Non-Renaissance case study report

advertisement

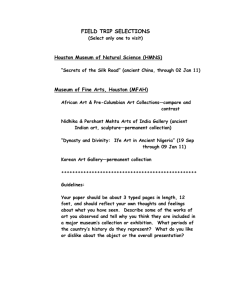

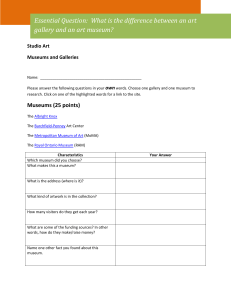

Capturing the Outcomes of Hub Museums’ Sustainability activities Non-Renaissance case study report March 2011 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 Environmental sustainability at the Natural History Museum Innovation points Context What happened and how Future plans Success factors Research sources 4 4 4 4 7 8 8 3 Mainstreaming sustainability throughout the National Trust Innovation points Context What happened and how Future plans Success factors Research sources 10 10 10 11 13 14 14 4 Mobilising networks and contacts at the Whitechapel Gallery Innovation points Context What happened and how Future plans Success factors Research sources 15 15 15 16 18 19 19 5 Project Hope at the Watts Gallery Innovation points Context What happened and how Future plans Success factors Research sources 20 20 20 21 22 23 24 1 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial 1 Introduction The following four in-depth case studies demonstrate best practice for sustainability outside of the Renaissance programme. The case studies provide some indication of how the wider sector is progressing with the sustainability agenda, and they add further examples of best practice to the case studies of Renaissance projects. The case studies were chosen in close consultation with the MLA and the Advisory Group. They are: • Environmental sustainability at the Natural History Museum • Mainstreaming sustainability throughout the National Trust • Project Hope at the Watts Gallery • Income generation at the Whitechapel Gallery These four case studies were selected to represent: • Environmental and economic sustainability, as volunteering is well documented by existing research (the exception is the National Trust case study, for which it was felt to be appropriate to examine the Trust’s comprehensive ‘triple bottom line’ approach); • Innovation in terms of the interventions made and the partners and funding sources accessed; • A variety of sizes of institution: very large (Natural History Museum, 4,000,000 visits per year) to small/medium (Watts Gallery, 25,000); • A variety of statuses: one national museum, two independent institutions and one national charity operating multiple sites; • The museum sector as well as relevant parts of the arts sector; • Projects which read across to specific Renaissance case studies: for example estate improvements at Natural History Museum read across to the two London Sustainable Museums projects, while the transformation of Watts Gallery reads across to the transformation of the Russell-Cotes; • More general transferability to the wider museum sector. Each case study follows a standard template. This specifies: • 2 Innovation points, i.e. what the institution is doing which is innovative The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial • Context for the interventions made • What happened and how it was achieved • Future plans to further develop sustainability approaches • Success factors according to relevant project leads • Research sources used to prepare the case study While each institution profiled is unique, some shared success factors that emerge from the case studies: • Leadership is inspiration plus perspiration: the Whitechapel and Watts Gallery Directors seem to take a particularly hands-on approach to fundraising and income generating events. • Consult and engage staff to break down routine rigidities, examples being the NHM’s Green Group and Green Publishing Group and the staff surveys that informed NT’s Going Local strategy; • Take a fresh look at assets, working with outsiders and ‘loose tie’ networks. Watts Gallery’s Project Hope was masterminded by a new Director; the Whitechapel is mobilising its capital campaign contacts for Future Fund and mobilises its art world contacts for the Collecting Contemporary Art course; and the NHM is working closely with its suppliers and licensees, who now generate ideas for new projects. • Be willing to take risks and encourage experimentation by staff. The NHM was quick to sign up to and utilise ESCo, ISO 14001 and the CIBSE 100 Days initiative while Whitechapel’s ArtPlus events and Limited Editions. The NT has embarked on a massive devolution of responsibility to local managers within ‘Going Local’. • Write sustainability into decision-making to create legitimacy and new routines. NHM’s commitment is firmly embedded in its policies, and departmental energy targets, and the NT’s ‘Going Local’ policy is very explicit in its pursuit of triple bottom line sustainability. 3 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial 2 Environmental sustainability at the Natural History Museum Innovation points • ‘Early adopter’ from 1990s onwards leading to the Museum’s present wide and deep engagement with environmental sustainability; • Cross-departmental programme influencing virtually all aspects of the museum, from estate management to exhibition design to retail; • Exploitation of unusual funding sources: Invest To Save and ESCO; • Collaboration with other South Kensington cultural institutions. Context In 2003 the Museum became the first in the UK to receive ISO 14001 accreditation. This recognises the pioneering work to green the Museum that gathered momentum through the 1990s, and it provides a framework for the ongoing efforts to drive up energy efficiency. The Museum’s interest goes beyond ‘off the peg’ and typical solutions (though it does use these where relevant). It is keen to discover