Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement

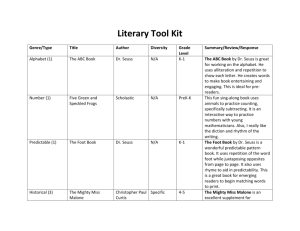

Hackeng Fairy Tale Structures, Social Input and Cultural Guidance: a Psychonarratological Analysis of Cohesive Influences on Children’s Cognitive Development ABSTRACT The purpose of this essay is to examine how cognitive development in children is stimulated by their encounter with fairy tales, and which factors that are related to the reading of fairy tales may influence this interaction between the psyche and literature. To this end the cognitive development theory by psychologist Jean Piaget is described and components from the developmental stages he distinguishes are singled out and linked to the structure of fairy tales as Propp theorises. Additionally, the cultural and social factors that determine which fairy tales are encountered and how children’s reception of fairy tales can be altered are briefly outlined in an effort to demonstrate how multiple disciplines interact to establish an impact on cognitive development. Name: Sanne Hackeng Student number: 3810194 Supervisor: S.J. Cook Word count: 9535 excluding works cited Bachelor thesis English Language and Culture, Creative Writing 1 Hackeng Content 0 Introduction 3-5 Chapter 1 Cognitive Development 6-11 Chapter 2 Narrative Theory 12-19 Chapter 3 Elements of the fairy tale 20-30 Chapter 4 3.1 “Cinderella” 21-22 3.2 “The Wolf and Seven Goats” 23-24 3.3 “Snow white” 25-26 3.4 “Little Red Riding Hood” 27 3.5 “Sleeping Beauty” 28 3.6 “Hänsel and Gretel” 29-30 Conclusion 31-35 Works Cited 36-38 Appendix 39 Vladimir Propp’s functions 40 The Grimms’ fairy tales 41 2 Hackeng 3 Introduction Many developmental psychologists have aimed to describe and explain developmental change and develop a theory that could make predictions about this change that could be scientifically validated (Leman, Bremner, Parke & Gauvain 12). Theories of human development have ranged from behaviorist and maturational approaches to psychodynamic and cognitive approaches (Leman et al. 12-20). When it became evident that the behaviorist approach to human development could not explain phenomena such as creative learning, psychologists turned to the cognitive approach, which was advocated by psychologist Jean Piaget (Leman et al. 20). Piaget’s cognitive development theory provides an extensive contemplation of children’s development, especially when it is considered in the context of children’s literature. The link between the books children are most often presented with, children’s books, and their cognitive influences on them seems to have been researched with regard to the influence of violence on children through media (Drabman & Thomas 418-421) and the notion of gender roles in children’s books and how they affect children’s conceptions of the world (Peterson & Lach 185-197). In light of this link, the current essay will not merely consider the influence of themes and content of children’s books but will explore the possibilities of a deeper connection between child and literature within the framework of fairy tales. The theory of psychonarratology expresses this connection, a field that approaches the study of literary response through a framework of psychological focus: “Psychonarratology is … the investigation of mental processes and representations corresponding to the textual features and structures of narrative” (Bortolussi et al. 24). This method requires a coherent corpus of children’s books to be delineated. The idea of the universality of children’s development, occurring regardless of culture and place Hackeng 4 (though not unaffected by either), has led to the consideration a universal children’s book genre: the fairy tale. Many heuristics have been applied to fairy tales regarding their effects on young minds, such as their archetypal effects as outlined by Carl Jung (qtd. in von Franz 1), or their effects on the development of the id and ego as maintained by Bettelheim (6). However, these theories focus on how very specific aspects of children’s minds are affected by fairy tales. The comprehensive cognitive development theory by psychologist Piaget may provide for a more complete image of these effects on children due to its consideration of multiple developing cognitive items. The narrative theory applied to fairy tales in this essay will be elaborated on in chapter 2. Additionally, Piaget’s theory supports a potential for interaction between text and children’s cognitive development levels. According to Turiel, children’s interactions with their environments are based on the existing organizations of thought (stages or levels of development) (13). Research shows that children respond differently to the same intellectual tasks when they are at a different developmental stage: findings from Rest, and Rest, Turiel and Kohlberg support the idea that there is an interactional relationship between the individual and the environment that is influenced by the structures of thought (Turiel 14; Rest 86-109; Rest et al. 225-252). The environment of a child consists of many components, and encounters with stories are quite common. Logically, Turiel’s statements regarding the interaction between environment and developmental stage also concern the literature children are in contact with. Turiel indicates that a common approach to this subject of interaction is the use of experiments with children, for instance “the measurement of children’s comprehension of presented solutions with regard to their moral judgments in different developmental stages”(qtd. in Turiel 14). This essay, however, adopts a more theoretical and interactional approach by examining the relations between children’s cognitive development, cultural and Hackeng 5 social influences and the experience of reading fairy tales. The pervading conviction throughout this essay holds that cultural influences decide what kind of fairy tales children experience during their developmental progression; social influences guide children’s perception of the fairy tales through parents’ possible correction of wrongful assumptions about them; and the fairy tales’ structural components possess the potential to stimulate cognitive items children might struggle with during the stages. Although the major focus is on Piaget’s cognitive developmental theory in combination with Propp’s functionalist narrative theory about fairy tales, social and cultural factors are mentioned and will occasionally be referred to. The aim of the essay is to distinguish how, and more specifically, which elements in fairy tales might stimulate cognitive development in children and how this effect is mediated by interactions with social and cultural factors. Hackeng Chapter 1 6 Cognitive Development In order to establish how fairy tale properties can stimulate cognitive development in children, some insight into the concept of cognitive development is required. Research attempts to describe the development of internal mental processes, including memory, language and logic (Leman et al. 20). In his cognitive development theory, Piaget specifically addresses the development of concepts of the physical world such as classification, conservation and number (Leman et al. 255), as well as “underlying concepts such as schemas, cognitive organization and adaptation” (Leman et al. 255). Piaget states that “children actively seek out information and adapt it to the knowledge and conceptions of the world that they already have: … children construct their understanding of reality from their own experiences, and organize their knowledge into increasingly complex cognitive structures called schemas” (Leman et al. 273). His theory emphasizes that children go through several cognitive development stages (Leman et al. 21), each characterized by qualitative changes in the way in which they think and understand the world: as children grow older they progress from using schemas based on overt physical activities to those based on internal mental activities to understand and interact with the environment (Leman et al. 235-236). Furthermore, to understand how these schemas change over the course of the stages and how children understand new experiences, it is important to consider the concepts of accommodation and assimilation (Leman et al. 235). Assimilation concerns the application of existing schemas to new experiences, an often successful