Porphyrias are complex genetic disorders that share many symptoms with lupus, but impact the enzymes responsible for building heme, a component needed in heme proteins. Porphyrias are ecogenic disorders requiring both environmental and genetic backgrounds to manifest with a variety of symptoms and medical complications. They are noted for photosensitivity and have been associated with transient and permanent production of autoantibodies. The five major forms of dominantly inherited porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria, porphyria cutanea tarda, hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria and erythropoietic protoporphyria) have been detected in systemic lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus patients over the past 50 years. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion of porphyrias in all lupus cases and act accordingly when patients are in a medical crisis that may be due to an underlying acute hepatic porphyria. Drug-induced lupus and photosensitivity warrant an investigation for an underlying porphyria since multiple drug reactions are a hallmark complication of porphyrias. Patients with both lupus and porphyrias should avoid porphyrinogenic drugs and hormone preparations. Patients with acute hepatic porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria) have been detected in lupus patients with severe life-threatening "lupus" complications known as neurolupus. Symptoms are identical to acute hepatic porphyria attacks and include seizures, psychosis, peripheral neuropathy and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) associated with dangerously low sodium levels (hyponatremia). Porphyria attacks require intervention with intravenous glucose, heme preparations and the discontinuation of dangerous porphyrinogenic drugs including antiseizure drugs. Several other lupus complications have been associated with porphyrias including pancreatitis and pericarditis. Porphyrin testing should be performed on urine, stool/bile and blood to detect all types of porphyrias, and repeat testing should be performed in suspicious cases. Appropriate enzyme tests or DNA testing should also be pursued to obtain a complete diagnosis which could include a dual porphyria. Common dual diagnoses SLE is sometimes diagnosed in conjunction with other conditions, including Rheumatoid Arthritis, Scurvy and Fibromyalgia. Treatment As lupus erythematosus is a chronic disease with no known cure, treatment is restricted to dealing with the symptoms; essentially this involves preventing flares and reducing their severity and duration when they occur. There are several means of preventing and dealing with flares, including drugs, alternative medicine and lifestyle changes. Drug therapy Due to the variety of symptoms and organ system involvement with Lupus patients, the severity of the SLE in a particular patient must be assessed in order to successfully treat SLE. Mild or remittent disease can sometimes be safely left untreated. If required, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug and anti-malarials may be used. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are used preventively to reduce incidence of flares, the process of the disease, and lower the need for steroid use; when flares occur, they are treated with corticosteroids. DMARDs commonly in use are anti-malarials and immunosuppressants (e.g. methotrexate and azathioprine). Hydroxychloroquine (trade name Plaquenil) is an FDA approved anti-malarial used for constitutional, cutaneous, and articular manifestations, while Cyclophosphamide (trade names Cytoxan and Neosar) is used for severe glomerulonephritis or other organ-damaging complications, and in 2005, mycophenolic acid (trade name CellCept) became accepted for treatment of lupus nephritis. In more severe cases, medications that modulate the immune system (primarily corticosteroids and Immunosuppresive drug immunosuppressants) are used to control the disease and prevent recurrence of symptoms (known as flares). Patients who require steroids frequently may develop obesity, diabetes mellitus, diabetes and osteoporosis. Depending on the dosage, corticosteroids can cause other side effects such as a puffy face, an unusually large appetite and difficulty sleeping. Those side effects can subside if and when the large initial dosage is reduced, but long term use of even low doses can cause elevated blood pressure and cataracts. Due to these side effects, steroids are avoided if possible. Since a large percentage of Lupus patients suffer from varying amounts of chronic pain, stronger prescription analgesics may be used if over-the-counter drugs, mainly non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug do not provide effective relief. Moderate pain in Lupus patients if typically treated with mild prescription opiates such as Dextropropoxyphene (trade name Darvocet), and Co-codamol (trade name Tylenol #3). Moderate to severe chronic pain is treated with stronger opioids such as Hydrocodone (trade names Lorcet, Lortab, Norco, Vicodin, Vicoprofen) or longer-acting continuous release opioids such as Oxycodone (trade names OxyContin), MS Contin, or Methadone. The Fentanyl Duragesic Transdermal patch is also a widely-used treatment option for chronic pain due to Lupus complications because of its long-acting timed release and easy usage. When opioids are used for prolonged periods drug tolerance, chemical dependency and (rarely) addiction may occur. Opiate addiction is not typically a concern for Lupus patients, since the condition is not likely to ever completely disappear. Thus, lifelong treatment with opioids is fairly common in Lupus patients that exhibit chronic pain symptoms; accompanied by periodic titration that is typical of any long-term opioid regimen. UVA1 phototherapy In 1987, Tina Lomardi, MD first reported that long-wave ultraviolet radiation (UVA1) had a favorable effect on disease activity in SLE model mice.