Annex to Chapter 1

advertisement

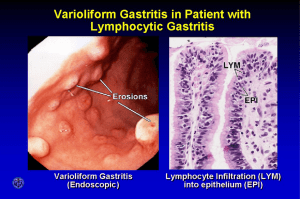

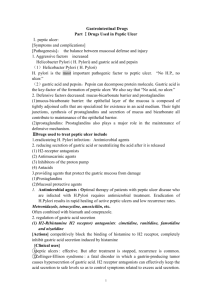

Annex to Chapter 1 Priority Medicines for Europe and the World "A Public Health Approach to Innovation" Background Paper for Review Annex to Chapter 1 Peptic Ulcer Disease “Pharmaceuticals Closing a Surgical Gap” By Saloni Tanna, Pharm.D; MPH 20 September 2004 Please send comments to: Dr Richard Laing E-mail: laingr@who.int Annex to Chapter 1-1 Annex to Chapter 1 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 3 From Surgery to Effective Pharmacological Therapies ......................................................................... 4 Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) .............................................................................................................. 6 Epidemiology .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Western countries............................................................................................................................. 7 Developing Countries...................................................................................................................... 7 Transmission ............................................................................................................................................... 7 Diagnostic Tests .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Therapy ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Time Trends in Peptic Ulcer Surgery – Pharmaceuticals Closing the Surgical Gap ......................... 9 Past and Current Research ............................................................................................................ 11 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................. 12 References .................................................................................................................................................. 13 Annex to Chapter 1-2 Annex to Chapter 1 Introduction Impressive scientific advances made during the 20th century which include systematization of medical education, increased research, improved diagnostics, novel and effective medicines and the growth of medical specialization has collectively transformed the field of gastroenterology and the management of acid-related diseases including peptic ulcer disease. Early in the century, access to the digestive tract was limited. Diagnostic and therapeutic resources were scarce. Clinicians were limited to blood counts, and urine analysis and a few chemical tests. This has changed dramatically. Today, comprehensive advancements have helped considerably in the overall and successful management of patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Some of these favorable advancements include:1 Diagnostic capabilities, including fiber-optic gastroscopy knowledge of risk factors, ability to perform biopsies, x-ray guided biopsy of the liver and colon, tests of hepatic and pancreatic functions, breath tests, quality x-rays, ultrasonography, computerized abdominal tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, Assessment of gastrointestinal motility and vascular status Increased understanding of the inflammatory cascade and gastric protective mechanisms, along with the discovery of multiple isoforms of the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme, have led to the development of potentially safer non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). More importantly gastroenterology has experienced tremendous growth in the understanding and use of therapeutic resources including blood transfusions, nutritional support services, sulfonamides, antibiotics, adrenocorticosteroids, immune modifiers, H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors. These agents have dramatically altered the management gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), management of peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and the prevention and treatment of non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-related gastrointestinal complications.2 Table 1 highlights some of the significant advances that have had an impact in the field of acidrelated diseases. Annex to Chapter 1-3 Annex to Chapter 1 Table 1: 20th century advances with significant impact on gastroenterology drug development and research1, 3 Gastrointestinal immunology; gut mucosal immune system Chemistry of digestive acids and bile acids Radioimmunoassays Endoscopic technological advances Nutrition (vitamins, nicotinic acid, folic acid) Genetic factors in gastrointestinal, liver and pancreatic diseases Increased support of research Improved diagnostic tools Growth of basic biomedical sciences and biotechnology Improved clinical studies and controlled trials Rigorous evaluation of medicines An enlarging body