Isolation and Fractionation of Subcellular Organelles

advertisement

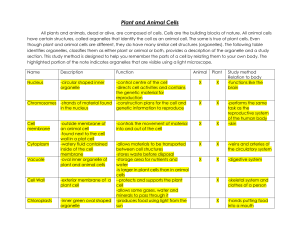

BS2510 Isolation and Fractionation of Subcellular Organelles An important aspect of the study of the Biochemistry and Cell Biology of eukaryotes is the study of the function of cell organelles. This often means that organelles have to be purified so that the are free of other cell components with the minimum damage to the structure and function of the organelle. Various methods can be used for the disruption of the tissue depending on the size of the cells, the collagen content of the tissue (or in the case of plant cells, the thickness of the cell walls). Liver is perhaps the most easily fractionated of all tissues with relatively large cells (10 -20 µm) which are readily broken. The homogeniser used is a power -driven Teflon homogeniser (Potter-Elvehjem) rotating in a closely-fitting glass tube. The size of the gap between the pestle and the glass is such that the rotating pestle applies a shearing force which breaks open the cell releasing the contents without breaking the organelles. The degree of homogenisation of the tissue depends on (a), the speed of rotation of the pestle, (b), the clearance between the pestle and the glass container, (c), the number of strokes of the pestle and (d), the thrust force applied. If the pestle is too tight or too many strokes are applied the organelles will be damaged. The development of the best procedure for the homogenisation of any tissue for the preparation of intact organelles is a matter of the application of scientific principles plus trial and error based on experimentation. Th other important factor for the isolation of intact organelles is the composition of the homogenisation medium, particularly the osmotic strength of the medium. As with intact cells, a hypo-osmolar medium causes organelle swelling and breakage. Usually the organelles are more susceptible to osmotic damage than the cells from which they are derived. The homogenisation should therefore be performed in an iso-osmotic medium containing an inert substance, for example 0.25 M sucrose (or mannitol). Sometimes iso-osmotic 0.1M KCl is used, reflecting the cytoplasmic concentration of the salt in most cells. Usually a dilute buffer is also added to prevent large fluctuations in pH which may damage organelles. The maintenance of a pH gradient is especially important in the function of some organelles. Chelators of divalent metal ions such as EDTA or EGTA are often added because such metal ions may damage organelles. Centrifugation of subcellular organelles Once the cell-free homogenate has been prepared the next step is the use of differential centrifugation to separate out the various organelles on the basis of their size and density (see Table1). 1 Table 1. Size and Density of Some Sub-cellular Organelles from Liver Size m Density (g/cm3) (in sucrose medium) Nuclei 3 - 12 >1.30 Mitochondria 0.5 - 2.0 1.17 - 1.21 Lysosomes 0.2 - 0.4 1.20 - 1.22 Peroxisomes 0.2 - 0.5 1.23 Endoplasmic reticulum vesicles (microsomes) 0.05 - 0.30 1.15 (smooth ER) 1.22 (rough ER) Golgi stacks ~ 1.0 1.10 - 1.13 Golgi vesicles ~0.05 Plasma membrane sheets 20 1.15 - 1.19 Plasma membrane vesicles 0.05 < 1.17 Differential Centrifugation Particles may be separated on the basis of their size and density by differential centrifugation. Relative Centrifugal Field (RCF) This is the force applied to a particle which is in a centrifuge rotor, which is rotating about a central pivot at a given speed. RCF(g) =1.12 x r x (rpm/1000)2 Where r = distance of particle from the centre of rotation and rpm is the speed of rotation in revolutions per minute. It follows that the g force is greater at the bottom of the tube than at the top and therefore particles near the bottom of the tube sediment faster than those at the top. This is one reason why some centrifuge rotors are designed to hold the centrifuge tube at a steep angle, to reduce the difference in g force at the top and bottom of the tube. 2 The rate of sedimentation of a particle (v) is given by the following equation: v= 2 r 2p ( p - m )g 9 where rp and ρp are, respectively, the radius and density of the particle, ρm the density of the medium, g is the centrifugal force and η is the viscosity of the liquid. The rate at which a particle is sedimented is therefore dependent on : (a) (The radius of the particle)2 and is therefore related to the cross-sectional are of the organelle. (b) The difference between the density of the organelle and the density of the medium in which the organelle is suspended. When the two densities are equal then the organelle will not sediment regardless of the g force applied and, indeed if the density of the medium is greater than that of the particle, then it will tend to float towards the top of the tube. (c) The g force applied ~ proportional to (rpm/1000)2. (d) The sedimentation rate is inversely proportional to the viscosity of the medium. The higher the viscosity, the slower the rate of sedimentation. Isolated organelles sediment at different rates related to their size and density (See Table 2) Table 2. Organelles sedimented by centrifugation at increasing speeds [1] 1,000 x g (10 min) Unbroken cells, nuclei, plasma membrane sheets, heavy mitochondria plus smaller, trapped particles. [2] 3,000 x g (10 min) Heavy mitochondria, plasma membrane fragments plus smaller, trapped particles. [3] 10,000 x g (20 min) Mitochondria, lysosomes, peroxisome, some Golgi membranes and rough endoplasmic reticulum. [4] 100,000 x g (60 min) Membrane vesicles derived from smooth and rough endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi vesicles and plasma membrane vesicles. [5] 100,000 x g Supernatant Cytoplasmic components plus any soluble organelle components released during homogenisation and fractionation. 