Expected Dividend Growth, Valuation Ratios and Rational

advertisement

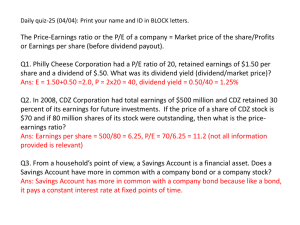

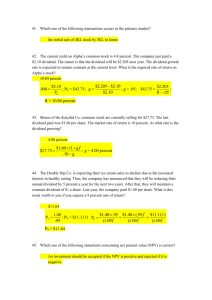

1 Expected Dividend Growth, Valuation Ratios and Rational Optimism Gary Santoni Department of Economics Ball State University Muncie, IN, 47306 Email: gsantoni@gw.bsu.edu Alex Tabarrok George Mason University Tabarrok@gmu.edu Published as: Santoni, G. and A. Tabarrok. 2002. Expected Dividend Growth, Valuation Ratios and Rational Optimism. Journal of Financial and Economic Practice 1 (1): 110119. 2 Stock market valuation ratios reached historically unprecedented levels in the late 1990s and continue to be very high today.1 Chart 1 shows the behavior of the price earnings ratio for stocks contained in the Standard and Poor’s Index. The data, which are updated from Shiller (1996), are annual for the years 1871-2000. As indicated, the P/E ratio of 28 recorded in 2000 had never before been attained in the previous 130 years. The data in Chart 2 show that the recent behavior of the dividend price ratio relative to its historical norm is even more stark. As of this writing (late 2001), stock prices have fallen, especially in the once high-flying Internet sector. The various ratios have fallen to more "reasonable" levels but are still high relative to historical averages. While prices have fallen so have dividends and earnings and the issue raised in the literature concerns the ratio of prices to various measures of the fundamentals. As Chart 3 shows, these ratios are independent of the level of prices. The dividend price ratio, for example, (which in late 2001 stands at 0.017), is still below its 1996 level of 0.024 when Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan characterized market participants as “irrational,” and well below its historical average of 0.048. In addition, it is also clear from Charts 1 and 2 that there are times other than the late 1990s (for example, 1893-96, 1930-34, 1960-72, and 1991-93) when the P/E ratio was unusually high and the dividend price ratio unusually low.2 This paper uses the Gordon growth model to explain variation in these valuation ratios. In particular, the model is used to show that acceleration in the expected dividend growth rate beginning in the late 1950's is consistent with the behavior of the price earnings and dividend price ratios since that time. This explanation of the behavior of the ratios provides a more optimistic outlook for the future behavior of stock prices than, for example, Campbell and Shiller (1998) who suggest that the recent levels of “...these ratios are extraordinarily bearish for the 3 U.S. stock market (p. 24)” or Fama and French (2000) who argue that, “...the low end-of-sample dividend yield implies low expected (future) stock returns (p.15).”3 The Gordon Growth Model and Valuation Ratios We use Gordon’s (1962) growth model to assess the behavior of the price earnings and dividend price ratios. This model says that the current price of a stock, Pt , depends on three factors: 1) the dividend the stock paid in the previous period, Dt 1 , the current period expectation of the future growth rate in dividends, g t , and the current period discount rate relevant for stocks in the firm’s risk category, rt , as related in equation (1). Pt Dt 1 ( 1 gt ) rt g t (1) Notice that equation (1) can be rearranged to obtain an expression for the dividend price ratio as in equation (2). Dt 1 rt g t Pt 1 gt (2) Furthermore, if both sides of equation (1) are divided by trailing earnings, Et 1 , as in equation (3), an expression for the price earnings ratio is obtained. Pt D 1 gt t 1 ( ) Et 1 Et 1 rt g t (3) Equations (2) and (3) are useful. They indicate that both valuation ratios are driven by the discount rate, rt , and the expected growth rate in dividends, g t . In particular, an increase in the discount rate increases the dividend-price ratio while an increase in the expected growth rate in dividends lowers it. These changes operate in reverse on the price-earnings ratio. In addition, 4 the price-earnings ratio increases with an increase in the proportion of earnings paid out in dividends, Dt 1 / Et 1 . The dividend price and price earnings ratios are both very sensitive to changes in the expected growth rate in dividends and discount rate. For example, consider the dividend price ratio given by equation (2). The mean of this ratio is 0.048 over the 1871-2000 interval. Since g t is small, typically around 2 percent (see further below), this implies that the mean difference between rt and g t is about 0.05. Suppose the mean of g were one percentage point higher with the mean of r unchanged. In this case, the dividend price ratio would fall from about 0.048 to about 0.038 – almost a 25 percent reduction. A similar result holds for the price earnings ratio. If the mean difference between rt and g t is about 0.05, the term inside the parentheses in equation (3) is about 