Ask A Vet: Don`t Let Your Horses Be Strangled

advertisement

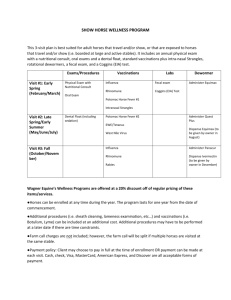

Ask A Vet: Don’t Let Your Horses Be Strangled! Sunday, November 21, 2010 Dear Dr. Weldy’s, Our neighbor has told us that his horses have come down with strangles. What should I be looking for and how can I protect my own horses? Dear Reader, “Strangles” is a common term for an upper respiratory infection that causes swelling under the jaw of horses. It is highly contagious in horse populations, but not in people. Strangles is caused by the bacterium Streptococcus equi and typically infects the lymph nodes of the head and neck. The most common symptom of infection is swelling and abscessation under the jaw. Other symptoms might include fever (rectal temperature over 101.5◦F), thick nasal discharge, depression, and difficulty swallowing. Some horses may develop a noise when breathing which is caused by swollen lymph nodes located next to the larynx and trachea. These animals exhibit respiratory distress and may extend their head and neck in order to breath more easily. This is, in fact, where the term “strangles” came from as they seem to be strangled from within. Eventually, abscessed lymph nodes rupture and drain thick pus, especially from the submandibular nodes under the jaw line. Any lymph node may become infected however, and may break and drain including lymph nodes outside of the head and neck. This condition is called “Bastard Strangles” and indicates an increase in the severity and spread of the infection throughout the body. Strangles abscesses have been found in the lungs, abdomen, joints, spinal cord, brain, and throughout the skin. Because of the unique nature of the disease, diagnosis is usually pretty straight forward. A few horses can develop the fever and nasal discharge without the swollen jaw line. These are hard to differentiate from a viral upper respiratory infection and may require a culture swab of the nose to determine the cause. Another diagnostic challenge is the asymptomatic carrier horse which does not rid itself completely of the bacteria, but sheds the disease intermittently for weeks to months causing recurring strangles cases in the same barn. These carriers also infect new horses which do not have immunity against strangles. Culture and/or PCR testing of nasopharyngeal washes may help identify carrier horses. The treatment of strangles in routine cases involves administering flunixin meglumine (Banamine) or Bute and hot packing the swollen lymph nodes. Injections of B vitamins to stimulate appetite may also be used. This supportive care is sufficient for most cases of strangles. The use of antibiotics is typically limited to the severe or complicated cases such as “bastard strangles” or those in which the horse is much sicker than is normal. If antibiotics are used, prolonged courses are called for. If in doubt, please call your veterinarian for an accurate diagnosis and advice. The inappropriate use of antibiotics can prolong the disease or even cause the bacteria to move deeper into the lymph node chain, i.e. “bastard strangles”. If you are unlucky enough to experience an outbreak, the first thing to do is stop the movement of animals into and out of the farm. Isolate the affected horses if possible at the first sign of fever. Strangles can be transmitted within 48 hours of the onset of fever. Always feed or handle the healthy horses first and use separate water and feed buckets for the sick horses. People and equipment can transfer the infection from horse to horse. Washing hands and disinfection can be very effective. Diluted bleach at a 1:10 ratio is an adequate disinfectant. Prevention of strangles can be achieved via avoidance and vaccination. Common sense tells us that avoiding farms and horses known to have strangles goes a long way. Vaccination can give your farm another layer of protection. Strangles vaccine is available in injectable and intranasal forms. Which form you use should be discussed with your veterinarian. Vaccination is only recommended for healthy horses with no fever or nasal discharge. Horses that travel routinely or are exposed to varied horse populations should be considered for vaccination. The first time you vaccinate your horse, a second booster dose should be given three to six weeks later. Peak immunity is reached within two weeks of the booster. -Dr. Wade Hammond