of scientific knowledge Technological improvements permitting safer and more precise human studies Increase public and private support of research and training Entry of young, scientifically trained physicians with a more scientific attitude toward clinical problems Controlled clinical studies and growth of evidence based medicine The establishment of professional and philanthropic organizations The growth and influence of academic medical research centers The growth and influence of scientific societies e.g. Helicobacter foundation, the gastroenterology research group, American society of clinical investigation, The American gatroenterology foundation The enlarging scientific communication network (journals, databases, electronic and computer systems From Surgery to Effective Pharmacological Therapies The last 35 years of the 20th century has witnessed a revolution in the treatment of acid-related diseases. Until then, there had been steady progress in the surgical approach to these ailments, beginning with Billroth and partial or total gastroectomy, and progressing to highly selective vagotomy in the 1960’s.4 On the other hand, bland diet and atropine were the only medical treatment options. Impressive advances in gastroenterology along with the introduction of effective treatments have changed this. Today, medical therapy is the first step in treating ulcer disease, with surgery reserved for complications and failure of that therapy. Recent advances in medical treatment have further reduced the need for operations with gastric surgery perhaps only being limited to emergent PUD and the treatment of gastric cancer. We are now 100 years past Billroth’s first successful gastroectomy. The first part of that century led to steadily increasing numbers of surgical procedures, whereas the second part has been marked by increasing understanding of physiologic factors, leading to lesser, but better directed operations.4 Annex to Chapter 1-4 Annex to Chapter 1 Research during the past 35 years into gastric acid related disorders and the development of agents that effectively suppress gastric acid represents a milestone in the management of these diseases. Numerous clinical studies have documented the safety and efficacy of these agents in proving rapid pain relief and improving ulcer healing and erosive GERD without the need for complicated surgical procedures. This section reviews some of the critical developments that have occurred over the past 3 decades in the management of acid-related disorders. The time line presented reveals how improved understanding and new insights have contributed to the evolution of drug therapy from antacids to histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), discovery of H Pylori to the introduction of proton pump inhibitors onto the market. The history and evolution of gastroenterology demonstrates the impressive progresses that have been achieved in terms of basic research, and pharmaceutical developments which has totally changed the management of PUD. In particular, the introduction of selective histamine receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors has made the medical control of acid secretion, including PUD, an effective means of therapy with less reliance on costly and complicated surgical procedures. These impressive advances highlight the successful intervention of effective pharmaceutical therapies with closure of a therapeutic gap.5, 6, 16 Based on the discovery of highly selective vagotomy and reduced acid secretion it was recognized that acid secretion is a regulated process. In 1963, Dr Black and his colleagues discovered that pharmacological inhibition of gastric acid stimulation would provide an alternative to surgery.5 Histamine had been discovered as a major stimulant to gastric acid stimulation and although histamine antagonists were developed for treatment of allergies, there were found to be too weak to provide any gastric acid inhibition. With a great deal of focused research during the 1960’s and 1970’s, the first selective histamine antagonist burimamide was developed and by 1977 cimetidine was launched as a therapy for peptic ulcer disease. Cimetidine proved to be a breakthrough in the medical therapy of PUD symptoms and was followed rapidly thereafter by other such H2RAS with similar efficacy. The discovery of the pharmacological inhibition of acid secretion by histamine 2 receptor antagonist (H2RAs) provided the first possible alternative to surgery. Furthermore, until recently GERD was considered a trivial problem with very limited pharmaceutical interest. However, over the past 10 years, GERD has received significantly more attention by industry and it is now considered a major market for antisecretory acid suppression agents.5 Despite effective medical therapy with H2RAs, it was found that although