Jihohanácký kroj

advertisement

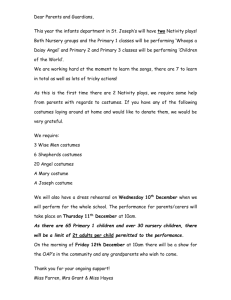

South Haná Folk CostumeJiří NovotnýA revived folk costume in our village. When, why and how? Folk culture is one of the pearls of Moravian identity, a unique feature which, regarding the degree of its preservation, variety and richness, doesn’t have many parallels in Europe. We didn’t want to lag behind, so we too brought our grist to the mill. :)1. IntroductionWhen in 2001 for the first time in roughly half a century a group of people from Manerov and two people from Bohdalice decided to hold a feast with folk costumes in Manerov, only optimists whose number would amount to one quarter of village inhabitants believed in the idea’s success. Others would shake their heads in disbelief, while the silent majority was silent, as majorities are. When everything was over, the pessimists disappeared, the silent majority became a minority and today, several years later after folk costumes have begun to be used in Bohdalice too, hardly anyone objects to the restoration of folk traditions.Only the greatest optimists believed from the beginning that one day it would be possible to take another important step forward and achieve the restoration of our own folk costumes from our region. Nevertheless, reality and the events of the past year surpassed their expectations. The folk costumes themselves became a reality, and a successfully accepted one. Now, in order to spread them further, it’s appropriate to learn more about them in the broader context as well.2. Expansion from southern regionsThe folk costume, which is the name for traditional, mainly festive folk apparel, gradually disappeared from wardrobes during the course of the 19th century. In some places this occurred earlier (in cities and wealthier areas), in other places later; men stopped wearing them earlier than women; the wealthy replaced them with ready-made clothing earlier than the poor. A change in the use of costumes dates back to the beginnings of ethnographic efforts to record the folk costume, to “save” it and also to use it in the ethnographic struggle. For practical reasons, ready-made clothing took over in everyday life (the price of fabrics, sewing, costliness of embroidery, but also washability – in this respect Baťa caused a sensation with his rubber boots). The folk costume continued to have a representative function, which is still the case today.In Moravian Wallachia, the Horňácký area, Kopanice and also in the Dolňácký and Podluží areas, the original sense of wearing folk costumes was replaced by the new, representative sense relatively continuously. The costume never dropped out of sight; it continued to develop, to improve. By contrast, in areas where costumes disappeared earlier (including our area) such continuous development was not possible. Also the communist regime played an important role by pulling strings for “the poor, the folk” in Wallachia and the so-called Slovácko area, while the prototype of a wealthy Haná native corresponded to the image of the “kulak”, who had no place in socialist society.Decades-long support of certain ethnographic regions and the marginalisation of Haná resulted in a significant change in the appreciation of these areas. In the 19th century almost all of Moravia proudly avowed Haná and people were ashamed of the designation “Wallach” or “Slovak”. They often said that “Wallachs are those drunken shepherds from the mountain, not us in the village”, while the term Slovak was originally used solely to refer to immigrants from Hungary. In the 20th century, however, Wallachia was extended to the foothills and Slovácko, as it had only started to be called at that time, was extended not only throughout the Kyjov area, but today it reaches almost to Brno and even the name Haná Slovácko was coined for the transitional area.A “general Moravian costume” started to be associated especially with the Kyjov folk costume (or the neighbouring Mistřín costume, but the names are often not used accurately and the composition of the costumes rented under this name is often a peculiar medley). Nowadays, it can be found far beyond the boundaries of its original purview. It is used in the Bučovice and Slavkov areas and has penetrated deep into the Vyškov area to the true Haná area, it is worn in the Brno area and even as far as western Moravia and the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands in the original Horácký area.The Mikulov area and its villages and houses occupied by settlers after the German expulsion saw the expansion of the Podluží costume, with its characteristic red trouser legs. Recently, this aggressive costume has even reached our area through clothes rental services, perhaps to demonstrate what it is capable of. From the south it has been pushing out the original costumes of the Kyjov area, just as the Kyjov costume occupied the area of the original south Haná costume.We can therefore observe in folkloristics a certain southern pressure which is historically demonstrable and can be traced in many a costume, including the Kyjov costume itself.3. Haná’s ReconquistaFortunately, however, there is an awareness of what belongs in which region, of what is tasteful and tolerable. More and more villages where folk costumes ceased to be worn long ago are returning to their use. More and more frequently, having undertaken such a costly enterprise, they are contemplating what to have sewn. A logical trend is to return to what is typical of each village and not to boast another region’s costume, even if it is prettified, when one can wear one’s own.There are even villages where Kyjov costumes were used for many years and civil war almost broke out when, after tenuous discussions, it was decided to return to the former Haná costumes. In this sense it is a warning for villages which are only starting to use folk