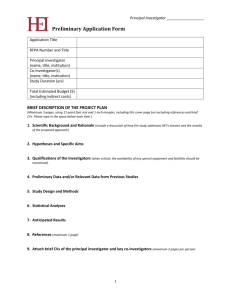

Identifying and Addressing Individual Conflicts of Interest in Research

advertisement

IDENTIFYING AND ADDRESSING INDIVIDUAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST IN RESEARCH June 27-30, 2010 Robert R. Terrell University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Analyzing Financial Conflicts of Interest in Research Much of the ongoing discussion about financial conflicts of interest in research centers on what external financial interests investigators should be required to report to their institutions, and what policies and procedures institutions should implement to assess such financial interests for potential conflict, and then manage and report on such conflicts. Less attention has been paid to the factors or considerations that an institutional official or committee should employ in assessing whether a disclosed financial interest creates a conflict, the nature and seriousness of a conflict, and whether it should and can be eliminated or effectively managed. This paper is a working effort to identify a set of parameters or dimensions that should be considered in the conflicts assessment process. By considering these parameters a conflicts review committee may be able to more effectively and consistently distinguish situations that create a higher risk for potential bias, and may be able to craft management plans tailored to the specific roles and interests at stake. The harm that the entire conflicts of interest assessment process is intended to reduce is the introduction of avoidable bias, broadly understood, into the research process. The premise is that an investigator who has a personal financial interest related to the research may be less objective in designing, conducting or reporting on the research than she or he would be in the absence of the personal financial interest. Stated another way, a personal financial interest related to the research creates an incentive that can conflict with the investigator’s primary responsibility to exercise independent professional judgment on matters relating to the research. In considering the appropriate components of a process designed to reduce bias arising from financial concerns, one fundamental concept is worth keeping in mind. A conflict of interest arises because of competing interests, not because of the ultimate actions taken in the context of the competing interests. That is, a conflict of interest exists where a secondary interest, here a personal financial interest, provides an incentive for an investigator to make a judgment or determination about a primary interest or duty, here the conduct of objective research, that differs from the judgment that would be made in the absence of the secondary interest.1 The conflict of 1 The judgments of concern are not limited to conscious or intentional decisions. It is increasingly recognized that financial incentives can alter behavior at the subconscious level. See the research discussed in AAMC: The Scientific Basis of Influence and Reciprocity: A Symposium (June 12, 2007). Therefore, the conflicts of interest assessment The National Association of College and University Attorneys 1 interest exists whether or not the financial interest actually causes the investigator to make any different judgment. Whether and to what extent a specific individual’s judgment or decisions may be affected by a competing interest depends both on the objective nature and extent of the interest, and on subjective factors that vary across individuals – awareness of the potential for bias, wealth effects, relative importance of financial and non-financial rewards. In light of these considerations, the conflicts of interest assessment and management endeavor is necessarily (and unavoidably) concerned with reducing the potential for biased judgments in the conduct of research. It is a probabilistic exercise and, as such, in any individual case there is a risk of over or under regulation. At any given point on the management spectrum there is a risk that unnecessary conditions are being placed on the researcher so that the costs of such management (in administration, delay or inhibition of important research) outweigh the value of the reduction in the adverse consequences of bias. But there is also the risk that the conditions will be inadequate to reduce the incidence and adverse consequences of bias to an acceptable level. The difficulty is identifying relevant factors that will help the committee find the right, or at least a reasonable, point on the spectrum. The Task of the Conflicts Review Committee In broad terms, the task before a conflicts review committee is to determine whether an investigator’s financial interests create an appreciable risk of bias in the investigator’s decisions relating to the research, the magnitude of the risk, the consequences of potential bias, the available options for eliminating or reducing the conflict, and the relative costs and benefits of the options. Assessing Whether There Is a Conflict of Interest Existing and proposed conflict assessment procedures start from the assumption that the institutional review committee will have access to information about all of the investigator’s significant financial interests related to the research and a complete description of the proposed research and the investigator’s role in it. Obviously, this information is necessary in order for the committee to determine whether the research may affect the value of the financial interest, or the financial