Rudolf De Rijk, euskaldunen Holandako adiskidea (1937

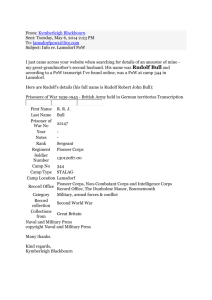

advertisement

RUDOLF DE RIJK, THE DUTCH FRIEND OF THE BASQUES (19372003) Rudolf and Virginia de Rijk lived on a small street that always amazed visitors from the Basque Country, because right in the window of their front door, where everyone could see it, there was a Basque flag ready to greet people. The house looked like the Basque Consulate in Amsterdam. And in a certain sense it was. Rudolf was always an excellent consul for us, although his activity was confined to linguistic matters. But that amounted to a lot, because one of our fundamental signs of identity is our language. The de Rijks were our friends, always welcoming us and treating us with warm kindness whenever we dropped in at Newtonstraat. And that warmth lives on now with Virginia, who still welcomes us in that same house. This is the first thing we are grateful for. Those tall, narrow houses that are so prevalent here in The Netherlands, due to your efforts to gain land from the sea, are surprising for us Basques. We too live next to the sea, but our houses have an entirely different layout. I always used to wonder how Rudolf and Virginia would cope when, with the passing of years, age eventually made it hard for them to climb those steep stairs, which at first glance looked like they were made for a giant. I think I counted the steps on one of my vists there: 16 to the first landing, and another 15 beyond that. And each step was so narrow that at first it was hard to fit my whole foot on it. Unfortunately, our wonderful friend Rudolf never reached the age when he would have to cope with the problem that worried me so much, but which never even crossed his mind. The grave illness that marked his final months did not, however, keep him from completing, or almost completing, a work he had begun years earlier — a long, concise, absolutely thorough work written in an apparently simple style yet conveying the profound knowledge of spoken and written Basque that Professor de Rijk was known for. Today we are fortunate to present, in the very University where he taught for so many years, this magnificent book. Standard Basque is a volume with a long history behind it. The process involved in publishing it reminded me of the patience with which Rudolf worked to fill its pages. But this grammar could never have been published in a completed state without the countless hours spent by Virginia de Rijk in going over the text again and again, checking each of the quotes (not an easy task, as you can imagine), copy-editing every page until the manuscript was in the perfect condition required by MIT Press. Here before me I have photocopies of the text as left by Rudolf. It’s a final draft, but there are still many hand-written annotations, and I have to confess my amazement at the enormous patience and tenacity with which Virginia de Rijk-Chan undertook the task. A job that merits even higher praise if we remember that her training had nothing to do with linguistics. As she herself says in the Acknowledgments, other people also contributed in one way or another to the book’s successful publication. I will only mention Armand de Coene, with whom I have had the most contact. Armand had the monumental task of dealing with the glosses — glosses for nearly 4,000 1 examples — in a language which, as you all know, is morphologically quite complex. All of us should pay him a public debt of gratitude. Rudolf and Virginia were our friends, the friends of many Basques whom they visited with relative frequency. I met them years ago, first Rudolf and then Virginia. My first encounter occurred when, with a close friend, I attended a talk that Rudolf de Rijk gave at the Universidad de Deusto in San Sebastián. I’ll never forget it. It must have been at the end of 1979, or early 1980, because it got dark early, but the talk stirred up an amazing appetite and generated so much warmth that it inspired a memorable dinner and launched a series of serious tête-à-têtes thereafter. It was astonishing: here before us was a foreign linguist with a pronounced accent speaking fluent Basque, writing phonological formulas and easily explaining his hypotheses and fielding questions with a torrent of examples drawn from different dialects. Such a feat was not at all common back then, in a period when we were still just emerging from the Franco dictatorship. As you know, the Franco regime harshly persecuted the use of Basque in many areas of the country, regardless of the fact that it was the only language spoken by many of its citizens. Fortunately, things have changed since then. Rudolf, “that Dutch linguist who speaks Basque and knows the dialects”, was making a name for himself among us, just at the time that Basque Linguistics was beginning to be taught at the university level, thanks to the decisive