Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement

On the possibility of diminishing the Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus) population

through intervention in the adult geese in Sabi River Sun golf estate and White River

country estate.

Marieke Bastiaansen

Research Traineeship Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Hans Heesterbeek and Celia Abolnik

04-10-2013

Aantal woorden: 4.825

Abstract

The population of Egyptian geese (Alopochen aegyptiacus) in South Africa is growing. Egyptian geese

are normally not seen as ‘pest birds’, but for farmers and managers of golf courses and housing

estates they are increasingly becoming a problem. There has been little previous research on the

population of Egyptian geese in South Africa and methods of control. We conducted a research study

on the population of Egyptian geese in two areas of Mpumalanga: Sabi River (SR) Sun golf resort in

Hazyview and Pine Lake (PL) resort in White River. We counted the Egyptian geese spread over these

areas regularly starting the last week of June 2013 till the last week of August 2013. We found a

considerable difference between the two locations. In PL there is one big group and some pairs

spread over a nearby dam, and in SR there are just a few little groups and also pairs spread over the

course. Both resorts see the Egyptian goose as pest birds and have tried several methods to chase

them away. These methods have been discussed with the managers and, in this report, compared

with knowledge generated in previous studies. Using dogs to chase the geese away seems to work

best. However, the growing population of Egyptian geese remains a problem. To find a workable,

good solution for diminishing their number in South Africa, more research is necessary, particularly

on the local characteristics of the species concerning survival maturation and reproduction.

Keywords: Egyptian goose, Alopochen aegyptiaca, population reduction, population size, South

Africa, Mpumalanga

Introduction

The Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiacus) is widespread in Southern Africa and has also been

introduced to England and The Netherlands where they are acclimatizing well. They are of the family

Anatidae (swans, geese and ducks), and to the half-family Tadorninae (half-goose). It is a large buff

and brown duck with a dark brown spot around both eyes and on its breast. The neck ring bears the

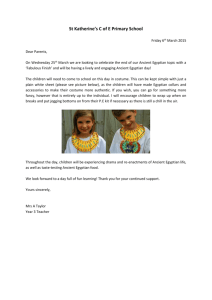

same color. The young birds lack these dark-brown coloring. (See figure 1 for details)

Figure 1a.

1b.

1c.

1d.

Figure 1a shows a female adult Egyptian goose. Notice the dark-brown spot on the breast and around

the eyes. Figure 1b shows an adult male Egyptian goose. Notice the dark-brown spot around the eyes

and the neck ring. Also the different colors in their plumage is clearly visible. Figure 1c shows a nineweek old young. Notice the lack of the spot around the eyes and on the breast. Figure 1d shows a

hatchling.

The Egyptian geese do not like forested areas. Rather, they can be found in meadows, grasslands and

agricultural fields as long as there is water close by like a river, dam, pond, wetlands or a lake

(Jensen, et al., 2002; McLachlan and Liversidge, 1940). Egyptian geese stay together their whole life,

which can last 15 years (Hockey 2005, Jensen, et al., 2002). When they reach the age of two years

they can start to make nests in a wide variety of places, like a hole in the ground, on top of old nests

of other birds (like the Hamerkop), on houses, and in holes of trees (Hockey, 2005). The females lay

between five and eleven eggs, which will hatch after 28-30 days of incubation. The hatchlings can fly

after 70 days of age and reach their sexual maturity within two years (Perlo 1999).

Egyptian geese have a growing population, possibly because of an increase in suitable habitat, such

as golf courses, bungalow parks and farming areas. These developments give a rise in space for the

young birds to stay, in food, and in nesting places. Often there are no dominant couples around

because of human intervention, there’s enough food, and there are not very many predators.

Farmers increasingly complain about crops getting damaged (Magnall & Crowe, 2001). Also on the

golf courses the Egyptian geese are causing problems. A survey of the residents and members of the

Steenberg Golf Estate, Cape Town, during April 2012 by Little and Sutton showed that the majority

considered the geese a problem on the golf estate. 52% of the respondents thought it is a severe

problem and the majority of the respondents thought that there should be a reduction of 50% or

more in the goose population (Little & Sutton, 2013). A lot of golf courses and estates struggle with

an overpopulation of Egyptian geese. The geese make a lot of noise especially in their breeding

period and soil the grass and swimming pool--where children are playing--with their droppings. Their

droppings contain acids which erode the material of the swimming pool (Ramezanzadeh et al.

