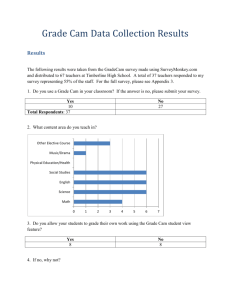

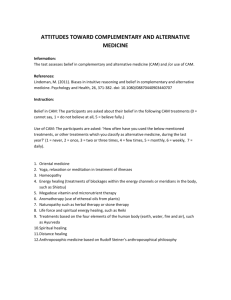

Cam Artefacts

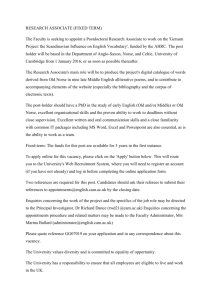

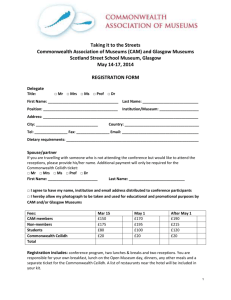

advertisement