ulcers healed approximately 70% reoccurred after stopping therapy. It was not until 1983, when infectious organism Camplobactor Pyloridis (now called Helicobacter Pylori or H Pylori) was discovered which was thought to be responsible for the recurrence of peptic ulcer diseases. Rigorous research into this area, established that H Pylori is a causative agent for most peptic ulcers, with the exception of PUD caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Eradication of H pylori resulted in a cure for PUD and a sharp reduction in morbidity.1, 7 Annex to Chapter 1-5 Annex to Chapter 1 In treating acid related disorders it became evident that while acid affliction of the stomach and duodenum were suppressed by H2RAs gastro-esophageal reflux disease was more resistant. A new class of drugs-proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were launched onto the market which proved to be more effective in inhibiting acid secretion and targeting acid secretion, the H,K Atpase or acid pump. The discovery of omeprazole and its unique mechanism of action on the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) revolutionized the ability to inhibit acid secretion and control intragastric pH. All the current PPIs have the same core structure and are pro-drugs. With the addition of PPIs, approximately 70% of maximal acid secretion were effectively reduced and its addition to the H Pylori regimen further assisted in the rapid eradication of the infectious organism.5 Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) The term PUD generally refers to spectrum of disorders that includes gastric ulcer (GU), pyloric channel ulcer, duodenal ulcer (DU) and postoperative ulcers at or near the site of surgical anastomosis.8 Helicobactor pylori has been recognized as the main cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric mucosa-associated with lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). Although H. Pylori is an established cause of several gastric diseases mentioned above debate continues over whether it has any role in the etiology of disease outside the stomach.7,8,9 It is now believed that ulcer results from a complex interplay of acid and chronic inflammation induced by HP infection although exact mechanism has not been elucidated. H Pylori is associated with most cases of duodenal ulcer (DU). Other causes of DU are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin, NSAIDs etc. and tumors like Zollinger Allison syndrome. Most gastric or stomach ulcers are also associated with H Pylori. However, only a subset of infected persons develops peptic ulceration. The reasons for this are not known and it may be due to variation in host factors, bacterial factors or both. Infected persons have a 2- to 6-fold increased risk of developing gastric cancer and mucosalassociated-lymphoid-type (MALT) lymphoma compared with their uninfected counterparts. The role of H. pylori in non-ulcer dyspepsia remains unclear. Epidemiology Prevalence of H. pylori infection correlates with socio-economic status rather than race, with a prevalence of 80% in developing countries compared to prevalence of 20-50% in developed countries.7 In the United States the probability of being infected is greater for older persons, with prevalence rates greater than 50% in individuals older than 50 years and older. Minorities of varying age groups have a higher prevalence 40 to 50%, and immigrants from developing countries such as Latinos have prevalence rates greater than 60%. The infection is less common in more affluent Caucasians at 20% for individuals less than 40 years of age.10 Although most gastric ulcers are usually caused by H. pylori, reports from the US show that 30% of gastric ulcers can be related to aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs Annex to Chapter 1-6 Annex to Chapter 1 (NSAIDs).10 Most gastric adenocarcinomas and lymphomas occur in persons with current or past infection with H. pylori. In developing countries, the ulcer groups are smaller and the gastric cancer group may be larger. For example, in northern Brazil, gastric cancer is the most common malignancy in men.10 Western countries10 In general, the following statements can be made to summarize prevalence of H Pylori in Western countries: H Pylori affects about 20% of persons below the age of 40 years, and 50% of those above the age of 60 years. H Pylori is uncommon in young children. Low socio-economic status predicts H Pylori infection. Immigration is responsible for isolated areas of high prevalence in some Western countries. Developing Countries10 In developing countries, most adults are infected. H Pylori infection which occurs in about 10% of children annually between the ages of 2 and 8 years so that most are infected by their teens. It is evident from careful surveys that the majority of