2009). Their droppings also contain grass seeds which contaminate the golf course’s green. The green

consists of a special grass type and costs a lot of effort to get and keep it in perfect condition. Other

grass types, seeds of which are spread by geese droppings on the green, are problematic for golf

course managers (C. Nel, personal communication, 27 June 2013).

To reduce the number of Egyptian geese, multiple methods have been tried. Culling does not seem

to work, poisoning and shooting had no lasting effect (Bronwyn, 2010). Because the Egyptian geese

are still causing problems, it is important to find a way to decrease the population. Before starting

research to discover the best method to decrease the number of geese, it is important to survey the

current situation. We chose to do that on two locations, and examined in which part of the

population intervention could have effect. There is very little knowledge about the local

circumstances. This research is based on initial fieldwork and studies from the literature. It is the first

research project in these areas.

It is also important to do a population study because of the spread of Avian Influenza. Evidence

indicates that the Egyptian geese spread the Avian Influenza to ostrich farms. The geese might carry

low pathogenic avian influenza strains, which then mutate in high pathogenic avian influenza in

ostriches. With risk for the human health care and export bans for the ostriches (Abolnik et al, 2010;

Cumming et al, 2011).

Material en methods

Study area/field sites

The research locations where two resorts from

the Tsogo Sun company. Pine Lake resort (PL)

and Sabi River Sun golf estate (SR).

Pine Lake resort

PL is a timeshare resort near White River,

Mpumalanga, South-Africa. (figure 2) This resort

is situated next to Longmere Dam. A 250m x

3,6km dam with lots of different kind of shores.

There are 34 chalets on the property, all with a

view on the dam. Between the dam and the

chalets is a band of LM grass of 50x200m long.

In the middle of the row with chalets is a

swimming pool of approximately 10x20m. The

shores of the dam bordering on PL vary from

sprinkled LM grass and reed.

Figure2: Illustration of the research area. Within

the green lines is Longmere Dam. Pine Lake

Resort is marked with a red dot.

Longmere dam

Longmere dam is a big dam of about 3.3km

length, with different kind of shores like grass,

sprinkled LM grass, shrubs, forest and reed. In the first kilometer there are two resorts, a canoe

sports club and a lot of houses. After this first kilometer there are no houses anymore but mainly

forestation, grass and shrubs. Because geese do not prefer an area with limited visibility (Hockey

2005) we used the amount of reed as a guideline for the most northern point of our research area.

(S2515.339, E 310.192) The lowest point is the end of the Dam and the side borders the overview

over the edges out of the dam. At the opposite site of PL stands a big house with a garden (Figure 3).

One part of 55x7m borders on the dam and is separated from the main garden by a fence. This piece

of LM grass is also surrounded by a fence to keep predators out.

Figure 3

Pine Lake Resort, the red arrow shows the house on the opposite. Remarkable is the obvious green

band of grass.

Sabi River Sun golf estate

SR is a timeshare resort with a hotel, 104 chalets and an 18 hole golf course in

Hazyview, Mpumalanga, South Africa. (figure 4) The chalets

and five swimming pools are spread out over the domain.

On the golf course are several ponds. Each pond has a

different shore and enjoys a different popularity among the

geese. It is important to realize that there are a lot of

different kinds of grasses on the golf course. Meadowgrass

and permanent grassland is highly popular among geese

(Magnall & Crowe 2001), and there is plenty of those on a

golf course. The grass is sprinkled every day to ensure it

stays green. (C. Nel, personal communication, 27 June

2013) One of the borders of the golf course is a river, which

ends in a lake. In the river there are some small islands with

grass and sand. The whole side of the river is separated

with electricity wire to keep the hippos and other wild

animals outside. Also this lake and a little bit of adjacent

land, is surrounded with a wire to prevent the hippos from

attacking the guests.

Figure 4: illustration of the research area. Within the green

lines is Sabi River Sun golf resort.

Surveys

Data was collected from the last week of June 2013 to the last week of August 2013. Both study

areas have been visited multiple times in this period.

