Feudal Relations Secondary Readings

advertisement

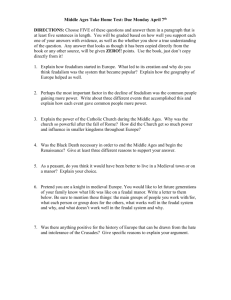

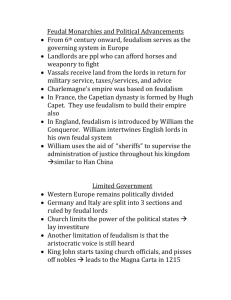

Name: _________________________ Due Next Class Read the following sources and Answer the Following Questions The Carolingian West: The Genesis of Feudal Relationships 1. What are some reasons that historians ‘dispute’ the term Feudalism? 2. Explain why Nicholas argues that ‘feudal relations’ is a more useful (and less problematic) term. An Evaluation of Feudalism 3. List a few examples of feudalism’s “shortcomings” identified by McGarry. 4. What are some examples of “positive” aspects of feudalism political organization? As printed in Dennis Sherman’s Western Civilizations: Sources, Images, and Interpretations The Carolingian West: The Genesis of Feudal Relationships David Nicholas Scholars have long differed over the precise meaning of feudalism. In the following selection David Nicholas surveys this scholarly debate, pointing out some of the problem with the different approaches. He then argues that the term 'feudal relations," emphasizing vassalage and the fief as the key components of the feudal bond, is more useful than the term 'feudalism." Consider: The ways scholars have disagreed over feudalism; why feudal relations might be a better term; the ways this interpretation might be supported by the primary sources in this chapter. The Frankish age witnessed the birth of feudal relations, in the stage that the American medievalist Joseph Strayer called the feudalism of the armed retainer, as distinguished from the later feudalism of the counts and other great lords. The term 'feudalism' has occasioned considerable dispute among scholars. It is applied by Marxists and some capitadist politicians for any economic or political regime that they consider aristocratic or oppressive. Others have identified it with decentralisation of governmental function, but this ignores the fact that those areas where feudal bonds were most completely developed, France and England, became centralised states, while non-feudal Germany and Italy split into numerous principalities. Forces other than extent of feudalisation were involved in these cases, but lords of feudal vassals had a measure of control over their fiefs that princes did not have over allodial (public, non-feudal) land. Some have defined feudalism very broadly, including the non-honourable bonds of serf to landlord as an economic feudalism. Others prefer to avoid the term entirely, since 'feudalism' is a modern word that was not used during the Middle Ages. Much of the confusion comes from the 'all or nothing' approach of some historians. Although some lords compiled lists of their fiefholders, there was never a feudal 'system'. 'Feudal relations' seems preferable, for even feudal'ism' suggests more rigidity than was ever present. Feudal relations developed gradually. We learn much about them in the late Merovingian and Carolingian periods, but the sources then say little more until the eleventh century and particularly the twelfth. When the records recommence, they show that feudal bonds had been evolving in many but not all parts of Europe in the intervening period. For while the word 'feudalism' did not exist, Latin and the vernacular languages had words for vassal and fief, the necessary component parts of the feudal bond. Vassalage was a personal tie of man to lord that developed characteristics that set it apart from other such bonds. The vassal, the subordinate party, owed honourable obligations, notably military service, that did not compromise his social rank. In the language of contemporary texts, he was a'free man in a relationship of dependence'. Not all vassals held fiefs. Princes throughout the Middle Ages continued to maintain warriors in their households. It is inexact to speak of these people as being in a feudal bond with their lords, for they lived in proximity to their lords and did not hold fiefs. The fief was the proprietary nexus between vassal and lord and was held on conditions of tenure that were sharply different from non-feudal property. Vassals who held fiefs were expected to use the income of those properties to pay the costs of performing their own vassalic obligations. They were not maintained directly in the lords' households. Pope Gregory VII (1073-85), whose vassals included Robert Guiscard, the ruler of much of southern Italy, and who claimed the right to give Hungary and England in fief to their kings, would have been astonished at some scholars' notion that he was fighting for a figment of his imagination. Although there was no feudal system, to deny the existence of vassalage and fiefholding is to deny fact. An Evaluation of Feudalism Daniel D. McGarry Feudalism developed gradually during the Early Middle Ages, becoming a prevailing system in many areas between the ninth and thirteenth centuries. By the Late Middle Ages, the feudal system was in decline, though elements of it would remain well into the early modern period. Since the Renaissance, scholars have often evaluated medieval feudalism negatively, emphasizing its weakness and localism. In recent decades, scholars have looked at feudalism more positively, emphasizing its adaptiveness to certain historical circumstances. In the following selection Daniel McGarry evaluates the shortcomings and the positive features of feudalism. Consider: Whether you agree with McGarry's evaluation of what feudalism's "shortcomings" were and what its "Positive" characteristics were; whether the strengths of feudalism outweigh its weaknesses. While feudalism had serious shortcomings, it also rendered valuable services. On the negative side, it resulted in numerous small, semi-independent local governments, incapable of providing many needed public services. Usually roads and bridges were inadequately maintained, while excessive tolls and duties were collected, and brigands and pirates flourished. Excessive emphasis was placed upon personal relationships, to the neglect of concepts of the community and public welfare. The components of the body politic were too loosely bound together by oaths and customs, with a minimum of firm enforceable obligations. The central government was too dependent upon voluntary cooperation and moral responsibility. Obligations were often so indeterminate as to admit of easy evasion. Confusion frequently prevailed, private wars were common, and commerce was severely handicapped. On the positive side, feudalism was a realistic adaptation to existing circumstances: a flexible workable compromise between Germanic and Roman elements. In a time of great insecurity, it provided local defense and government, without entirely sacrificing unity. It was just flexible enough, on the one hand, and just conservative enough on the other, to surmount contemporary challenges yet allow for future reunification. Those states, such as France and England, where feudalism prevailed in the early Middle Ages emerged strong and united at the close of the Middle Ages, whereas those such as Germany and Italy where mixed political patterns were maintained, emerged weak and divided. Feudalism helped to give Western Europe a military proficiency which eventually enabled it to spread its colonies and civilization over the world. It encouraged the contract theory of government, according to which government is the result of a free agreement among the governed; and it contained the principle that all government is limited. Many favorable features of feudalism, first applied only to the upper classes, were progressively extended downward to benefit all the people. Feudal great councils eventually evolved into general representative assemblies, known as Parliaments, Cortes, Estates, Diets, etc. The principle of "No taxation without representation" or "No new taxes without popular consent" is traceable back to the feudal requirement of the imposition of other than customary aids upon the aristocracy. The modem "code of the gentleman," and many of our ideals of courtesy, good manners, and fair play also derive from feudalism.