contributions of Koldo Mitxelena, professor at the University of Salamanca first, and at the University of the Basque Country during his final years. Mitxelena is unanimously recognized as the most important and influential Basque linguist ever produced by the Basque Country. He belonged to that species of erudite scholars which is now quickly disappearing. Koldo Mitxelena also died unexpectedly at a relatively young age. Let me just mention that in 2008 a small selection of Mitxelena’s works will be published in the Basque Classics series by the University of Nevada at Reno, followed by another selection to be brought out by John Benjamins. In any case, through Mitxelena, I contacted de Rijk for a more personal reason. Mitxelena was the director of my Ph.D. thesis and had suggested that de Rijk should be on my dissertation committee. I agreed and felt it would be an honor for me, but actually was a bit hesitant, because I had only seen Rudolf at the San Sebastián talk, and to me, as someone just starting out, he seemed so famous as to be way out of my range. The truth is that earlier I had discussed him at length with another professor that all of you know well, Ken Hale, a wonderful dear friend whom I and my family will never forget. I had worked with him on many occasions at MIT, and he gave me many good pointers for my thesis then and later, when he visited us at home. As you know, Ken had directed Rudolf’s thesis on relative constructions in Basque, and he also knew Mitxelena, one of de Rijk’s main references in the Basque Country. The truth is that it was really fun to witness their conversations. They each had had very different training, but they respected each other very much and had great discussions that were not confined just to linguistics. I remember 2 a long one, over a cup of coffee, about Australian dogs, for example. Rudolf’s work on relative constructions, which Mitxelena praised very highly, is still a standard reference for Basque linguists. So, through Ken Hale and Koldo Mitxelena, I was finally able, still with some anxiety, to approach professor de Rijk and invite him to form part of my dissertation committee — three renowned professors for one lowly student. Forgive me for these personal notes, but I want to share with you a few more details about this incident. In contrast to some countries, in Spain the defense of a thesis can be a very tough hurdle, and I was quite nervous about what might be in store for me. So, to help pave the way, the summer before the actual defense I came to Amsterdam with my wife and delivered a copy of the thesis to de Rijk. We were stunned by the welcome that we received. In our culture, no student could expect such friendliness from an important professor. So we had a good visit, but just to be safe, I asked de Rijk whether we could meet again before the defense so that he could explain any problems that he detected in my work, to give me time to prepare for them adequately. The upshot was that we met in his hotel in Vitoria and talked for nearly two hours, and to me he seemed like kindness personified. I know he’d studied the dissertation in detail, because he made many observations, but most were small details or notes pointing out things that he had liked. I couldn’t believe it, because now I was sure that the thesis would be approved. Rudolf truly was, as our great poet Antonio Machado would have put it, a man who was good, in the best sense of the word. I still had to defend the thesis, and with Mitxelena chairing the committee this wasn’t going to be easy, but things went as I had hoped. And naturally, when the thesis was published, the prologue was written by Rudolf de Rijk, another immense honor that I will never forget. And now, at the generous request of Virgina de Rijk, I have had the further honor of writing the prologue for this magnificent grammar. I am sorry for injecting so much personal detail here, but I wanted to take the occasion to pay homage and express my deep, abiding admiration and respect for three remarkable people: Mitxelena, Ken Hale and Rudolf de Rijk. The works on Basque authored by De Rijk join the ranks of others written by foreign linguists concerned with the study of Euskera, which is the name we give to our language: Wilhem Humboldt, Vinson, Van Eys, Schuchardt, Uhlenbeek, Faddegon, Sternpf, prince Bonaparte, Dodgson, Linschmann, Winkler, Gavel, etc., some of whom taught, I believe, at this very university. Special mention should be made of the latest of these, British linguist Robert Trask, who has also recently passed away. But Rudolf’s merit is greater, because he approached the study of Basque at a time when, in contrast to all the others, there were finally true Basque experts trained in Basque universities, who had a much better knowledge than earlier generations not only of Basque, but of the tools needed to describe