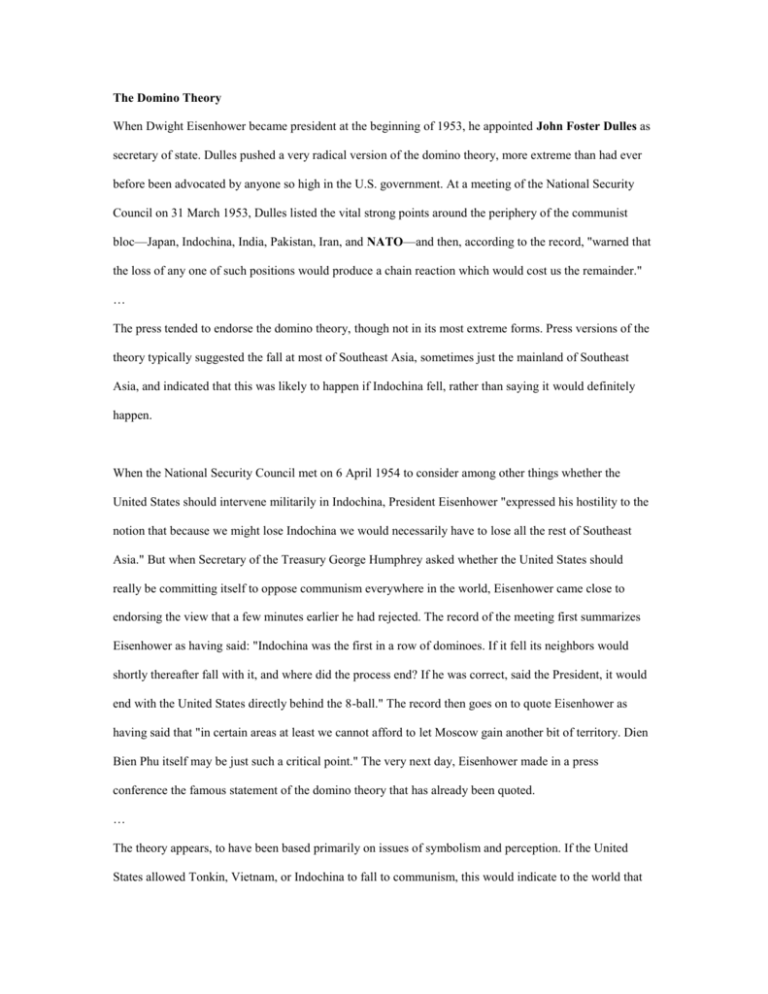

The Domino Theory

advertisement

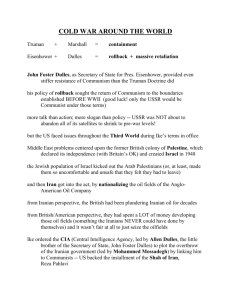

The Domino Theory When Dwight Eisenhower became president at the beginning of 1953, he appointed John Foster Dulles as secretary of state. Dulles pushed a very radical version of the domino theory, more extreme than had ever before been advocated by anyone so high in the U.S. government. At a meeting of the National Security Council on 31 March 1953, Dulles listed the vital strong points around the periphery of the communist bloc—Japan, Indochina, India, Pakistan, Iran, and NATO—and then, according to the record, "warned that the loss of any one of such positions would produce a chain reaction which would cost us the remainder." … The press tended to endorse the domino theory, though not in its most extreme forms. Press versions of the theory typically suggested the fall at most of Southeast Asia, sometimes just the mainland of Southeast Asia, and indicated that this was likely to happen if Indochina fell, rather than saying it would definitely happen. When the National Security Council met on 6 April 1954 to consider among other things whether the United States should intervene militarily in Indochina, President Eisenhower "expressed his hostility to the notion that because we might lose Indochina we would necessarily have to lose all the rest of Southeast Asia." But when Secretary of the Treasury George Humphrey asked whether the United States should really be committing itself to oppose communism everywhere in the world, Eisenhower came close to endorsing the view that a few minutes earlier he had rejected. The record of the meeting first summarizes Eisenhower as having said: "Indochina was the first in a row of dominoes. If it fell its neighbors would shortly thereafter fall with it, and where did the process end? If he was correct, said the President, it would end with the United States directly behind the 8-ball." The record then goes on to quote Eisenhower as having said that "in certain areas at least we cannot afford to let Moscow gain another bit of territory. Dien Bien Phu itself may be just such a critical point." The very next day, Eisenhower made in a press conference the famous statement of the domino theory that has already been quoted. … The theory appears, to have been based primarily on issues of symbolism and perception. If the United States allowed Tonkin, Vietnam, or Indochina to fall to communism, this would indicate to the world that the United States did not have the will to oppose communism. The communists would be encouraged to launch assaults on other countries, and the noncommunist countries, no longer trusting the United States to defend them, would be demoralized and would not resist the assaults. In effect, proponents of the theory appear to have been presuming that the United States could not adopt a policy of defending some areas but not others, because neither the enemies nor the friends of the United States would be capable of understanding such a policy. … The fact that the theory was basically a call to action helps to explain why so few people in the U.S. government chose to apply it to China in the late 1940s. China was very large, and an American commitment to prevent communist victory there seemed likely to be very expensive in money and lives. Few officials had much enthusiasm for a theory that might have obligated them to make such a commitment. Indochina was much smaller, and the prospects for blocking communist victory at reasonable cost seemed much better than in China. American officials therefore were more inclined to endorse a theory obligating them to defend Indochina. … The legacy of the 1938 Munich Conference hung heavily over Americans of Eisenhower's generation. The lesson of Munich, as it was understood in the United States in the 1950s, was that aggression will go on until it is stopped, and that stopping it becomes more difficult the longer one waits to do so. The combined armies of the communist powers were by the 1950s larger than the Nazis had ever had, far larger than would have been necessary to initiate the feared wave of aggression had the communist leaders really been a unified group, with ambitions and daring that approximated Hitler's. American policymakers, seeing that the disaster had not yet happened, did not ask whether they really faced a Hitlerian menace. Instead they worried that even the smallest addition to the total of communist strength would finally trigger the deluge.