interest may affect the research, and the potential for decisions of the investigator to influence outcomes that affect value of the financial interest. But how, exactly, is the committee to go about this evaluation? One approach is for the committee to try to evaluate what might be called the “bias incentive” created by the arrangement, that is, the prospect for reward tied to the results of the research, and then determine whether the investigator is in a position to make decisions which, if biased, would significantly affect the research. If the financial interest creates a bias incentive and the investigator has a role that would permit him to act on such bias, then the investigator has a financial conflict of interest. process is not concerned solely, or even primarily, with those competing interests that create an obvious incentive to make intentional decisions that are inconsistent with primary professional responsibility. The National Association of College and University Attorneys 2 Bias Incentive In a simple case, assume the results of research may directly affect the value of the investigator’s financial interest. For example, consider an investigator who has a stock interest in a start-up company that has rights to a technology that the investigator proposes to evaluate in his laboratory. Assume that preliminary positive research results will increase the value of the stock, and that if a product ultimately comes to market the value will be even greater. In this situation the bias incentive might be defined as: Bias Incentive = V x P x D Where V = the amount or value of the potential increase in the financial interest as a result of positive research results P = the probability of the increase given such positive results D = the discount factor for the time until the value may be realized In this model, the size of the bias incentive is related to the size of the reward, adjusted by the probability of its occurrence and the projected time until its occurrence. While obviously it would be difficult to apply the formula quantitatively, it qualitatively captures the concept that high value, high probability, near term effects of the research create a greater potential for bias than lower value, lower probability, more remote effects.2 In addition to providing at least a qualitative basis for evaluating the potential for bias, this framework suggests ways in which it can be reduced or managed. If the magnitude of the risk of bias is a function of the size of the potential reward, its probability, and when it will occur, then reducing either the size or probability, or extending the time until it can be realized, may each be a viable way of reducing the bias incentive to acceptable levels. Value. This framework assumes that what is most important is not the absolute value of the existing interest, but the potential of the research to affect the value of that interest.3 So, while $10,000 in reported consulting income and a $10,000 stock interest are equal in value, if the consulting income is a fixed amount that will be unaffected by the results of the research but the stock interest will be affected by the results, then the bias incentive associated with the consulting interest is lower.4 Probability. While in some cases there may be a direct one-to-one correspondence between the results of the research and the impact on the investigator’s financial interest, in other 2 The hypothesis here is that the risk of actual bias is directly related to the size, probability and temporal proximity of the potential financial reward. Perhaps this is not true. It does, however, seem plausible and is in keeping with the commonly accepted notion that people are more motivated by large, relatively certain, and near term rewards than they are by smaller, less likely rewards in the future. 3 This is not to say that an existing interest that will not vary with the research results cannot be a source of bias. See discussion of “reciprocity”, infra. 4 One implication is that some small interests, perhaps even below applicable reporting thresholds, may create a larger bias incentive than other significantly larger interests. The National Association of College and University Attorneys 3 cases the research in which the investigator is involved may be just one step in a long chain of events that must occur before the value is realized. Thus, for example, if an investigator is the inventor of a technology that it is hoped may ultimately lead to the development of an FDAapproved product, and the investigator would have a royalty interest in sales of any such product, there is a significant probability that no income will ever be realized even if the results of the investigator’s proposed pre-clinical studies are positive. Time Discount. If the payoff, or the ability to realize the payoff, is far in the future, then it may be reasonable to assume that the bias incentive is significantly less than it would be if the same reward were expected tomorrow. Distant rewards, even if not otherwise speculative, may have less impact on current behavior than lesser near-term benefits. In assessing these factors it is worth noting that the bias incentive is not a function of the actual value prospect, probability and time horizon, but of the investigator’s subjective belief about these factors. That is, an investigator who wildly overestimates the prospective reward and/or probability of occurrence and underestimates the time to realization has a larger bias incentive than if he or she accurately