it and to explain their hypotheses and theories with detachment. But, needless to say, Rudolf was able to meet them on equal ground. Because in addition to his solid linguistic training acquired at MIT, he was proficient in Basque from 3 the age of 25, when he published in this language his translation of a chapter from the Diary of Anne Frank. A short time later, he also published a review of one of the fundamental works by Mitxelena: Fonética Histórica Vasca. And these were followed by numerous articles on Basque syntax and phonology that are still being read and quoted today by Basque linguists. And he also started, way back then, on this grammar that you now have in your hands. It is the result of 40 years of work, with chapters written in different versions and in different languages. When I visited the De Rijks after his illness was diagnosed, I agreed to get this unfinished work published, although at the time I did not know how I would accomplish it, nor whether I would actually be able to fulfill the commitment that I had just acquired. Rudolf suggested Euskaltzaindia (the Academy of the Basque Language) as the publisher, but I thought we should try for something more ambitious and suggested a British or American publisher, to ensure that the volume would be distributed world-wide. In the end as you know, this grammar, so peculiar in its conception and extension, was brought out MIT Press. Rudolf was a man of great generosity and kindness. I will mention only examples concerned with linguistics, without citing things like the De Rijks’ regular donations over the years to a medical post in Bangladesh. For many, many years, Rudolf always placed at our disposal the chapters that he was so patiently working on. There was no reason why he should, but he happily shared his progress with several Basque linguists. His questions were endless, but endless above all was his enormous capacity to concentrate imaginatively on basic problems. He always zeroed in on the most problematic issues, as we were reminded almost every Saturday morning at about 11 a.m. when our home telephone would ring with a call from him. In this way we witnessed how the original chapters were reworked and rewritten, only to be reworked and rewritten again with further details. It was this painstaking thoroughness that kept Rudolf from completing his work. Standard Basque contains 27 chapters written and finished in English by Rudolf himself. To these have been added another 6 chapters based on versions left in an incomplete state. But although unfinished, they do contain a huge amount of information on practically all the central points of Basque grammar: when they are not treated expressly in a given chapter, they are included indirectly in others. The grammar also has another feature that is not very common in this type of work. It was conceived as a book for people who want to learn Basque. In each chapter, following a description of some aspect of Basque syntax or grammar, there is a vocabulary with the terms used in the chapter plus some exercises for the student to work through. And the descriptions of the grammatical problems are unusual too, because they include numerous lists providing a great deal of information about lexicography, morphology or syntax, which prove to be highly useful (see, for example, chapter 12 on “Transitivity”). But the same thing happens in many other chapters. Actually, although it may occasionally look like a method for learning Basque, those of us who already speak the language will learn a lot from it. Rudolf was a linguist with a fine nose for sniffing out problems, and he has left us an invaluable legacy. 4 For more than 25 years, I have been working with other Basque linguists on a descriptive grammar of Basque. We are now writing the seventh and last volume of the grammar, which we hope to see finished, in this first phase, within two years, although at the same time we are revising all the volumes. I am sure that Rudolf will provide us with much material for reflection, and that our grammar, which he was very familiar with, will be the better for it. Some final words of gratitude: thanks to those who organized this welldeserved act of homage to Rudolf on the occasion of the publication of Standard Basque. And thanks to Virginia for her enormous help. And of course, the profound gratitude of all of us to Rudolf De Rijk, the Dutch linguist and friend of the Basques. Rudolf, I’ll repeat here the words that I said when we spread your ashes on one of the Basque mountains dearest to your heart, at Urkiola: Utzi diguzun irudimenarekin, utzi dizkiguzun lanekin, beti izango zaitugu hurbil, euskaltzale eta euskaldun, euskaltzale eta euskaldunok (You left us your intuition, you left us your work, you will always be with us, the Basques, our fellow Basque speaker and friend). Leiden, January 23, 2008 Pello Salaburu 5