Complicated Strangles: two cse reports and a literature review

advertisement

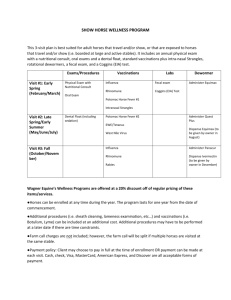

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE COMPLICATED STRANGLES: TWO CASE REPORTS AND A LITERATURE REVIEW Vol. 58 (4) 2003 A. Kol1, O. Levi1, D. Elad2 and A. Steinman1 1. Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, P.O.B. 12, 76100 Israel. 2. Dept. of Bacteriology, Kimron Veterinary Institute, P.O.B. 12, 50250 Bet Dagan, Israel Abstract Streptococcus equi subsp. equi infection, commonly known as "strangles” is characterized b nasal discharge that is eventually followed by abscessation of the lymph nodes of the head an Morbidity is nearly 100% in susceptible populations while the mortality rate ranges from 0 to 10 due to complications. We describe a severe case of S. equi lung abscessation and a case of mesenteric abscess fillies. The two cases represent complicated cases seen during a large-scale outbreak that occ Israel in 2002. The antibiotic susceptibility tests of 7 isolates of the microorganism carried out i during this outbreak are presented and the recent literature on S. equi subsp. equi infection rev Introduction Streptococcus equi subsp. equi, a gram-positive bacterium, is the causative agent of strangles. Two of the major virulence factors associated with infection are the hyaluronic acid capsule and the surface antigen M protein, which are antiphagocytic (2). S. equi subsp. equi adheres to the epithelial cells of the buccal and nasal mucosa of the horse (1). Following adherence, S. equi subsp. equi attaches to the cells on the tonsillar crypts and the ventral surface of the soft palate and can be detected in the mandibular or retropharyngeal lymph nodes several hours after infection. The organism slowly multiplies extracellulary and attracts a large number of neutrophils (3). S. equi subsp. equi is not a normal inhabitant of the equine upper respiratory tract and does not require prior viral infection for successful colonization and infection (1). Although strangles can occur in horses of any age, those less than one year old were most commonly affected (4) and morbidity is nearly 100% in susceptible populations. The incubation period is between 2 and 6 days. The common clinical signs include a febrile, serous nasal discharge that later becomes mucopurulent, and evidence of intermandibular and/or retropharyngeal lymphadenopathy. Lymph nodes are initially firm but become fluctuant before rupturing at 7 to 10 days after the onset of clinical signs. The average duration for the disease is 23 days (1). A complication rate of up to 20% has been reported, with a mortality rate as high as 40% of the complicated cases (3). The potential complications of S. equi subsp. equi infection include internal abscessation, purpura hemorrhagica, guttural pouch empyema, suppurative necrotic bronchopneumonia, myocarditis with endocarditis, and laryngeal hemiplegia (1,2,3). The most common complication is internal abscessation, often referred toas “ bastard strangles”. The main locations of abscesses include the lung, mesentery, liver, spleen, kidneys, and brain (3). The causes of internal abscessation are not known, although inadequate antimicrobial therapy during respiratory catarrh and lymphoid abscessation may be contributory (2). Strangles has been diagnosed in Israel for many years either in a sporadic form or as localized outbreaks. During 2002 a large-scale outbreak affecting hundreds of horses all over Israel was reported (personal communication, Haik R., Avni G.). This outbreak renewed the debate regarding treatment and preventive measures that should be taken to reduce the spread of the disease. Most cases recovered uneventfully during the 2002 outbreak. However, several horses died due to complications (personal communication, Haik R., Avni G.). We describe in detail two cases of "bastard strangles" referred to the Koret School of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Teaching Hospital (KSVM-VTH). Case 1 A one-year-old filly pony was referred to the KSVM-VTH with the chief complaint of severe dyspnea. One month prior to admission, many of the horses on the farm including the filly, suffered from an undiagnosed upper airway disease. All other horses recovered uneventfully. The filly subsequently became weak and slightly dyspneic. The owner treated her with intramuscularly procaine penicillin for several days. On arrival, physical examination revealed cachexia, depression and mild dehydration. The filly showed severe dyspnea with a purulent