Oppenheimer

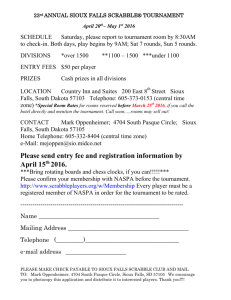

advertisement

Julius Robert Oppenheimer began setting the standard for his scholastic achievements before he ever walked in the door of one of the world's foremost institutions of higher learning. While still a student attending Ethical Culture Society School, a private institution provided by a father that had earned his fortune in textiles, he studied several languages, and cultivated a wide range of interests. He collected languages with great ease, and learned new ones as a means to read literature and poetry in their original form. Once he learned Dutch in six weeks so that he would be able to give a technical talk in the Netherlands. During his final years at Ethical Culture Society School he developed a great interest in mineralogy and chemistry. As was the case with all things that he studied, he became quite proficient and noted in them. His interest in the mineralogy led him to send letters to the New York Mineralogy Club, which found them so insightful that they invited him to present a paper while unaware as to his youthful age. The paper was a complete success. Among those of his own age he fared less well due in large part to his frail and bookish nature. He preferred solitary study to the social aspect of those his age. After graduating at the top of his class from the prestigious school where his father had served on the board of trustees for several years, he took a trip to Europe to pursue his love of mineralogy. While on this prospecting trip he contracted dysentery. The disease had a heavy impact on his already frail nature, and his father brought him home to recover. To help speed his recovery, his father enlisted the aid of his former English teacher, Herbert Smith. Smith took him to New Mexico where the temperate climate sped his recovery, and instilled a joy in horseback riding as well as the American Southwest. The disease kept him out of Harvard for a year, but at the age of 18 he was finally admitted. His major study was in the field of chemistry, but Harvard's rules required him to study history, literature, and philosophy or mathematics. Never one to perform at the minimum level, he made up for his late entry by enrolling in six courses each term for the first year he attended Harvard. The devotion to studies earned him admittance into the honor society Phi Beta Kappa during that first year. Never satisfied with a single field of study, he also partook in independent study involving the field of physics. He performed so well that he earned admittance into graduate standing in physics. Such standing meant that he was no longer required to work on the basic courses, and could devote a larger part of his study to the hard sciences. One of his classmates commented that he "intellectually looted the place." Often his studies of physics were so intense that he was distracted from the "real world." As with many such scholars, along with the feverish bouts of genius came the self-doubts and depressions. While at Harvard he had sent a letter to a friend listing out his varied academic pursuits, and finished the list with "and I wish I were dead." Be that as it may, his admittance into the graduate studies in physics landed him the advance standing to work with experimental physicist Percy Bridgeman. His interest in that field stemmed from one of his courses on thermodynamics as taught by Bridgeman. In addition to the hard sciences, and especially his love of chemistry which he preferred because "it starts right at the heart of things", he continued his studies in English and French literature, as well as the pursuit of philosophy and Eastern religions. He graduated with honors from Harvard in three years, but his studies were only beginning. During his final semester at Harvard, he applied to continue his study at Christ's College, Cambridge. As soon as he received this news he sent an another application to solidify his studies with Ernest Rutherford at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England. Rutherford felt that Oppenheimer's credentials were inadequate and turned down his request. Rutherford had written to Percy Bridgeman for a recommendation. Bridgman's response was to give a qualified recommendation that conceded Oppenheimer's clumsiness in the laboratory made it apparent that his forte was not experimental, but rather theoretical physics. Rutherford was unimpressed, and rejected Oppenheimer's application. Not one to accept a rejection, Oppenheimer sent another application; this time it went to Joseph John Thomson at the Cavendish. Thomson accepted Oppenheimer into his group as a research student, and gave him the task of preparing thin films of beryllium. He regarded the work as a "terrible bore" and pronounced himself "so bad at it that it is impossible to feel that I am learning anything." This from a man whose sole endeavor to this point ahd been to learn everything he could about every subject he devoted his interest to. Oppenheimer was not above taking some of the criticisms personally either. While attending Cambridge he developed a rather antagonistic attitude toward one of his tutors, Patrick Blackett. This likely stemmed from Blackett being only a few years his senior, and was noted as possessing a rather large air of importance. Once, while on vacation with his friend, Francis Ferguson, Oppenheimer confessed that he had left an apple doused with noxious chemicals on Blackett’s desk. Oppenheimer’s parents were alerted by the university’s authorities who were considering placing him on probation. His parents managed to convince them to stop the probation. Likely on this same vacation with his friend Ferguson in Paris, Oppenheimer was in the midst of relating his frustrations with experimental physics. During the conversation things became heated enough that Oppenheimer leapt to his feet and began strangling his good friend. Although Ferguson easily fended off the attack, he was convinced that deep psychological troubles plagued Oppenheimer. The intensity of his studies were taking a toll on the bright young man. He became known as a tall, thin, chain-smoker, who often neglected to eat during periods of intense thought. He was marked by many of his friends as possessing self-destructive tendencies. Upon completing his studies at Cambridge, Oppenheimer travelled to Germany to study under Max Born at the University of Gottingen. The university was widely known as being a world leader in the study of theoretical physics. By this time oppenheimer had shifted his focus from the experimental physics toward the theoretical side, which was more in line with his dislike of laboratory work. While studying at the University of Gottingen, he made several friends that went on to secure their own place in the history books as leaders in the scientific fields, including Pascoul Jordan, Paul Dirac, Werner Heisenberg, Wolfgang Pauli, Enrico Fermi, and Edward Teller. He obtained his Doctorate of Philosophy at the age of 23, supervised by Born. The final exam was administered by James Franck, who alps performed the extensive oral section as well. After the exam was concluded, he was noted as saying, “I’m glad that’s over. He was on the point of questioning me.” Oppenheimer published more than a dozen papers while at Gottingen, often working closely with Born to do so. Having such a prestigious name connected with his work helped many of the papers reach people who would have otherwise overlooked them. One of his more famous papers was on the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation, which separates nuclear motion from electronic motion in the mathematical treatment of molecules. This allowed the nuclear motion to be neglected to simplify calculations. This remains one of his more noted works that led directly to his work in later years. His passion for studying all the intricate aspects of every theory put forth in his classes led him to often hijack the discussions being conducted. This irritated some of Born’s other students so much that Maria Goeppert presented Born with a petition signed by herself and others threatening a boycott of his class unless he could convince Oppenheimer to quiet down. Born left the petition on his desk knowing that Oppenheimer would see it there. It managed to be effective without a word being said. Oppenheimer returned to the U.S. after obtaining his doctorate degree at Gottingen. He had published so many papers while being a student that his return brought offers from many of America’s most noteworthy universities that wanted to include him in their faculty.