RvN Prose, Appendices, & Bibliography

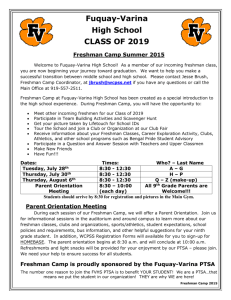

advertisement