persons in the world are infected with H Pylori. H pylori can be cultured from the stools in most infected persons This is evidence that spread by fecal oral contact with infected persons is likely. In addition, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can detect H Pylori in dental plaque from 30% of persons with the gastric infection. However, this may be a less common source of transmission. Transmission Transmission is through oral ingestion, documented through vomitus, saliva or feces and possible through waster sources in developing countries. The exact mode of transmission of H. pylori stills remains elusive. Although H pylori may be eradicated with antibiotics, infection may persist unless specific combination of antibiotics and acid suppressing agents are used. Diagnostic Tests Infection with H pylori can be diagnosed by endoscopic biopsy (rapid urease testing, histological examination, culture or polymerase reaction) or by non-invasive methods (serology, urea breath test, or the detection of H pylori antigens in the stool. The choice of appropriate test is based on clinical situation. Therapy Management of PUD and treatment has changed dramatically. Treatment of PUD has evolved from dietary modifications and surgery to acid suppression with antacids, H2RAs, proton pump inhibitors and eradication of H Pylori infection. Prior to the development of H2RAs, patients were frequently managed as inpatients and surgery was common. Today the use of H2RAs and Annex to Chapter 1-7 Annex to Chapter 1 later PPIs have dramatically changed the management of PUD from in-hospital to a largely outpatient setting with reduction in the number of surgical procedures.11 Table 2 shows the currently approved agents for the management of acid –peptide diseases such as PUD and GERD. Histamine-2 (H2) blockers started coming in 1970s. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the new class of drugs that profoundly inhibit acid secretion and have been shown to be very effective in ulcer healing. Table 2. Currently approved agents for the management of gastric acid related diseases12, 13, 14 Therapeutic class Antacids Prokinetic agents Mucosal Protective agents Histamine-2 Receptor antagonists Proton pump inhibitors Agents Calcium carbonate Magnesium hydroxide Aluminum hydroxide Bethanechol Metoclopramide Domperidone Cisapride Sucralfate Alginic acid Cimetidine Nizatidine Ranitidine Famotidine Omeprazole Lansoprazole Pantoprazole Rabeprazole Esomeprazole Therapy for H. Pylori includes 1-2 weeks of a triple therapy of a proton pump inhibitor plus clarithromicin and either amoxicillin or metronidazole. Quadruple therapy of proton-pump inhibitor with bismuth subcitrate, tetracycline and metronidazole for more than a week is equally efficacious. 7 Table 3 shows the currently available therapeutic combinations that can treat PUD. Table 1 in the annex shows H Pylori regimens with associated cure rates. Annex to Chapter 1-8 Annex to Chapter 1 Table 3 Suggested regimens for the treatment of H. pylori infection15 Regimen PPI (lansoprazole 30 mg OR omeprazole 20 mg) + amoxicillin 1000 mg + clarithromycin 500 mg (each drug given twice daily for 2 wk) PPI (omeprazole 20 mg OR lansoprazole 30 mg) + metronidazole 500 mg + clarithromycin 500 mg (each drug given twice daily for 2 wk) RBC 400 mg + clarithromycin 500 mg + amoxicillin 1000 mg OR metronidazole 500 mg OR tetracycline 500 mg (each drug given twice daily for 2 wk) Bismuth subsalicylate 525 mg q.i.d. + metronidazole 500 mg t.i.d. + tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d. + PPI (omeprazole 20 mg q.day OR lansoprazole 30 mg q.day) (each drug given in the dosage and frequency indicated daily for 2 wk) Bismuth subsalicylate 525 mg q.i.d. + metronidazole 250 mg q.i.d. + tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d. + H2-receptor antagonist (each drug given in the dosage and frequency indicated daily for 2 wk with the H2-receptor antagonist continued for a further 2 wk) ** Rbc: ranitidine bismuth citrate A number of studies have documented the dramatic decline in surgery for PUD since 1975. The studies reviewed below from Europe and the US have demonstrated the widespread impact of pharmaceutical interventions. Today, operative treatment is limited to a small proportion of ulcer patients who have complications or those who do not respond to medical treatment. In this era of very potent anti-secretory agents and increasing knowledge about the role of H pylori, surgery for routine PUD is of only historic significance. Surgery however may have a greater role in complicated ulcer disease involving bleeding, perforation and obstruction. Time Trends in Peptic Ulcer Surgery – Pharmaceuticals Closing the Surgical Gap Time trends in peptic ulcer surgery from 1956 to 1986 based on a nationwide survey in Sweden report that