assessed the situation. Conversely, one who is more pessimistic may have a lower bias incentive. Institutions should probably apply a “reasonable person” standard in assessing the magnitude of risk for bias: what would a reasonable person believe about the prospects for gain? If, however, the institution has reason to know that the investigator appears to be inordinately bullish or optimistic about the prospect for positive results, then it may determine that the risk for bias is higher and calls for more stringent management or oversight. What of situations where the relationship between the outcome of the research and the investigator’s financial interest is not direct? For example, assume an investigator has an ongoing consulting relationship with the manufacturer of an FDA-approved drug under which he is paid a fixed amount per day, and the investigator proposes to be involved in a study of the comparative effectiveness of several drugs approved for the same indication. In such situations there are at least two different influences at play that might create a risk of bias: (1) the investigator’s interest in the continuation of the consulting relationship; and (2) a sense of indebtedness or “reciprocity” arising from the company’s past payments to the investigator. Here, the research may directly affect the financial interest of the company for which the investigator consults, but the potential impact on the investigator’s financial interest is less direct. The strength of the bias incentive is further clouded because more variables are involved than where the financial impact is direct. Would adverse findings lead the company to terminate the consulting arrangement? How important is the consulting relationship to each party? How long does the investigator expect or hope it will continue? Is the investigator compensated at a fair market value rate for services, or at a rate that is “generous”? What does the investigator believe about these factors? All of these things affect how much bias incentive the relationship may create, but can be extremely difficult for a conflicts review committee to assess. While there are uncertainties about the extent to which these situations give rise to a bias incentive (in part due to uncertainty about the company’s motives and interests in the relationship, and lack of clarity about what the investigator’s beliefs and expectations are), certain principles seem sensible. First, the larger past payments have been, the more likely it is The National Association of College and University Attorneys 4 that the investigator will want them to continue. Second, the more generous the payments have been (that is, if they appear to be significantly disproportionate to the services actually rendered), the greater the interest in having them continue, and the greater the sense of reciprocity on the part of the recipient. While some have argued that fixed payments unrelated to the research in question are unlikely to bias investigators, the general public certainly believes that generous payments at minimum help establish a sort of loyalty that may interfere with objective judgment, or, worse, that they have the purpose and effect of buying scientific support for the payer’s products. Investigator’s Ability to Affect the Research After the review committee has assessed the bias incentive, it needs to determine if the investigator has any ability to influence outcomes that will affect his or her financial interest or the interest of a party that has provided the investigator with a benefit. An investigator may have a large bias incentive, but if he or she has no role where the bias could affect some decision or judgment in a way that would influence the research, then there is no conflict of interest. For example, if the only role of a clinical investigator with a significant financial interest in the outcome of a double-blind placebo controlled trial is to make standard clinical assessments of subjects others have enrolled, and the investigator is effectively blinded to treatment category, then her financial interests do not seem capable of biasing the research.5 If, however, the investigator has both a bias incentive and an ability to act on that bias in a way that could “directly and significantly affect the design, conduct, or reporting” of the research,6 he or she has a financial conflict of interest. In assessing whether an investigator has the capacity to make biased decisions or judgments that affect the research, the review committee must look carefully at the investigator’s roles where bias might come into play. What role does the investigator play in the design of the research? Does the investigator recruit or consent subjects? Does the investigator carry out experiments and collect data? Are results objective, or is there some subjectivity in characterizing results? What role does she have in analyzing the data? If the investigator is involved in analysis, is she blinded to the experimental conditions? Is the investigator involved in deciding how and when results will be presented? Is the investigator solely responsible for any of these roles, or are other, non-conflicted individuals involved? Consideration of these questions can help a review committee determine how an investigator’s possible bias might affect the research, and may point to strategies to reduce or eliminate the potential for bias. 5 Even a subconscious bias in favor of a particular outcome cannot have a systematic impact where the investigator has no way of knowing to which group a particular subject belongs. The key is that the investigator be truly blinded. In some situations investigators may have strong suspicions about which subjects are in a treatment category because of side effects or knowledge of test results that correlate with use of the study compound. 