The Egyptian Military and Democracy Management

advertisement

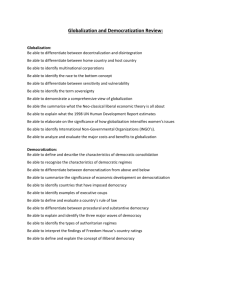

The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 The Egyptian Military and Democracy Management Birthe Hansen and Carsten Jensen1 Abstract Two military coups d’état took place in Egypt in 2011-13: the first ended the authoritarian rule of the Mubarak regime in 2011, the second ended the rule of the elected president Morsi. The paper analyzes whether the second coup indicates an end to the process of democratization in Egypt and, consequently, to a theoretical hypothesis on the military’s new role. It is argued that the military also in 2013 undertook ‘democracy management’, and that the political turmoil rather reflected a struggle over two paths to liberal democracy emphasizing the liberal respectively the democratic content. Since 2001, a series of old authoritarian regimes have fallen within the Greater Middle East: the Taliban-regime in Afghanistan (2001), the Saddam Hussein-regime in Iraq (2003), the Ben Aliregime in Tunisia (2011), the Hosni Mubarak-regime in Egypt (2011), and the Gaddafi-regime in Libya. In all the five cases, armed forces (national, international or a mixture) were important to the fall of the old regimes. In all five cases, too, the regimes were replaced by the initiation of processes of democratization, in which armed forces were also instrumental. In Egypt, however, the military displaced the elected President, Muhamed Morsi, in July 2013 only two years after the fall of the authoritarian Mubarak regime. This raises the questions of whether the process of democratization has come to an end, and whether the Egyptian military inherently is an anti-democratic actor. It has been argued that the military is so strong and power seeking that a new military order is probably emerging (Springborg, 2014; Albrecht and Bishara, 2011). However, it has also been argued that the pressure from the current unipolar world order tend to draw the actors in the direction of democracy, and that even Arab militaries tend to adapt to a role as democracy managers after the fall of the old regimes according to the socialization thesis (Hansen and Jensen, 2013). An additional question is therefore whether the recent case of Egypt challenges the socialization thesis. 1 Birthe Hansen, Institut for Statskundskab, bha@ifs.ku.dk and Carsten Jensen, Copenhagen Middle East Research, Carsten.jensen@ifs.ku.dk. 1 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 The process of democratization in the five states has revealed common elements and two paths to be pursued. We argue that the July coup in Egypt is not necessarily the end of the democratization process but that it rather reflects an intense political struggle over which path to choose: The Egyptian military is struggling for development of a model that favours the liberal part of a liberal-democracy model while its counterpart organized around the Muslim Brotherhood favours the democracy part of the model. The paper thus analyzes the role of the Egyptian military in the transition process from authoritarianism into democratization. The process is still open-ended, and the ‘final’ result lies probably many years ahead, but it is still possible to identify trends and milestones in the process and assess the compatibility with further democratization as well as to evaluate the role of the Egyptian military in this process. Having ‘killed’ statements like ‘military means cannot bring about democracy’ from the start, the paper proceeds as follows: 1) The military and the ousting of the Mubarak regime, 2) the military and the process of democratization, 3) the struggle about the Egyptian model for democracy, and 4) conclusions. The military and the end of the Mubarak regime Inspired by the Tunisian turmoil, protests in Egypt evolved in early 2011. From the beginning, demands for the withdrawal of President Hosni Mubarak were in front, and the demonstrations soon escalated and took a national and organized form based on an array of demands – but mainly political. The Egyptian military is a crucial societal actor, well institutionalized and enjoying a high degree of popular support (Jensen, 2011). During the first week of the Egyptian revolt it provided political support for the Mubarak regime and asked for ‘order’. As the demonstrations further increased, the forces of the Ministry of Interior and the police corps could not handle the situation but the army refused to intervene or use violence against the protesters and it began to cool down its political support for the regime. Two weeks after the revolt took off the army carried out a coup d’état against the Mubarak regime and removed it from power thus conducting an end to the old regime (Hansen and Jensen, 2012). 2 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 In the case of Egypt, large-scale national demonstrations produced a tense political situation, and the regime change came about by means of an active national military intervention. By ousting the Mubarak regime, the Egyptian military broke previous patterns of Arab military behavior. It has been established that Arab militaries since about 1970 predominantly have adopted role of authoritarian regime protection (Rubin, 2002), and in the case of Egypt this has particularly been the case since 1973 after the series of military defeats to Israel. Deciding not to counter the protesters as well as to displace the government thus strongly indicate a break with the previous patterns. The Egyptian case is in this respect similar to the cases of Tunisia and Libya. Weeks before the fall of Mubarak, Tunisian President Ben Ali had to flee the country after the Tunisian army and other parts of the security sector pulled out the rug under his regime following massive