bilateral nasal discharge. Wheezes and crackles were auscultated on the left thorax caudal to the heart. Radiology revealed (lateral view), caudally to the heart, a large (18cmX10cm) egg shaped mass, with a straight horizontal line (fluid level) between radiolucent (gas) and radiopaque (fluid/soft tissue) medium (fig. 1). An ultrasound-guided aspiration from the mass yielded a flocculent turbid cream-colored fluid that contained white flakes. Cytology of the aspirated fluid showed numerous degenerated and disintegrated neutrophils with nuclear striking and a small number of reactive macrophages showing phagocytosis of neutrophils and debris. These findings led to a diagnosis of an abscess. Complete blood count revealed elevated white blood cells (WBC) of 25* 1000/µl (normal 5.4-14.3 *1000/µl) and elevated triglyceride (Trg) - 392 mg/dl (normal 5.3-54 gr/dl). S. equi subsp. equi, identified with the APIStrep kit (bioMerieux, France), was cultured from the aspirated fluid. Antibacterial susceptibility was determined by a standardized disc susceptibility method (NCCLS). The owner refused our recommendation for surgical treatment and he treated the pony with procaine penicillin (25,000 iu/kg bwt IM bid), to which the isolate was found to be susceptible (Table 1). A week later the owner reported that the filly died. Necropsy was not carried out. Fig 1: Chest X-Ray, lateral view, case 1 Table 1: Susceptibility of the S. equi subsp. equi isolated in those cases in comparison to other isolations in Israel during n 2002.Drug Isol ate 1 Isol ate 2 Isol ate 3 Isol ate 4 Isol ate 5 Isol ate 6 Isol ate 7 Penicillin S S I S S I I Ampicillin I S I S I I S Oxacillin S S S S S S Cephalothi S S S S S S S S S S S S S S Erythromy S I S I S I S Clindamyc I S I S I S Sulfadiazi I S S R I S S Tetracycli S S I S S S S Neomycin S S S S S S R Gentamici S S S S S S S Ciprofloxa cine I S I S S S S Amoxicilli n/ clavulanic. a.* cin in ne/ Trimethop rim ne* n R: resistant, I: intermediate, S: susceptible Isolate 1 - case 1 Isolate 2 - case 2 *- Not recommended for use in horses (13) Case 2 A 15 month old Arabian filly was refered to the KSVM-VTH with the complaint of abdominal mass that was palpated per rectum. The filly had undergone medical treatment for intermittent mild colic for a week prior to admission. Two months before referral, a strangles outbreak occurred at the home farm of the filly. At the time of the outbreak the filly had fever and nasal discharge, she was treated with procaine penicillin (13,000 iu/Kg IM, bid) for ten days. Following treatment the filly’s condition improved. On arrival, physical examination revealed a bright and alert filly with no abnormalities. On rectal examination a round firm mass with irregular surface (25 cm diameter) was palpated connected with a pedicel to the mesentery. Trans-rectal ultrasonography showed a fluid filled mass with compartments with no peristalsis nor gas. A complete blood count revealed elevated WBC- 25.43* 103/µl, slight anemia (microcytic anemia), low hemoglobin (Hgb)- 7.6 gr/dl (normal 11-19 gr/dl) with mild elevation in total solids (Ts)- 8.4 gr/dl (normal 5.7-7.9 gr/dl) and Globulin (Glb)- 5.2 gr/dl. A peritoneal fluid sample was hazy yellow with a high cell count (WBC19.7*103/µl) and high Ts (3.6 gr/dl). In an exploratory laparotomy, an abscess was found connected by a pedicel to the mesentery of the jejunum. The abscess was not dissected because of the proximity to large blood vessels and was therefore drained. A Foley catheter was placed from the lumen of the abscess to the outside through the ventral body wall. A second Foley catheter was placed from the peritoneal cavity to the outside through the ventral body wall. During surgery a fluid sample was aspirated from the abscess. S. equi subsp. equi, identified with the APIStrep kit (bioMerieux, France), was cultured from the aspirated fluid. Antibacterial susceptibility was determined by NCCLS. Post-operatively the abdomen was flushed once (using 10 liters of saline) and the peritoneal Foley catheter removed. The abscess was flushed for five days (twice a day) using 2% povidone iodine solution, and the Foley catheter removed when clean fluid was flushed out of the abscess twice. Medical treatment included flunixin meglumine (0.5-1 mg/kg I.V bid) for five days, gentamicin (6.6 mg/kg I.V sid), penicillin G (40,000 iu/kg I.V qid) until discharge (10 days) and procaine penicillin (20,000 iu/kg I.M bid) for another ten days. Trans rectal ultrasonography before discharge revealed a marked decrease in the mass diameter (10 