sample essay 2 rhet analysis oppenheimer.doc

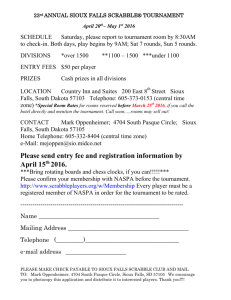

advertisement

Todd Oppenheimer opens his essay quoting Thomas Edison in saying, “the motion picture is destined to revolutionalize our educational system and … in a few years it will supplant largely, if not entirely, the use of textbooks” (255). Education in schools, obviously, is still based mainly on textbooks. Beginning his essay with such a quote, Oppenheimer sets a tone that seems to tell his readers not to listen to all of the hype about new technology, and the promises made with regards this new technology. His purpose is to convince his readers that the emphasis being put on computers in education should be put elsewhere. As previously mentioned, the tone in the beginning of the essay is one that would lead readers to be skeptical about using new technology in education. His disbelief in promises made about new technology is based, he says, on history. “If history really is repeating itself, the schools are in serious trouble.” Oppenheimer writes, “as successive rounds of new technology failed their promoters’ expectations, a pattern emerged… (first,) big promises backed by the technology developers’ research” fail. He says that what happens next is that the technology developers and supporters put the blame everywhere else, except on the technology itself. “As results continue to lag,” he continues, “the blame (is) finally laid on the machines,” but that “soon schools (are) sold on the next generation of technology, and the lucrative cycle start(s) all over again” (256). Oppenheimer brings up several figures that represent the amount of money that is being put in to computerizing schools. He uses figures from several schools across the United States that are spending hundreds of thousands or even millions, as well as the federal government’s billions being spent on computers. Throughout the rest of his essay, Oppenheimer uses studies, real life examples, and his own knowledge to teach us why emphasis should be put somewhere other than computers. Government has its reasons for putting such emphasis on computers. Oppenheimer says that the studies that the government uses to back their reasoning “are more anecdotal than conclusive.” These studies “lack the necessary scientific controls to make solid conclusions possible. The circumstances are artificial and not easily repeated.” He also blames the computer industry for biasing many of these studies. Oppenheimer quotes Edward Miller, former editor of the Harvard Education Letter, saying “most knowledgeable people agree that most of the research isn’t valid. It’s so flawed it shouldn’t even be called research” (260). Oppenheimer blames companies, Apple for example, for using schools to increase business. “In the early 1980s Apple shrewdly realized that donating computers to schools might not help only students but also company sales” (261). Oppenheimer admits that education proceeded to move forward with computers in classrooms, but that this progress didn’t happen until teachers learned how to teach more effectively. Jane David is quoted to have said that what students learned “had less to do with the computer and more to do with the teaching” (262). There are many more effective teaching tools for younger kids than computers, according to Oppenheimer. He brings in an example where a group of second through fourth graders, all being minorities, are taught math on computers. In the middle of telling the reader about this experience for these children, Oppenheimer informs the reader that “The value of hands-on learning, child-development experts believe, is that it deeply imprints knowledge into a young child’s brain, by transmitting the lessons of experience through a variety of sensory pathways. He quotes Jane Healy, an educational pathologist saying, “visual stimulation is probably not the main access route to nonverbal reasoning. Body movements, the ability to touch, feel, manipulate, and build sensory awareness of relationships in the physical world are its main foundations” (264). Bringing up this information in the middle of telling his audience about this elementary school, seems to be intended inform readers, that this way of teaching children mathematics is not a very effective way to teach. Though throughout telling his readers about this school, the teacher seems to be excited about this mode of teaching, Oppenheimer quotes her as having said “I guess I come in here for the computer literacy. If everyone else is getting it, I feel these kids should get it too” (266). Oppenheimer cleverly brings up other elementary schools that use computers in teaching, and shows that computerized teaching is not enhancing, but retarding the education of the children. “Computers suffer frequent breakdowns; when they do work, their seductive images often distract students from the lessons at hand” (267). Here Oppenheimer points out downfalls of the computer itself. Computers require maintenance and knowledge to keep them running. Many teachers do not have knowledge of these high-tech machines to keep them going. Upkeep and problematic computers cost money, money that schools don’t have. Oppenheimer says that one reason “to computerize our nation’s schools” is; “To make tomorrow’s work force competitive in an increasingly high-tech world, learning computer skills must be a priority” (259). More statistics are used to show that jobs do require computer skills more now than before, and that these jobs pay more than those that don’t require computer skills. Oppenheimer agrees that “many jobs obviously will demand basic computer skills if not sophisticated knowledge” (273). Joseph Weizenbaum, emeritus professor of computer science at MIT, claims that “students can learn all the computer skills they need in a summer” (273). Patrick MacLeamy of Hellmuth Obata & Kassabaum, the largest architecture firm in the country says that he doesn’t hire according to computer skills because the necessary skills can be learn in two weeks! One section of this essay is entitled, “The schools that business built” (274). In this section, Oppenheimer claims that “if business gains too much influence over the curriculum, the schools can become a kind of corporate training center-largely at taxpayer expense.” He feels that “traditional liberal arts are being edged out by hot topics of the moment or strictly businessoriented studies” (274). Oppenheimer states that computer hardware and software being used in high schools and elementary schools may bias what these kids decide to do with their lives. He says that some schools have gone as far as to trade with companies. “In return for donating funds, businesses can specify what kinds of employees they want.” Thus in some cases “business is increasingly dominating school software and other curriculum materials, and not always toward purely educational goals” (275). This biased teaching proves to be problematic in more ways than one. Along with an education that is not well rounded, “changes in the classroom for which business lobbies rarely hold long-term value.” So when the economy changes, “workers are left unprepared for new jobs… This is one reason that school traditionalists push for broad liberalarts curricula, which they feel develop students’ values and intellect, instead of focusing on today’s idea about what tomorrow’s jobs will be” (275). Oppenheimer strongly encourages a well rounded education that will be beneficial to the student, no matter what happens in the economy. Oppenheimer says that in many schools that are high-tech, teachers are proud to show that their students are able to expand their knowledge and experience via the web. Students are now able to speak to people around the world at the click of a button. Oppenheimer does feel that “the internet when used carefully, offers exciting academic prospects”, but he cautions that this is “for older students.” He points out how easy it is to have something published on the web. Supporters of using the web in teaching praise the fact that students are able to publish their studies on the web, and this “gives young writers their first real audience.” Oppenheimer does not share this same excitement for the web. He states, “The free nature of internet information also means that students are confronted with chaos, and real dangers.” He agrees that there is much information on the web that can be useful to many, but cautions that “older students may be sophisticated enough to separate the net’s good food from its poisons, but even the savvy can be misled” (278). Steven Kerr, professor at the University of Washington, feels that use of the web, due to its free nature, is “the antithesis of what classroom kids should be exposed to.” Kerr gives another reason for his dislike of the web. He says that, “If you find a useful site one day, it may not be there the next day, or the information is different. Teachers are being asked to jump in and figure out if what they find on the net is worthwhile. They don’t have the skill or time to do that” (279). Many feel strongly about the importance of actual books in the teaching process. Sherry Dingman, of Marist College in New York, thinks that bypassing books in education will cheat a child’s imagination. She said, “If we think we’re going to take kids who haven’t been read to, and fix it by sitting them in front of a computer, we’re fooling ourselves” (280). The act of reading a book and allowing the imagination to bring it to life is an important aspect to development of a child. Oppenheimer calls computers “just a glamorous tool.” He feels that the movement towards using computers to educate “is not just the future versus the past…; it is about encouraging a fundamental shift in personal priorities-a minimizing of the real, physical world in favor of an unreal virtual world” (281). He feels that this movement could cause more damage than movements to revolutionalize education have in the past. Oppenheimer says that computerized education will do more that just dehumanize things, “it may also limit the development of children’s imaginations. He is not saying that computers are bad, but that “You’re not going to solve the problems (in education) by putting all knowledge onto CDROMS. We can put a web site in every school-none of this is bad. It’s bad only if it lulls us into thinking we’re doing something to solve the problem with education. Oppenheimer closes his essay by bringing back his example of television being a historical promise to revolutionalize education. He writes, “Computer enthusiasts insist that the computer’s interactivity and multimedia features make this machine far superior to television.” Oppenheimer warns educators to beware of the business side of this movement. He feels that due to the push to get computers in, that “if schools can impose some limits… rather than indulging in a consumer frenzy, most will probably find themselves with more electronic gear than they need.” This he feels will help the lack of funding in schools. He continues, “That (not indulging in the frenzy) could free the billions that Clinton wants to devote to technology and make it available for impoverished fundamentals” (282). “Tools come and tools go. Teaching our children tools limits their knowledge to these tools and hence limits their futures,” says Michael Bellino, an electrical engineer of Boston University’s Center for Space Physics. This is what Oppenheimer is trying to say. Computers are not the way to educate. Computers are tools, and should be used as such. The educational system needs to be helped, so that kids will be taught effectively, however, computers are not the solution to the educational system’s problems.