There has always been a big group of geese at the parcel opposite of PL. We counted these geese the

first days and thought it was a stable group. We decided to count them each couple of days. We

noticed that the group was less stable than we thought so we changed the method and counted

them every day, if possible. The Egyptian geese where counted from a rowing-boat or from chalet 24

with a binocular. From these points we had a good visibility on the flock of Egyptian geese.

In front of the chalets in PL we counted a few pairs that defended their territory. To find the other

pairs we took a rowing-boat. We sailed close on a shore side to the end point of our research area

and sailed back on the other shore side. When it was necessary, a binocular was used. We remodeled

the data in a map so we could see if we spotted the pairs before on the same place.

In SR we counted each day. We walked through the golf course and noticed how many Egyptian

geese we counted and where they hang out. The data was remodeled in a map so we could see

where the couples, groups and singles hung out.

Counting protocol

We walked/rowed on every part of the property that was reachable, and counted the Egyptian geese

that stay on the ground. We did not count flying birds. We maintained the same route every time,

but were aware of new possibilities where geese could possibly be found. Every repeated counting

was at more or less at the same time of day (Sovon Vogelonderzoek Nederland). When two Egyptian

geese where together without others, we noted them as a pair. When two Egyptian geese where

chasing others and made their typical ‘victory-dance’, we noted them as a pair. When just one

Egyptian goose was doing this and protecting a territory, we noted this goose as probably part of a

pair assumed to have a nest. Multiple geese close to each other without fighting were noted as a

group. Sometimes we saw just one isolated Egyptian goose. These ones we noticed as a ‘single’.

Results

Figure 5 shows the number of geese around PL. The first measurement was in June 2013. The

number of geese was approximately 129 {121, 135, 130, 127 and 135} in the first measurement.

Since the 5th of July there was a decrease in the number of geese and the values dropped to between

67 and 79. In the third period of measurement the number of geese increased and reached a peak of

198. In the last period the values were very different and fluctuated between 185 and 118.

Figure 5, number of Egyptian geese around Pine Lake resort.

Figure 6 shows the number of couples in PL. The number remained roughly constant at around 7

during the study period. We did not find any nesting places or Egyptian geese standing alone and

guarding their territory. The couples were widely spread over the area. (Cornelissen 2013)

Figure 6, numbers of couples around Pine Lake resort.

Sabi River Sun Golf resort had a very different population of Egyptian geese compared to PL. There

were different and smaller flocks. Figure 7 shows the total number of Egyptian geese in a flock

around SR. We stayed for two consecutive weeks in July in SR. The data in August have been

generated during day trips. There seems to be an increase in numbers in the two-week period.

Altogether there are less Egyptian geese around SR in contrast with the Egyptian geese living in the

flock in PL.

Figure 7, Numbers of Egyptian geese living in a flock in Sabi River Sun golf resort.

In Sabi River Sun golf resort we detected a difference in couples. Based on that we made a

subdivision. Figure 8 shows that we started with one couple with older young and ended with three

couples with young. In the period before the 26th of July we suspected couples of having a nest. We

saw one male guarding his territory every day and in the same area, and on the 26th of July we

discovered 9 hatchlings. There were days we counted two couples, and the peak counting was eight.

Figure 8, number and division of couples in Sabi River Sun golf resort

Discussion

Data limitations

Figure 5 shows an apparent decrease in number of Egyptian geese from the 5th of August. In that

period the weather was colder, and it rained for some days. This observation stands in contrast with

the data to the period of the 31th of July till the 6th of August, in this period the weather was very

good. This limitation is also applicable to table 3. When we started the research at SR it was colder

than a few days later on. We did not take precise measurements of the weather conditions, and are

not able to statistically test whether the conditions influence the number of geese that can be

spotted. We can therefore not say whether the geese were simply elsewhere for the colder period,

hence explaining the apparent decrease. Actually, research of Lensink showed that in severe winters

the population size of Egyptian geese decreased (Lensink 1999). Although this was a research in the

Netherlands, it would be quite reasonable for the decrease we saw during the colder days in South

Africa to be attributed to altering weather conditions. Where the geese reside at colder days is

unknown.