innovative new ways to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions to the lowest practical levels, whilst meeting the operational standards of the museum. This necessitates working within the constraints posed by the Grade I listed main building: clearly, solar and wind energy, or rainwater harvesting are not possible. The Museum also has to manage a degree of unavoidable energy consumption, for instance to maintain the cool temperatures needed within the Darwin Centre to conserve the fragile insect and plant collections. The Museum’s current DEC rating is ‘D’, an improvement on its previous ‘E’. What happened and how Estates In 2006 the Museum was the lead partner for the South Kensington Cultural and Academic Estate’s successful bid for HM Treasury’s Invest to Save funds, to reduce carbon emissions across the estate (the Museum plus Imperial College, the V&A and Science Museums, and the Royal Albert Hall). The £2.85 million funded a masterplan to help all the partners to reduce their carbon emissions by seven to ten percent by 2010. The Museum’s main intervention under the masterplan was replacing its outdated and expensive heating system with a new CHP system, shared with the V&A. The deal was structured as an energy service company (ESCo) with Vital Energi. Under the terms of the ESCo, Vital Energi designs, builds, finances and operates the new system for 15 years while the Museum is guaranteed to save at least 4 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial £579,000 annually over the 15- year contract. This is possible as CHP typically achieves 80% fuel efficiency compared to 30% for conventional power generation and draw-down. By securing investment from Vital Energi, the Museum also saved the £3 million that it had set aside to replace the old system. Chillers attached to the new CHP system The Museum treated the construction of the £78 million Darwin Centre, as a further opportunity to develop sustainable approaches. When the Museum’s old entomology building was demolished, around 95% of the materials were re-used in the Darwin Centre and elsewhere. The Centre consumes a large amount of energy, which is unavoidable, but it is designed to be as efficient as possible. The concrete ‘cocoon’ structure acts as a heat reservoir to insulate against external temperature changes. This helps to stabilise the environment and to reduce use of heating and air conditioning. The rooms that do not have people in them very often are allowed to have a variable temperature, so energy is not wasted on heating or air conditioning them unnecessarily. To avoid over-heating, the glazing on the west side of the building is etched, to reduce the amount of the sun’s heat that gets inside. Accompanying these major capital works is a focus on back office areas and staff behaviour, for example to maximise recycling. In 2007 the Museum joined the Chartered Institute of Building Services Engineers’ (CIBSE) initiative ‘100 days of Carbon Saving’. Each year, during the 100 days, employees are encouraged to switch off lights and appliances when not in use. It leads to reduced energy use each year. 5 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial Suppliers and commercial operations The Museum works closely with its suppliers and commercial partners to collectively improve their sustainability. One example is a partnership with Philips that replaced 60 external floodlights with 30 LED units, which are far more energy efficient. An unusually thorough approach is taken to embedding sustainability within retail and licensing operations. The Museum has typically taken the lead in setting the standards it wants to achieve, but its suppliers and licensees now also come forward with new ideas. Some of the improvements made include reducing packaging, moving from plastic to paper bags, coordinating orders and deliveries with the neighbouring Science Museum, and using recycled paper for virtually all of the 80,000 postcards the Museum sells each year. The Museum occasionally vetoes products which would be successful but have poor environmental credentials, such as PVC-based Oyster card wallets. But it also has to meet its commercial imperatives: for example organic cotton T-shirts were discontinued as shoppers did not want to pay the £5 extra that these cost over less sustainable Tshirts. Benugo was selected to be the Museum’s catering partner, partially because of its commitment to sustainability. Public programmes Claire Methold, the Museum’s Environmental & Sustainability Officer, is quick to point out that the museum’s mission is to “maintain and develop our collections and use them to promote the discovery, understanding, responsible use and enjoyment of the natural world” –it is not a “museum of climate change” per se. Nonetheless the Museum does address environmental sustainability issues within its exhibitions and public programmes, as follows: • Permanent exhibitions – the ‘Earth Today and Tomorrow’ gallery on themes of sustainability and living within the Earth’s resources, and the Climate Change interactive wall exhibit within the Darwin Centre. • Temporary exhibitions – often include a panel discussing environmental aspects of the exhibition topic (for example declining fish stocks, in The Deep) or the museum’s environmental credentials. The Museum trials new sustainable materials for exhibition construction and recycles where possible (for example, panels are re-used each year for the Wildlife Photographer of the Year show). 