process. However, when assimilation cannot be applied to the new situation, accommodation surfaces: the modification of an existing schema to fit the characteristics of the new situation (Leman et al. 235). Hackeng 7 Piaget describes four stages, and each involves a certain age range. The sensorimotor period applies to children aged 0 to 2 years. During this stage “the initial cognitive organizations are constructed that lead to the formation of representational thought and symbolization” (Turiel 12). Children are confined to action schemas and sensory experiences and develop object permanence1 and imitation skills as well as the beginnings of symbolic thought near the end of this period (Leman et al. 237). The second and third cognitive development stages are both named the concrete operational period. However, these stages can be distinguished by the different mental representations that children acquire and experience in these periods: preoperational and concrete operational representations (Leman et al. 237). The final stage is the formal operations stage, in which children are able to make use of logical reasoning and possess problem solving skills. The first concrete operational stage is defined by preoperational mental representations and covers the ages two to seven years (Leman et al. 237). The term “preoperational” is based on the notion that children in this stage have not yet reached a point in their development at which they are capable of operational or logical thought (Doran 63). The second concrete operational stage is defined by concrete operational mental representations and lasts from age seven to eleven (Leman et al. 237). The concrete operational stages mark significant progress in the cognitive development of a child: according to Piaget, in these stages at least ten cognitive deficiencies and difficulties are acquired or solved (Leman et al. 247-252). These cognitive processes are addressed in different stages and occur in a fixed sequence, they are not assumed to develop simultaneously (Leman et al. 237). 1 Object permanence entails that children are able to understand that an object still exists even when obscured from view, and a more progressed form of object permanence able consists of children being to pinpoint the location of an object after it has been moved to several different places in their line of sight (Leman et al. 238). Hackeng 8 First of all, children in the preoperational (concrete operational) period demonstrate animistic thinking, which means they attribute life to inanimate objects (Doran 63). Furthermore, children gradually develop understanding of part-whole relationships during this stage, which is reflected in problems they have with class-inclusion, such as whether a dog belongs to the class of animals or not (Leman et al. 249). Moreover, children in the preoperational stage have difficulties understanding object-quantity, which is demonstrated by their inability to understand conservation. In a task of conservation, when water is transferred from a wide, short glass to a tall, thin glass, children in this stage will reason that there is more water in the second glass than there was in the first because the shape makes the quantity seem larger (Leman et al. 250). Hence, conservation demonstrates the difficulties children have with estimating object-quantity (Leman et al. 251). Additionally, children in the preoperational stage are considered unable to understand reversibility, “the understanding that the steps of a procedure or operation can be reversed and that the original state of the object or event can be obtained” (Leman et al. 251). Moreover, children demonstrate a propensity for centration, which means they “focus their attention on only one dimension or characteristic of an object or situation” (Leman et al. 251). An example of centration is when a child needs to solve a conservation problem but only focuses on the height of the water in the glass, at the expense of other aspects that would help solve the problem, such as the width of the glass (Leman et al. 251). Finally, children in this stage experience difficulties with understanding the concept of transitive inferences, an example of which is to understand that even if one person is taller than another, that person might still be smaller than yet another person (Leman et al. 252). Children in the concrete operational stage generally manage to grasp some of the concepts that elude children in the pre-operational stage, such as understanding reversibility and attending to multiple dimensions at the same time (Leman et al. 252). Furthermore, Hackeng 9 children in the concrete operational stage are able to understand conservation, have no problems with class inclusion and are able to make inferences (Leman et al. 253). An important impairment during this stage, however, is the fact that children can only solve problems and reason logically in this way if presented with concrete reality (Leman et al. 253). Whereas children in the pre-operational stage are mostly unaffected by their inability to distinguish reality from fantasy, children in the concrete operational stage need concrete examples to be able to progress cognitively. In this stage, the importance of social input increases significantly; parents would be sought out more often to provide explanations and may be considered vital to the task of acquiring the desired cognitive capacities by means of reading fairy tales. The fourth and final stage in Piaget’s theory is the formal operational period, which generally commences around the age of 11 (Leman et al. 237). Children in this stage are able to consider multiple solutions to a problem, make use of abstract reasoning and are capable of testing mental hypotheses (Leman et al. 274). As has previously been mentioned, there are other factors to be considered aside from the effects of fairy tales on children’s cognitive development. Not only may fairy tales influence cognitive development, the level of cognitive development may also influence children’s reception of them. This interactional element is also present in two other, closely related phenomena of influence on children’s cognitive development, namely in a sense of reality and level of attention. Piaget maintains, “… the developmental hallmarks of the preoperational stage preclude young children from the strategies necessary to properly distinguish fantasy from reality, as developmentally, their ability to process information is structurally limited. Instead, reality consists of whatever is felt, seen, or heard, at any given moment” (qtd. in Doran 63). In the context of the current theoretical conviction, this means that the fact that children are unable to distinguish reality from fantasy during the Hackeng 10 preoperational stage makes the influence of fairy tales even larger. An event in a fairy tale that might stimulate cognitive development in the child would become as reinforced an experience as a real life experience would have been. Additionally, the element of attention determines to what extent children absorb the stories and their possibly stimulating elements. An interaction between text and cognition is evident in findings that report, “As children get older, the ability to attend selectively increases and enhances children’s ability to learn, … selective attention is an important cognitive strategy (qtd. in Leman et al. 288). Therefore, when children age and progress through developmental stages, they manage to pay more attention to the fairy tale, rendering it more effective as time progresses. However, this concept also implies that children who are in the sensori-motor stage possess very little control over their attention and would be less likely to be influenced by the fairy tale’s stimulating components. This would pose a problem in the current research, were it not for the fact that most children are presented with fairy tales from around the age of three onwards, as has been demonstrated by research into fairy tales that commonly considers children from the age of three (Dickinson, De Temple, Hirschler & Smith 323-346; Botvin & Sutton-Smith 377). In light of Piaget’s theory, the sensori-motor stage will therefore not be considered in this essay. In considering the influence of fairy tales on the cognitive development of children, the omission of social and cultural influences would lead