Attachment A – Treasury Corporation of Victoria PPP Modelling

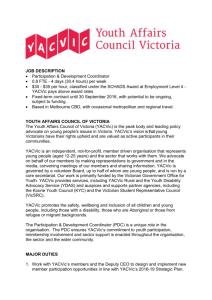

advertisement