6 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial • Website – which contains several pages dedicated to climate change, as well as downloadable versions of the Museum Environmental policy and the Museum Energy & Emissions policy. The Climate Change wall in the Darwin Centre Future plans The Museum’s successes have been recognised by: • CIBSE Best Carbon Saving campaign award in 2008; • Platinum Award in the Mayor of London's Green500 carbon reduction scheme in 2009. This was due to the CHP scheme and to the museum’s success with the CIBSE initiative; • Leading role in funding bids (particularly, the Invest to Save bid) • Two DCMS ‘climate change’ case studies about the museum. The Museum’s future plans include: • Gradually replacing out-of-date plant with energy efficient alternatives; • Continuing to replace conventional lighting with LEDs at the South Kensington site; • An ESCo for the other Museum sites in Tring and Wandsworth; • Continuing to raise awareness with suppliers and licensees. 7 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial Success factors • Buy in at the top: the Director and the Director’s Policy Advisors take an active interest in making the museum greener. The Board of Trustees receives energy management reports within the main budget reports. • Explicit responsibilities: are written into the Museum Energy & Emissions, and Environmental, Policies. These show clear lines of responsibility down from the Directors Group to all departments. • Passion of staff: especially in the Estates team, who lead and coordinate environmental sustainability efforts. Claire Methold’s responsibilities include: ◦ Internal audits with each department; ◦ Working with the procurement team on purchases; ◦ Advising on travel options and cycling (the Museum also runs two hybrid cars in its fleet); ◦ Data collection and management. • Trickle down: Museum staff are engaged from the outset in their induction talk, and then kept in the loop via intranet postings. The Environmental Focus Group represents all departments, and turnover of its members is encouraged in order to reach beyond the self-selecting and to achieve wider representation. There is now a spin-off Public Engagement Green Group that focuses on publishing and exhibitions. • Trickle out: to the Museum’s suppliers, neighbours and sponsors. • Attention to detail: as illustrated by the current discussion on whether the museum logo’s white background restricts the grade of recycled paper which can be used. • Eyes open: for external networks and groups to join, such as the Mayor of London’s Green500 scheme, or the government’s Carbon Reduction Commitment (CRC) and Energy Trading schemes. Research sources • Interview with Claire Methold, Environmental & Sustainability Officer for the Natural History Museum; • Interview with Jeremy Ensor, Head of Retail and Licensing for the Natural History Museum; • Combined Heat & Power: Natural History Museum DCMS Climate Change Case Study 003, accessed via the DCMS website; 8 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial • 100 Days of Carbon Savings at the Natural History Museum DCMS Climate Change Case Study 004, accessed via the DCMS website; • Natural History Museum Tri Generation Case Study, accessed via the Vital Energi website; • Museum Environmental policy and the Museum Energy & Emissions policy, accessed via the Natural History Museum website. 9 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial 3 Mainstreaming sustainability throughout the National Trust Innovation points • An all-round strategic organisational approach to ‘triple-bottom line’ sustainability through the Trusts’ ‘Go Local’ strategy for 2010-2020 • Groundbreaking solutions to adapting renewable energy technology to the conditions of historic buildings • Combination of strong leadership drive with devolving central control and responsibilities Context The National Trust has a strong track record for advocacy and action on environmental sustainability. This is exemplified by the Trust’s target of reducing its carbon emissions from energy use by 45 per cent over the next ten years, which exceeds the Government target of 34 per cent. The Trust increasingly locates its commitment to the environment within a comprehensive ‘triple bottom line’ approach that also embraces the social and economic aspects of sustainability. This new approach goes hand in hand with a transition to a devolved operating model under which the corporate sustainability goals will be delivered by each property manager developing their own local solutions. ‘Going Local’, the strategy for the Trust over 2010 to 2020, makes this explicit. The strategy calls for "a new mindset and a new way of working" while reemphasizing a reconnection with the original vision for the Trust. Going Local’s main themes are: • Sense of Belonging: increasing access for existing members and nonmembers and offering greater involvement in Trust decision-making; • Time Well Spent: championing the simple pleasures of life via more opportunities to access Trust land, volunteer and grow food – and working with neighbours to use energy and resources efficiently; • Bringing places to life: creating fresh approaches to interpretation and activation of Trust sites thereby increasing user enjoyment. Above all, Going Local seeks to put Trust properties back at the centre of communities. Director-General Fiona Reynolds explains: “In the end, if we're to truly fulfil our original, radical purpose, we have to reach out in this way – to local residents, to people who feel the National Trust isn't for them. We have to make contact with people in a new way." 10 