3 Characterisation of Organelles in Fractions Organelles may be identified by their characteristic appearance under the electron microscope (see Molecular Cell Biology, Chapt. 5 Lodish et al.2000,2004) or with fluorescent-tagged antibodies raised against specific organelle components or by measuring specific marker enzymes. Marker Enzymes Each organelle has a specific role to play in cellular function and it therefore follows that certain components (including proteins and enzymes) are only found associated with one organelle. This is not the case for all proteins as there is an increasing body of evidence that some proteins are translocated from one cellular compartment to another as part of the normal cell function. However there are certain enzymes that are easy to measure which are located primarily in a single type of organelle or cell compartment. These are known as marker enzymes. The genes for these marker enzymes also code for a leader or signal peptide which directs the particular protein into a specific cellular location. The assay of marker enzymes can be used to track the fate of a particular organelle during a fractionation procedure. Let us examine how marker enzymes may be used to identify organelles, starting with a structure which is not an organelle as such but that does have very specific and important functions. i.e. the plasma membrane. Plasma membrane The plasma membrane has many essential functions, including transporting nutrients into the cell and removing waste products, preventing unwanted materials from entering the cell and preventing the loss of essential metabolites as well as maintaining the intracellular ions, pH and osmotic pressure of the cytoplasm. A good marker for the hepatic plasma membrane is 5’ nucleotidase: AMP adenosine + Pi This activity is located on the extracellular surface of the plasma membrane of the liver – its function here is not entirely clear. Plasma membrane fractions are often prepared by homogenisation of tissue in dilute (1mM) NaHCO3. depending on the degree of homogenisation of a tissue the marker enzyme tends to be located in large sheets of membrane fragments which tend to sediment at low speed (1,000 x g) along with nuclei, whole cells and large mitochondria. However this fraction may be sub-fractionated on a discontinouous sucrose gradient where the fraction suspended in 0.25M sucrose which is overlaid on 37% sucrose which, in turn, is overlaid on 57% sucrose and centrifuged at 75,000 x g for 16 h. The nuclei and whole cells sediment to the bottom of the tube, mitochondria accumulate at the interface of the 37% and 57% sucrose, while the plasma membrane accumulates at the interface of the 0.25 M sucrose and the 37% sucrose (Fig 1a). Much smaller, plasma membrane vesicles can also form on homogenisation which appear in the ‘microsomal’ or 100,000 x 4 g pellet along with the endoplasmic reticulum. This fraction can also be sub-fractionated using the discontinous gradient described above with the plasma membrane vesicles accumulating at the 0.25 M sucrose / 37% sucrose interface (Fig 1b). Fig 1a. Subfractionation of ‘nuclear’ pellet, containing plasma membrane fragments Fig 1b Subfractionation of microsomal pellet, containing plasma membrane vesicles Why might you need to isolate pure plasma membrane preparations? To study various aspects of plasma membrane function for example: Hormone receptors: adrenergic, glucagon insulin receptors etc Signal transduction components G-proteins, adenylate cyclase Transport proteins Glut-2, Glut-4, Na+K+ATPase, Ion channel proteins Can you think of any other functional components of plasma membranes? To show the plasma membrane localisation of these proteins you would need to show that they co-fractionate with the 5’nucleotidase. Having established that a protein is associated with a particuar fraction, it is possible to use this as a first step in a purification procedure. The next step is often the solubilization of the membrane-associated protein with a detergent. Endoplasmic Reticulum The ER is the network of channels for proteins targeted for specific modifications rather than cytosolic proteins. There are two types of ER visible under the electron microscope; the rough ER has ribosomes attached and is the site of protein synthesis while the smooth 5 ER does not have ribosomes but has enzymes involved in lipid synthesis and steroid metabolism . A marker enzyme for liver ER is glucose-6-phosphatase which catalyses the following reaction: Glu-6-P Glucose + Pi This enzyme plays a key role in the regulation of glucose output by liver and thus in control of blood glucose. It is the final enzyme of the gluconeogenic pathway and also in the mobilisation of glycogen in the liver. If the enzyme activity is determined in a microsomal fraction the activity is rather low unless a detergent is added. This is because the active site of the enzyme is on the inside of the microsomal vesicles. Glucose-6phosphate uptake by the vesicles is rate limiting; there is a specific Glu-6-P transporter which is essential for the activity because otherwise the ER membrane is impermeable to the phosphorylated derivatives. The activity of Glu-6-phosphatase appears much greater when detergent is added to permeabilise the membrane. This phenomenon is known as LATENCY and this can also been shown for enzymes located in other organelles (e.g. lysosomes) when exposed to hydrophilic substrates. Separation of Rough and Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum This is relatively easily done, a 10,000 x g, post-mitochondrial supernatant is prepared in 0.44 M sucrose and layered on to 1.3 M sucrose (44%, = 1.20) then centrifuged at 105,000 x g for 7 h. The rough microsomes sediment to the bottom of the tube while the smooth ER remains suspended at the top of the 1.3 M sucrose DR Davies 2005 6