6 42 CFR 50.605(a)(1). The regulation applies the quoted language to the evaluation of a “significant financial interest”. In the model proposed in this paper the emphasis is on assessing the risk of bias created by the financial interest and the ability to act on such bias. It would seem that the “directly and significantly affect” analysis would allow for consideration of the factors described here: the size, likelihood and time to realization of the financial effect, and the investigator’s ability to make decisions that affect the research. The National Association of College and University Attorneys 5 The Risk-Benefit Analysis One recent discussion of conflict of interest management processes states that once a conflict has been determined to exist, the task of the committee is to evaluate the risks of potential bias and weigh them against the benefits of allowing the research to go forward.7 If the benefits outweigh the risks, or outweigh them substantially, the research can proceed. If the risks outweigh the benefits, then the investigator cannot participate, unless a management plan can be devised that brings the risks substantially below the benefits. While this approach seems reasonable in principle, it is not at all clear that it can be applied practically. How is this sort of risk-benefit analysis to be accomplished? In many situations the magnitude of the risk of biased decision-making is little more than a guess (and depends on assumptions or speculation about how a financial incentive may affect a specific investigator’s decisionmaking). And the nature and magnitude of the harm that may result from actual bias may be equally unclear. The benefits side of the equation is subject to similar uncertainty: how likely is the research to answer the scientific question posed? How important is the answer? Furthermore, how are intangible risks, such as risks to data integrity or of delays in dissemination of results, to be compared or balanced against potential benefits such as resolution of important scientific questions or speedier development of useful treatments or other products? To recognize that the risk-benefit assessment does not at this point lend itself to a quantitative solution is not to say that the exercise is pointless. It does suggest, however, that a certain degree of humility is in order when purporting to make such a risk-benefit calculus. Even without the ability to quantify, thinking about the relevant components of the risk-benefit analysis may help us focus on the most important questions.8 I would propose that it is not the raw potential for bias that should be of primary concern, but the harm that can result from the bias. That is, where the potential harm is great, the tolerance for bias that might result in such harm should be lower. At least one type of harm, risk to subjects enrolled in a clinical trial, is generally thought to be unacceptable (or unacceptable absent “compelling circumstances”).9 Figure 1 illustrates one way of conceptualizing the relationship between risk of bias, potential harm and the need for management. On the benefit side of the equation, it is not the ultimate value of the research that is the most significant factor, it is the investigator’s incremental contribution to achieving that value. 7 AAMC-AAU Advisory Committee on Financial Conflicts of Interest in Human Subjects Research: Protecting Patients, Preserving Integrity, Advancing Health: Accelerating the Implementation of COI Policies in Human Subjects Research pp. 24, 43-44 (February 2008). 8 Despite the shortcomings of a risk-benefit approach, it at least suggests a framework for moving from the identification of a financial conflict of interest to a decision about whether and how to eliminate or manage the conflict. The current PHS regulations require institutions to “manage, reduce or eliminate” identified financial conflicts, but give no guidance on what the criteria are for doing so. 42 CFR § 50.604(g)(2). 9 AAMC Task Force on Financial Conflicts of Interest in Clinical Research: Protecting Subjects, Preserving Trust, Promoting Progress—Policy and Guidelines for the Oversight of Individual Financial Interests in Human Subjects Research, p.16 (December 2001). The National Association of College and University Attorneys 6 What this means is that if the investigator’s participation in the research is not essential or important to its success, then there is less justification for tolerating participation with any appreciable risk of bias. Figure 2 illustrates the notion that where the specific investigator’s participation is not central to carrying out the research, or the benefits of the research are not likely to be high, there is less reason to tolerate potential bias or use substantial resources to manage or eliminate it. Conversely, where the investigator is critically important to the research and the research is important (i.e. its potential benefits are high), there is a stronger rationale for tolerating potential bias or using resources to manage or eliminate the risk of such bias. Management Strategies Conflict management strategies fall into three general categories: those designed to eliminate or reduce the bias incentive; those intended to eliminate or