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial What happened and how Each National Trust asset is unique and – under Going Local – is managed to respond to its unique needs and opportunities. This research focuses on three Trust properties that exemplify the Trust’s approach to sustainability, and that might suggest lessons for museums. Dunster Castle: PV cells on a Grade I building The Trust will meet its carbon reduction target by cutting energy use by 20 per cent while introducing micro and small-scale generation using wood fuel (some sourced from its own estates), solar, heat pumps, hydro and wind. The Trust expects most of its schemes to break even over the next 10 years, helping to reduce its £6 million annual energy bill. Dunster Castle in Somerset is the first Grade I listed building the Trust has installed solar panels on. Sited discreetly on a south-facing roof, the 24 panels provide electricity to power 100 low-energy light bulbs. Rob Jarman, then the Trust's head of sustainability, explains: "These panels will demonstrate how we can harness renewable energy even from hugely important conservation sites without affecting their special character." The main challenge of the project was to find a solution for safely mounting the PV cells on the roof of Dunster Castle. Installing the cells directly would have required making holes in the lead roof (which could have potentially caused leakages). Instead, the cells were mounted on the parapets but – given the Grade 1 listed status – this required approval from English Heritage, which was ultimately received. Dunster Castle joins around 140 other renewable energy projects at Trust properties around the country. Together they represent a valuable learning resource for managers of other historic sites. According to Sarah Staniforth, Historic Properties Director at the National Trust, the most important lesson is that – while often challenging – it is possible and important to find environmentally friendly solutions and to use renewable energies in a way that minimises the impact on historic buildings. Seaton Delavel: community in the driving seat One of the National Trust's newest acquisitions, Sir John Vanbrugh’s Seaton Delavel Hall is probably the finest surviving example of the English Baroque. The acquisition was unique: it came about only after the trust had consulted 100,000 people, and when locals had raised nearly £1m of the £3m needed. In all, more than 11,000 local people (many not Trust members) came to four fundraising 11 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial events that they themselves organised. The community is also influencing the plans for Seaton Delaval Hall’s future. These include developing, over time: • Exhibitions and performances in the Main Hall, inspired by the Delaval family’s love for drama, music and practical jokes; • A Fourth Plinth-inspired competition where groups and individuals can bid to take over the Salon for a temporary exhibit or activity; • The Walled Kitchen Garden to include gardening plots used by local schools, community groups and visitors; Liz Fisher, Assistant Director of Operations, sums up the approach: "Basically, we're going to open and see what happens. In the past we would have come in, a big national organisation with a big high-level cultural project. Here the community will help decide on practically everything. This is going to be a work in progress for 20 years." The project is an ideal fit with the ‘Going Local’ strategy, in particular with regards to building support and a sense of ownership for the local property within the community. For the Trust, encouraging local membership is a way of ensuring a more sustainable future of their local properties. While it is too early to draw conclusions about the long-term take-up and engagement, within the time since its acquisition, Seaton Delavel Hall has emerged as a real community space – a ‘local village hall’. To-date, the Trust’s experience of properties with strong community leadership has been very positive. Striking a balance between providing access and ensuring that the property’s conservation needs are met is obviously relevant. However, Sarah Staniforth does not believe that incorporating innovative, community driven ideas for animating the property is more challenging than in cases where programmes are conceived by the property manager. Attingham Park: volunteer-powered restoration The 18th century house and estate are both undergoing conservation works, for example to restore the walled garden and laundry house as well as interiors within the main house. Volunteers are playing a key role in all works, alongside experts and Trust staff. Some 40,000 volunteer hours were donated in 2010, which is equivalent to over 20 full time staff. The volunteer positions being advertised at the time of writing illustrate the range of skills that are being employed: front of house staff for the shop and cafe, a cartoonist and calligrapher, several education and event roles; as well as outdoor activities that range from managing fishing licenses to hedge-laying, coppicing and helping to start a firewood business on-site. 12 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial The success of attracting and managing such a large pool of over 300 volunteers at Attingham Park is primarily driven by the property manager. Communicating the value of volunteers and making them feel as an integral part of the organisation has been a key factor in ensuring a rewarding experience for both volunteers and other staff in the organisation. Compared to other cultural