notes - Free Movement

advertisement

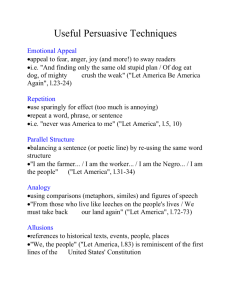

Fairness Challenges to the Points Based System Sarah Pinder and Kezia Tobin Renaissance Chambers, 5th Floor, Gray's Inn Chambers, Gray's Inn, London WC1R 5JA DX: LDE 0074 CHANCERY LANE | Telephone: 0207 404 1111 | Fax: 0207 430 1522/1050 Email: clerks@renaissancechambers.co.uk Public law principle of fairness in the Tribunal o Thakur (PBS decision – common law fairness) Bangladesh [2011] UKUT 00151 (IAC) – 23 March 2011 Mr Justice Simon & Senior Immigration Judge Latter 1. A decision by the Secretary of State to refuse further leave to remain as a Tier 4 (General) Student Migrant was not in accordance with the law because of a failure to comply with the common law duty to act fairly in the decision making process when an applicant had not had an adequate opportunity of enrolling at another college following the withdrawal of his sponsor’s licence or of making further representations before the decision was made. 2. The principles of fairness are not to be applied by rote: what fairness demands is dependent on the context of the decision and the particular circumstances of the applicant. o Patel (revocation of sponsor licence – fairness) India [2011] UKUT 00211 (IAC) - 6 June 2011 Mr Justice Blake & Mr Batiste 1. Immigration Judges have jurisdiction to determine whether decisions on variation of leave applications are in accordance with the law, where issues of fairness arise. 2. Where a sponsor licence has been revoked by the Secretary of state during an application for variation of leave and the applicant is both unaware of the revocation and not party to any reason why the licence has been revoked, the Secretary of State should afford an applicant a reasonable opportunity to vary the application by identifying a new sponsor before the application is determined. 3. It would be unfair to refuse an application without opportunity being given to vary it under s.3C(5) Immigration Act 1971. 4. Leave to remain granted by s.3C Immigration Act 1971 is relevant leave for the purposes of the Immigration Rules and the cases of QI (para 245ZX(1) considered) Pakistan [2010] UKUT 217 (IAC) and HM and 2 others (PBS – legitimate expectation – paragraph 245ZX(I) [2010] UKUT 446 (IAC) have been overruled by QI (Pakistan) v SSHD [2011] EWCA Civ 614, 18 April 2011. 5. Where the Tribunal allows an appeal on the grounds that the decision was not taken fairly and therefore not in accordance with the law, it may be sufficient to direct that any fresh decision is not to be made for a period of sixty days from the date of the reasoned decision being transmitted to the parties, in order to give the appellant a reasonable opportunity to vary his application. 6. By analogy with the present UKBA policy on curtailment of leave where a sponsor licence is revoked a 60 day period to amend the application would provide such a fair opportunity. o Fiaz (cancellation of leave to remain-fairness) [2012] UKUT 00057(IAC) - Heard on 23 January 2012 Mr Justice Blake & UT Judge King i-v) (…) vi) Where either power may be exercised it may be that the duty of fairness requires the leave to be curtailed rather than cancelled. vii) It is material to whether fairness required curtailment rather than cancellation as to whether the change of circumstance was the responsibility of the claimant or not, and whether he had endeavoured to misrepresent the position during his examination. viii) The jurisdiction to determine that a decision is not in accordance with the law because of a lack of fairness, is not to be degraded to a general judicial power to depart from the Rules where the judge thinks such a course appropriate, or to turn a mandatory factor into a discretionary one: fairness in this context is essentially procedural. Analysing the context of the decision and the particular circumstances of the applicant Examples A matter raised by the SSHD which the applicant could not possibly have had the knowledge of, such as the revocation of student license cases of Thakur and Patel. But also: o Naved (Student – fairness – notice of points) Pakistan [2012] UKUT 00014(IAC) – 6 January 2012 Mr Justice BLAKE & UT Judge Freeman Fairness requires the Secretary of State to give an applicant an opportunity to address grounds for refusal, of which he did not know and could not have known, failing which the resulting decision may be set aside on appeal as contrary to law (without contravening the provisions of s. 85A of the Nationality, Asylum and Immigration Act 2002). However: o Contractor (CAS-Tier 4) [2012] UKUT 00168 (IAC) – Heard on 13 March 2012 – Mr Justice Coulson, UT Judge Storey & UT Judge McKee 1) UKBA’s announcement in March 2011 of changes to the Immigration Rules which came into force on 21 April 2011 means that in general those who stood to be affected by those changes had adequate time to take appropriate action and hence that in general no Patel fairness issues arise. 