popular and organized demonstrations (Lutterbeck, 2011). In Libya, violence erupted after demonstrations in the spring of 2011, and parts of the regular army deserted or joined the rebels. By means of international military support, the rebels ended the Gaddaffi regime in August 2011, and Muamar Gaddaffi was killed in his hometown of Sirte in October. However, breaking previous patterns of authoritarian regime protection is one thing, another thing is whether the army has been able to adapt to challenges from current unipolar world order, most notably the pressure for socialization that includes democracy (Hansen, 2011). The military and the on-set of democratization A new role for Arab militaries has been conceptualized as ‘democracy managers’. The term refers to a “unified military that carries out democracy promoting actions in authoritarian or transitional societies by means of violence or with the implicit or explicit threats of use of violence” (Hansen and Jensen, 2013, p. 4). More specifically, the role implies that the military is Being an active partner in planning and coordinating the transitional process from an authoritarian regime towards democracy Supplying and maintaining domestic social order during the transition process that frames the process and allows electoral democratic processes to unfold Professionalizing themselves in the sense that they differentiate themselves from civil politicians and society, protecting the development of an independent civil 3 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 political life and avoiding to side in sectarian struggles during transitions (Ibid., p. 5) Although securing some level of social order is typically considered a precondition for the development of democratization (Linz and Stepan, 1996), in this paper we focus at the democracy promoting actions and leaves the other part of the democracy manager role aside. The next task is therefore to consider whether the Egyptian military has conducted democracy promotion after the 11th of February 2011. When assuming power, the leader of SCAF, Field Marshal Tantawi promised to lift the emergency laws and that free parliamentary and presidential elections should be conducted before the end of 2011. The parliamentary elections were held between November 2011 and January 2012, elections for the Shura Council2 took place in January-February 2012, and President Morsi was elected in June, 2012. SCAF declared a provisional constitution after its takeover, and this consisted of some liberal amendment to the existing constitution, and work to prepare a new one was set in move. A fully new constitution was adopted after a referendum in December 2012. The turnout was only one third of the voters, and of these two thirds chose to approve the proposal. The new constitution reflected that the Egyptian Islamists had been highly influential in the drafting process but this was accepted by the military. After the July 2013 coup, however, SCAF suspended the new constitution temporarily and planned for the preparation of another and a following referendum. Mohamed Morsi remained President about a year from June 2012 to July 2013. During this period he issued decrees in the autumn of 2012 that expanded his power and prevented judicial review of his acts. In July 2013, the military displaced President Morsi, imprisoned parts of the opposition – mainly Morsi-loyal leaders and activists belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood. SCAF, now headed by General al-Sisi, established a new provisional government and appointed supreme court judge Abdel Mansour to be the acting President. In September, a court ruling banned the activities of the Muslim Brotherhood and ruled to confiscate its assets3. Judged on its formal actions, a number of these qualify the Egyptian military as ‘democracy manager’: its participation in ending the rule of the old authoritarian regime, its planning of the transition process, the implementation of the series of elections (parliamentary, 2 The Shura Council is the Upper House in the Egyptian Parliament and is, in principle, consultative. It has, however been entitled to legislative functions after the dissolution of the parliament. 3 http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/09/23/us-egypt-brotherhood-idUSBRE98M0QR20130923 4 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 shura and presidential), the initiation of the preparation of a new constitution and the implementation of the referendum. However, also some ‘dubious’ formal actions took place: the displacement of the elected president, the suspension of the new constitution, the imprisonment of political opponents and the prevention of their activities. The newly elected parliament was dissolved in the summer of 2012 after a supreme court ruling but the dissolution is not included in the ‘dubious’ actions: the representatives elected were not contested but the court ruled that the conduction of the parliamentary elections was not law-compatible as the new constitution was not yet adopted4. The next section analyzes the ‘dubious’ actions and the struggle for a possible path to democracy in order to assess whether the actions are compatible with the role of democracy manager and to what extent the actions of the Egyptian military comprises the socialization thesis. The toolbox model and the two paths The recent processes of democratization in the Greater Middle East appear to have followed a model, which we label ‘toolbox model’. It consists of five elements in a succession that may vary according to the way the process is initiated. The five elements are: 1) The establishment of an interim government, 2) the election of a constitutional assembly, 3) a referendum on a new constitution, 4) parliamentary elections, and 5) presidential