elective surgical operations steadily declined from 72.1 per 100,000 to 10.7 per 100,000 inhabitants. Also, the operation rate for perforation decreased by 50% from 12.8 to 6.4 per 100,000 inhabitants. Results of the nation wide Swedish survey conclude that there had been a dramatic decline in elective peptic ulcer surgery with the introduction of new technologies and effective therapies.16 Results from a report evaluating the incidence of ulcer disease among surgical patients in a clinic in Germany conclude that the incidence of surgical operations increased after 1949 and reached a peak from 1964 to 1978, but gradually decreased thereafter.17 A study from Norway assessed the incidence of operations for peptic ulcer disease or related complications from 1975 to 1989 in people older than 15 years of age in a population of 100,000 inhabitants. Results revealed that the number of elective surgical procedures decreased significantly by 72% from 1975 to 1989. The greatest reduction in surgery was Annex to Chapter 1-9 Annex to Chapter 1 related to duodenal ulcers. The incidence for acute operations also decreased by 35%. Authors of the study conclude that the dramatic reduction in surgical interventions can be attributed to the introduction of H2RAs in the 70’s and the more successful pharmacological management of peptic ulcer disease.18 An evaluation from the department of Surgery from Texas was conducted to determine the effects of the pharmacological and endoscopic treatment of PUD and the operative management of PUD over the past 20 years. Results of the study showed that the number of gastrointestinal operations decreased by 80%, however the number of gastric cancer operations remains unchanged. Moreover, the evaluations showed that not only were surgical interventions markedly reduced but the prevalence of bleeding, perforation and obstruction were also reduced. Authors concluded that the improved pharmacologic and endoscopic treatments have progressively curtailed the use of operative therapy for PUD. Elective surgeries were rarely indicated and emergency operations were less common.19 A study from Finland assessed the incidence of surgery, hospital admissions and mortality of PUD from 1972 to 1999. Results from the study confirmed that the medical therapy of PUD had improved significantly over the past 20 years with the introduction of effective agents such as H2RAs and PPIs, as well as the eradication regimens for H Pylori. During the 1990’s, there was a 3-fold increase in the consumption of antisecretory agents as well as an 8fold increase in NSAIDs use. Results of the study showed that there as an 89% reduction in elective operations (from 1987 to 1997); the number of emergency operation for bleeding ulcers increased by about 44% during the same time period, and the annual hospital admissions increased by 79%. This increase was attributed to bleeding ulcers and complication in elderly women. Mortality rates also increased 74% from ulcer perforations and hemorrhages. Authors of the report concluded that the increase in emergency surgical procedures, hospital admissions and mortality reflect the demographic changes and the increased consumption of NSAIDs among the elderly in particular. Furthermore, regardless of the increased emergency surgical operations elective operations for PUD had declined and are not required today.20 A retrospective study was conducted in a community hospital in the United States to evaluate the impact of H2RAs on the surgical treatment and outcome of patients with PUD before and after the introduction of H2RAs. Two groups were reviewed: group 1 from 1971 to 1973 and group 2 from 1981 to 1983. Differences between the two groups were noted. Indications for emergency operations were predominant for group 2 and there was reduction in elective surgeries from 75% to 55% for group 2. The authors conclude that the introduction and use of H2RAs have changed the surgical treatment and outcome of patients with PUD.21 A report from Poland reviewed the indications for surgeries performed on PUD from two time periods, 1977 to 1981 and 1992 to 1996. What is specific for this evaluation is the delayed entry and clinical use of antisecretory agents which were available in the late 1980’s. Results of the study showed a marked reduction in operation for PUD for the second time period. There were more women of an older age who were operated on for bleeding, intractable and perforated ulcers in the latter period. Based on the results authors of the study conclude that the course and management of PUD has changed as the number of patients undergoing surgery has declined due to the introduction of new effective therapies, Annex to Chapter 1-10 Annex to Chapter 1 and to a lesser degree it can be attributed to other factors such as lifestyle changes, smoking and diet.22 