2) This applies to the CAS-related requirement set out at para 116(da) that a new course had to be at an A-rated college and also to the CAS-related requirement set out at para 118(c)(iii) for an applicant starting a new course at below degree level to achieve Level B1 in the English Language Test in all four components. o ‘Fairness’ arguments in relation to s.85A 2002 Act Alam (s 85A – commencement – Article 8) Bangladesh [2011] UKUT 00424(IAC) – Heard 23 September 2011 UT Judge Lane (1) Where it applies, s. 85A of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 precludes certain evidence from being relied on, in order to show compliance with the Immigration Rules. (2) “Fairness” arguments concerning the application of the transitional provisions regarding s. 85A, in Article 3 of the UK Borders Act 2007 (Commencement No. 7 and Transitional Provisions) Order 2011, may have a legitimate part to play in a proportionality assessment under Article 8 of the ECHR, when assessing the strength of the State’s interest in maintaining the integrity of the Immigration Rules. o Shahzad (s 85A: commencement) [2012] UKUT 81 (IAC) – Heard 4 October 2011 Mr C.M.G. Ockelton On its true construction, Article 2 of the UK Borders Act 2007 (Commencement No 7 and Transitional Provisions) Order 2011 amends s85 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 and introduces s85A in the 2002 Act only in relation to applications made to the Secretary of State on or after 23 May 2011. o Naved (Student – fairness – notice of points) [2012] UKUT 14(IAC) Parliament enacted the exclusionary rule in s.85A against the background of the Secretary of State’s duty to act fairly, and in the expectation that the duty would be complied with. 22. Where that duty has not been complied with, the Tribunal judge can so decide and allow the appeal on that ground. In such cases it remains for the respondent to make a lawful decision in the light of the Tribunal’s determination and the information then available to her. Evidential Flexibility Policy (i) Since 2009 the SSHD has operated a policy of ‘evidential flexibility’, enabling UKBA case-owners to request missing information/documents from applicants prior to making a decision in respect of their applications. Although the policy was originally ‘secret’, it has been referred to in the following helpful documents. National Audit Office - Home Office: UK Border Agency ‘Immigration: the Points Based System – Work Routes - 15 March 2011 Paragraph 2.13 – “In 2009-10, the Agency rejected some 8 per cent (8,500) of in-country applications 2.13 and refused some 12 per cent (23,800) of all applications. From our review of cases, the commonest reason for refusal, affecting 22 of the 43 refusals in our sample, was the applicant’s failure to provide sufficient information or supporting evidence. The volume of errors and omissions by applicants led the Agency, in August 2009, to introduce a policy of ‘evidential flexibility’ which allows caseworkers to go back to applicants for missing documentation or to correct minor errors. The Agency has not, however, evaluated whether the policy is effective or being applied fairly. In response to the Chief Inspector’s8 findings of a lack of consistency in the implementation of evidential flexibility overseas, the Agency formalised its guidance to overseas posts in February 2011. We also found inconsistency of approach in Sheffield however. In addition, the Agency allows only three working days for applicants to submit extra documents. Caseworkers told us that documentation is frequently received after the application has been refused but the Agency was unable to quantify this.” http://www.nao.org.uk/publications/1011/points_based_immigration.aspx (ii) Treasury Minutes - Government responses on the Thirty Fourth to the Thirty Seventh Reports from the Committee of Public Accounts: Session 2010-12 Paragraphs 6.1-6.5: “6.1 The Government agrees with the Committee’s recommendation. 