Master Thesis...position - Lund University Publications

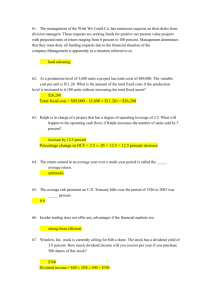

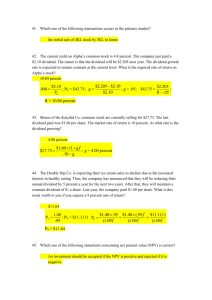

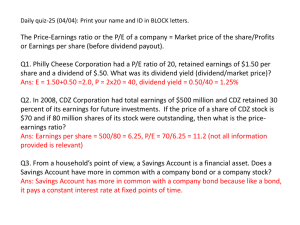

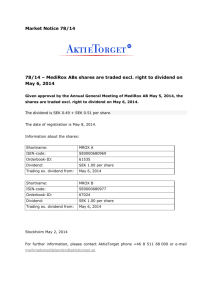

advertisement