Past and Current Research There has been little advancements in the therapy for H Pylori, however intense research continues in this area and investigation of H pylori continues to provide new insights into the pathogenesis of this infectious agent. Clinically, there is considerable debate but little new information regarding H. pylori and NSAID-induced gastric damage, its role in non-ulcer dyspepsia and its relationship with esophageal disease. Animal models have been developed and have been used extensively to study the immune response of H pylori in order to develop suitable vaccines. Animal models continue to provide important information regarding the pathogenesis. More importantly the recent knowledge and availability of genomic sequences for Homo Sapiens and H pylori has stimulated basic research into dissecting the involvement of H Pylori with gastric malignances at the molecular level. This work is providing new directions for further research with eventual clinical application. Other areas of study include the following7: Prophylactic oral immunization with recombinant H Pylori urease and escherichia coli. H Pylori and its association with extragastric diseases such as hepatobiliary disease, pancreatic cancer, and even arthrosclerosis. H Pylori virulence factors. VacA is a gene of H Pylori. H Pylori stains expressing large amounts on VacA are associated with a higher incidence of PUD. Growth and metabolism of H Pylori is also being studies to identify therapies to better target and eradicate the infection. PPI and H2Ras are currently the most effective pharmacological treatments for PUD when used in combination with antibiotics and acid reflux disease. Despite the efficacy of these agents, there is still a potential for further improvements in pharmacotherapy. Some areas that have been identified include the following9: Faster onset of action for complete acid suppression, improved duration of efficacy and combination therapies which can improve compliance. A number of novel drugs are also under investigation for GERD which may be promising for PUD. These include transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation-reducing agents, serotonergic agents, potassium-competitive acid blockers, mucosal protectants, histamine H3 agonists and anti-gastrin agents. If one or more of these groups prove to effective, additional options will become available to clinicians to manage acid-related diseases.23, 24 Annex to Chapter 1-11 Annex to Chapter 1 Table 3 New therapeutic agents for acid-peptide diseases23 Potential novel targets Proton pump inhibitors Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation reducing agents (TLESR) Serotonergic agents/prokinetics Potassium-competitive blockers Histamine H3 agonsists Antigastrin agents Examples Ilaprazole Tentaprazole Current development status Phase II Phase II Preclinical Tegaserod Phase III AZD0865 CS-526 Revaprazan Soraprazan R-alpha -methylhistamine Anti gastrin vaccine Itriglumide Z-360 Phase II Phase I Phase II Phase II/III Preclinical Phase I Phase I Phase II Antacids, which were once considered an old-fashioned acid suppression therapy, may increase esophageal pH to for up to 90 minutes. There is new interest now in developing combination over the counter therapies of H2Ras plus antacids. The strategy is aimed at allowing for prompt treatment of ‘heartburn’ with the prevention of subsequent episodes for several hours. At present a combination product is not available but given the over the counter market potential for low dose H2RAS and the competition from PPI going over the counter development and availability of these agents is not far off.25 Conclusion Gastric acid related disorders including peptic ulcer disease are common clinical problems. Important advances have occurred over the past 35 years that have improved our understanding of these disorders as well medicines that have significantly improved the management of acid related disorders which have reduced the need for surgery. We now know that although H Pylori plays a critical role in the pathogenesis and relapse of PUD, effective gastric acid suppression is required in addition to antibiotic therapy for prompt ulcer healing and H pylori eradication. Gastric acid also plays a pivotal role in the development of GERD. Control of gastric acid therefore remains the cornerstone of effective management of these disorders. Treatment of gastric acid related disorders including PUD has evolved from dietary modifications and surgery to acid suppression with antacids, H2RAS, proton pump inhibitors and eradication of H Pylori infection. Major advances of gastroenterology during the past century has been the application of new scientific knowledge, market potential, technology, and controlled clinical trials to the study of Annex to Chapter 1-12 Annex to