reduce the ability for bias to affect the research; and those designed to reduce the consequences of bias. Reducing Bias Incentive. Eliminating the financial interest entirely is usually thought sufficient to eliminate the conflict. In cases where the bias incentive is created by the prospect of future gain associated with the research, this is probably correct. Where, however, the financial interest has already been received, there may be no meaningful way to eliminate the bias incentive associated with its receipt. Where the bias may be created because of the reciprocity tendency, eliminating the prospect of future payment does not eliminate the effect. Most institutional policies implicitly assume that the risk of reciprocity bias fades with time and take into consideration only relatively recent payments (e.g., those within the past year). That is, a large The National Association of College and University Attorneys 7 payment ten years ago is thought less likely to influence decisions today than those within the reporting window. Short of eliminating the financial interest entirely, in some situations reducing the financial interest may be sufficient to reduce the risk of bias to a level thought acceptable. If the potential for gain is relatively small, then it may cease to be a conscious or even subconscious motivator. The bias incentive may also be reduced by reducing the likelihood that the research results will affect the financial interest, or by lengthening the time until any gain can be realized. So, for example, restricting an investigator’s right to sell his stock in a company until some defined time after the conclusion of the research, or until after an approved product comes to market, may reduce the strength of the bias incentive by placing the hoped-for reward further into the future. Reducing Investigator’s Ability to Introduce Bias. Here the focus is not on eliminating or reducing the reward, or its certainty, but on eliminating the investigator’s ability to make decisions that can bias the conduct or results of the research. Much of the literature on conflicts in clinical research focus on this form of management and attempt to structure or place conditions on the investigator’s role so that there is no ability for any bias to affect the research. Common examples include removing the investigator from any role in recruiting or consenting subjects, and disallowing participation in analysis of unblinded results. Reducing Consequences of Bias. These are mechanisms that do not affect the incentive for bias, or the ability to act on it, but reduce its consequences. Disclosure of financial interests and monitoring or oversight committees fall into this category, although they may also play some role in reducing the bias incentive. (Disclosure and monitoring committees may be thought to The National Association of College and University Attorneys 8 have a prophylactic effect by creating an environment where an investigator knows his work will be under higher scrutiny, thereby creating an incentive for the investigator to be even more careful to avoid bias. There is little research on whether this is true.) The theory behind monitoring committees is that if a qualified group of non-conflicted scientists periodically reviews the conduct of the research, they may detect irregularities in the research or question results that seem unwarranted. If the investigator has been influenced by the financial interest, the committee may detect error and act as a check on the dissemination of biased results. Whether such committees can detect biased research decisions depends on their qualifications, the nature and quality of the information they are given or seek out for review, and the amount of effort they devote to the review. Since such a committee typically reviews the research only periodically, if it detects potential bias it may do so only after results are published or other significant decisions based on the results have been made. For this reason, such committees in themselves seem poorly suited to situations where the adverse effects of biased decision-making are severe and may occur before review (e.g., decision about enrolling a subject in a high-risk clinical trial). Disclosure of the investigator’s financial interest in connection with publication of research results is a standard component of almost all plans for managing identified financial conflicts. Similar to monitoring committees, the theory of disclosure is that once alerted to this potential source of bias, the scientific community may be more skeptical of the reported results, more rigorous in its assessment of them, and more cautious in acting on them until they are substantiated by other investigators without such conflicts. As with monitoring committees, because the beneficial effects of disclosure occur after bias may have affected the research, disclosure alone seems insufficient where the consequences of bias may be large and may take effect before the reported results have been fully tested by the scientific community. Disclosure has the further limitation that it cannot correct bias effects that result in delaying the publication of results, or in decisions not to publish findings. Conclusion This paper is a preliminary effort to create a conceptual framework for evaluating potential individual financial conflicts of interest in research. I suggest that the process should involve assessing the nature and size of the bias incentive created by the specific financial relationship at