heritage organisations and museums, Sarah Staniforth feels that the National Trust has overcome old preconceptions (e.g. volunteers taking away paid employees’ jobs) many years ago. Rather, volunteers are seen as a great resource to the Trust, much enhancing the property’s capacity, but who also need to be invested in through training and support. Volunteers are also considered as part of the organisation’s wider thinking around what is called the National Trust’s ‘supporters’ journey’, which is conceived as a continuous progression from visiting via membership to volunteering, and beyond this to becoming a financial supporter, donor or legator. Although inevitably, people don’t always follow such a linear progression pathway (e.g. not all volunteers are members), building loyalty between supporters and the National Trust is a key objective of the organisation’s thinking around their sustainable future. Future plans Going Local ushered in a radical restructuring at the Trust during 2010. Under the new system, property staff and volunteers are free to interpret how best to ‘go local’. This means exploring the uniqueness of their property and its special value to the community, bringing the property to life and engaging people more deeply in what happens there. The business plan for each property is generated by its property manager then agreed with regional Assistant Directors (for example, 75% of property visitors report a very enjoyable experience, or growth in local membership). In all over £35 million worth of budget is transferred away from the Trust’s central office and to property managers. The central office and radically slimmed-down regional teams will continue to supply ‘back office’ functions like financial management, IT, legal services and specialist conservation advice. Its experts now act as consultants to the property teams. According to Sarah Staniforth, the process of increasing the ownership of property managers – in particular in view of making the properties more sustainable – is ‘transformational’. Inevitably, there are differences in terms of the success of this process to-date, but ‘all the stepping stones are now in place and the direction of travel is clear for everyone.’ 13 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial Success factors The key success factors for the Trust’s new approach to sustainability under Going Local are: • An strong leadership approach by the Executive Team (including Fiona Reynolds, Sarah Staniforth and the appointment of the Sustainability Director post) and the conviction that it is not enough to rely on ideas being developed bottom-up • Focus on triple-bottom line approach to sustainability and property managers’ awareness of the importance of social and environmental sustainability, in addition to economic performance. • Innovation ideas and the will of local managers to engage with the sustainability agenda • Risk taking: devolve central control and responsibility in order to drive the Going Local strategy and the recognition that in order for property managers to be innovative, they need to take risks but also have the assurance that they are ‘allowed to make mistakes’ • Embedding sustainability within internal decision-making, for example as one consideration for the Project and Acquisitions Group (which operates at both national, regional and local levels of the Trust) • Making sustainability part of the visitor experience: show the technologies working and provide tips for visitors’ own homes. Research sources • Interview with Ben Cowell, Assistant Director for External Affairs for the National Trust; and Sarah Staniforth, Historic Properties Director for the National Trust • Going local – Fresh tracks down old roads – Our strategy for the next decade, National Trust, 2010; • Energy – Grow Your own, National Trust, 2010; • How the National Trust is finding its mojo, The Guardian, 10 February 2010; • The 1.000 year old castle fighting climate change, The Guardian, 7 February 2008 • Solar panels and wind turbines on National Trust properties, the Telegraph, 11 February 2010. 14 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial 4 Mobilising networks and contacts at the Whitechapel Gallery Innovation points • Commercialising curatorial expertise to run short courses; • Inviting artists to create and donate bespoke works for sale; • Appealing beyond art enthusiasts to music, dance and poetry; • Building an endowment to provide a measure of budget stability. Context The Whitechapel Gallery re-opened in 2009 after an £13.5 million expansion that almost doubled its gallery space. As a result of the expansion, visitor footfall increased by 120 per cent. The Gallery was founded to bring art to the people of East London. It remains committed to free entry and to offering learning opportunities in what remains a very deprived area. The Gallery is also energetically developing earned income streams and fundraising to meet the cost of its expanded operations. It is making particularly effective use of its networks and many contacts around the East London art world. This means encouraging people who already have a relationship with the Gallery to contribute more regularly, over a longer period, and via a greater range of opportunities. At the heart of this are the Gallery’s 2000 Members and 200 Patrons (many of whom joined in the recent recruitment drive post-expansion). The Member and Patron schemes are particularly important as they provide the opportunity to support the Gallery in lieu of paid admission. Membership costs are graduated to enable a wide range of people to be involved, including those getting a foot on the ladder – students and practising artists pay just £20. Many of the Gallery’s other products are discounted for Members to encourage them to start supporting the Gallery in multiple ways. In parallel, the Gallery is also putting its networks ‘to work’ to develop further products that the Gallery can sell, and to put on fundraising events. This case study focuses on four specific initiatives which are both innovative, and might be successfully adapted for a museum context. 