6.2 The Agency has already made changes to its evidential flexibility policy. Revised instructions have been circulated to ensure a consistent approach in decision making is adopted across all the case working units both in the UK and overseas. The revised arrangements mean that where minor omissions have been made and applicants have been asked to provide the information needed to determine their application, they will be given seven days to provide the information requested where this is necessary. This same evidential flexibility approach has also been introduced to sponsor licence applications. 6.3 In addition to the evidential flexibility arrangements, the Agency has introduced further measures to allow applicants applying in the UK to correct minor errors or omissions earlier in the application process. This approach was trialled on the Tier 1 (General) route in order to avoid rejection of applications prior to the closure of the route. The Agency plans to extend this approach across all temporary migration routes in 2011.” http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/hmt_minutes_29_32_reports_cpas_july2011.pdf (iii) House of Commons – Motion to regret – 07 July 2011 [1.38pm] Lord Avebury's motion [Column 384 Hansard] – “UKBA has issued a notice to its consultative forum, the employers' task force, stating that a validation stage is being trialled in which applicants are contacted when mandatory evidence is missing and given the opportunity to provide it before the decision is made.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201011/ldhansrd/text/1107070001.htm (iv) UKBA letter to ILPA dated 27th May 2011 In addition to the above, if seeking to rely on the policy/s.85A fairness arguments - check the standard acknowledgment letter received by the client for words to this effect, and check whether they have been complied with: “Thank you for the application by the above-named on Form Tier 4. It will now be passed to a casework unit. If there is any problem with the validity of the application, such as missing documentation or omissions on the form, a caseworker will write to you as soon as possible to advise what action you need to take to rectify the problem. (…) You should expect to receive further correspondence from us giving you instructions for the next steps in making your application. (…)” Invalid applications o Basnet (validity of application – respondent) Nepal [2012] UKUT 113 (IAC) – 04 April 2012 Mr Justice Blake & Upper Tribunal Immigration Judge Macleman 1. If the respondent asserts that an application was not accompanied by a fee, and so was not valid, the respondent has the onus of proof. 2. The respondent’s system of processing payments with postal applications risks falling into procedural unfairness, unless other measures are adopted. 3. When notices of appeal raise issues about payment of the fee and, consequently, the validity of the application and the appeal, Duty Judges of the First-tier Tribunal should issue directions to the respondent to provide information to determine whether an application was accompanied by the fee. Although Basnet concerned validity of payment, the same principles arguably apply to other aspects of an application which are said by the SSHD to be lacking. However, note the cases of Walker and Fu set out below. Where an application has been refused as invalid, there are two potential avenues of remedy. (i) Statutory Appeal Basnet involved a decision by SSHD which on its face attracted no right of appeal. Although the First Tier Tribunal declined jurisdiction, the Upper Tribunal held that it was wrong to have done so. As the Upper Tribunal found the original application in question had been valid, it consequently also found that there was a right of appeal. o R. on the application of Merrimen-Johnson v. SSHD [2010] EWHC 1598 (Admin) – 26 March 2010 Mr CMG Ockelton 9. An additional point arises on that issue. It is in my judgment very doubtful whether the question of whether a right of appeal existed is a matter for judicial review of the Secretary of State’s decision. The position is that, if there is a right of appeal, it is a right granted by statute. The Secretary of State has no power to either deny a right of appeal to somebody who properly has one or indeed to grant a right of appeal to somebody who does not have one. The position is therefore that, if the Secretary of State had wrongly concluded that a person did not have a right of appeal, the appropriate course of action would be in any event to exercise the existing right of appeal by appeal to the Tribunal rather than by challenging the Secretary of State’s decision on something on which the Secretary of State had no power to make a decision.” If lodging appeal grounds, include written submissions as to why the Tribunal has jurisdiction to hear the appeal. (ii) Judicial Review o R. on the application of