elections. The ‘toolbox’ model summarizes the elements in the process that follows a trial of strength when an authoritarian regime is contested and falls. The new government is not grounded in any of the political forms that could legitimize it but based on power over its former enemies and a new constitutive form. If the democratic impetus within this polity or the pressure for democracy from the outside is strong enough it is possible to start a process towards democratization. However, during the initial process of democratization two ideal types seem to describe the specific use of the toolbox elements: The one is characterized by a formalistic progression of events designed to build a legitimate liberal democratic political system, where the most basic elements are put in place before the more elaborated and complex elements. This model gives priority to ‘rule of law’, that is the ‘liberal’ part of liberal-democracy. The other path comprised the same elements without the 4 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jun/14/egypt-parliament-dissolved-supreme-court 5 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 consecutive order. Instead, it is characterized by a more ad hoc or improvised order, as those in charge of the decisions to establish institutions take the decisions according to politics as ‘the art of the possible’, and this path gives priority to the ‘democratic’ part of liberal democracy. The ‘liberal’ path seems to be the fast (and most linear) way to obtain legitimacy during the current world order, at least internationally. This path comprises the election of a council with the purpose of drafting a constitution. An internationally acceptance of such a council facilitates the sustainment of the new state as it becomes eligible for support from leading states, particularly the United States. Afghanistan and Iraq had to accept this path, at least in the immediate aftermath of the political transformations. The next step is to get acceptance of the proposal for a constitution. This provides the new government domestic in addition to international legitimacy. Based on the constitution, legitimate parliamentary and presidential elections can take place, and if these are conducted fair, free and at a universal basis, true democratization is taking place. If this election of leaders is repeated, minimal democracy has been established according to Samuel Huntington (1991). This has been the case in Iraq and, to a lesser extent, Afghanistan during the past ten years. The ‘democratic’ path has been followed by Egypt, Libya and Tunisia that became democratizing countries between 2011 and 2012. Initially, SCAF tried to implement the liberal path in Egypt but had to change its strategy before the adoption of a new constitution and proceed with parliamentary elections instead. As mentioned, the democratic path still comprises the elements of the toolbox model but without a fixed consecutive order. These civil dimensions of democratization have corresponding military roles in the current world order: as benign security provider in a state in transition, as democracy managers during democratization, and as a democratic military (or guardians of democracy) in a new democracy. Table 1 depicts the civil-military relations in the different stages: Table 1: Civil-military relations in stages of transition from authoritarianism according to an ideal model Establishment of ‘principal Civil dimension Civil-military dimension Preliminary Government Establishment of controlled order’/civil order security order beyond the old (eliminating violence as a order (Military still no formal mean of civil political struggle) legality – military means are 6 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 simply ‘in the hands of the strongest’) Development of new order Election of constitutional Military as democracy assembly managers Referendum on Constitution Parliamentary elections Presidential elections (Maintenance of new order) (Repetitions of 4 and 5) (‘Democratic military’) After 2001, the process in the Greater Middle East resembles this ideal model of the development of civil-military relations in the states that have left the authoritarian forms of government that originated during the Cold War. The order of implementation of the elements depends on the political relations of strength and the visions of domestic actors. In Egypt the main events in the struggle for democratization were in institutional terms the following: 1. Referendum on preliminary changes to the constitution, march 21, 2011 2. Parliamentary elections, November 2011 to February 2012 3. Elections for Shura Council, January and February 2012 4. Presidential elections, June 2012. 5. New amendments expanding presidential power, October 2012 6. Referendum on new constitution, December 2012 7. July, 2013. Military displacement of President Morsi and new quasi military government with civil president The first four of these events clearly differs from the pattern of liberal democratization. The succession instead shows a pattern that emphasizes democratic elements. After President Morsi came to power first expanded his own powers and then put a proposal for a new constitution on the agenda for a referendum. The proposal was accepted by voters but as mentioned above with a very low turnout. As a whole this series of events in principle produces a kind of institutional framework for national politics that seen in isolation provided a full liberal democratic institutional set up. In reality its legitimacy was very small. In the end the displacement of Morsi ended the first Egyptian experiment with a democratic way to liberal democracy based on ad hoc political reform projects. It 7 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 is argued later in this