cm). On discharge the filly was bright and alert and did not show signs of colic but the WBC remained elevated (14.5*103/µl). Three weeks later the WBC was within normal limits (7.5*103/?l). Discussion As early as 1664, Solleysel, concerned about the contagious nature of strangles, recommended isolation of affected animals and pointed out that the commonest source of infection for horses was water buckets (3). Persistence in affected herds may be due to survival of S. equi subsp. equi either in carrier hosts or in the environment. Recent epidemiological investigation by Newton et al in 1999, provide further evidence that a carrier state can be responsible for the persistence of S. equi subsp. equi between outbreaks. In these cases the guttural pouches were found to be the sites of carriage and the mean duration of carriage was 19 months (5). Both cases have the same characteristics and they fit the literature, the only difference is the method of treatment and the final outcome. Fillies with “bastard strangles,” that was diagnosed after an inadequate antimicrobial therapy, is described in both cases. They suffered from a large internal abscess that interrupted the function of an adjacent organ, and they both had elevated WBC. The filly that underwent surgical treatment followed by an aggressive medical treatment survived in contrast to the second filly that was treated medically and died. S. equi subsp. equi infection is a very contagious disease, therefore proper treatment and measures for preventing the spread of the disease are important. Although it is a well known disease there is a debate and uncertainty regarding its treatment. It is generally agreed that treatment is a function of the stage of the disease, of both the individual horse and the whole stable. How to treat the individual horse? 1. Horses with early signs of strangles (including pyrexia and depression, without abscessation of the lymph nodes) should be isolated. The disease can be arrested at this time with antimicrobial treatment. The drug of choice is penicillin (procaine penicillin 22,000 iu/kg IM bid, for 5 days after complete resolution of clinical signs) (6), but according to the tests carried out in the Department of bacteriology, Kimron Veterinary Institute, S. equi subsp. equi was susceptible also to oxacillin, cephalothin and gentamicin (table 1). However, there is a high probability of relapse following cessation of therapy, because protective immune responses are poor in antimicrobially treated horses (3). Inadequate antimicrobial therapy may be contributory to the formation of “bastard strangles”. 2. Horses with lymph nodes abscessation. Therapy should be directed toward enhancing maturation and drainage of the abscess (3). The administration of antimicrobial medication may slow down the progres of the abscessation and is generally contraindicated. In contrast, a recent study showed that IM administration of 20,000 iu/Kg of procaine penicillin G given every 24 h for 21 days eliminated Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus from an abscess model (tissue chambers) in seven out of eight ponies (7). When an abscess is draining, it should be flushed regularly with a 2-5% povidone-iodine solution (6). 3. Horses exposed to strangles - Antimicrobial therapy can prevent an exposed horse or foal from contracting strangles during the period of therapy (1,3). Penicillin therapy (procaine penicillin 22,000 iu/kg IM bid) may be effective if exposure to the organism can be ceased before the end of therapy. 4. Horses with a complication - These horses should be treated immediately aggressively and specifically, including surgical procedures (4). How to control an outbreak? Healthy carriers of S. equi subsp. equi have long been regarded as a problematic source of “strangles” in susceptible animals(8). The predominant sites of carriage are the guttural pouches (9). The first control measure for arresting the spread of the disease is to prevent movement of horses between farms and to isolate all clinical cases and healthy carriers. Flies may serve as mechanical vectors and efforts to control the fly population should be made during an outbreak. An asymptomatic carrier is defined as one from which S. equi subsp. equi is cultured from at least one of three weekly nasopharyngeal swabs and the animal has no clinical signs of strangles (5). All asymptomatic carriers were found to have lesions in their guttural pouches including empyema and chondroids (9). The mean duration of carriage was 19 months (5). For early identification