15 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial The expanded Whitechapel Gallery on Whitechapel High Street What happened and how Collecting Contemporary Art course This short course is designed to share the Whitechapel’s expertise with prospective art collectors. The course has run successfully for several years, though it remains a rare example of a cultural institution commercialising its curatorial expertise in this way. The course capitalises on the Whitechapel’s status as a respected ‘neutral’ venue (i.e. it has no commercial interest in collectors’ purchases); as well as its role as a hub at the heart of the East London art world. This means that the Whitechapel can introduce course participants to a wide range of its contacts. Each session focuses on a different perspective within the art world: curators, artists, dealers, collectors and auctioneers. The culmination of the sessions is a guided tour of the Frieze art fair, one of the world’s leading art fairs, which takes place in London every October. The participants learn in a small group and benefit from the personal involvement of the Whitechapel’s Director Iwona Blazwick OBE. The course is priced at £650 and so targets those with a serious interest in collecting. The Whitechapel sees the course as not just a cash generator but as an opportunity to build closer 16 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial relationships with the participants, who may for example become Patrons or donors. The Gallery also offers a one day course on curating, collecting and handling contemporary art, again featuring the Director alongside a range of art world perspectives. It is priced at £150 including lunch. Limited Editions £2.5 million of the £13.5 million expansion budget was sourced from an auction of artworks donated by artists. Since the expansion, the Gallery has focused on building its Limited Editions, affordable artworks that are created by exhibiting artists and sold to benefit the Gallery. The incentive for exhibiting artists is the artistic challenge, the publicity, and the opportunity to give back to the Gallery. At the time of writing, prices range from £25 to £7,000 for one of 50 Bridget Riley screenprints. Members receive 10% off all Limited Editions as well as advance notice of new Limited Editions being introduced – with some selling out very quickly. Gallery staff have identified regular Limited Edition collectors are considering how to further appeal to them. The Gallery expects to generate around £100,000 per year from the initiative. Other leading contemporary art galleries, such as the Serpentine and the ICA offer similar schemes, and interestingly the Whitechapel does not see them as competition. Rather, it has co-exhibited with the ICA at two international art fairs to date: this creates greater visibility than one venue working on its own, and allows crossover of customers. Art Plus events The Gallery has run annual Art Plus events for several years. These glamorous events have a different ‘plus’ each time: 2011 is Drama, 2010 was Music. The performers (and audience) usually include celebrities who have existing links to the Whitechapel or to the East London ‘scene’ – while also allowing the Gallery to reach people with a serious interest in other artforms besides contemporary visual arts. Tickets cost £145 and many sell to existing or potential Patrons and donors. Art Plus is effective at attracting corporate sponsorship, and includes an auction of donated artworks. In all, an Art Plus event can raise up to £100,000. Sue Evans, the Whitechapel’s Development Manager, advises that: “Whitechapel Gallery commits significant resources to producing such a high profile, high quality evening, bringing a dedicated team on board several months in 17 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial advance of the event. Art Plus is a unique event and concept, developed over time and relevant to Whitechapel Gallery’s remit, mission and audience.” Invitation to Art Plus Drama event Future plans The Whitechapel’s current fundraising focus is a £10 million endowment: Future Fund. This is an attractive means to create stability within the budget and to allow planning ahead with confidence. It would also increase the Gallery’s selfsufficiency at a time of public sector cuts. Future Fund originated with the capital fundraising campaign, which left the Gallery with an expanded and ‘battle hardened’ fundraising team and network of supporters. Future Fund aims to maintain momentum and offer existing and new supporters a further opportunity to support the Gallery ‘forever’. Happily, the campaign coincides with renewed interest in endowments within government and its agencies. In late 2010 Arts Council England awarded the Whitechapel £2.7 million towards Future Fund. Arts Council England sees the Gallery as a test case for how an arts organisation can run sustainably following a major expansion and how an endowment can help to maintain artistic excellence during operational and organisational