to a rather incomplete image. The social influence consists mostly of the parents’ impact on the reception of the fairy tales. After all, often parents or other carers play an instrumental role in reading books to young children and provide feedback for their child if or when they misunderstand something. With regard to cultural influences, according to Rogoff, Cole and Shweder and colleagues “Researchers who have undertaken cross-cultural studies of Piagetian concepts Hackeng 11 associated with concrete operations have demonstrated the importance of culture in determining what concepts will be learned and when” (qtd. in Leman et al. 253). “This connection between cognitive competence and the cultural context in which development occurs” (qtd. in Leman et al. 253), is also applicable to the area of children’s literature. The importance of both social factors and cultural influences on children’s development is aptly summarized by Bettelheim when he speaks of giving meaning to the life of a child: “… nothing is more important than the impact of parents and others who take care of the child; second in importance is our cultural heritage, when transmitted to the child in the right manner. When children are young, it is literature that carries such information best” (Bettelheim 4). Piaget himself stresses the importance of social influence on the development of children as well: “Social life is a necessary condition for the development of logic. We thus believe that social life transforms the individual’s very nature” (qtd. in Rogoff 33). Hackeng 12 Chapter 2 Narrative theory Fairy tales have not always been part of the children’s literature field. Originally, fairy tales evolved from folk tales that were intended for an adult audience: “fairy tales have been in existence as oral folk tales for thousands of years and first became what we call literary fairy tales during the seventeenth century”(Zipes Breaking 2). In Breaking the Magic Spell, Zipes summarizes the process through which the folk tale has advanced over the years to result in the fairy tale that is known today: “Originally, the folk tale was (and still is) an oral narrative form cultivated by non-literate and literate people to express the manner in which they perceived and perceive nature and their social order and their wish to satisfy their needs and wants”(7). The original folk tales were altered according to the needs of the historical eras and communities as they were passed along the centuries (Zipes Breaking 8). More specifically, the changing purpose of tale telling has constituted a factor for alterations to the tales, unbound by continent or time; for example whether the goal was to entertain or to convey religious history or messages (Thompson 5). Furthermore, Zipes maintains that “Literary fairy tales are socially symbolical acts and narrative strategies formed to take part in civilized discourses about morality and behaviour in particular societies and cultures” (Myth 19). In the field of narratology, the realization of the diversity within the genre of folk tales has lead to a prioritization to classify its subgenres (Propp 4-5). Several theorists assigned classes to folk tales2. However, the boundaries between classes outlined in these 2 Miller classified tales of everyday life, fairy tales and animal tales (qtd. in Propp 5), an approach similar to that of the mythological school of the folk tale which classified folk tales into “mythological”, “about animals”, and “about daily living” groups (qtd. in Propp 15). A problem with this approach is that these categories regularly overlap, as tales relating to animals often also contain elements of the fantastic, or everyday (Morell and Tuck 9). Another approach is Wundt’s division into mythological tale-fables, pure fairy tales, biological tales and fables, pure animal fables, genealogical tales, joke tales and fables, and moral fables (qtd. in Propp 6). The same criticism on Miller’s division applies to Wundt: the Hackeng 13 theories have proven ambiguous and consequently other approaches were to be considered (Propp 7). The classification of folk tales according to plots is another endeavour deemed generally impossible by Propp: “If a division into classes is unsuccessful, the division into plots signals the beginning of complete confusion”(6). Subsequent research into the subject of fairy tales gave way to a new approach that combined Aarne-Thompson’s list of folk tale types with the theory that fairy tales could be deconstructed into so-called motifs, in which recurring functions of the dramatis personae can be identified (Propp 18). With a more viable approach, it would be easier to distinguish subgenres of the folk tale, consequently also identifying what a fairy tales consists of. A narrative structure theorist invented this approach: Russian formalist Vladimir Propp. In his work Morphology of the Folk Tale (1958), Propp is concerned with the analysis of fairy tales (Propp 14). He emphasizes the function of the motifs within the tale as a whole, and maintains that all folk tales can be traced back to a limited number of parts and a limited number of actions that appear in a fixed order (Brillenburg Wurth and Rigney 171). The fairy tales Propp uses in his analysis are identified by Aarne and Thompson as folk tale types 300749, titled Tales of Magic (Aarne & Thompson 19). In their book The Types of the Folk Tale, Aarne and Thompson classify the basic motifs of thousands of folk tales (Brillenburg Wurth and Rigney 169). The concept of motif constitutes an overarching theme within the theories of both Vladimir Propp and the categorization of folk tales by Aarne and Thompson. Motif forms the building block for Propp’s functionalist approach and differing motifs ensure a divergent tale type according to Aarne and Thompson. This focus on motifs arose from the realization within the field of ethnology that variants on the same story emerge in different cultures (Brillenburg Wurth and Rigney 169). It is, however, important to realize that concept of pure depends mainly on personal interpretation, and animal tales can contain moral elements and vice versa (Morell and Tuck 10). Hackeng 14 although Propp’s theory starts out from the concept of the motif, he surpasses that level of the smallest unit by defining motifs in terms of their function (Propp 6). As has previously briefly been touched upon, Vladimir Propp’s theory centres on the notion of functions of the dramatis personae within motifs in fairy tales, these identified as such by Aarne and Thompson (Propp 18). More specifically, this entails that within a fairy tale’s progression, actors perform essentially the same actions, regardless of differences in shape, size, sex, occupation and various static attributes (Richardson 73-74). According to Propp, fairy tales can exhibit 31 different functions and everything but these functions is a variable in them. Not all of these functions may be found within a single fairy tale, but their order of appearance is not affected by the absence of some (Richardson 74). Another layer to this theory concerns a table of 150 elements, which are labelled according to their bearing on the sequence of action, that all fairy tales are composed of (Richardson 74). An example that demonstrates the terms function, motif and element is the following sentence: “Baba-Jaga gives Ivan a horse”(qtd. in Richardson 74). In this example, the motif encompasses the entire sentence, which is then reduced further to four elements, namely Baba-Jaga the donor, Ivan the recipient, the horse as the gift and ‘gives’ signalling the moment of transmittal [the function] (Richardson 74). A detailed list of Propp’s recurring functions can be found in the appendix. Modern narratology has its roots in the work of Russian Formalists, and Propp’s theoretical convictions were a great contribution. He was one of the first narratologists to uncover structures underlying folktales, and to describe them using both formalism and symbolism (Cavazza and Pizzi 1). By means of this approach, Propp managed to assemble a taxonomy to outline the principles underlying the basic fairy tale structure. The fact that his theory provides a generally applicable method for classifying fairy tales makes it the most suitable for the purpose of this essay: examining how and which fairy tale elements stimulate Hackeng 15 cognitive