When breeding pairs have settled on a territory, they normally stay in that area (Sovon

Vogelonderzoek Nederland). Figure 6 and 8 show a lot of fluctuation. When the Egyptian geese were

all settled and ready to make a nest one would suspect more constant results. During the research

we noticed a lot of fighting pairs. They were defending their territory with a lot of noise and physical

attacks. Probably if the research had been delayed by a month there would be more constant data,

or when the research program had last longer. The Egyptian geese would have been settled and

would have stayed on their territory. Delaying the research period until later in the year may also

lead to a higher number of couples, nests, eggs and hatchlings. Possibly, the period chosen for our

study was too early, possibly also influenced by the local climate and weather conditions in 2013.

It is also possible that Egyptian geese were not seen-- or were counted multiple times. However, the

area was explored very accurately and every time in the same way by the same people. This method

could be made more secure by using rings. When the Egyptian geese in the research area could be

ringed, there should be no misunderstanding if an Egyptian goose was already counted or not. It

would also be clearly recognizable if it is actually the same pair of Egyptian geese we spot every time

on the same place. And with that information one can make clear if the above-mentioned is actually

their territory or if they are just passers-by. However, it would take a significant effort to ring all the

Egyptian geese in PL and SR. Unlike the relatively tame Egyptian geese in the parks in the

Netherlands which are quite easy to ring, the Egyptian geese in above-mentioned resorts are not so

tame. These geese are scared of people and fly away when humans approach. M. Ndlovu and L.W.

Bruinzeel managed to ring some geese (personal communication), which could help in a follow-up

research (Cumming et al 2011).

The visit frequency in this research was relatively low and inconsistent. When this research started

we expected that the number of geese would be approximately the same size in all measurements.

In the second measurement we found radically different numbers of geese when compared to the

first. To prevent a big gap between the results, it is important to count every day and for a longer

period of time. There were two research areas in this research. The idea of the research was to split

the two months in periods of two independent weeks, alternating between each area. Practice

turned out to be different because we were dependent of housing possibilities. Two months is

probably much too short to conduct a valid population research.

Methods of chasing the Egyptian geese

When we compare the number of Egyptian geese between PL and SR, PL has obviously the biggest

number. C. Nel, deputy general manager of SR said that four years ago there were about 400

Egyptian geese on the golf course. He tried several methods to chase the geese and not one of them

worked, with the exception of the use of dogs. Three times a day C. Nel chases the geese away with

his three border collies. Since then the amount of geese finally got lower. This approach could

explain the obvious difference in the number of geese between both resorts.

It is an asserted fact that the population of Egyptian geese continuous to increase (Lensink 1999,

Little & Sutton 2013, Magnall, Crowe 2001). For a lot of golf courses, resorts and farmers, the high

number of Egyptian geese causes real problems (Little & Sutton 2013, Magnall, Crowe 2001). The big

question is: how to handle this number of Egyptian geese and decrease the population?

To answer this question, more research is necessary. It is important to know why exactly the

Egyptian goose is doing so well. Different methods should be considered, keeping in mind that they

should be realizable on a large scale. One could think of using contraception using of deslorelinacetate implants (Petritz et al. 2013). Perhaps this would work on a small scale, but it is unknown

whether it will also have an effect on the whole population. Another possibility is the use of

Nicarbazin (NCZ). Yoder et al. (2006) proved that NCZ can be used in waterfowl to reduce the

hatchability. It can be ideal in a place where the Egyptian geese can be fed on a daily basis two weeks

before hatching. The study cited above was done with mallards. Before using NCZ on Egyptian geese,

more field studies are necessary (Yoder et al. 2006). SR would be the best research area for such a

research study because there are more couples of Egyptian geese staying in the same spot.

(Cornelissen 2013)

Chasing the Egyptian geese away from their properties has been tried several times by the managers

of PL and SR, using different methods:

Predators

Otters

Because of the crime rates in South Africa, fences surround a lot of resorts. These fences are very

useful for the Egyptian geese because the electric fence also stops predators. That is why PL released

two otters. The otters were supposed to help keep the number of Egyptian geese under control

through eating eggs. In the end the otters did not help and even disappeared (S. Mathews-Pheiffer,

personal communication, 23 August 2013).

