Professional Connect 2014 Science Q&A (MS

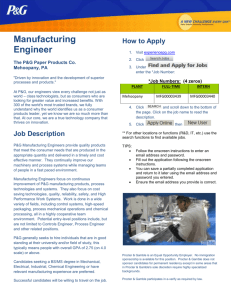

advertisement

Professional Connect: Science Q&A – 8 May 2014 Written by student writer, Danny Ranson Chair: Janice Simpson: Senior Careers Advisor, University of York Panellists: Dean Cook: Head of Science Strategy, FERA Tom Pagett: Biodiversity Officer, Environment Agency Neil Powell: AED Associate, Cold & Flu, Reckitt Benckiser Emma Ramsey: Products Research Scientist, Procter & Gamble Dr Tomas Stanton: Senior Scientific Officer, Home Office Dr Fiona Taylor: Feedstock Development Unit Technologist, Biorenewables Development Centre (BDC) Panel Q & A: 1. How did you begin your careers? Most of the panel members graduated in a science subject. Some then went on to join companies where they had previously done work experience, either as a graduate or during a year in industry as part of the degree, others gained their first jobs as a result of applying to temporary or permanent roles. Dean Cook (FERA) was an exception, having begun his career after A-levels and working up from a basic position, only going to university some years later. 2. What is the work culture like within your organisations? The panel generally agreed that the work culture for a scientific professional is fairly relaxed; casual clothing including jeans and trainers is often acceptable, along with flexible hours, provided that the work gets done. Emma Ramsey (Procter & Gamble) generally works eight hours between 7.30 and 21.30, and can choose when those eight hours fall. For some members of the panel work hours are slightly more regimented, but finishing early on a Friday, for example, is quite normal. Dr Tomas Stanton (Home Office) added that for those in the Civil Service, based in London, more formal clothing and hours are likely to be the norm. Dean (FERA) warned that because mobile phones and computers now allow constant communication, he and some of his colleagues can find it difficult to switch off from work beyond the regular working day. 3. In each of your roles, what percentage of time do you spend actually ‘doing science’? The great variety of responses this time illustrates the wide potential of careers in science. Neil Powell (Reckitt Benckiser) stood out as he spends a lot of time working to improve analytical instrumentation, but the more common response from the panel was that actual science or lab work was only part of their job, though more common upon first joining a company (some of the members of the panel try to create opportunities to work in the lab as they miss it!). Emma’s (Procter & Gamble) work emphasises the consumer of the product as much as, or more than, the product itself, while Dean (FERA), Tom Pagett (Environment Agency) and Dr Stanton (Home Office) are occupied more with management than research. Dr Fiona Taylor (BDC) said her work was a 50- 50 mix but emphasis was on the managerial side as her career progressed. However, it was clear that in general there is flexibility within and across work roles and students need to consider this when choosing career paths. 4. How important is a placement year as opposed to a straightforward degree? There was a unifying response that a degree on its own is insufficient to begin a successful career in science. However, it was emphasised by some panel members, especially Dean (FERA) and Emma (Procter & Gamble), that it is possible to be imaginative in developing vital extra experience outside of a placement year. Transferable skills such as leadership are important - these may have been developed in a context quite different from the work of a science professional but are often still valid. Work experience is perhaps the most useful means to develop such skills, but the panel agreed that even this need not be in a science role. However, Neil (Reckitt Benckiser) and Emma (Procter & Gamble) were both offered jobs with the company where they did a year in industry, while Dr Taylor (BDC) found her placement at an agricultural institute very useful. It was generally agreed that gaining knowledge specific to a company is very desirable, whether that be through a placement or through general work experience. Indeed, such experience may override a degree, as in the case of Dean (FERA) who developed his career immediately after A-levels. 5. How can I get work experience which could help me to get an industrial placement? It was agreed that most science - specific work experience with larger companies is reserved for penultimate year students. Responses drew heavily on those to the previous question; students should widen their perception of what counts as experience and consider volunteering or part-time work as well as a formal industrial placement. Emma (Procter & Gamble) summed up the thoughts of the panel in saying that if work experience is not freely available, you should look to gain life experience instead. Tom (Environment Agency) added that it is generally easier to contact and arrange work experience with smaller organisations, unlike the Civil Service whose bureaucracy tends to impede such communication. Although there is no clear consensus, the importance of eventually getting specific work experience was emphasised this time by Peter Chapman (Director of Regulatory Affairs, JSC International), a networker, who said that a placement is vital for getting into a good science career. 6. Is it possible to go into a science career as a non-science graduate, and if so, how? This question revealed the variety of entry routes into the science professions, touching on how to maximise your chances. The answer to the question was a resounding yes. Emma (Procter & Gamble) stressed the importance of transferable skills over subject-specific knowledge, adding that her work only requires her to have quite basic scientific knowledge. Furthermore, Dean (FERA) stressed that it is becoming increasingly important to combine science with other disciplines, especially social sciences – adding that he began his career with only A-levels in History, Geography and Business studies. At this point, networker Zoe Pattison (Flood Risk Management Officer, Environment Agency) added that communication and interpersonal skills are highly valued, which scientists sometimes struggle to demonstrate. Communications and marketing roles in scientific organisations were often those which non-scientists could access, particularly if they could show interest in scientific issues through volunteering or work experience. Dr Stanton (Home Office) pointed out that many scientific roles will require a science degree because of their specialist nature. Masters study was suggested as a means of standing out from the crowd, regardless of undergraduate degree, with a PhD giving you an even greater chance of entering a science job at a high level. 7. How much freedom do you have to choose your research/tasks? While answers varied, the general response was that panel members have a good level of flexibility in their work. Neil’s (Reckitt & Benckiser) work falls in the later stages of a project, so although he might choose how to complete it, he does not choose the project itself. Tom Pagett (Environment Agency) and Dr Stanton (Home Office), both of whom work for the Civil Service, agreed that the important thing is to get a foot in the door; once inside the organisation there is more flexibility and a wider range of opportunities than are made available externally. Dr Stanton also mentioned an innovation fund which can offer up to around £5000 for worthwhile projects, and Dean (FERA) stressed the importance of being able to sell yourself and your idea in order to make the most of such opportunities. 8. At what point did you know what career you wanted to do? The consensus from the panel was that it is not necessary to have a fixed career plan from the outset, but rather to keep an open mind and learn as you go along. Dean (FERA) and Tom (Environment Agency) agreed that control over your work increases as your career path progresses, so that you should not expect it straightaway. However, as a side point Dean (FERA) added that those looking to get into the science sector could try to predict what scientific knowledge and priorities will be valued in five to ten years’ time, thereby preparing ahead of time, by researching and understanding government priorities. He also emphasised that students should make the most of social and networking opportunities – with each other as well as with professionals – as these connections may become very valuable in the future. 9. What are your top tips for students seeking a career in science? Emma Ramsey (Procter & Gamble): Know your skills and how to market them. Neil Powell (Reckitt & Benckiser): Gain work experience - a year in industry if you can. Tom Pagett (Environment Agency): Say yes: be open-minded and try out a variety of work as you can’t always predict where you’ll end up. Dr Tomas Stanton (Home Office): There’s no need to focus your work early. Diversify first.