20. Since the average payout ratio, Dt 1 / Et 1 , is about 0.65, equation (3) implies an average price earnings ratio of 13. This is close to the actual average of 13.9. Again, a one percentage point increase in the mean of g results in an increase in the price earnings ratio from about 13 to 16.25 – an increase of 25 percent. The large swings in the dividend price and price earnings ratios shown in Charts 1 and 2 can therefore be explained by relatively mild variation in the expected growth rate of dividends.4 Some Potential Explanations of Current Levels of the Valuation Ratios The most common explanation for high valuation ratios is that these are signs of an unsustainable price bubble brought about by irrational exuberance. Shiller (1989, 2000) and Campbell and Shiller (1998, 1988) are proponents of this explanation. A few economists, 5 however, have tried to explain recent valuation ratios on the basis of a permanent fall in the discount rate – a fundamental factor. For example, Fama and French (2000) argue, in the context of the Gordon model, that a decline in the discount rate, rt , explains the appreciation in stock prices in recent years as well as higher price earnings and lower dividend price ratios.5 Siegel (1999) presents a similar argument and suggests that the high current level of stock prices relative to the fundamentals imply, “Either 1) future stock returns (discount rates) are going to be lower than historical averages, or 2) earnings (and hence other fundamentals such as dividends or book value) are going to rise at a more rapid rate in the future (p.14).” Like Fama and French, Siegel (1999, p. 15) concludes that the bulk of the explanation for the recent behavior of the valuation ratios shown in Charts 1 and 2 is a decline in the discount rate. However, Siegel indicates that this cannot be the whole story because relying solely on this explanation requires a discount rate below the current yield on inflation-protected government bonds. Since these bonds are safer than equities, their expected returns should be lower not higher than expected equity returns. As a result, Siegel suggests that part of the explanation “must be due to the expectation that future earnings (and dividend) growth will be significantly above the historical average (p. 14).” A similar suggestion is made in Carlson (2001, p. 3), Carlson and Pelz (2001, p. 2) and Balke and Wohar (2001). We pursue this alternative explanation. Of course, expectations regarding future growth in earnings and dividends are not directly observable but we provide a new method for “backing out” these expectations from Gordon’s model. Using the model, we ask what investors would have had to expect about dividend growth rates to generate the price series that actually occurred. These derived expectations can then be compared to the actual series of dividend growth to see whether the 6 derived series is plausibly rational (Is the derived series consistent with actual dividend growth?).6 Doing this necessarily requires us to drop the assumption used in constructing the Gordon model that the dividend growth rate has a mean that is constant over time. Instead, we follow Barsky and DeLong (1993, p. 293) who “...see investors as having to estimate period by period a growth rate that is nonstationary.”7 The conflict between this assumption and the model is why we regard our procedure as a back-of-the-envelope calculation. We use the Gordon model despite this problem because it produces a startling result – the sharp swings in the price earnings and dividend price ratios shown in Charts 1 and 2 are consistent with a simple model based solely on fundamentals so long as that model allows for changes in the expected growth rate of dividends.8 Expected Growth in Real Dividends Chart 4 plots the expected annual growth rate in real dividends that we derive from the model. To obtain the series, we solve equation (1) for g t . Our calculations use the actual values observed for Pi and Dt 1 . In addition, we assume that the real discount rate for stocks, rt , is constant and equal to 8.0 percent over the entire period. The expected growth rate in dividends implied by the Gordon model oscillated around a mean value of 2.6 percent with a standard deviation of 1.4 percentage points prior to 1956. Since then the growth rate accelerated sharply rising to a mean level of 4.3 percent. The standard deviation in the later period is 1.1 percentage points. Because we have worked backwards by solving the model for the expected growth rate in dividends implied by the actual time series of stock prices and our assumption regarding the discount rate, it is very important to ask whether 7 the solution for g implied by the model is plausibly rational. Is the series that we derive from the model a reasonable representation of the expected value of the realized (observed) series? Chart 5 plots the expected growth rate in real dividends (shown in