issue, which involves an assessment that goes beyond determining the nominal size of the existing financial interest, and then evaluating the roles of the investigator that may permit introduction of bias. If the investigator has both a bias incentive and the ability to act on it in a way that affects the research, then the researcher has a conflict of interest. The process then requires an effort to compare the risk of bias and the severity of potential harm from such bias with the benefits of allowing the research to proceed as proposed, recognizing that in many situations our current understanding does not permit an easy comparison of such risks and benefits. If management appears warranted, the plan should focus on conditions that reduce the bias incentive or that reduce the investigator’s ability to make biased decisions in the research. The attached “Conflict Assessment Checklist” is a set of questions and considerations designed to aid in evaluating potential conflict of interest situations using the framework described in this paper. The National Association of College and University Attorneys 9 Conflict Assessment Checklist I. Does the investigator have a financial conflict of interest? A. Is the financial interest related to the research? 1. Can the outcome of the research directly affect the value of the interest? What is the potential size of the financial effect? What is the likelihood of the effect occurring? What is the time until realization of the potential value? 2. Can the research indirectly affect the value or expectation of a financial interest? If so, what is the connection? What is the potential size of the financial effect? What is the likelihood of the effect occurring? What is the time until realization of the potential value? 3. Can the financial interest affect the research, even if the research cannot directly affect the financial interest? If so, what is the connection? Is it likely that the financial interest creates a sense of reciprocity in the investigator? B. As the research is structured, does the investigator have the ability to make decisions that affect the research or the consequences to others? If so, in what ways? Decisions implicating safety Analysis of preclinical work that may lead to human trials Design of trials Recruitment and consenting of subjects Conduct of interventions Collection of data Reporting of adverse events The National Association of College and University Attorneys 10 Analysis of data Publication of results Responsibility for timing and presentation of results Sharing of data and developments (IP) with financially interested party Decisions affecting students or trainees Administrative decisions affecting the conduct of other activities within the institution If the answers to parts A. and B. above are “yes”, then the investigator has a financial conflict of interest. II. Risk-Benefit Analysis. Do the benefits of allowing the research to proceed outweigh the risk of bias and its associated harm? A. Risk How substantial is the risk of bias? What are the consequences of bias? Safety of subjects Data integrity Safety consequences for non-subjects Investment decisions Research resource allocation decisions Delay in progress due to delay in release of results B. Benefits How important is the research? How likely is it that research will resolve an important question? How important is the investigator’s participation to the achievement of the research objectives? The National Association of College and University Attorneys 11 III. Can the situation be managed to decrease the risk of bias to an acceptable level? Can the bias incentive be reduced? Can the size or probability of the financial interest be reduced? Can conditions be imposed that would delay realization of the financial interest? Can the investigator’s ability to introduce bias be reduced? Can any of the roles in which the investigator might introduce bias be performed by others or restructured to eliminate possible bias? Can the potential consequences of bias be reduced? Is monitoring feasible and likely to be effective in revealing bias before significant consequences occur? Is required disclosure of the financial interest sufficient to reduce the risk of bias? The National Association of College and University Attorneys 12 References AAMC: The Scientific Basis of Influence and Reciprocity: A Symposium (June 12, 2007). Available at: https://services.aamc.org/publications/index.cfm?fuseaction=Product.displayForm&prd_id=215 &cfid=1&cftoken=5C4FC7F0-E0CE-4F10-D9C5A5D26D499447 AAMC Task Force on Financial Conflicts of Interest in Clinical Research: Protecting Subjects, Preserving Trust, Promoting Progress—Policy and Guidelines for the Oversight of Individual Financial Interests in Human Subjects Research (December 2001). Available at: http://www.aamc.org/research/coi/firstreport.pdf AAMC-AAU Advisory Committee on Financial Conflicts of Interest in Human Subjects Research: Protecting Patients, Preserving Integrity, Advancing Health: Accelerating the Implementation of COI Policies in Human Subjects Research (February 2008). Available at: https://services.aamc.org/publications/index.cfm?fuseaction=Product.displayForm&prd_id=220 &cfid=1&cftoken=5C4FC7F0-E0CE-4F10-D9C5A5D26D499447 Bernadette M. Broccolo and Jennifer S. Gaetter, Today’s Conflict of Interest Compliance Challenge: How do we balance the commitment to integrity with the demand for innovation? J. Health & Life Sci. L. 1(4):1, 3-65, 2008 Jul. The National Association of College and University Attorneys 13