paper that this is an end of a specific road to liberal democracy. Not necessarily an end to democratization as such. The Struggle for liberal democracy in Egypt 2011-2013 The main contenders in the struggle for democracy in Egypt after the 25 January revolution have all been publicly and explicitly in favor of liberal democracy. The principles of free speech, independent civil society organizations including parties, rights for every citizen to run for public offices, rights to vote in free and fair elections were accepted by all main players. There have been arguments in all camps for restrictions for opponents, accusations of lack of democratic spirit etc, in spite of such outbursts, the main support of the leading actors to the principles has been strong. Still, it obvious that the parties in Egypt after the ousting of President Mubarak has had various ideas of how to get from authoritarian state structures to a liberal democratic structure. The parties have not agreed on the road to democracy and they disagree on basic issues concerning society (as opposed to the state). The most important issue has been on the role of Islam. Should Egypt be a multicultural society including both secularists, Muslims and Christians or should it be a society in which the Muslim way of life ruled? Furthermore, they have not agreed on who should be the leading parties. Each of them has struggled to ensure and maximize their position in the new Egypt. The various policies on these big issues point to four main lines in politics in Egypt today within the broad liberal democratic consensus. There are also political actors outside this consensus but so far they have had so little influence that it is possible to neglect their presence in the identification of the main political positions5 which are depicted in figure 2: Figure 2: Principal groups within the liberal democratic consensus in Egyptian politics Secular Religious State based The military: Soldiers, senior The Muslim Brotherhood, administrative leaders, professionals, etc. Local pensioned officers in both political leaders, Middle class public and private people. organization, some Christians Civil society based The liberals: Salafists: local, rural leaders They include some radical Islamists, small Marxist groups and various political and social groups that also democratic societies today include. 5 8 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen El Baradei group, NSF, New Capitalists, Young liberals (for instance Rebel or, April 6 movement), Many Christians 201013 based on traditional life styles. ‘The underdogs’ of Muslim communities The Military have acted as ‘the party’ of the state based secularists. They did very well in the presidential elections and were only a few percent from beating the winning candidate Morsi in the last real elections in Egypt before the ousting of Morsi. Their preferred road to democracy goes through a liberal ideal succession of events that shares its features with those that guided (and were materialized in) Afghanistan’s and Iraq’s road to democratization. The Muslim Brotherhood founded their own party (the Freedom and Justice Party) based on two ideas: Islam should be a part of politics in Egypt and the political systems should be democratized. That is, they want a state based on liberal democracy and a civil society based on Islam. The liberals, which includes a variety of groups, agree on the notion of liberal democracy, but differs with the Brotherhood concerning many other issues. They do not accept the idea of an Islamic civil society, although they argue that Islam should be legal within the limits of tolerance and the equal rights of Christians and non-religious groups. Their ideas and inspirations refer to Egypt’s liberal past as well as to current ideas on globalization and the spread of democracy in new forms. Both ‘social movement’ politics in contemporary European styles and ‘capitalist’, neoliberal ideas are represented in this group. Finally, the Salafists represent an Islamist alternative to the Brotherhood. The Salafist Nour Party is at the same time more radical and more conservative than The Freedom and Justice Party. It is more radical in its social demands and represents workers and peasants living in circumstances different from the middle classes represented by the Brotherhood. They are also more conservative in the sense that they promote traditional rural based life styles. These broad political lines frame the fighting about the right and ability to define the institutional framework around liberal democracy. Of course, it is possible that none of them will win, and that their mutual disagreements and politics will create a stalemate that will keep Egypt away from democratic development for many years to come. This could give rise to new authoritarian strands within the military, the Islamists and the new capitalists that could agree of 9 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 some sort of recreation of the basic features of the Mubarak state. Today this scenario cannot be ruled out, but it is by no means the most likely outcome. Instead the likely outcome is that the military defines the roadmap (the liberal model) while some compromises are made with the religious groups, that allows acceptance by both Christians and Salafists. The contemporary challenge to the Egyptian politics is (apart from the struggle between the parties about their own positions and interests and the question of the multicultural or Islamist interpretation of civil society) that liberal democracy comes in various forms and sizes. The various models come from the fact the ‘liberal democracy’ is not a pure political form, but a mixture of two principles, that are not completely compatible: political liberalism and democracy. The