King William`s War: The Massacre at Schenectady, NY The fate of

advertisement

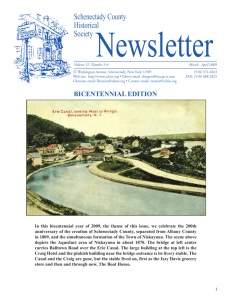

King William’s War: The Massacre at Schenectady, NY The fate of Schenectady was sealed in the middle of January, 1690, when 114 Frenchmen and 96 Sault and Algonquin Indians, most of whom had been converted by the Jesuits, started from Montreal to attack English outposts to the south. It was part of a master plan of Count Frontenac, governor to Canada, to fulfill the commission of French King Louis XIV to "build a new empire in America." They came down across the frozen reaches of the St Lawrence and over the ice of Lake Champlain and finally, in about six days, down to a point at what is now Fort Edward, where the French officers held council on the plan of attack. It was here that they began to compromise with the Indian leaders on the feasibility of attacking Schenectady instead of the original objective, Fort Orange (Albany). Another journey of about 17 days down to the Mohawk Valley brought the war party scarcely two miles from the fur-trading post beside the Binnekill on Feb. 8. It was about 4 o'clock in the afternoon and a blizzard came howling down from the north-west, icy winds swirling snow about the would-be attackers as they huddled in a final council near what is now Alplaus. The French leaders, Lts. Le Moyne de Sainte Helene and Daillebout de Mantet, ordered Indian scouts to cross the Mohawk River and see what precautions the Dutchmen had made against enemy attack. The French were well aware that attack warnings had been posted in the valley communities and they did not know how well the Schenectady stockade might be garrisoned. The Dutchman's fireside on that night of Feb. 8, 1690, glowed with the radiance of humble content. Within the raftered room, its floor and ceiling reflecting Holland cleanliness, he warmed himself before the crackling logs. He was smugly certain that his house was safe from attack - on a night such as this, even the foolhardy Frenchmen would not be expected from the frozen north regions. The scouting party sent to spy on the objective returned to the Alplaus encampment about 11 p.m. and reported to the French commanders that no one was guarding the stockade; even the north gate facing the river had been left open. This information, and the extreme cold, prompted the decision to attack at once rather than wait until 2 a.m. as originally planned. The half-frozen invaders crossed the Mohawk River on the windswept ice and soon were inside the stockade, forming a cordon around the houses that now were quiet with sleep. Suddenly the high-pitched war cries of the warriors split the silence, the signal for a bloody massacre that was to last fully two hours. Houses were quickly put to the torch and inhabitants who came stumbling out in their nightclothes were shot or tomahawked and their scalps taken by the shrieking Indians. Neither woman nor children were spared, and soon their bodies lay along the snow-covered streets, illuminated now by the fitful glow of the burning dwellings. Adam Vrooman, whose house stood on the west corner of Front and Church Streets, fought so desperately that his life and property were spared by the French. It was a tragic stand by the valiant Dutchman, however. His wife and child were killed and his son Barent and a Negro servant were carried away as captives. About 60 persons were killed outright, including 10 women and 12 children. Some managed to escape from the burning stockade area to seek shelter with families some miles distant. It is said that many of these died of exposure in the bitter cold before they got far. The ride of Simon Schermerhorn to warn Albany of the French invasion often is sited as a testimony to the stamina of the Dutch settlers. When the massacre started, Simon mounted a horse and managed to escape by the north gate. Though wounded, he made his way through the snow-drifted Niskayuna Road until he reached Albany about 5 o'clock the next morning. Later, a party of Albany militia and Mohawk warriors pursued the northern invaders and killed or captured 15 or more almost within sight of Montreal. A grim scene greeted the first streaks of dawn as the French rounded up their prisoners and spare horses and supplies to begin the long trek back to Canada. The ruins of the burned homes were steaming mounds beside the blackened chimneys; victims still lay in blood-stained snow where they had been killed or dragged. A party had been sent across the river early that Sunday morning to the Sanders mansion in Scotia. "Coudre Sander" (John A.) Glen was told that he would have the privilege of choosing his relatives from among the prisoners in return for having been kind to some French captives when they were in the hands of the Mohawks a few years earlier. Glen claimed as many "relatives" as he dared. The French and Indians left early in the afternoon with 27 prisoners and 50 good horses. The utter helplessness of the Schenectady inhabitants during the massacre - many offered no resistance since they had no time even to seize their weapons - was shown by the fact that only two of the enemy were killed and one severely wounded. However, aside from the fact that a long and difficult sortie into the English territory had been accomplished, it is doubtful that French authorities considered the mission a great success. By capturing Albany, and perhaps destroying it, the French might have succeeded in detaching the Iroquois from the English besides holding the key to the navigation of the Hudson. But it was not done, and now the whole English province was stirred up like a hornet's nest over the carnage wrought at Schenectady. *** The Dutch village which had begun its settlement in 1662 had suffered a setback so severe, that nearly three decades later, there was some doubt it would be rejuvenated. The uncertainty of future safety of border inhabitants and the utter dejection which prevailed after the massacre raised serious doubts among the survivors as to the expediency of rebuilding the village and cultivating the soil. The township had been depopulated since the massacre. Records of 1698, for example, listed 50 men, 41 women and 133 children - or a total of 224 persons living in the area from Niskayuna to the Woestyne. So for the decade that followed the massacre and closed out the 17th century, Schenectady and its inhabitants presented an unhappy, but industrious, picture of a settlement determined to rise like a Phoenix out of the ashes.