Chapter 1 gastrointestinal problems. Pharmaceutical commitment to research and development of novel effective therapies complimented with an array of dosage forms IV, tables, capsules, suspensions, sustained release compounds have also contributed to the progress in this field. As we proceed biology, biotechnology, and genomic information will challenge the field of gatroenterology to utilize this information, strengthen its research efforts and apply the knowledge towards more effective therapies for gastrointestinal and digestive diseases. Furthermore, the dramatic decline in surgery for PUD demonstrates that pharmaceutical progress can significantly change the practice of medicine. It is reasonable to hope that similar pharmaceutical advances could reduce the need for other costly surgical procedures such as coronary artery or joint replacement surgery. References http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/407942. Kirsner JB. Review Article: 100 years of American Gastroenterology: 1900-2000. Last accessed June 6, 2004. 1 http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/424446_1 Feb 2000 - Philip Schoenfeld, MD, MSEd, MSc, provides an update on the medical management of gastric acid secretion, with an emphasis on clinical applications and comparative pharmacology of new agents Last accessed June 6,2004. 2 http://www.medlina.com/gastroenterology_organizations.htm. List of gastroenerology organizations. Last accessed June 6, 2004. 3 Weil P, Buchberger MD. From Billroth to PCV: A century of Gastric Surgery. World J Surg. 1999; 23:736742. 4 Sachs G, Shin JM, Vagin O et al. Current trends in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal disease. Best Practice and Resercag Clinical Gastroenterology. 2002; 16 (6): 835-849. 5 Earnest DL, Robinson M. Treatment Advances in Acid Secretory Disorders: The promise of Rapid Symptom Relief with Disease Resolution. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999; 94 (Suppl 11): s17-s24. 6 7 Moss S Sood S. Helicobacter Pylori. Current Oppinion in Infectious Disease 2003, 16:445-451. 8 http://www.diagnosishealth.com/ulcer.htm. Diagnosis Health. Last accessed June 6, 2004. 9 http://www.cdc.gov/ulcer/md.htm. Center for Disease Control. Last accessed June 6, 2004. 10 http://www.helico.com. The Helicobacter Foundation. Last accessed June 6, 2004. 11 Smooth DT, Go MF, Cryer B. Peptic Ulcer Disease. Primary Care. 2001; 28(3): 487-499. Maton P. Profile and Assessement of GERD Pharmacotherapy. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2003; 70: Suppl 3: s51-70. 12 Brunner G. Proton Pump Inhibitors are the Treatment of Choice in Acid –Related Disease. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1996; 8: suppl 1: s9-s13. 13 Webb D. New Therapeutic Options in The Treatment of GERD and other acid-peptic Disorders. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2000; 6: suppl 9: s467-s475. 14 Annex to Chapter 1-13 Annex to Chapter 1 Colin W. Howden, CW, Hunt R. Guidelines for the Management of Helicobacter pylori Infection. American Journal of gastroenterology. 1998 93 (12): 2330-2338. 15 Gustavsson S, Nyren O. Time Trends in Peptic Ulcer Surgery, 1956 to 1986. A Nation Wide Survery in Sweden. Ann Surg. 1989; 210 (6): 704-9. 16 Braun L. Incidence of Ulcer Disease Among Patients of the Detmold Surgical Clinic 1949-1989. Zentralbl Chir. 1991; 116(9):551-8. 17 Haaverstad R, Moen OO, Kannelonnings KS et al. Ulcer surgery and anti-ulcer agents. Changes in surgical activities and sale of anti-ulcer agents in Nord-Trodelag 1975-1989. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1994; 20 (11): 904-7 18 19 Schwesinger WH, Page CP, Sirinek KR et al. J Gastrointestin Surg. 2001; 5(4)438-43. Paimela L, Paimela I, Myllykangas-Luosujarvi R, Kivilaakso E. Current Features of Peptic Ulcer Disease in Finland: Incidence of Surgery, Hospital Admissions and Mortality for the Disease During the Past Twenty-Five Years. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002; 37 (4): 399-403. 20 Scheeres DE, DeKryger LL Dean. Surgical Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease Before and After Introduction of H2 Blockers. 1987; 53 (7): 392-7. 21 Janik J, Chwirot P. Peptic Ulcer Disease Before and After Introduction of New Drugs –A Comparison from Surgeon’s point of View. Med Sci Monit. 2000; 6(2): 365-368. 22 Vakil K. Review article: New Pharmacological Agents for the Treatment of Gastro-esophageal Reflux Diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004; 19: 1041-1049. 23 Lanas L, Santolaria S. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease : Current agents and future perspective. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2001, 7: 1-18. 24 Robinson M. Drugs, Bugs and Esophageal pH Profiles. Yale journal of Biology and Medicine 1999;72:169-172. 25 Annex to Chapter 1-14