theory of hybridization - e-CTLT

advertisement

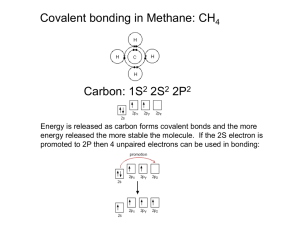

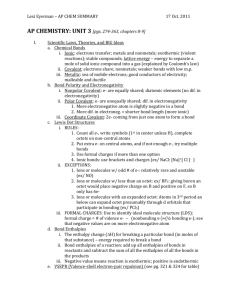

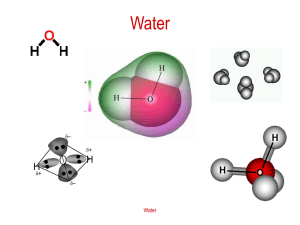

THEORY OF HYBRIDIZATION In chemistry, hybridisation (or hybridization) is the concept of mixing atomic orbitals into new hybrid orbitals (with different energies, shapes, etc., than the component atomic orbitals) suitable for the pairing of electrons to form chemical bonds in valence bond theory. Hybrid orbitals are very useful in the explanation of molecular geometry and atomic bonding properties. Although sometimes taught together with the valence shell electron-pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory, valence bond and hybridisation are in fact not related to the VSEPR model Historical development Chemist Linus Pauling first developed the hybridisation theory in 1931 in order to explain the structure of simple molecules such as methane (CH4) using atomic orbitals.[2] Pauling pointed out that a carbon atom forms four bonds by using one s and three p orbitals, so that "it might be inferred" that a carbon atom would form three bonds at right angles (using p orbitals) and a fourth weaker bond using the s orbital in some arbitrary direction. In reality however, methane has four bonds of equivalent strength separated by the tetrahedral bond angle of 109.5°. Pauling explained this by supposing that in the presence of four hydrogen atoms, the s and p orbitals form four equivalent combinations or hybrid orbitals, each denoted by sp3 to indicate its composition, which are directed along the four C-H bonds.[3] This concept was developed for such simple chemical systems, but the approach was later applied more widely, and today it is considered an effective heuristic for rationalising the structures of organic compounds. Orbitals are a model representation of the behaviour of electrons within molecules. In the case of simple hybridisation, this approximation is based on atomic orbitals, similar to those obtained for the hydrogen atom, the only neutral atom for which the Schrödinger equation can be solved exactly. In heavier atoms, such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, the atomic orbitals used are the 2s and 2p orbitals, similar to excited state orbitals for hydrogen. Hybrid orbitals are assumed to be mixtures of these atomic orbitals, superimposed on each other in various proportions. It provides a quantum mechanical insight to Lewis structures. Hybridisation theory finds its use mainly in organic chemistry. spx and sdx terminology This terminology describes the weight of the respective components of a hybrid orbital. For example, in methane, the C hybrid orbital which forms each carbon–hydrogen bond consists of 25% s character and 75% p character and is thus described as sp3 (read as s-p-three) hybridised. Quantum mechanics describes this hybrid as an sp3 wavefunction of the form N(s + √3pσ), where N is a normalization constant (here 1/2) and pσ is a p orbital directed along the C-H axis to form a sigma bond. The ratio of coefficients (denoted λ in general) is √3 in this example. Since the electron density associated with an orbital is proportional to the square of the wavefunction, the ratio of p-character to s-character is λ2 = 3. The p character or the weight of the p component is N2λ2 = 3/4. For atoms forming equivalent hybrids with no lone pairs, there is a correspondence to the number and type of orbitals used. Thus sp3 hybrids in methane are formed from one s and three p orbitals. However, in other cases, there may be no such correspondence. For example, the two bond-forming hybrid orbitals of oxygen in water can be described as sp4, which means that they have 20% s character and 80% p character, but does not imply that they are formed from one s and four p orbitals. As a result, the amount of p-character is not restricted to integer values; i.e., hybridisations like sp2.5 are also readily described. For more information see variable hybridization. An analogous notation is used to describe sdx hybrids. For example, the permanganate ion (MnO4–) has sd3 hybridisation with orbitals that are 25% s and 75% d. Types of hybridisation sp3 hybrids Four sp3 orbitals. Hybridisation describes the bonding atoms from an atom's point of view. That is, for a tetrahedrally coordinated carbon (e.g., methane CH4), the carbon should have 4 orbitals with the correct symmetry to bond to the 4 hydrogen atoms. Carbon's ground state configuration is 1s2 2s2 2px1 2py1 or more easily read: C ↑↓ ↑↓ ↑ ↑ 1s 2s 2px 2py 2pz The carbon atom can utilize its two singly occupied p-type orbitals (the designations px py or pz are meaningless at this point, as they do not fill in any particular order), to form two covalent bonds with two hydrogen atoms, yielding the "free radical" methylene CH2, the simplest of the carbenes. The carbon atom can also bond to four hydrogen atoms by an excitation of an electron from the doubly occupied 2s orbital to the empty 2p orbital, so that there are four singly occupied orbitals. C* ↑↓ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ 1s 2s 2px 2py 2pz As the energy released by formation of two additional bonds more than compensates for the excitation energy required, the formation of four C-H bonds is energetically favoured. Quantum mechanically, the lowest energy is obtained if the four bonds are equivalent which requires that they be formed from equivalent orbitals on the carbon. A set of four equivalent orbitals can be obtained which are linear combinations of the valence-shell (core orbitals are almost never involved in bonding) s and p wave functions[4] which are the four sp3 hybrids. C* ↑↓ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ 1s sp3 sp3 sp3 sp3 In CH4, four sp3 hybrid orbitals are overlapped by hydrogen 1s orbitals, yielding four σ (sigma) bonds (that is, four single covalent bonds) of equal length and strength. translates into sp2 hybrids Three sp2 orbitals. Ethene structure Other carbon based compounds and other molecules may be explained in a similar way as methane. For example, ethene (C2H4) has a double bond between the carbons. For this molecule, carbon will sp2 hybridise, because one π (pi) bond is required for the double bond between the carbons, and only three σ bonds are formed per carbon atom. In sp2 hybridisation the 2s orbital is mixed with only two of the three available 2p orbitals: C* ↑↓ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ 1s sp2 sp2 sp2 2p forming a total of three sp2 orbitals with one p orbital remaining. In ethylene (ethene) the two carbon atoms form a σ bond by overlapping two sp2 orbitals and each carbon atom forms two covalent bonds with hydrogen by s–sp2 overlap all with 120° angles. The π bond between the carbon atoms perpendicular to the molecular plane is formed by 2p–2p overlap. The hydrogen–carbon bonds are all of equal strength and length, which agrees with experimental data. sp hybrids Two sp orbitals The chemical bonding in compounds such as alkynes with triple bonds is explained by sp hybridisation. C* ↑↓ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ 1s sp sp 2p 2p In this model, the 2s orbital mixes with only one of the three p orbitals resulting in two sp orbitals and two remaining unchanged p orbitals. The chemical bonding in acetylene (ethyne) (C2H2) consists of sp–sp overlap between the two carbon atoms forming a σ bond and two additional π bonds formed by p–p overlap. Each carbon also bonds to hydrogen in a σ s–sp overlap at 180° angles. Hybridisation and molecule shape Hybridisation helps to explain molecule shape since the angles between bonds are (approximately) equal to the angles between hybrid orbitals, as explained above for the tetrahedral geometry of methane. As another example, the three sp2 hybrid orbitals are at angles of 120° to each other, so this hybridisation favours trigonal planar molecular geometry with bond angles of 120°. Other examples are given in the table below. Classification Main group Linear (180°) sp hybridisation AX2 E.g., CO2 AX3 Trigonal planar (120°) sp2 hybridisation Transition metal[5] Bent (90°) sd hybridisation E.g., VO2+ Trigonal pyramidal (90°) sd2 hybridisation AX4 AX5 AX6 E.g., BCl3 E.g., CrO3 Tetrahedral (109.5°) sp3 hybridisation E.g., CCl4 Tetrahedral (109.5°) sd3 hybridisation E.g., MnO4− Square pyramidal (66°, 114°)[6][7] sd4 hybridisation E.g., Ta(CH3)5 Trigonal prismatic (63°, 117°)[6][7] sd5 hybridisation E.g., W(CH3)6 - - Main group compounds with lone pairs For main group compounds with lone electron pairs, the s orbital lone pair can be hybridised to a certain extent with the bond pairs.[8] This is analogous to s-p mixing in molecular orbital theory, and maximizes energetic stability according to the Walsh diagram for the molecule. Trigonal pyramidal (AX3E1) o The s-orbital can be hybridised with the three p-orbital bonds to give bond angles greater than 90°. o Ex. NH3 Bent (AX2E1-2) o The s-orbital lone pair can be hybridised with the two p-orbital bonds to give bond angles greater than 90°. The out-of-plane p-orbital can either be a lone pair or pi bond. If it is a lone pair, the in-plane and out-of-plane lone pairs are inequivalent, contrary to the common picture depicted by VSEPR theory (see below). o Exs. SO2, H2O Monocoordinate (AX1E1-3) o The s-orbital lone pair can be hybridised with the p-orbital bond. The two outof-line p-orbitals can either be lone pairs or pi bonds. The p-orbital lone pairs are not equivalent to the s-rich lone pair. o Exs. CO, SO, HF Hybridization theory vs. Molecular Orbital theory Hybridisation theory is an integral part of organic chemistry and in general discussed together with molecular orbital theory in advanced organic chemistry textbooks although for different reasons. One textbook notes that for drawing reaction mechanisms sometimes a classical bonding picture is needed with two atoms sharing two electrons It also comments that predicting bond angles in methane with MO theory is not straightforward. Another textbook treats hybridisation theory when explaining bonding in alkenes and a third uses MO theory to explain bonding in hydrogen but hybridisation theory for methane. Bonding orbitals formed from hybrid atomic orbitals may be considered as localized molecular orbitals, which can be formed from the delocalized orbitals of molecular orbital theory by an appropriate mathematical transformation. For molecules with a closed electron shell in the ground state, this transformation of the orbitals leaves the total many-electron wave function unchanged. The hybrid orbital description of the ground state is therefore equivalent to the delocalized orbital description for explaining the ground state total energy and electron density, as well as the molecular geometry which corresponds to the minimum value of the total energy. There is no such equivalence, however, for ionized or excited states with open electron shells. Hybrid orbitals cannot therefore be used to interpret photoelectron spectra, which measure the energies of ionized states, identified with delocalized orbital energies using Koopmans' theorem. Nor can they be used to interpret UV-visible spectra which correspond to electronic transitions between delocalized orbitals. From a pedagogical perspective, the hybridisation approach tends to over-emphasize localisation of bonding electrons and does not effectively embrace molecular symmetry as does MO theory.