costumes again not to become accustomed to imported costumes or fall in love with them. A habit easily becomes a vice and then it’s not so easy to stop, also because many prejudices persist such as “Haná skirts are too long”, “scarves are uncomfortable”, “costumes aren’t that nice” and the like. Such impressions, though mostly based on ignorance of the true nature of the Haná costume, are difficult to refute and present an obstacle in reconstructing and acquiring one’s own costume.The Reconquista was a movement by Spanish Christians to re-take previously held territories on the Iberian Peninsula occupied by the Moors. I used this term exuberantly to characterise the reconquest of the original Haná area by our folk costumes which are greatly outnumbered by “occupying” costumes from the south.4. How the research was conductedThe decision to reconstruct our region’s original folk costume and secure funding for the first set was easier than the reconstruction itself. I sought out various materials and drawings documenting the costume’s appearance, but the results were poor.For example, in the Vyškov museum they have several complete costumes, but these are from Švábenice or Vyškov, so it wasn’t possible to simply copy them for our purposes. The individual parts of the costume, for example the shirts, usually bore the “Vyškov” designation of origin or some other general name, which was insufficient for an unequivocal ascription of origin to our area.No drawings were found directly from our area. Although there are several collections of various gouaches, drawings, and later photographs from the area between Vyškov and Bučovice, as if by design none are from our precise region. For inspiration, albeit with great reserve, it was possible to look only at figures from different time periods and from regionally very distant villages in the surroundings, such as Němčany, Střílky or villages lying in the Vyškov Gate or on the northern slopes of the Litenčice Hills.In the end, we were able to determine with certainty only the basic colours, which correspond to the colours generally used throughout Haná, as is also confirmed by Moravian ethnography from the turn of the 20th century. The last men’s costume used was yellow and blue, a combination that predominated at the end of the 18th century, so it made no sense to “make up” an older reconstruction, i.e. a red-green combination that would correspond to much older costumes.5. Description of the parts of our costumeMen’s costume – classic yellow short pants, blue vest, white shirt, leather belt, high boots and a hat. It should be admitted that the design of the hat is the only element of the costume about which I speculated slightly. However, I believe the great variability and regional and temporal mutability of headwear justifies this speculation. Moravian ethnography ascribes a broad-brimmed hat to our area, which can be justifiably interpreted variously; in some villages a “small broad-brimmed hat” is more like what we would call a “bowler” and on the other hand the term could certainly also cover the Mexican sombrero. I did not consider it tasteful to adopt the flat “water spirit” hats from other regions of Haná, and so basically the modern design of the brim with curved edges on the sides won out, as it has been documented in other areas and might have been worn in our area as well, although sources do not mention it explicitly. The “modern” design of the hat is, I think, a sincere acknowledgement that our costume is the result of a 21st century reconstruction.Women’s costume – white blouse (sleeves), two petticoats and two aprons (all white – festive, the apron for common use has a colourful flower pattern). We use a cylinder structure (“jelito”) to support the skirt; alternately a half-shirt (“opléčko”) can be used. White stockings, low black shoes (the original shoes were colourfully decorated). A key, quite indispensable part of the costume is the large scarf called a “turečák” appropriately tied (which I am not able to describe here, as this is a secret skill of women). The bodice is red, which corresponds to many drawings from other areas and to the character of the costume, which was made primarily to be worn at feasts and for young girls, i.e. for gaiety and youth. If we were to reconstruct clothing for older generations I would consider black (or possibly other dark colours) to be suitable. The decorative elements of the costume were more or less determined by our available finances. Since there was no money left for ornaments or accessories, the traditional “barley twist” pattern of black embroidery can be found only on the shoulders of the women’s blouses and there is also yellow embroidery on the edge of the apron (a possible, but expensive accessory for the women’s costume is an embroidered halfshirt). Lace decorates the large collar and sleeves. Other decorations are ribbons sewn onto the bodice, a ribbon in the lower hem of the bodice and a ribbon on the men’s hat. The decoration of the men’s belt is very simple. Thin red ribbons are used at the neck and on the back side of the pants and tassels hang from the buttons to the boots.Initial concerns that such a sparingly decorated costume would not be nice were, in my opinion, completely dispelled in practice. Prettified and over-decorated folk costumes from southern areas seem to suppress details and obscure the overall impression. By contrast, the costume from south Haná, as we have reconstructed it, is elegant in its simplicity, candour and something which I would call “trueness”. It doesn’t pretend to be something it’s not.For that matter, the sparse embroidery and lace corresponds to the period which we tried to imitate in our reconstruction. Regular people in the first half of the 19th century didn’t have their costumes covered with embroideries either, and lace did not trail