Swarming Up A Storm: Why Animals School And Flock Nell

advertisement

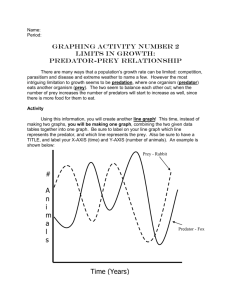

Swarming Up A Storm: Why Animals School And Flock Nell Greenfield Boyce August 17, 2012 2:57 AM ET By tricking live fish into attacking computergenerated "prey," scientists have learned that animals like birds and fish may have evolved to swarm together to protect themselves from the threat of predators. "What we're doing here is we're getting predatory fish to play a video game," says Iain Couzin A school of Blue Tang fish swimming together off the Caribbean island of Bonaire. It has long been assumed that the schooling behavior of fish evolved in part to protect animals from being attacked by predators. "And through playing that game, through David J. Phillip/AP seeing which virtual prey items they attack, we can get a understanding of how behavioral interactions among prey affect their survival." 1. What was the purpose of this experiment? It has long been assumed that the schooling behavior of fish and the flocking behavior of birds evolved in part because it helps protect individuals from being attacked by predators, says Couzin. "But in actual fact there is surprisingly little direct evidence." That's because it's been hard to come up with experiments that could test how different kinds of group behavior affect predation risk. "It is very hard to manipulate the behavior of, say, a bird flock and then see what effect it has on a falcon. That's virtually impossible," says Christos Ioannou at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. Together with colleague Vishwesha Guttal, they decided to see if they could create a virtual population of pretend fish that would look convincingly real to a predator. 2. What was difficult about experiments that test group behavior? The predator they selected was the bluegill sunfish. They went to a local lake with nets, collected a bunch of them, and took the fish back to the lab. "The nice thing about bluegill sunfish is they're generalist predators. They will tend to hunt pretty much anything that's alive and in the environment that's smaller than them," says Couzin. "And so we don't need to train them to attack our virtual prey." 3. Why did the researchers decide to study bluegill sunfish? Adapted from http://www.npr.org/2012/08/17/158931963/swarming-up-a-storm-why-animalsschool-and-flock The prey were little dots of light projected onto a film on the inside of the tank. "To the fish the little dots look very much like little zooplankton, that the fish like to eat. The predatory fish would hover near a dot, and then strike — only to get a mouthful of nothing. 4. What “prey” did the researchers use? The computer-generated prey items were programmed to do different behaviors. For example, some wanted to group together, others would be alone, and still others would follow the dots that were next to them. 5. What 3 behaviors were the “prey” programmed to do? The researchers kept track of which individuals got attacked, and programmed the system so that those individuals' behaviors were less likely to be present in the next generation of prey. "And so we could actually allow our virtual population to evolve the strategies that best avoid being attacked by real predators," says Couzin. What they learned is that in response to the attacks, the virtual prey spontaneously formed groups that move together. "I think it's the first evidence that this schooling and flocking behavior we see in bird flocks and fish schools, has an anti-predatory effect." 6. What did the researchers learn from this experiment? 7. How does schooling increase an organism’s fitness? Adapted from http://www.npr.org/2012/08/17/158931963/swarming-up-a-storm-why-animalsschool-and-flock