development in children. As this objective concerns a rather broad spectre of factors and research fields, a corresponding, widely applicable literary theory was required. In this context, Greimas’ theory regarding narratology has been considered. The underlying structure in his theory is based on the concept of desire: six variable roles form an action schema about desire that is at the core of every story it is applied to (Brillenburg Wurth and Rigney 172). However, this theory is meant to provide a structure for stories in general, whilst in this essay the focus lies on fairy tales. In a sense, Greimas’ theory is both too limited to provide for a suitable theoretical frame, since it cannot be captured in a taxonomy like Propp’s theory, and too general for the purpose of this essay, as it does not specifically delineate fairy tale structures and consequently offers little insight into their systems. Finally, Piaget’s cognitive development theory and Propp’s functionalist approach to fairy tales share the element of fixed sequence: Piaget maintains that the cognitive progression of children happens according to the passing through stages (Leman et al. 237). This makes it impossible for a child in an early stage to have cognitive abilities that are typically associated with a later stage in the development process (Leman et al. 237). The same assumption underlies Propp’s theory, which entails there is a fixed order to the functions that underlie a fairy tale motif (Propp 24). The only difference between the two theories is that it is possible for functions to be absent in a fairy tale, whilst the skipping of a stage in development is considered impossible. The similarities between the theories with regard to identifiable components in a fixed sequence might facilitate the uncovering of any patterns of relation. Research into fairy tales does not only concern the genre’s structure and classification. After the establishment of the fairy tale, many authors and collectors from different parts of the world endeavoured to collect them from within a certain culture. Some have attempted to make these fairy tales more suitable for a child audience (Zipes Complete Hackeng 16 24). One prominent example of such an effort is the collection and Bowdlerization of fairy tales from Germany by the brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Of the two brothers, Wilhelm Grimm was responsible for more refinement to the style of the tales and he made the contents more suitable and acceptable for a child audience (Zipes Complete 25). Some of the other changes they made to the fairy tales they collected consisted of establishing clear sequential structure in the tales (Zipes Complete 25), for example the addition of logical steps and actions by fairy tale characters3; “the desire to make the tales more lively and pictorial by adding adjectives, old proverbs, and direct dialogue; the reinforcement of motives for action in the plot; the infusion of psychological motifs; and the elimination of elements that might detract from a rustic tone”(Zipes Complete 25). Moreover, the Grimm brothers took care to remove erotic and sexual elements from the tales so as not to offend middle-class morality (Zipes Complete 28). The Grimm’s collection of tales had gained quite some popularity in Germany and German principalities by the 1870s, and even became incorporated into teaching curricula during that time (Zipes Complete 29). However, the main reason for the use of the Grimms’ fairy tales in this essay lies in the fact that the tales, since the start of the twentieth century, “enjoy the same popularity in the English-speaking world [as in Germany and German principalities]” (Zipes Complete 29). Considering a reading audience in both German-speaking countries and English-speaking countries makes the Grimms’ collection very suitable for the purposes of establishing how fairy tales stimulate children’s cognitive development. The tales’ widespread popularity might ensure conclusions about these tales provide a convincing representative of the fairy tale corpus; this is illustrated by the fact that the Grimms’ collection has been translated into 160 languages (O’Neill 1). Moreover, the decision to analyse the Grimm’s fairy tale versions was based on the notion of their relative proximity to the original folktale versions. More 3 These additions were meant to clarify several original tales that progressed from an brief introduction to the proposal of marriage within two sentences Hackeng 17 contemporary versions of some of the fairy tales examined in this essay have been provided by the Walt Disney franchise. According to O’Neill, “In the United States the Grimms' collection furnished much of the raw material that helped launch Disney as a media giant”(1). It could be argued that Disney tales would offer a proper alternative to the Grimm stories as they are circulated through multiple media outlets, and have been censored more thoroughly in order to be politically correct and without violence. However, as Vladimir Propp’s taxonomy is based on premises regarding folk tales, it seemed that fairy tales with features closer to these roots would render more accurate research results. Additionally, since the Grimm brothers assembled their collection in a time when mass oriented sales were not yet the norm, it seemed plausible their versions would make for purer fairy tales without the connotations of the commercialization the Disney franchise has introduced. According to Zipes, “Fairy-tale scenes and figures are employed in advertisements, window decorations, TV commercials, restaurant signs, and club insignias” (Breaking 2). He argues that “in this century at least, so many people know fairy tales only through badly truncated and modernized versions that it is no longer really fairy tales they know” (Breaking 5). The range of fairy tales children are exposed to during childhood is culturally dependent. Perhaps in some cultures, certain fairy tales are considered inappropriate for children or are reserved for older children only. This would impact the notion of cognition stimulating fairy tales negatively, since no exposure or late exposure would eradicate any possible effects. However, the Grimms’ tales popularity and translations into multiple languages, which prove they reach an array of countries, decrease the probability of culture forming such obstacle. Finally, the fairy tales examined in the current analysis are German fairy tales. The German word for fairy tales, Märchen, is agreed to be the most suitable term in the discussion Hackeng 18 of describing tales such as “Cinderella”, “Snow White” or “Hansel and Gretel”(Thompson 8). Other words that attempt to describe abovementioned kind of folk tales often convey some meaning that is either too general, like the French conte populaire, which can be applied to almost any kind of story, or too specific, like the English fairy tale, which implies the presence of fairies whilst the majority of these tales include no fairies (Thompson 8). There is a structure in Märchen tales that is reflected in most well-known fairy tales today: “[it] is a tale of some length involving a succession of motifs or episodes. It moves in an unreal world without definite locality or definite characters and is filled with the marvellous. In this nevernever land humble heroes kill adversaries, succeed to kingdoms, and marry princesses” (Thompson 8). In most fairy tales nowadays, the opening sentence ‘Once upon a time, in a kingdom far, far away….’, reflects the lack of definite location and reality. In the interest of examining non-commercialized tales that mostly adhere to this definition of Märchen and are close to their folk tale roots, this essay centres on the Grimms’ rendering of these ‘fairy tales’, instead of on that of the more recent Disney franchise. The selection considered within the theoretical framework of Jean Piaget and Vladimir Propp has been narrowed down to six rather famous tales: “Red Riding Hood”, “Snow white”, “The Wolf and the Seven Goats”, “Sleeping Beauty”, “Cinderella” and “Hänsel and Gretel”. These tales have also been incorporated into the Disney franchise, due to which it is likely the tales are familiar even if they are not exact replicas of the Grimm tales. Aside from their widespread fame, the fairy tales for this essay were selected for their