EDUCATION - Thomas Starr King Middle School

advertisement

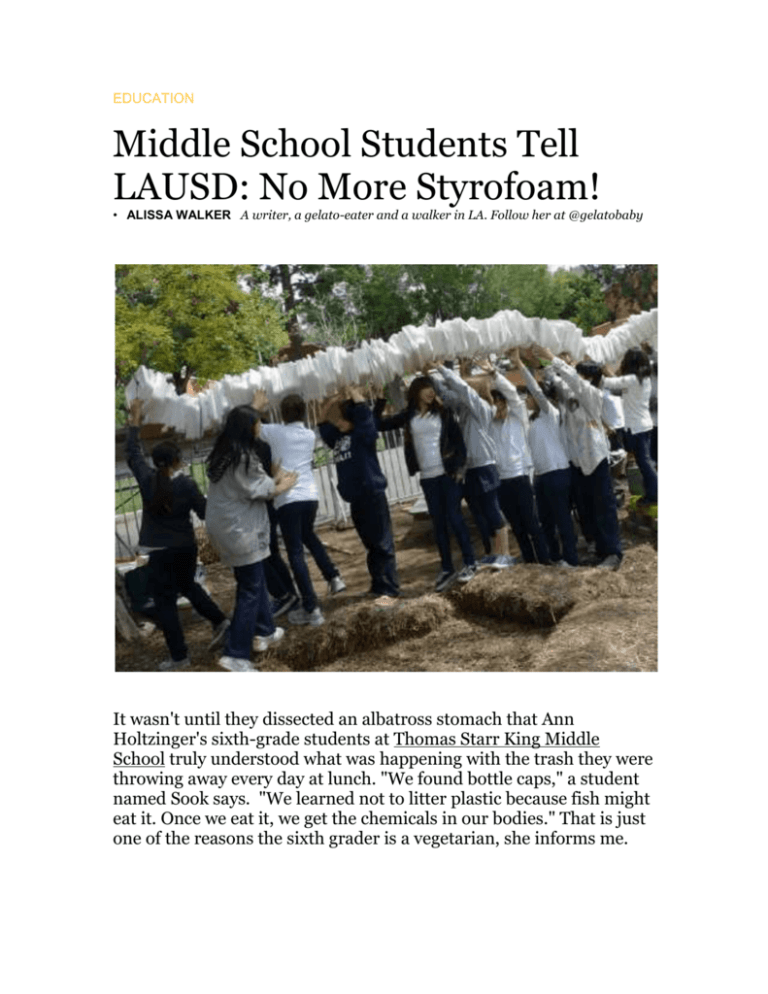

EDUCATION Middle School Students Tell LAUSD: No More Styrofoam! • ALISSA WALKER A writer, a gelato-eater and a walker in LA. Follow her at @gelatobaby It wasn't until they dissected an albatross stomach that Ann Holtzinger's sixth-grade students at Thomas Starr King Middle School truly understood what was happening with the trash they were throwing away every day at lunch. "We found bottle caps," a student named Sook says. "We learned not to litter plastic because fish might eat it. Once we eat it, we get the chemicals in our bodies." That is just one of the reasons the sixth grader is a vegetarian, she informs me. The lesson in ocean-bound plastic was a transformative moment for most of the class at the Los Angeles school. "Everyone's concerned about how it's affecting animals like seagulls and sea animals," Marisol tells me. "We want to show how you can make a difference by volunteering or doing service." In their case, making a difference meant collecting the used Styrofoam trays from their cafeteria and stringing them up into 30-foot art installation in the center of campus that they hoped would get their school's—and their district's— attention. The project is part of the curriculum at Farm King, the school's garden, where Holtzinger's students go every Tuesday for duties like harvesting cavolo nero kale and calculating the number of worms in a square foot of soil. Volunteer and garden manager Brian Miller, who runs a photography company when he's not elbow deep in compost, came up with the concept because he wanted to give ecology studies some real-world relevancy. "These students will be putting lessons into direct action," he says. After carrying their trash around for a week, the students visited the Burbank Recycling Center, where they uncovered a horrific truth about one of the most prevalent materials in their school: Styrofoam. "They don't even recycle it!" a group of students answer in unison when I ask what's so bad about it. "They don't collect it because it turns into little bits," says Miya. The students began camping out at the recycle bins after lunch to intercept the Styrofoam trays, which they cleaned, brought to the garden, and began stringing onto a rope, like a giant white necklace. The garden itself is positioned in the center of the school, so their highly-visible, large-scale craft project has been noticed by all students (and teachers) as they change classes. But to reinforce their message, the children spent weeks designing and painting signs to encourage their fellow 2,000 students to monitor their own waste. "Plastic is not fantastic!" one of the signs scolds. Over the weeks, the Styrofoam creature grew, soon snaking through the beds of broccoli and sweet peas that kids eat eagerly right off the vines. And last Tuesday (aided by adults), the students looped a rope over one of the tallest branches of the giant acacia tree that shades part of the garden and hoisted it 30 feet into the air. As it hung between the leaves like an awkward wind chime, the students gawked at their creation. The final count for the tower is a jaw-dropping 1,260 trays, which, Miller reminds the students, is less than the 1,400 trays that are thrown away at the school each day. For perspective, LAUSD operates about 730 schools. But the triumphant tower wasn't all that Miller had planned for the students. As they stood in a circle, snapping photos of their styrocreation with their own cell phones, he presented them with another gift: brightly colored, reusable plastic trays. "How many of you would use this instead of a Styrofoam tray?" he asked. Their eyes lit up and their hands shot into the air. "Yeah!" they cheered. "Me!" Believe it: sixth graders, jumping up and down, shrieking with enthusiasm over a reusable lunch tray. You would have thought it was autographed by Justin Bieber. It's not a perfect tray, Miller acknowledged, in that it's still plastic. But it would make this class leaders within the school, allowing them to tell the story to their fellow students about why they don't use Styrofoam trays. "It's their own choice," he said. "They have the experience and knowledge now, and we empowered them to make a change."