Lifelike owl

In SR a lifelike owl was placed in a tree. In the beginning the Egyptian geese were startled but

unfortunately after a few days the Egyptian geese adapted and came back quite unconcerned (C. Nel,

personal communication 27 June 2013).

Bird of prey

Egyptian geese should be afraid of birds of prey. Acting on this knowledge the manager of PL

installed several high wooden perch in the area, which should attract birds of prey. In fact there are

two fish eagles living in the environment. However the Egyptian geese are not scared of the eagles at

all. They also brought in a falconer with no result (S. Mathews-Pheiffer, personal communication, 23

August 2013). It seems that in the field the Egyptian geese are not scared at all from birds of prey.

Dogs

In SR they chase the Egyptian geese three times each day. The deputy general manager drives with a

golf caddie and his three border collies through the golf course to chase the geese. It seems to work.

A few years ago they had about 400 Egyptian geese, right know the largest amount we counted was

about 50. It is an intensive method of chasing Egyptian geese, and it needs someone who wants to

take responsibility for the dogs, but for now it seems the only working method on the short term.

Other methods

Reflecting mirrors

In PL they tried reflecting mirrors to scare off geese, but this was not successful. McKay and Parrot

(2002) tried to find a working method to scare mute swans from grazing in fields of crops. They

studied three different deterrents like barrier tape, flags and chemical repellent. Only the high

visibility tape proved to work partially. However, this tape was used on a crop field and each strand

was suspended five centimeters from the other. If it works, it is a good possibility to use for a crop

field, but for a resort or golf course it is not an option. Children cannot play on the grass anymore,

guests cannot make their morning walks, golf cannot be played, and the scenery will severely

affected.

Wires on the roof

One of the nuisances is the noise of the Egyptian geese. In SR they attach a wire on each roof and

chimney. So they prevent the Egyptian geese from sitting on the roof and disturbing the guests. PL

struggles also with Egyptian geese on the roofs, and this method is a good idea for them too. You

don’t chase away the geese with this method, but at least relieve one of the problems they cause.

Culling

Wing shooting could in theory be helpful in managing the large numbers of Egyptian geese. The best

time for shooting is from dawn till 09:00 and from 16:00 to dusk, because then the Egyptian geese

are moving in flocks (Mangnall & Crowe 2001). The meat from the Egyptian goose is a sustainable

food source (Geldenhuys 2013). The resorts can promote shooting as a special activity with good

meat for dinner.

The methods of scaring the geese discussed above will not be successful if there is not an alternative

area nearby where the Egyptian geese could stay undisturbed (Vickery & †Summers 1992). An option

should be to make a place where they can emigrate to with a fence, so they have the same

protection against predators and green grass where the Egyptian geese don’t harm anybody.

The managers in PL and SR stated that the peak of Egyptian geese is around December and January.

The number of Egyptian geese will be doubled in comparison to June-August. It would be interesting

to do another study in that period. The recently concluded study could provide several lessons for

organizing a follow-up. One good improvement would be to take a longer period for the study, and in

just one area. Most ideal would be two research teams working in the same period spread over PL

and SR. Then one would be able to compare the results. A lot more information can be gained when

the local population of Egyptian geese can be ringed. When enough information can be collected

about the duration of the different age stages inside the population in PL and SR, stage survival and

contribution to reproduction per life stage, then the local population growth rate of Egyptian geese

can be calculated from an initial count of numbers of birds per life stage. From this, one can then

estimate how many should be culled (to diminish the population) and how different methods of

control affect the growth rate. This calculation can be done with the help of Leslie matrices (Caswell,

2000). At the moment, this information is not available for South Africa and only information from

the literature can be used, obtained in very different areas of the world. Future research could

change this.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Celia Abolnik (PHD, Associate Professor) and Prof. H.J. Bertschinger (BVSc, DrMedVet,

Dip ECAR Extraordinary Professor) for sharing their knowledge and their good supervision and

guidance in South-Africa. I am grateful to S. Williams, C. Nel and S. Mathews-Pheiffer for their

hospitality and their tireless willingness to answer our questions. I am also grateful to J. Masabane

and Leah for arranging safe and good transport every time. Last but not least, I am really grateful to

Prof. dr. ir. J.A.P. Heesterbeek (Professor of farm animal health) for sharing his experience, helping us

by being full of confidence, his goodwill, enthusiasm and valuable comments.