commonalities in underlying structure: “each narrative begins with a seemingly hopeless situation and … the narrative perspective is sympathetic to the exploited protagonist of the tale”(Zipes Breaking 9). The tale of Little Red Riding Hood does not completely adhere to this principle, as no hopeless situation initiates the story. However, once she has undertaken the endeavour of walking to her grandmother’s house and has met the wolf, it becomes clear Hackeng 19 both Red Riding Hood and her grandmother are facing a difficult situation. Furthermore, near the end of the story, Red Riding Hood once again encounters a wolf, and is hunted by him (Grimm 456). Since both mentioned structures are present in the story, it has been included in the framework for analysis. Research into the effects of fairy tale literature on children’s cognition must draw upon both psychological and literary theories. This research will be conducted through a qualitative analysis of several well-known fairy tales. The analysis of the fairy tales will consist of two components: firstly, the fairy tale will be explored to see whether there are any components in it that might have affiliation with a difficulty or problem from one of Piaget’s stages. Once the components have been identified and described for each fairy tale, the next step is to identify Propp’s functions in them. Additionally, the findings from the fairy tales will be compared to discover whether a pattern or connection can be distinguished in combinations of functions and Piaget’s elements, that influences children’s cognition. Finally, the influence of social factors will be taken into account during the identification of difficulties and problems from Piaget’s theory. For all in-text references of the format (Grimm …) throughout this essay is meant (Grimm and Grimm …). Due to layout shifts this error could not be rectified in time. 4 Hackeng 20 Chapter 3 Elements of the fairy tale In order to present a coherent overview of the findings from the analysis and facilitate the process of uncovering connections between fairy tale and narrative theory, a brief listing of Propp’s 31 functions is provided below (see table 1). A more detailed list of functions may be found in the appendix. Table 1 The 31 functions within fairy tales according to Vladimir Propp 1. Member of family absents self from 16. Hero and villain in direct combat home 2. Interdiction announced 17. Hero branded 3. Interdiction violated 18. Villain defeated 4. Villain tries to meet 19. Initial lack liquidated 5. Villain receives information 20. Hero returns 6. Villain attempts trickery 21. Hero pursued 7. Victim deceived 22. Rescue of hero from pursuit 8. Villain harms family 23. Unrecognized, hero arrives home or other country 8a. Member of family lacks or desires 24. False hero 9. Hero approached about lack 25. Difficult task 10. Seeker decides on counteraction 26. Task resolved 11. Hero leaves home 27. Hero recognized Hackeng 21 12. Hero tested: prepares for magical 28. False hero exposed agent 13. Hero responds to test of donor 29. Hero given new appearance 14. Hero gets magical agent 30. Villain punished 15. Hero transferred to object of search 31. Hero marries and ascends throne Source: Propp, V. “Morphology of the Folktale.” Indiana University Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics, 1958. Print “Cinderella” The first fairy tale appears to contain several elements that might stimulate cognitive development in children. First of all, the animals featuring in the story are named and each is characterised as a different variety, but it is simultaneously made clear that they belong to the same class of animals: birds. “You tame pigeons, you turtle-doves, and all you birds beneath the sky, come and help me to pick”(Grimm 47). These bird varieties are called upon again elsewhere in the story, reinforcing how they are all in the same class of flying creatures, but are still from different kinds amongst that class. Children in the preoperational stage generally have difficulty with class inclusion and may well get confused when asked whether a subspecies belongs to a certain class of animals (Leman et al. 249). Both the mention of different varieties of birds and the repetition of these varieties whilst maintaining they are all in the same class offers a teaching moment to those children struggling to understand. Parents might help their children process that there are different subspecies within a class of animals and help them distinguish those by repeating the described characteristics or linking the mentioned subspecies to another experience the child has had with birds. Hackeng 22 A second cognitive element that features in “Cinderella” is the concept of reversibility. Cinderella’s fate leads her from being the fortunate daughter of a rich man to being the mocked household maid; “They took her pretty clothes away from her, put an old grey bedgown on her, and gave her wooden shoes … there she had to do hard work from morning till night …”(Grimm 47). From that low position Cinderella makes her way up to marrying a prince and living once again in splendour and riches with the help of animals and magic gifts. This plot demonstrates to children that it is possible to reverse the conditions of a certain predicament to a state similar to one previously experienced. Additionally, as in many other fairy tales, multiple characters and events in the story require the attention of the reader. It would therefore be impossible for children to keep track of the story if they were relying on centration: it would make the plotline difficult to understand. The influence of parents could help children sort out what dimensions of the story to pay attention to and could emphasize which elements are more central, and which elements are negligible. This way, children learn to embrace a non-centred approach to events and additionally train their capacity for directing selective attention. Finally, the concept of transitive inferences is reflected in “Cinderella” by the emphasis on different feet sizes and how one foot can be bigger than another, yet still smaller than another. The two stepsisters both have bigger feet than Cinderella, however, the toes of the one sister are larger than those of the other, whereas the heel of the sister with smaller toes is larger than that of the sister with the large toes. This is a good example of transitive inferences and how one object may vary in proportion to multiple other objects. Propp’s proposed functions: 1 -2 -3 -6 -7 -8a -12.7 - 13.7 - 14.5 – 15 -18.2 -19.4 -20 - 21.1 - 22.4 – 23 - 27- 28- 30- 31 Hackeng 23 “The Wolf and Seven Goats” Several cognition-stimulating elements also occur in the fairy tale of “The Wolf and Seven Goats”. Children might better understand the concept of part-whole relationships due to the distinction made between the goats and the wolf. Both kinds of animals are described, first the wolf: “… you will know him at once by his rough voice and his black feet” (Grimm 15). The voice reference may seem incorrect with regard to the real world, but, disregarding the fact that the wolf can actually speak in the fairy tale, it makes sense to describe the sound wolves make as “rough” (Grimm 15). Then, in comparing these two features of voice and feet between the species, it becomes clear that mother goat has a “soft, pleasant voice” (Grimm 15), and white feet. The attention given to the distinction between the class of wolves and the class of goats should help children learn both the concepts of class-inclusion and part-whole relationships: the wolf and goats belong to different species, but they are all part of the overarching class of animals. Furthermore, the difficulties with object-quantity and conservation preoperational children experience are addressed through the wolf’s act of eating six little goats. This event demonstrates that even when a transition to a different physical space takes place, the little goats still maintain the same object-quantity as they did in the original space. Their re-emergence in the same object-quantity disputes the idea that children might have gotten due to their stage, that the object-quantity of the little goats had become smaller after the shift to a more confined space. Additionally, this same event of the goats being eaten demonstrates how it is possible to reverse a situation