changes. The Gallery is also keeping a close eye on the government’s new £80million matching fund for endowments, and hopes to benefit. The campaign will ‘go public’ in 2012 following in 2011 a period of research and targeting of corporate donations. The plan is to work with existing supporters before widening the net – the Gallery is particularly interested in building 18 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial relationships with technology firms arriving in East London as part of the government’s ‘Tech City’ initiative. The Gallery is keeping an open mind as to how it invests Future Fund – either going ‘solo’ or inputting to a joint fund. An Investment Committee composed of Trustees and staff, is being set up to oversee this. Success factors According to staff consulted, some of the general success factors underpinning income generation at the Gallery are: • Very hands-on involvement by Director Iwona Blazwick OBE in all income generation initiatives – she is felt to be key to the success of the expansion capital campaign and to the maintaining the Gallery’s international profile; • Mainstreaming income generation awareness and responsibility throughout all teams following the expansion project. In particular exhibition and education staff now generate ideas for income generation (which was not part of their roles before). The fortnightly team leader meetings are one forum to discuss these ideas; • Using Gallery Trustees and Patrons who have influence within specific networks; • A willingness to innovate, building on the Gallery’s credentials as the first public art gallery in the East End as well as the first major venue to show many artists who subsequently became household names. • Above all, a commitment to high artistic quality in all initiatives. Research sources • Interviews with Whitechapel Gallery staff: • Sue Evans, Development Manager • Rummana Naqvi, Senior Development Officer • Sophie Hayles, External Relations Officer • Jo Melvin, Senior Editions Officer • A guide to buying art, The Guardian, 13 October 2010; • Arts Council England invests Lottery funds in London to build arts resilience, Arts Council England press release, 15 December 2010; • Documents accessed via the Whitechapel Gallery website. All prices quoted are correct at the time of writing, but may change 19 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial 5 Project Hope at the Watts Gallery Innovation points • Ambitious organisational transformation plus £10 million building restoration to deliver sustainability for the next 100 years; • Focus on self-generated income via increased admission charges plus enhanced Friends scheme, retail and catering; • Use of unusual measures such as a collections review leading to deaccessioning of ‘non-core’ works, and an endowment. Context The Watts Gallery is an art gallery in the village of Compton in Surrey. It opened in 1904 to house the works of Victorian era painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts, and as such is one of the few galleries in the UK devoted to a single artist. Following contributions from his wife, his adopted daughter and other private donors, the collection has grown to over 6000 diverse objects including over 250 oil paintings, 800 drawings and watercolours, 130 prints, 200 sculptures, and 240 pieces of pottery as well as unique ephemera and memorabilia related to GF Watts, Mary Seton Watts and the history of the Gallery. By 2004, the anniversary of both Watts’ death and of the opening of the Gallery, the building was in a poor state of repair. A leaking roof and faulty sewage system were threatening the collection and making the gallery less appealing to visitors. The total visitor numbers at that time were approximately 11,000 which reflected the limited marketing of the Gallery and the infrequent new exhibitions. Shortly after the appointment of Perdita Hunt as the Gallery’s Director, the decision was taken to embark upon a major restoration of the Gallery to ensure its sustainability for another 100 years – Project Hope. The decision was taken because the Trustees strongly believed there was sufficient public demand to merit significantly raising the profile of Watts’ work and of the Gallery as the principal venue in which to view it. The delicate balance that such a major restoration had to achieve was highlighted by Maev Kennedy, Heritage Correspondent for the Guardian: “The challenge of Watts Gallery is to preserve its quality of mystery and wonder, while preventing the building from physically falling to bits. It is a precious place.” 20 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial Watts Gallery prior to restoration What happened and how One of Perdita Hunt’s first actions as Director was to restructure the board of Trustees to build its capacity to oversee Project Hope. Perdita states: “We needed to have only active Trustees: we couldn’t afford for people to be passive, so we recruited Trustees with the skills required to guide the project including project management, finance, fund raising and marketing.” Project planning started in 2005. The ambitious aims for the restoring the Gallery were tempered by the desire to return to the original vision of the gallery, which was ‘art for all’, and its original mission, which was to promote the work of G. F. Watts in the context of the 19th Century. It was also felt that previous management teams had aimed to achieve too much change too quickly. By contrast, Project Hope would represent an evolution, not a revolution. The following objectives were drawn up to guide Project