[citation needed] In 1987, McGrath, Bak and Michalski reported in Arthritis and Rheumatism, Vol.30, No. 5, May, that long-wave ultraviolet radiation (UVA1) had a favorable effect on disease activity in SLE model mice ( "Ultraviolet-A Light Prolongs Survival and Improves Immune Function in Hybrid Mice") Both McGrath and independent Dutch searchers have repeatedly reproduced these findings in SLE patients. [25] Devices for administering therapeutic doses of UVA1 are available in Europe but not in the U.S. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration Office of Science and Technology conducted UVA1 phototherapy studies in an SLE mouse model in 1997 "to prepare for future reviews of UVAemitting tanning devices for such clinical applications".[26] Some patients, however, have taken matters into their own hands. Chicago-based reporter and lupus patient Anthony DeBartolo built his own 8-lamp UVA1 home tanning device which delivers the same 6 to 8 joule therapeutic dose of McGrath's 24-lamp clinical research equipment. DeBartolo's experiences were published in the 2004 book, "Lupus Underground." [27]. Lifestyle changes Other measures such as avoiding sunlight or covering up with sun protective clothing can also be effective in preventing problems due to photosensitivity. Weight loss is also recommended in overweight and obese patients to alleviate some of the effects of the disease, especially where joint involvement is significant. Treatment research Other immunosuppressants (drugs that lower the body's normal immune response) and bone marrow transplant autologous stem cell transplants are under investigation as a possible cure. Recently, treatments that are more specific in modifying the particular subset of the immune cells (e.g. B- or T- cells) or cytokine proteins they secrete have been gaining attention. Research into new treatments has recently been accelerated by genetic discoveries, especially mapping of the human genome. According to a June 2006 market analysis report by Datamonitor, treatment for SLE could be on the verge of a breakthrough as there are numerous late-Phase trials currently being carried out.[28] There have been promising advances in the area of stem cell research implicating a treatment with adult stem cells being harvested from the patients themselves.[29] [30] Medicine formularies Plan or option GMHPP Gold Options Link to appropriate Mediscor formulary G1000, G500 and G200 Blue Options B300 and B200 GMISHPP Blue Option B100 [Core] n/a Epidemiology Previously believed to be a rare disease, Lupus has seen an increase in awareness and education since the 1960s. This has helped many more patients get an accurate diagnosis making it possible to estimate the number of people with lupus. In the United States alone, it is estimated that between 270,000 and 1.5 million people have lupus, making it more common than cystic fibrosis or cerebral palsy. The disease affects both females and males, though young women are diagnosed nine times more often than men. SLE occurs with much greater severity among African-American women, who suffer more severe symptoms as well as a higher mortality rate.[32] Worldwide, a conservative estimate states that over 5 million people have lupus. Although SLE can occur in anyone at any age, it is most common in women of childbearing age. It affects 1 in 4000 people in the United States, with women becoming afflicted far more often than men. The disease appears to be more prevalent in women of African, Asian, Hispanic and Native American origin but this may be due to socioeconomic factors. People with relatives who suffer from SLE, rheumatoid arthritis or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura are at a slightly higher risk than the general population. Prognosis Prognosis In the 1950s, most patients diagnosed with SLE lived fewer than five years. Advances in diagnosis and treatment have improved survival to the point where over 90% of patients now survive for more than ten years and many can live relatively asymptomatically. The most common cause of death is infection due to immunosuppression as a result of medications used to manage the disease. Prognosis is normally worse for men and children than for women. Fortunately, if symptoms are present after age 60, the disease tends to run a more benign course. The ANA is the most sensitive screening test while Anti-Sm (Anti Smith) is the most specific. The ds-DNA (double-stranded DNA) antibody is also fairly specific and often fluctuates with disease activity. The ds-DNA titer is therefore sometimes useful to diagnose or monitor acute flares or response to treatment.[31] Epidemiology Prevention Lupus is not understood well enough to be prevented, but when the disease develops, quality of life can be improved through flare prevention. The warning signs of an impending flare include increased fatigue, pain, rash, fever, abdominal discomfort, headache and dizziness. Early recognition of warning signs and good communication with a doctor can help individuals with lupus remain active, experience less pain and reduce medical visits.