or state: the goat children are restored to their original state of not-havingbeen-eaten when they are rescued from the wolf. Finally, two other cognitive elements from Piaget’s theory feature in the story: centration and transitive inferences. The multitude of characters and events does not allow children to focus on one dimension only, just like in the Hackeng 24 story of “Cinderella”. Parents might direct children’s attention to crucial elements of the story to help them understand. Furthermore, “The Wolf and the Seven Goats” provides an excellent example of the concept of transitive inferences. When the wolf enters the house, all little goats seek a place to hide: “One sprang under the table, the second one into the bed, the third into the stove, the fourth into the kitchen, the fifth into the cupboard, the sixth under the washing-bowl, and the seventh into the clock-case”(Grimm 15). These hiding places are of different sizes, and as such suggest that the little goats also differ in size: the seventh goat child fits in the clockcase, but it might be assumed that the first goat child, who sprang under the table, would not have fit in there as it chose a roomier hiding place. Moreover, the little goats that hid in the stove and the cupboard would have to have been small enough to crawl in there, but would still have been bigger than the seventh goat child in the clock-case, but also potentially smaller than the goats in the bed or in the kitchen. In this manner, the story introduces children to the concept of transitive inferences. Propp’s proposed functions: 1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 -7 -8 -8a -11 -18 -19 -30 Hackeng 25 “Snow white” The story of Snow white supports three of the cognitive markers as proposed by Piaget for children in the preoperational stage, and also appeals to the logical reasoning and consideration of multiple solutions to a problem of children in the concrete operational stage. Just like in “Cinderella”, in “Snow White” the problem children have with class-inclusion is addressed; again different kinds of birds are mentioned in the context of the overarching animal class they belong to. “And birds came too, and wept for Snow white; first an owl, then a raven, and last a dove”(Grimm 108). The distinction made between these subspecies should, especially in combination with other fairy tales that outline the differences and connecting factor between subspecies, provide children with an increasing awareness of both class inclusion and part-whole relationships. Furthermore, children face the problem of understanding reversibility several times within this one story. Snow white is almost killed twice, the first time by being suffocated with lace “But the old woman laced so quickly and so tightly that Snow-white lost her breath and fell down as if dead… and as they [the seven dwarfs] saw that she was laced too tightly, they cut the laces: then she began to breathe a little, and after a while came to life again”(Grimm 106). During the stepmother’s second trick, “hardly had she put the comb in her hair than the poison in it took effect, and the girl fell down senseless”(Grimm 107), she is thwarted by the seven dwarfs again when they “looked and found the poisoned comb” (Grimm 107). These two instances of close calls with death, ultimately the reversal of the near-death state to the original one, exhibit how reversibility is indeed possible. If preoperational children, before reading this story, believed that actions and states were irreversible, this fairy tale should prove them wrong. This element gains an even stronger emphasis due to the stepmother’s final attempt to kill Snow white: she then appears to truly have succumbed to this tragic fate and has been on display in a coffin for a long time when a Hackeng 26 prince finds her. He moves her coffin, and as a result, the piece of poisoned apple that was lodged in her throat comes loose and she revives once more (Grimm 109). Moreover, the repetition of the tricks of the stepmother and the cautionary words of the seven dwarfs in “Snow white” provide children in the concrete operational stage with evidence of logical reasoning. Whenever the stepmother has consulted her mirror for an answer to “Who in this land is the fairest of all?”(Grimm 105-108), she comes up with a new idea to kill Snow white. Children who read the story might start building connections between emotion and following action plans due to the repetitive pattern of the causes and effects. Additionally, the different ways in which the stepmother approaches Snow white each time in an attempt to kill her give children an example of what it is like to think of multiple solutions to solve a problem. However evil she may be, the Queen stepmother is very resourceful and an encounter with this level of reasoning might enhance solution-directed thinking in children if parents properly guide them in their attempts. Finally, the cognitive problem of making transitive inferences is addressed by means of the beds of the seven dwarfs. As Snow white tries them, “none of them suited her, one was way too long, another too short, but at last she found that the seventh one was right, and so she remained in it …”(Grimm 105). This illustrates that the bed Snow white has chosen has several properties and relations to other beds, and not just one: the bed she picked is smaller than the bed that was too long for her, but is longer than the bed that proved to be too short for her. As this is quite a difficult problem to apprehend, it would be helpful if parents assisted children in their reasoning about Snow white’s choice for a bed. Propp’s proposed functions: 1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6.1 -6.2 -7.1 -7.2 -7.3 -8 -8a -9.6 -12.2- 12.7 -12.8 - 13.1 -18.5 -19.3 -19.8 -20 30- 31 Hackeng 27 “Little Red Riding Hood” An examination of Grimm’s story of “Little Red Riding Hood” also reveals some of Piaget’s notions. In the story, the wolf disguises himself as Little Red Riding Hood’s grandmother after he has eaten her, and awaits the girl in her grandmother’s cottage in order to eat her too (Grimm 55). He succeeds, but then a local huntsman discovers him and rescues her and her grandmother. This is another example of the possibility of reversibility: Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother’s situations are reversed, and all is back to its original state. Furthermore, in this story, there are many elements that make up the plot, so for children to be able to understand the story they need to pay attention to multiple dimensions. The assistance of parents would be useful to this end, as they can guide their children through the story as many times as is needed and provide explanations when necessary. Propp’s proposed functions: 1.3 -2.1 -3 -4.1 -5.1 -6 -7.1 -8.12 -8a -9.2 -10 -11 -12.8 -13.1 -15.2 -15bis -18.5 -19.4 -20 21.4 -21bis -22.4 -30 Hackeng 28 “Sleeping Beauty” The Grimm brothers’ story of “Sleeping Beauty” is similar to that of “Little Red Riding Hood” in the sense that the same two cognitive components as identified by Piaget feature in it. The concept of reversibility is touched upon by two different events in the story. When the twelve fairies that were invited to the castle bestow their blessings on the newborn child, the thirteenth, scorned fairy appears and invokes a curse over the child out of anger for not having been invited to the party: “The King’s daughter shall in her fifteenth year prick herself with a spindle, and fall down dead” (Grimm 100). The last one of the invited fairies then manages to alter the curse by saying that the princess will sleep deeply for a hundred years, instead of dying (Grimm 100). This alteration shows that something that seems inevitable may be changed back to an altogether less permanent state, which calls upon the concept of reversibility. When Sleeping Beauty, and indeed, the entire court wake up again after one hundred years, the full impact of reversibility is demonstrated: everyone returns to their original, pre-curse state of active living. Finally, as with all fairy tales examined in this essay so far, children are confronted with multiple dimensions within one story, and may learn to grasp that outlook in order to understand the story. Propp’s proposed functions: 1 -2 -3 -8 -8a -9.4 -10 -15.2 -19.4 -19.8 -26 -31 Hackeng 29 “Hänsel and Gretel” When