after them on the ground wherever they went. The pretentiousness of certain costumes which developed continuously from the 19th century and through the entire 20th century is today in my opinion even pathological, not genuine and the ancestors of the young men from the Podluží or Kyjov areas would probably be unable to recognise their descendants in all cases.Moreover, we’re at the birth of new costumes, so it’s possible to improve them over time, which has always been a long-term, unending process. Slight improvements may arise from the renewal of the art of embroidery in our area or simply from the fact that there will be more people willing to buy their own costume and invest more money in its decoration. However, it is important to preserve a sensible level of taste and genuineness, so that costumes are not cluttered or spoiled with too many inappropriate patterns or accessories.Common use also necessitates less festive aprons. In view of the various occasions throughout the year when the costume can be worn, not only during the feast in August, there is also a need to reconstruct men’s and women’s coats. And interest among men with growing, it will be necessary to procure typical cloaks as well.6. What costume, whose?While I was occupied with searching for ethnographic materials, writing a grant request and subsequently with the process of creating costumes, I did not give any importance, perhaps erroneously, to the question of what the costume should be called. Not that I forgot about it, as even in applications for support from various institutions it was necessary to fill in the name, so I used the working title “South Haná costume”.However, certain people considered this issue important and in the meantime brought their own ideas forward, so that they too could make history. Recently one could also hear proposals to name the costume after certain villages, be it “Manerov”, where it was used for the first time, or “Bohdalice” after the name of the local administrative capital (that would, however, be incorrect anyway, since the name of the village is Bohdalice-Pavlovice, and that would simply be too much). Debates among advocates of these proposals even developed into quarrels. And despite the fact that folk costumes are justifiably an emotional matter, there were too many emotions in the end.Let’s take a look at the names of folk costumes in the rest of Moravia. The main types are simply named after ethnographic regions, e.g. “Haná”, “Wallachia”, etc., or after the names of smaller parts of these regions (e.g. Blaťácko). In regions where long uninterrupted development has led to differentiation among neighbouring villages the costumes are named after the villages. The only exception to this rule is the Kyjov costume, which is so called despite the fact that the same or very similar costumes were worn in several neighbouring villages (moreover, the terms “lower Kyjov” and “upper Kyjov” costumes are used with the relevant villages referring to their own costume, even though others call it the “Kyjov” costume, so the Kyjov exception actually proves the rule).In the light of the above-mentioned facts, is it correct to indulge the ego and name our costume after one village? There does exist one argument for Bohdalice. Already in the 19th century this village was quite unique in that it was a bright spot of Slavic revival in the otherwise quite dilatory territory of most of Moravia. While for example nearby Vyškov was under heavy German influence, Bohdalice cherished patriots and represented a sort of beacon, a leading element. Therefore, naming something which is at present common to the whole area after Bohdalice could be considered the continuation of an excellent tradition, not an excess.On the other hand, there is the unmistakable fact that the costume in the whole area between Vyškov and Bučovice (except for the German linguistic island where there were several specific elements) was practically identical. When I sometimes hear considerations about whether it would be possible to use certain differentiating elements in costume collections for other villages, I have to say that these ideas are based only on the desire to be different and not on any substantiated assumption that in the past there existed visible dissimilarities among individual villages in the region.If our wish is for Haná’s Reconquista to continue and for our folk costume to return to other villages as well, then naming it after Bohdalice or Manerov would be a mistake. A common characteristic of the broader surroundings, such as landscape, history and the current state of affairs, brings me to the view that the working title “South Haná” should become the costume’s official name. That way no one can object, and it is unlikely that anyone will mistake it for another costume.7. Supporting the costume’s use and identityVillage life and the environment represent the most important priorities which we are following in our village in the current election period. For a certain level of agreement and comfort in the village (villages) we certainly need many preconditions. Our own folk costume with a singular character based on local tradition is, in my opinion, a unique external source of identity and identification of inhabitants with their village. And by “village” I do not mean a group of houses, a cadastral area or an office, but rather a community of people.In this sense it is unequivocally in the interest of the village (and here I again refer to the village as an institution) to support on the one hand the expansion of the collection of folk costumes owned by the village which are to be lent out for municipal events and to associations in the village for their events, and on the other hand private acquisitions of folk costumes, which is the third and crowning step culture. in the renewal of this segment of folk