[4]Prevention of complications during pregnancy Prevention of complications during pregnancy While most infants born to mothers with lupus are healthy, pregnant mothers with SLE should remain under a doctor's care until delivery. Neonatal lupus is rare, but identification of mothers at highest risk for complications allows for prompt treatment before or after birth. In addition, SLE can flare during pregnancy and proper treatment can maintain the health of the mother for longer. Women pregnant and known to have the antibodies for anti-Ro (SSA) or anti-La (SSB) should have echocardiograms during the 16th and 30th weeks of pregnancy to monitor the health of the heart and surrounding vasculature.[4] References 1. LUPUS FOUNDATION OF AMERICA. Retrieved on 2007-07-04. 2. [http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2859070 Harrison's Internal Medicine, 17th ed. Chapter 313. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. 3. Discoid Lupus Erythematosus 4. abcd Handout on Health: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. National Institutes of Health (August 2003). Retrieved on 2007-11-23. 5. Lupus: The Great Imitator 6. ab Joint and Muscle Pain Lupus Foundation of America 7. Yu Asanuma, M.D., Ph.D., Annette Oeser, B.S., Ayumi K. Shintani, Ph.D., M.P.H., Elizabeth Turner, M.D., Nancy Olsen, M.D., Sergio Fazio, M.D., Ph.D., MacRae F. Linton, M.D., Paolo Raggi, M.D., and C. Michael Stein, M.D. (2003). "Premature coronary-artery atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus". New England Journal of Medicine 349 (Dec. 18): 2407-2414. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035611. PMID 14681506 Abstract (full text requires registration). 8. Bevra Hannahs Hahn, M.D. (2003). "Systemic lupus erythematosus and accelerated atherosclerosis". New England Journal of Medicine 349 (Dec. 18): 2379-2380. PMID 14681501 Extract (full text requires registration). 9. Mary J. Roman, M.D., Beth-Ann Shanker, A.B., Adrienne Davis, A.B., Michael D. Lockshin, M.D., Lisa Sammaritano, M.D., Ronit Simantov, M.D., Mary K. Crow, M.D., Joseph E. Schwartz, Ph.D., Stephen A. Paget, M.D., Richard B. Devereux, M.D., and Jane E. Salmon, M.D. (2003). "Prevalence and correlates of accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus". New England Journal of Medicine 349 (Dec. 18): 23992406. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035471. PMID 14681505 Abstract (full text requires registration). 10. General Pathology Images for Immunopathology. Retrieved on 2007-07-24. 11. Anisur Rahman and David A. Isenberg (2008). "Review Article: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus". N Engl J Med 358 (9): 929-939. PMID 18305268. 12. Mary K. Crow (2008). "Collaboration, Genetic Associations, and Lupus Erythematosus". N Engl J Med 358 (9): 956-961. PMID 18204099. 13. Geoffrey Hom, Robert R. Graham, Barmak Modrek, et al. (2008). "Association of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with C8orf13–BLK and ITGAM–ITGAX". N Engl J Med 358 (9): 900-909. PMID 18204098. 14. University of South Carolina School of Medicine ledcture notes, Immunology, Hypersensitivity reactions. General discussion of hypersensitivity, not specific to SLE. 15. Gaipl, U S; Kuhn, A; Sheriff, A; Munoz, L E; Franz, S; Voll, R E; Kalden, J R; Herrmann, M (2006). "Clearance of apoptotic cells in human SLE.". Current directions in autoimmunity 9: 173-87. PMID: 1639466 Abstract (full text requires registration). 16. NIM encyclopedic article on the LE cell test 17. Rheumatology.org article on the classification of rheumatic diseases 18. Revision of Rheumatology.org's diagnostic criteria 19. a b c d e f g h i j k Edworthy SM, Zatarain E, McShane DJ, Bloch DA (1988). "Analysis of the 1982 ARA lupus criteria data set by recursive partitioning methodology: new insights into the relative merit of individual criteria". J. Rheumatol. 15 (10): 1493-8. PMID 3060613. 20. UpToDate Patient information article on DNA antibodies 21. Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG, et al (2003). "Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines". Lupus 12 (7): 530-4. doi:10.1191/0961203303lu394oa. PMID 12892393. 22. Sangle S, D'Cruz DP, Hughes GR (2005). "Livedo reticularis and pregnancy morbidity in patients negative for antiphospholipid antibodies". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64 (1): 147-8. doi:10.1136/ard.2004.020743. PMID 15608315. 23. Hughes GR, Khamashta MA (2003). "Seronegative antiphospholipid syndrome". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62 (12): 1127. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.006163. PMID 14644846. 24. Hughes GR (1998). "Is it lupus? The St. Thomas' Hospital "alternative" criteria". Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 16 (3): 250-2. PMID 9631744. 25. Light therapy (with UVA-1) for SLE patients: is it a good or bad idea? -- Pavel 45 (6): 653 -- Rheumatology. Retrieved on 2007-07-04. 26. Ultraviolet-A1 (UVA1) Phototherapy of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 27. "Lupus Underground" by Anthony DeBartolo; Hyde Park Media, 2004[1] 28. Lead Discovery article on treatment of Lupus 29. Medical News Today article 30. Northwestern Memorial Hospital Press Release 31. [EARLY STEROIDS MAY PREVENT RELAPSES IN LUPUS, P Jarman (Published in Journal Watch (General) July 18, 1995) 32. Lupus and African-American women