the main characters Hänsel and Gretel have succeeded in escaping from the cannibal witch, they encounter the obstacle of what appears to be a lake from the story’s description. In order to reach the other side of it, they call upon the white duck they see in the water to see them safely across (Grimm 35). At this point, Gretel demonstrates a solid knowledge of object-quantity estimation when she replies to Hänsel’s request to come sit with her on the duck’s back: “No, … that will be too heavy for the little duck; she shall take us across one after the other” (Grimm 35). Apparently, Gretel understands that two people make for a heavier weight and larger object-quantity than one person alone, and is able to act on the assumption that there is a certain limit to the object-quantity the duck is able to carry at one time. This insightful moment is not the only instance of logical reasoning in the story: the trick of dropping stones Hänsel develops for his sister and him to be able to find their way back home is one such example, and also draws on the principle of thinking of multiple solutions to a problem, which is a characteristic of children in the concrete operational stage. Other instances of thinking up a solution to a problem are presented in the way Hänsel continuously stretches out a thin bone for the witch to feel when she is trying to assess how fat he has become, and in the way Gretel cunningly feigns a lack of knowledge regarding the oven and goads the witch into positioning herself in such a way that she can push her inside (Grimm 34-35). These examples of logical reasoning and solution-directed thinking may stimulate children in the concrete operational stage to further develop these abilities. Finally, both the cognitive items of reversibility and the problem of centration are reflected in the story. It appears the children face a grim future, having been abandoned in the woods on their own twice, however, they manage to escape and even return home with such wealth that they remove the original cause of their abandonment: poverty. This plotline reveals a return to the original situation, contradicting pre-operational children’s reasoning Hackeng 30 that reversibility is not a possibility. Additionally, this story contains characters, situations, locations and repetitive elements, making it a necessity for children to take multiple dimensions into account rather than rely on centration. Propp’s proposed functions: 1 -2 -4 -5 -6 -7 -8 -8a- 16 -18 -19 -20 -30 Hackeng 31 Chapter 4 Conclusion This analysis has demonstrated that, in fact, there are many cognition-stimulating elements present in fairy tales. Some, namely the concepts of reversibility and centration, feature in all six fairy tales. For children in the preoperational stage, it means that these fairy tales are likely to have a stimulating effect on the acquisition of those cognitive concepts. Their encounter with centration could additionally provide practice in directing attention to the stimuli of their choosing. This exercise is expected to have an enhancing effect on their attention-directing skills. Furthermore, the elements of class-inclusion and part-whole relationships are present in “Cinderella”, “The Wolf and Seven Goats” and “Snow white”. Children’s fairy tale encounters with these preoperational difficulties might increase their awareness of classification systems and facilitate an understanding of the underlying structure of part-whole relationships. An additional aid for the developing minds of preoperational children manifests through the presence of transitive inferences in three of the tales. This is a difficult concept to grasp, since it is generally quite abstractly presented. However, the fairy tales offer some clear examples of the item, and this combined with parental guidance might trigger a better understanding. Finally, in “Hänsel and Gretel” and “The Wolf and Seven Goats”, the preoperational issue of object-quantity is addressed. Gretel’s assessment of the duck combines this item with logical reasoning and should therefore provide quite a valuable stimulus to children’s cognitive development, both in the preoperational and concrete operational stage. In “The Wolf and Seven Goats”, the problem of object-quantity is approached through use of the conservation principle, when the little goats are transferred to a smaller physical location but still emerge in the same quantity when they return to their original surroundings. These Hackeng 32 combinations of cognitive elements may support children’s acquisition of the underlying principles due to the connections they demonstrate, whilst still offering clear examples of the separate components. Only one of Piaget’s proposed cognitive items, animistic thinking, remains undiscovered in these tales. This absence might me due to the current choice of fairy tales, or the item might generally be missing from fairy tales structures. A way of examining which it is, is to conduct a larger research project that includes a wider variety of tales and collections. It appears from comparing the analyses of the fairy tales to the functions identified in them, that there is no direct connection between the number of functions and the corresponding cognitive elements present. The incorporation of many functions in a story does not entail that it will also contain many cognitive components: “Little Red Riding Hood”, for instance, has only two. However, this does not imply that fewer functions in a fairy tale would infer there are many cognitive items present: in “Sleeping Beauty”, there are fewer functions but also only two cognitive items. A proper conclusion would be that there is no identifiable correlation between number of functions and cognitive items. Another possible angle to discover patterns or connections is to compare the functions and cognitive elements occurring in the tales. Disregarding the occasional absence of a function, all the fairy tales contain functions one to eight, which delineates the story from “Member of family absents self from home” to “Villain harms family member” (see table 1). Moreover, function 30, “Villain is punished” is another function that is consistently present. Finally, in every tale but one, both functions 18 and 19 are accounted for. There is some correspondence between these functions and the cognitive elements. From a broad perspective, in all tales that feature functions one to eight, 18 and 19, and function 30, the concepts of reversibility and centration are present. However, this occurrence does not necessarily imply a connection. Since the instances of de-centration vary in place within the Hackeng 33 tales, sometimes encompassing the whole of one, it is difficult to match function to cognitive element. Reversibility, however, may be matched to some functions. As instances of reversibility occur in most fairy tales after the defeat of the villain, function 18, and after a lack has been liquidated, function 19, a possible conclusion would be that this is a pattern of functions and cognition elements in fairy tales. There are no other significant patterns or connections to be found due to the inconsistency of cognitive items in tales and seemingly unrelated functions. It appears that Grimm’s fairy tales are mostly beneficial to children in the preoperational stage: they reproduce many concepts that are difficult for them to understand. Exposure to the preoperational elements in the tales may also render an enhancing effect on concrete operational children’s cognition; however, this would likely take the form of confirmative evidence of their own thought processes. “Snow white” and “Hänsel and Gretel” present children with concrete operational items such as logical reasoning and problem solving, providing them with examples of these skills. Parents might help children make these examples more concrete in order to further their cognitive development. Finally, children in the formal operational stage may benefit from the fairy tales they have encountered by recalling instances of logical reasoning or another item present that could help them solve a current problem or explain a situation. Although the theoretical approach of this essay has rendered significantly positive results, it is important to consider its limitations as well. The theories that equip the current research, Vladimir Propp’s narrative theory