of clinical cases the rectal temperature is measured once or twice daily. In infected stables, any elevation of rectal temperature is suggestive of a S. equi subsp. equi infection. S. equi subsp. equi can be demonstrated by culture or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of nasal swabs or guttural pouch aspirations. Elimination of guttural pouch infection in asymptomatic carriers can be achieved by alleviating the inflammatory pathology by flushing the guttural pouches, combined with systemic and topical use of an antibiotic (8). Surgery is recommended in cases in which both pharyngeal openings of the guttural pouches are occluded or in cases in which medical treatment was not satisfactory. Vaccination Most vaccines available incorporate inactivated whole cells or M-protein extract (10) and adverse reactions were seen after their administration. Local reactions of firm edematous swellings account for 72% of the reported cases, while systemic signs of arthritis, stiffness, lameness, founder and lethargy were described in 24%. Fever, respiratory signs, colic, ataxia and edema of ventral abdomen and lower legs are less frequent. Purpura haemorrhagica was reported after use of a whole cell vaccine (11). The prevalence of an adverse reaction has not been clearly established, but it can be as high as 5% (12). Immunity is obtained in less than half of the vaccinated animals, and then only when the components were incorporated in an adjuvant or when multiple injections were given (2). Following recovery from an outbreak of strangles, approximately 75% of the infected animals have an extended period of resistance to re-infection. Moreover, there is evidence that for protection, a mucosal immune response rather than a systemic one is needed (10). One study showed that a live attenuated S. equi subsp. equi vaccination administered in the sub-mucosa (of the upper lip) appeared to be efficacious with a side effect of a transient reaction at the site of injection (10). It seems that we will have to wait for better and safer vaccines. LINKS TO OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS ISSUE References 1. Dorothy, M. A. and David, S. B.: Respiratory system. In: Reed, S. M. and Bayly, W. M. (Eds.): Equine internal medicine. Saunders W.B., Company, Philadelphia, pp. 62-64, 1998. 2. Dorothy, M. A. and David, S. B.: Respiratory system. In: Reed, S. M. and Bayly, W. M. (Eds.): Equine internal medicine. Saunders W.B. Company, Philadelphia, pp. 266-267, 1998. 3. Sweeny, C. R.: Streptococcus equi infection (strangles). In: Smith, B. P. (Ed.): Large animal internal medicine. Mosby, Philadelphia, pp. 504-507, 2002. 4. Golland, L. C., Hodgson, D. R., Davis, R. E., Rawlinson, R. J., Collins, M. B., McClintock, S. A. and Hutchins, D. R.: Retropharyngeal lymph node infection in horses: 46 cases (19771992). Austral. Vet. J. 72: 161-164, 1995. 5. Newton, J. R., Verheyen, K., Talbot, N. C., Timoney, J. F. Wood, J. L. N., Lakhani, K. H. and Chanter, N.: Control of strangles outbreaks by isolation of guttural pouch carriers identified using PCR and culture of Streptococcus equi. Equine vet. J. 32: 515-526, 2000. 6. Bonnie, R.: "How do I control a strangles outbreak in my training barn?". Compend. Contin. Educ. Pract. Vet. 20 (7): 844-845, 1998. 7. Ensink, J. M., Meijer, L. A. and Van Duijkern, E.: Clinical efficacy of trimethoprim/sulfadiazine and procaine penicillin G in a Streptococcus zooepidemicus infection model in ponies. International conference on antimicrobial agent in veterinary medicine (AAVM). Helsinki Finland, pp. 48, 2002. 8. Verheyen, K., Newton, J. R., Talbot, N. C., De Brauwere, M. N. and Chanter, N.: Elimination of guttural pouch infection and inflammation in asymptomatic carriers of Streptococcus equi. Equine vet. J. 32: 527-532, 2000. 9. Fintal, C., Dixon, P. M., Brazil, T. J., Pirie, R. S. and McGorum, B. C.: Endoscopic and bacteriological findings in a chronic outbreak of strangles. Vet. Rec. 147: 480-484, 2000. 10. Jacobs, A. A. C., Goovaerts, D., Nuijten, P. J. M., Theelen, R. P. H., Harford, O. M. and Foster, T. J.: Investigation towards an efficacious and safe strangles vaccine: submucosal vaccination with a live attenuated Streptococcus equi. Vet. Rec. 147: 563-567, 2000. 11. Smith, H.: Reaction to strangles vaccination. Aust. Vet. J. 71(8): 257-258, 1994. 12. Sezun, G. S.: Correspondence to: Reaction to strangles vaccination. Aust. Vet. J. 72(12): 480, 1995. 13. Plumb, D. C. (Ed): Veterinary drug handbook. Pharma Vet Publishing, Minnesota, pp. 36-38, 475-479, 597-600, 1999.