Referencies

Abolnik C, Gerdes GH, Sinclair M, Ganzevoort BW, Kitching JP, Burger CE, Romito M, Dreyer

M, Swanepoel S, Cumming GS, Olivier AJ (2010) Phylogenetic analysis of influenza A viruses

(H6N8, H1N8, H4N2, H9N2, H10N7) isolated from wild birds, ducks, and ostriches in South

Africa from 2007 to 2009. Avian Diseases 54:313–322

Bronwyn; The ubiquitous Egytian goose: dealing with these ‘problem’ birds.;

Thebirderonline.com; September 2013

Cumming GS, Caron A, Abolnik C, Cattoli G, Bruinzeel LW, Burger CE, Cecchettin K, Chiweshe

N, Mochotlhoane B, Mutumi GL, Ndlovu M (2011) The Ecology of Influenza A Viruses in Wild

Birds in Southern Africa. EcoHealth 8, 4–13, 2011

Geldenhuys, G., Hoffman, L.C., Muller, N. (2013) Gamebirds: A sustainable food source in

Southern Africa? Food Sec. (2013) 5:235–249

Hockey P.A.R., Dean W.R.J. & Ryan P.G.; Roberts – Birds of southern Africa, VIIth ed. The

Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town; 2005

Jensen, D., Bohmke, B., Bluewater, M., Bierlein, J. (2002) “Animal Fact Sheets – Egyptian

Goose”, http://www.zoo.org/educate/fact_sheets/savana/egoose.html. Woodland Park Zoo

Accessed September 19, 2013.

R. Lensink (1999): Aspects of the biology of Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiacus colonizing

The Netherlands, Bird Study, 46:2, 195-204

Little, R.M., Sutton, J.L.; Perception toward egyptian geese at the Steenberg golf estate, Cape

Town, south africa.; OSTRICH 84(1): 85-87; 2013

Mangnall, M.J., Crowe, T.M. (2001); Managing Egyptian geese on the croplands of the

Agulhas Plain,

Western Cape, South Africa.; South African Journal of Wildlife Research 31(1&2):

25-34; 2001

McKay, H., Parrott, D., 2002. Mute swan grazing on winter crops:

evaluation of three grazing deterrents on oilseed rape. Int. J. Pest

Manage. 48 (3), 189–194.

McLachan, G., Liversidge, R. (1940) Roberts Birds of South Africa. Cape Town: John Voelcker

Bird Book Fund.

Perlo, B., van (1999) Birds of South Africa. Italy: Harper Collins.

Petritz, O.A., Guzman, D.S-M, Paul-Murphy, J., Fecteau, K., Mete, A., Kass, P.H., Hawkins,

M.G. (2013) Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of single administration of 4.7-mg deslorelin

acetate implants on egg production and plasma sex hormones in Japanese quail (Coturnix

coturnix japonica); Am J Vet Res. 2013 Mar;74(3):490

Ramezanzadeh, B., Mohseni, M., Yari, H., Sabbaghian, S. (2009) An evaluation of an

automotive clear coat performance exposed to bird droppings under different testing

approaches. Progress in organic coatings 66-2, 149-160, 2009.

Sovon Vogelonderzoek Nederland. “Nijlgans” http://www.sovon.nl/nl/content/nijlgans ,

Accessed September 19, 2013

Sovon Vogelonderzoek Nederland. “Nijlgans Telrichtlijnen”

http://www.sovon.nl/nl/soort1700 , Accessed September 19, 2013

Yoder, C.A., Graham, J.K., † Miller, L.A., Bynum, K.S., Johnston, J.J. Goodall, M.J., (2006)

Evaluation of Nicarbazin as a Potential Waterfowl Contraceptive Using Mallards as a Model.

Poultry Science 85:1275–1284

Vickery, J.A., †Summers, R.W. (1992) Cost-effectiveness of scaring brent geese Branta b.

bernicla from fields of arable crops by a human bird scarer. Crop protection: vol. 11 October

1992