School of Applied Global Ethics

advertisement

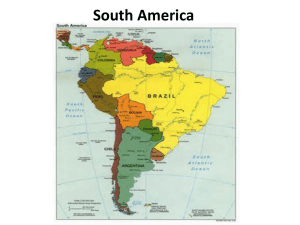

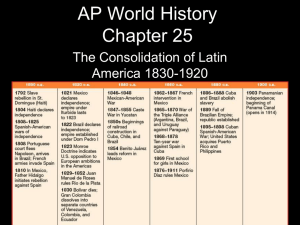

School of Applied Global Ethics Leslie Silver International Faculty Leeds Metropolitan University Research Proposal: Seeking Reconciliation after a Conflict: Argentina, a Case Study AYERAY M. MEDINA BUSTOS Supervisors: Dave Webb and Gavin Fairbairn Introduction and background to the study Between 1976 and 1983, Argentina suffered its final dictatorship in which the military and security forces took the government by force and committed gross human rights violations in the name of what was called ‘A Process of National Re-organization’. They aimed to prevail over guerrilla groups, especially over the most prominent one, ‘Montoneros’ and restrain sections of the civilian population who were demanding social reform. Events like this not only happened in Argentina, but also in many other Latin American countries, including Bolivia (1964-1982), Brazil (1964-1985), Chile (1973-1990), Colombia (1953-1954), Cuba (1933-1940, 1952-1959), Ecuador ( 1972-1979), El Salvador (1931-1984), Guatemala (1954-1986), Haiti (1991-1994), Honduras (1972-1982), Nicaragua (1936-1979), Panama (1968-1989), Paraguay (1949-1989), Peru (1968-1980), Suriname (19801988), Uruguay (1973-1985) and Venezuela (1952-1958). Although this work focuses on the Argentinean experience, the aftermath of that experience, will also attempt to draw some broader conclusions that might be relevant to other countries that are now going through similar experiences. The level of violence in what many people refer to as the ‘Dirty War’ (Bartolomei, 1991; Humphrey, 2002; Jelin, 1994; Verbitsky, 2005) was extremely high, and very much different from other coup d’etat that had taken place since 1930 in Argentina. More than 30,000 people disappeared, were hidden and/or murdered in clandestine detention centres or in concentration camps (Robben, 2005). Argentina’s cultural life was limited by political and moral censorship, an example of which was the prohibition of meetings, neither in clubs nor in private houses, and very noticeably by the censorship of the media, newspapers, radios, television (Robben, 2005). Political Science, sociology, psychology and even architecture were all believed to be dangerous because they depended on foreign influences and arose because of left-wing students and academics that had travelled widely. The military sought to create an orthodox culture, based on in a rigid set of simple patriotic values, family and Christianity. The harassment of journalists, the use of terror to silence writers, musicians and teachers, and the well-known black-listing1 of people was experienced in a similar manner as in Nazi Germany in the 1930s. The principal resistance to the Military Junta regime2 came from the trade union and youth movements. In addition there were two groups against the military regime, made up of mothers and grandmothers of the The blacklist is referred to the list perpetrators had and used in any place, can be in the trains, buses, schools and streets. This list was based in whom they called ‘subversives’, linking possible targets by common name, friendship, or any relation they found possible. 2 Jorge Rafael Videla (1976-1981), Orlando Ramon Agosti, Eduardo Emilio Massera, Roberto Viola (1981-1983), Galtieri. 1 ‘disappeared’. These women, aged between forty and sixty, had a public meeting every Thursday afternoon, to express their anguish, in the Plaza de Mayo opposite the Government House, for this reason, they came to be known as the ‘Madres of Plaza de Mayo’ (Robben 2005, see also www.madres.org and www.abuelas.org.ar) During the Dirty War, there were two well opposing defined groups: the leftist ‘Montoneros’ movement and the AAA (Anti-Communist Alliance) from the extreme right. The violence persisted, and President Isabel Peron declared a state of emergency in November 1974. In 1975, The Peron government concluded that police and security forces were not capable of preventing terrorist activities. However, instead of peace and order, the military forces had themselves brought terror and violence, starting a new coup d’etat. The Argentinean National Commission of the Disappeared CONADEP was set up in 1983 and produced the Nunca Mas (Never Again) report (Nunca Mas Never Again: A Report by Argentinean Commission, 1986). The Nunca Mas (Never Again) projects in Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, for instance, are a clear example of narratives. They seek to register into documentation and reports as an official memory of events and atrocities that occurred in those countries. In Argentina, the truth commission report Nunca Mas (Never Again) intended to be a public memory as well as the starting point for prosecution of the leaders of the Argentine junta (Humphrey, 2002). For that reasons, it can be considered as a valuable