Chart 4) against the realized annual growth rate. The realized growth rate is clearly much more volatile (standard deviation = 0.13) than the expected growth rate (standard deviation = 0.015) as is typical of realized versus expected values. Furthermore, the means of the two series do not differ from one another in a statistical sense. The average annual difference between the realized and expected growth rates is 0.015 which is statistically indistinguishable from zero (t-score=1.41). In addition, the time series of the differences between the realized and expected growth rates is white noise as expected if the growth rate derived from the Gordon model is the expected value of the realized rate. 9 It is important to note that the data fails to reject the model even though we allow for only one degree of freedom – changes in the expected dividend growth rate. Of course, if we were to allow for variation in the discount rate, the same conclusion would hold a fortiori. We are not so much arguing for a pure dividend growth explanation as saying that such an explanation is not inconsistent with the data. The above suggests that the expected growth rate in real dividends is arguably rational. This together with the sensitivity of the dividend price and price earnings ratios to variation in the expected growth in dividends implies that increases in expected dividend growth can account for the current levels of the ratios. For example, expected dividend growth averaged 0.066 in the last three years of the data. This, together with equation (2) and our assumption of an 8.0 percent discount rate implies a dividend price ratio of 0.013. The average of the realized series over the same period is 0.014. 8 The rationality of the expected dividend growth rate can also be seen in the context of changes in the macro-economy. Chart 4 suggests that with the exception of a break in the 1970s the expected growth in real dividends has been on a long upward trend since about 1950. Consistent with this, output volatility has been on a long-downward trend since the 1950s, again with the exception of a break in the 1970s. Blanchard and Simon (2001), for example, estimate that quarterly output volatility has declined theefold since the early 1950s, from about 1.5% to less than 0.5% currently. As a result, output expansions have become considerably longer over time and recessions have become shorter. It is exactly these sorts of changes that should be reflected in expectations of real dividend growth, as indeed appears to be the case. Conclusion Large changes in valuation ratios can be explained by relatively small changes in the expected dividend growth rate. We use the Gordon growth model to back out an "expected" dividend growth rate and we compare this rate with the actual rate of dividend growth. We cannot reject the hypothesis that our estimated rate is a rational expectation of the actual. As a result, a model of valuation ratios based solely on a handful of fundamentals can easily explain the variation in the data. In particular, the historically high ratios of the late 1990s and today are consistent with rational expectations about dividend growth. Such expectations, moreover, appear reasonable in the context of slowly accumlating, long-term changes in the economy that are reducing output volatility, increasing the duration of expansions and reducing the duration of recessions. Contrary to a number of recent analyses, optimism about the future is not ruled out by the data. 9 Bibliography Balke, Nathan S. and Mark E. Wohar. “Explaining Stock Price Movements: Is there a case for Fundamentals.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Review, (Third Quarter, 2001), pp. 2234. Barsky, Robert and J. Bradford DeLong. “Why Does the Stock Markets Fluctuate?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, (May, 1993), pp. 291-311. Blanchard, Oliver and John A. Simon. "The Long and Large Decline in US Output Volatility." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (2001:1). Blanchard, Oliver and Mark Watson. “Bubbles, Rational Expectations and Financial Markets.” In Paul Wachtel, ed., Crises in Economic and Financial Structure, (Lexington Books 1982), pp. 295-315. Campbell, John and Robert Shilller. “Cointegration and Tests of Present Value Models.” Journal of Political Economy, (October 1987), pp. 1062-88. __________. “Stock Prices, Earnings, and Expected Dividends.” Journal of Finance. (July 1988), pp. 661-76. __________. “Valuation Ratios and the Long-Run Stock Market Outlook.” Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 28, No. 2, (Winter 1998), pp. 11-26. Carlson, John B. and Edward A. Pelz, “A Retrospective on the Stock Market in 2000,” Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, (January 15, 2001), pp. 1-4. Carlson, John B. “Why is the Dividend Yield So Low?” Economic Commentary, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, (April 2001), pp. 1-4. Diba, Behzad and Herschel Grossman. “Rational Bubbles in Stock Prices?” (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 1979, 1985). Donaldson, R. Glen and Mark Kamstra. “A New Dividend Forecasting Procedure that Rejects Bubbles in Asset Prices: The Case of 1929's Stock Crash.” The Review of Financial Studies (Summer, 1996), pp. 333-383. Fama, Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French. “Disappearing Dividends: Changing Firm Characteristics or Lower Propensity to Pay?” Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 60, No. 1 (April 2001), pp. 3-43. __________. “The Equity Premium,” The Center for Research in Security Prices, Working Paper 522, (July 2000), pp. 1-34. 10 Flood, Robert and Peter Garber. “Market Fundamentals Versus Price-Level Bubbles: First Tests.” Journal of Political Economy (August 1980), pp.745-70. __________. Bubbles, Runs and Gold Monetization.” In Paul Wachtel, ed., Crises in Economic and Financial Structure (Lexington Books, 1982), pp. 275-93. Flood, Robert P., Robert J. Hodrick and Paul Kaplan. “An Evaluation of Recent Evidence on Stock Market Bubbles.” NBER Working Paper No. 1971, 1986. Galbraith, John Kenneth. The Great Crash, (Hughton Mifflin, 1955). Gordon, M. 1962. The Investment, Financing and Valuation of the Corporation. Irwin, Homewood, IL. Keynes, John Maynard. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1935). Kindelberger, Charles P. Manias, Panics, and Crashes. (Basic Books, 1978). Macaulay, Frederick. Some Theoretical Problems Suggested by the Movements of Interest Rates, Bond Yields and Stock Prices in the United States Since 1856, (NBER, 1938), pp. A1-12-161. Rappoport, Peter and Eugene White. “Was There a Bubble in the 1929 Stock Market?” Journal of Economic History, (September 1993), pp. 549-74. __________. “Was the Crash of 1929 Expected?” American Economic Review, (March 1994), pp.271-281. Shiller, Robert. “Price Earnings Ratios as Forecasters of Returns: The Stock Market Outlook in 1996.” Posted July 21, 1996 at http://www.econ.yale.edu/shiller/pratio.html. __________. Irrational Exuberance. (Princeton University Press, 2000). __________. Market Volatility. (MIT Press, 1989). __________. “Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends?” The American Economic Review, (June, 1981), pp. 421-36. Siegel, Jeremy J. “The Shining Equity Premium,” Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 26, No.1, (Fall 1999), pp. 10-17. Stiglitz, Joseph. “Symposium on Bubbles.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, (Spring 1990), pp. 13-18. 11 West, Kenneth. “Dividend Innovations and Stock Price Volatility.” Discussion Paper #113 (Princeton University Working Paper, July 1986). White, Eugene W., ed. Crashes and Panics: The Lessons from History. (Dow Jones/Irwin, 1990). 12 Endnotes 13 14 15 16 17 1. Papers discussing valuation ratios include Balke and Wohar (2001), Campbell and Shiller (1998), Siegel (1999), Carlson (2001), Carlson and Pelz (2001), Fama and French (2000) and Shiller (1996). 2.Of course, prices can be unusually high or low relative to measures of the fundamentals. The papers referenced above are more concerned with episodes when prices are high relative to the fundamentals. 3.See Siegel (1999), pp. 10 and 15 for a similar argument. 4.See also Barsky and DeLong (1990, p. 269). 5.See Fama and French (2000) who conclude that, “The unexpected capital gains for 1950-1999 are largely due to a decline in the discount rate (p. 15).” 6.Using a much more complicated procedure, Donaldson and Kamstra (1996) and Barsky and DeLong (1993) derive series for the expected growth rate in dividends. Both series cover periods shorter than the period examined here and neither includes the more recent period during which the valuation ratios shown in Charts 1 and 2 reached their record levels. 7.A nonstationary growth rate is one for which the mean varies over time. Dropping this assumption is problematic since derivation of the Gordon Model makes use of it. (See Kamstra and Donaldson 1996, p. 345). 8.We use the model in the same spirit as Fama and French (2000) who argue that their “... conclusion does not rest on the validity of the Gordon Model. All valuation models say the dividend yield is driven by expected future returns (discount rates) and expectations about future dividends (p. 15).” 9.Our hypothesis is that the realized growth rate in real dividends, Gt , represents a single draw from a distribution of possible outcomes at time t . The mean of the distribution is the expected growth rate in real dividends, g t , that we derive from Gordon’s Model. Hence, Gt will differ from g t by a white noise error, E t , as in the following equation. Gt g t Et The autocorrelations and partial autocorrelations of E t at all lags through 36 are statistically indistinguishable from zero and the Ljung-Box Q statistic at 36 lags is 44.7. Hence, the test fails to reject the null that E t is white noise.