- Repository@Napier

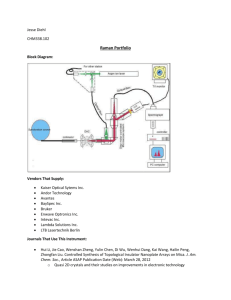

advertisement