Teisha Forrester v. SSHD [2008] EWHC 2307 (Admin) – 5 September 2008 Mr Justice Sullivan – as he then was Further leave to remain application as a spouse refused without a right of appeal on the basis that applicant did not have extant LTR at the time of her application having had her initial in-time application rejected as invalid due to the fee payment cheque bouncing. Judge notes that the applicant re-submitted her application ‘reasonably promptly’ In quashing the refusal, and sending the matter back to the SSHD for reconsideration (with the hope that a little common sense and humanity would prevail), Sullivan J did not dispute the SSHD’s contention that the decisions accorded with the rules but pointed out that that was not the end of the matter because the SSHD had a discretion which had to be exercised with a modicum of intelligence, common sense and humanity. Provide as much information, evidence and explanation as to any failures to comply with the rules/mandatory requirements/regulations as possible o R. on the application of Walker v. SSHD [2010] EWCH 2473 (Admin) – 29 June 2010 The Honourable Mr Justice Beatson The Claimant failed to provide passport-size photographs and so her intime application was deemed invalid and failed. When re-submitting, now out-of-time, she did not provide any explanation for her failure. Therefore, the SSHD had no material upon which to exercise her discretion and although permission was given the claim was refused. o R. on the application of Pengiliang Fu v SSHD [2010] EWHC 2922 (Admin) – 1 November 2010 Mr Justice Mitting Failure to submit photographs. Similar findings to Walker. No discretion to be exercised, mandatory requirements which were not met by the Claimant. Sympathetic comments at the end of the judgment with regards to the SSHD reconsidering the application on the substantive requirements following Pankina. It is relevant to note that this case predates both Basnet and external knowledge of the ‘evidential flexibility’ policy. Its currency may therefore be questionable, and will depend on the facts of each case. o R. on the application of Ajayi v SSHD [2011] EWHC 1793 (Admin) – 1 June 2011 HHJ Belcher Similar facts to Fu. However photographs were submitted in this case but not in compliance with guidance. Held: The mandatory requirements of the rules are essential to the basis upon which the system works (...). It is not inappropriate for a junior official to apply the policy guidance and to reject photographs where the mandatory requirements set out in the policy guidance are not met. Mitting J’s statement in Fu was adopted: that to require them to exercise discretion because of a failure by the applicant to fulfill the clear mandatory requirements in the policy guidance in this case would be to undermine the whole basis upon which the system works. He points out that it would tend to produce even more argument about individual circumstances than do the clear tick box rules. Accordingly the challenge on the basis of the rejection of the photographs must fail. o R. on the application of Mashud Kobir v SSHD [2011] EWHC 2515 (Admin) – 6 October 2011 Belinda Bucknall QC Although the SSHD had acted lawfully and within the rules in refusing a student further leave to remain, it was manifestly unfair and unreasonable in the circumstances for the SSHD not to have looked carefully at the full history with a view to exercising her discretion outside the rules rather than simply refusing it within the rules. Case details: - Initial application deemed invalid due to failure to pay full fee Failure to evidence required level of maintenance funds for full 28 days Delay in UKBA deciding application due to college being investigated and license being suspended (and reinstated) twice And two other different grounds for refusal in two other relevant applications made subsequently! The Judge noted: - - Claimant’s long and trouble-free immigration history The modest and understandable nature of the error in making the first application Claimant’s prompt and full explanation which accompanied the second application The absence of proportionality in requiring the Claimant to incur the cost and disruption of removing his family to Bangladesh, where he would be able to apply for EC in the same category and no doubt succeed The period of inexcusable delay on the part of the Defendant before processing the second application, as a result of which the Claimant lost the opportunity to promptly explain and make a compliant third application, probably in the capacity of a person with an established presence in the United Kingdom.