instrument to achieve justice and reconciliation. In Nunca Mas (Never Again), there is a detailed description by some survivors about what they lived through during their torture and/or imprisonment. Their narrations clearly show human rights abuses from the authorities at that time. To name the types of violations of human rights: kidnap, kidnap in front of children, torture in the victim’s home, generally in front of the children as well. Nevertheless, three decades after the publication of the CONADEP report, human rights questions continue to dominate Argentina’s political discussion. The former president, Nestor Kirchner, who was selected in 2003, has given priority to this issue, annulling previous amnesty laws and converting the Naval Engineering Academy ESMA (Escuela Superior de Mecanica de la Armada) where about 5,000 Argentineans were murdered, into a museum dedicated to the memory of the victims of the atrocities (Rohter, 2006). The incompatibility of Argentina's Full Stop Law3, and Due Obedience Law4, was expressed by Amnesty International with respect to international law and especially, with Argentina's obligation to bring to justice and punish the perpetrators of gross violations of human rights. Lee (1990) cites a ruling by the Supreme Court of Argentina on 22 June 1987, which cites the Due Obedience Law as stating that: ….members of the security forces who had tortured and killed citizens could no be prosecuted if they were acting under orders (p.1). Hence, the effect of the law was to grant amnesty from prosecution to 300 military officers. This fact caused negative reactions among most of Argentinean society. The Full Stop Law or ‘Ley de Punto Final’, was promulgated with the purpose of stopping, as the name of the law indicate, the trials against military Junta and others. President Carlos Menem later in 1989 granted a pardon to members of the military who were involved in human rights violations, as well as to those involved in military revolts and mutinies during Alfonsin’s term. Some 280 persons were pardoned and Menem justified his action saying that there was a need to ‘heal the wounds of the past’ and to create a sense of ‘national reconciliation’ (Bartolomei, 1991). Yet, the Armed Forces far from showing any signs of repentance or recognition of wrongdoing have interpreted these de facto amnesties as a vindication of their role in the anti-subversion campaign in which 30,000 people were killed or ‘disappeared’. These laws demonstrate that the search for truth and justice must continue in Argentina. The victims claim that crimes should not be forgotten and that the historical and collective memory of what had happened should be kept alive. A campaign developed to promote this in different ways to symbolize and preserve as a vivid memory the traumatic experience. The common slogan in Argentina was: ‘Ni olvido ni perdon’ (Neither oblivion, nor pardon). The methodology used to torture people and the magnitude of the atrocities that took place reminds us of what happened in the Holocaust of World War II (Roth and Patterson, 2004). The role that politics and religion 3 4 Law Nº 23,492 of 12 December 1986 Law Nº 23,521 of 4 June 1987 had at that time is important to highlight because there are unsolved issues involving the role of the Catholic Church, when it acted as an accomplice of the dictators (Verbitsky, 2005-2006). Aims of the study In this study, I aim to investigate why it is important to seek reconciliation in Argentina after its last conflict and what are the required conditions to reach it. I also seek to review the existing model of reconciliation and find out how to improve the steps, proposed by some scholars, such as apology, truth commissions, public trials, reparations payments, education, to name some of them, that are necessary to achieve reconciliation. I aim to investigate whether it is ‘not good to forget’ and why it is important to consider ‘the National Memory’. In particular, I also want to address the following questions: Research questions Principal question What are the conditions required to achieve reconciliation in Argentina? Subsidiary questions How should we deal with atrocities and violations such as occurred in Argentina if we wish to achieve reconciliation? What resources are required for the reconciliation process? What are the limits of reconciliation in Argentina? Methodology Primary data collection The data will be gathered via interviews, combined with historical documents and archives analysis. I will also analyse the political and social dynamics and development of Argentina during the years 1976 and 1983. The types of interviews I wish to use are the semi-structured and unstructured interviews. These types of interviews will enable me to discus and talk face to face with people who have experienced and lived the conflict in Argentina, and can give detailed information about it.