Hope: • Marketing: raise awareness of the Gallery and its collection; • Conservation: save the building and collection; • Develop social history and arts education programmes; • Develop the Gallery’s audience and levels of income generated; • Develop the 4.5 acre estate; • Develop the organisation and make it fit for the next 100 years. The budget for Project Hope was set at £10.1 million. In 2006, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) granted a £4.3 million award to the project. This gave the project 21 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial credibility and was crucial to helping leverage further awards from other donors. In 2006 the Watts Gallery received a further boost: it was placed second in the final of the BBC TV series ‘Restoration Village’. This made a huge contribution towards raising the profile of the Gallery. Following the TV show visitor numbers increased significantly and the Gallery still receives visitors who learned of it first through the 2006 show. Perdita attributes the exposure to an intense focus on marketing and persistent “pestering of the BBC”. The restoration work began in February 2009. However, the contracted builder went bust shortly afterwards, costing the Gallery an extra £1 million in fees and causing significant delay while a new contractor was found. The Watts Gallery has now raised both the original £10.1 million required for the full restoration and, with further support from the HLF, has almost raised the additional £1 million needed to cover costs relating to the change in building contractor. Just £70,000 is still to be raised at the time of writing. The restoration work will complete in summer 2011, at which point the Gallery will re-open, having been closed throughout. The restored building will offer more attractive public spaces, greater access for those with disabilities, more space for the collection and better collection care controls. The existing retail and catering facilities will also be enhanced. Watts Gallery restoration works underway Future plans When the gallery closed for restoration in 2009, visitor numbers had already risen from 11,000 to 25,000, which represented the original target set at the beginning of Project Hope. The number of Friends of the Watts Gallery also rose from only 17 to approximately 15,000. 22 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial Despite these useful early increases in donors and visitors, the Watts Gallery is also introducing a number of further, major, steps to ensure its future economic sustainability. On-reopening in late spring, admission fees will increase from £3 to £7, with free access for Friends and cheap entrance every Tuesday. The charging of entrance fees is in keeping with the original vision for the Gallery as fees have been charged since 1904 when it first opened. Acting on professional advice, the Gallery’s legal structure has been changed to become a limited company registered for VAT. This enables VAT charged by contractors for the renovation of the building to be reclaimed. Lastly, the Watts Gallery announced in 2010 that it was de-accessioning two noncore works from the collection in order to raise a further £1.5 million for the Gallery’s endowment. The endowment is dedicated to the long term care of the collection. The Gallery is budgeting for an average of 3.5% interest per annum on the endowment, which will yield £150,000 per year in perpetuity for the conservation and restoration of art-works in the Gallery’s collection. The decision to sell items from the collection was not taken lightly. Working closely with the MLA and AMA, the Watts Gallery went into ‘listening mode’, seeking the views of trustees, volunteers, visitors and the local authority on the proposal. The collections committee audited the collection to identify the works least central to the core collection and therefore most appropriate for sale. Despite encountering pockets of resistance, the outcome of the consultation was agreement that the paintings, currently in storage, were suitable to be sold since this would ensure that the paintings would be seen, and would raise the funds required to care properly for the rest of the collection. The Gallery also sought legal advice, which confirmed that although the paintings were originally a bequest there was no legal obligation to keep them. Success factors According to Perdita, the Watts Gallery’s huge progress towards becoming economically sustainable is underpinned by: • An enduring and relevant founder’s vision; • Robust governance and committed Trustees; • The support of a lead patron right at the outset of the appeal; • The use of challenge funding to entice donors who feel that their money will go further; • Leadership and reinforcement of training, professional and personal development of the staff; 23 The document title: The document sub-title all set in 10pt Arial • Constant and powerful communication; • An army of volunteers; • A unique building and collection. Research sources • Interview with Perdita Hunt, Director of the Watts Gallery, and subsequent information received via e-mail; • 24 Documents accessed via the Watts Gallery website. Museums, Libraries & Archives Council T +44 (0)121 345 7300 F +44 (0)121 345 7303 Grosvenor House 14 Bennetts Hill Birmingham B2 5RS info@mla.gov.uk www.mla.gov.uk Leading strategically, we promote best practice in museums, libraries and archives, to inspire innovative, integrated and sustainable services for all. Third party logo ISBN 000-0-000000-00-0 © MLA 2010-03-03 Registered Charity No: 1079666