and Jean Piaget’s cognitive development theory are relevant to the subject and interesting to consider. However, an exploration of other theories may also offer insight into this particular subject. Although Piaget has greatly contributed to the field of cognitive psychology, some of his notions have been challenged over time and continue to be up for discussion (Leman et al. 244). The same idea applies to Hackeng 34 Propp’s theory: the fact that there are multiple options to go from as a starting point is a drawback and simultaneously an advantage to preliminary research efforts. The narrow range of analysed fairy tales poses another limitation to the current essay. Since only part of the Grimms’ collection has been considered, it would be difficult to draw conclusions that could be generalized to all fairy tales or that could support the creation of the ideal cognition stimulating fairy tale. However, for the purposes of this essay, discovering how fairy tales may stimulate cognition in children, the chosen fairy tale framework suffices. Finally, this research centres on a qualitative approach, and the lack of quantitative evidence makes it difficult to validate the results and enable the elimination of factors on an empirical basis. The time frame and expectations that apply to this essay have accumulated in a fairly cursory research. However, this first exploration does offer knowledge on the subject and leaves space to future research for an expanded undertaking. For instance, Leman and colleagues mention that “Piaget’s ideas have relevance to both education and counselling, which may in turn affect children’s social and emotional functioning” (257). His theory has also been frequently associated with educational practices, for instance with the Montessori school system (Leman et al. 257). Moreover, for therapists, an understanding of the capabilities and limitations that come with these stages might help generate an effective treatment method for children in need (Leman et al. 257). The idea that literature that is already very popular could be used for the purpose of stimulating the development of the young mind offers a range of opportunities for both normally and abnormally developing children. A next research effort might draw on theoretical essays such as this one to formulate a fairy tale that specifically aims to stimulate cognitive elements in children. An application of that kind might prove useful in both educational and counselling contexts. Research that combines theory with empirical testing and evidence, is executed on a larger scale, and takes multiple collections and fairy tales into Hackeng 35 consideration to provide for a more global representation of cultures might be able to render such an application. It appears there have been no other attempts to examine the influence of fairy tales on children’s cognitive development for the purpose of composing a cognitionstimulating fairy tale. However, as earlier research has proven that children’s literature can have an effect on their cognition (Bhavnagri et al. 1), and Piaget’s theory may support treatment for children (Leman et al. 257), perhaps the findings from this essay could provide some foundation for further research. Hackeng 36 Works Cited Bettelheim, Bruno. The uses of enchantment: The meaning and importance of fairy tales. Random House LLC, 2010. Web. 20 Nov. 2014. Bhavnagri, Navaz Peshotan, and Barbara G. Samuels. "Children's literature and activities promoting social cognition of peer relationships in preschoolers." Early Childhood Research Quarterly 11.3 (1996): 307-331. Web. 28 Jan. 2015. Bortolussi, M., and P. Dixon. Psychonarratology: Foundations for the empirical study of literary response. Cambridge University Press, 2003. Print. Brillenburg Wurth, Kiene and Ann Rigney. Het Leven van Teksten. Amsterdam University Press, 2012. Print. Botvin, Gilbert J., and B. Sutton-Smith. "The development of structural complexity in children's fantasy narratives." Developmental Psychology 13.4 (1977): 377. Web. 21 Nov. 2014. Cavazza, Marc, and David Pizzi. "Narratology for interactive storytelling: A critical introduction." Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and Entertainment. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006. 72-83.Web. 23 Dec. 2014. Dickinson, D.K., et al. "Book reading with preschoolers: Coconstruction of text at home and at school." Early Childhood Research Quarterly 7.3 (1992): 323-346. Web. 29 Dec. 2014. Doran, Ruth. "A critical examination of the use of fairy tale literature with pre-primary children in developmentally appropriate early childhood education and care programs." Questions of Quality (2005): 62. Web. 3 Dec. 2014. Hackeng 37 Drabman, Ronald S., and Margaret H. Thomas. "Does media violence increase children's toleration of real-life aggression?" Developmental Psychology 10.3 (1974): 418. Web. 21 Nov. 2014. Franz, von, Marie-Luise. The interpretation of fairy tales. Shambhala Publications, 1996. Web. 29 Nov. 2014. Grimm, J. and Grimm, W. The Complete Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Digireads.com. 2012. Print. Leman, P., A. Bremner, R.D. Parke, and M. Gauvain. Developmental Psychology. McGrawHill Higher Education, 2012. Print. Morell, K., and Penelope Tuck. “Tax and Fairy Tales.” Elsevier 2011. Web. 2 Jan. 2015. O'Neill, Thomas. "Guardians of the fairy tale: the Brothers Grimm." National Geographic 196 (1999): 102-29. Web. 20 Jan. 2015. Peterson, Sharyl Bender, and Mary Alyce Lach. "Gender stereotypes in children's books: Their prevalence and influence on cognitive and affective development." Gender and education 2.2 (1990): 185-197. Web. 21 Nov. 2014. Piaget, J. The Child’s Conception of the World. Paterson, N.J: Littlefield and Adams, 1963. Web. 4 Jan. 2015. Propp, V. “Morphology of the Folktale.” Indiana University Research Center in Anthropology, Folklore, and Linguistics, 1958. Print. Rest, James R. "The hierarchical nature of moral judgment: A study of patterns of comprehension and preference of moral stages." Journal of Personality 41.1 (1973): 86109. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. Hackeng 38 Rest, James, Elliot Turiel, and Lawrence Kohlberg. "Level of moral development as a determinant of preference and comprehension of moral judgments made by others." Journal of personality 37.2 (1969): 225-252. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. Richardson, Brian, ed. Narrative dynamics: essays on time, plot, closure, and frames. Ohio State University Press, 2002. Print. Rogoff, Barbara. Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. Oxford University Press, 1990. Print. Stohler, Sara J. "The Mythic World of Childhood." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 12.1 (1987): 28-32. Web. 28 Nov. 2014. Thompson, Stith. "Myths and folktales." Journal of American Folklore (1955): 482-488. Web. 6 Jan. 2015. Thompson, Stith, and Antti Amatus Aarne. The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography: Antii Aarne's Verzeichnis Der Märchentypen. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1964. Print. Turiel, Elliot. The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge University Press, 1983. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. Zipes, Jack. Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical theories of folk and fairy tales. University Press of Kentucky, 2002. Web. 15 Nov. 2014. Zipes, Jack. The Complete Fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. Vol. 1. New York: Bantam Books, 1987. Web. 3 Jan. 2015. Zipes, Jack. "Fairy tale as myth/myth as fairy tale." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 1987.1 (1987): 107-110. Web. 19 Dec. 2014. Hackeng 39 Appendix 1. Extract from Propp’s book with detailed descriptions of 31 functions 2. Grimms’ fairy tales that were used for analysis Hackeng 40 31 functions by Vladimir Propp (Propp 24-41, 46-57) Hackeng 41 Grimms’ Fairy Tales Some of the names have been adapted to their more recent titles in this essay: “Briar-Rose” “Sleeping Beauty” (Grimm and Grimm 100-101) “The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids” “The Wolf and Seven Goats” (Grimm and Grimm 15) “Little Snow-White” “Snow white” (Grimm and Grimm 105-108) “Little Red-Cap” “Little Red Riding Hood” (Grimm and Grimm 55-56) “Cinderella” (Grimm and Grimm 47-49) “Hänsel and Gretel” (Grimm and Grimm 33-35)