Canadian political scientist G.B. MacPherson was one of the first to point out, that the liberal democracy of the 20th century was a paradox. It is a combination of two ideologies that in the most of the 19th century were opposed to each other. From the beginning of the 20th century, the two ideologies eventually began two merge into a single political regime. Starting in Australia, Norway and New Zeeland before World War I, liberal democracy began to spread. According to Samuel Huntington (1991) there have been three major waves of democratizations in which this model has spread around the globe in various national forms. In most cases the struggle has been abour democracy or not but in the Egyptian case the most important issue appears to be about which principles should guide the transition to full liberal democracy: the liberal principles of ‘Rule of Law’ (Der Rechtstaat) which seems to be the military’s first concern or the democratic principles of representation (which was supported by Mohamed Morsi). The two dimensions of liberal democracy will always be in partial conflict. The liberal principle of protection of individual rights, for instance to decide how personal income is spend, can be opposed to the rights of the elected decision makers to determine the level of taxation. The materialization of one of the principles may undermine the other. This feature of liberal democracy is a part of its dynamic character and ensures that such a regime will never settle in a fixed form. On the other hand it continuously creates potential conflicts. In a society in transition (and with no stable and commonly accepted political rules) it also provokes conflicts around a proper interpretation of a commonly accepted political goal, even 10 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 among political forces each committed to a realization of a democracy compatible with the principles of the New World Order. The struggles in Egypt in after the military intervention in July 2013 evolve around the questions of where to start. Should the point of departure be the liberal dimension and the adoption of a constitution that can guide the further process or should it be the election of politicians that can guide the process? In principle these whether ‘the rule of law’ or ‘the rule of man’ constitute the best starting point, in which the constitution represents ‘the law’ and the elections to representative assemblies represents ‘man’. In reality, both founding principles will be decided by political actors acting more or less in concert and conflict, but for the Egyptians today, who has been though a period of reform which was dominated by the democratic principles of elections of representatives (parliament and president) without a proper liberal democratic constitution the change – as proposed by the military – to a process where a new constitution will come first will be a real change in the course of the democratic revolution. The Brotherhood The Muslim Brotherhood appears to have counted on the democratic way as their best bid for power. They opted for free and fair elections of a president. Mohamed Morsi was elected that way and the demand for his reinstatement is therefore legitimate from the point of view of democracy. From a purely democratic perspective it was a scandal that he was displaced by the military. From other perspectives, Morsi’s legitimacy was less obvious. He supervised the development of a constitution in November 2012 that got little support. A third of the constituency took part in the referendum and of them two thirds voted yes. The new constitution has thus far from a majority behind it. Furthermore, before the referendum Morsi attempted to provide himself with almost absolute in order to prevent his decisions to be tried through the legal system. Since one of the Muslim Brotherhoods favorite tactics during Mubarak’s regime was to use the legal system against their opponents some felt it was a bit ‘big’ of Morsi to try to deny his subjects this possibility during his rule. Both series of events eroded much of the subjective legitimacy that he might have gained by the victory in the presidential elections. Mohamed Morsi thus had a democratic victory behind him as president but his opponents developed a sense of betrayal based on other dimensions of the conception of liberal democracy, that is, the various dimensions of liberal democracy clashed under Morsis rule. 11 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 At the same time the Morsi state was still a long way from liberal democracy. The Egyptians had elected a parliament in the winter of 2011/12 in elections that in principle were free and fair. But the Supreme Constitutional Court had judged the rules behind the parliament as nonlegal because they were based on laws not accepted. This implied that the parliament had never worked in a political sense (it had not really met) and Morsi had to rule without the support of legitimate law makers. Egypt was thus caught in a web of principles contradicting each other and coming from various non-compatible political traditions. The balance between constitution, parliament and president did not exist and the liberal protection of the citizens and their political rights did not balance the democratic rules that had made Morsi’s victory in the elections possible. When Morsi and the Freedom and Justice Party further antagonized various political forces without being able to present a model that could organize a new project it was easy for his opponents to challenge him in June 2013. First civil society organizations and then the military challenged the legitimacy of his rule and by the end of June it was clear that Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood was struggling for its immediate political life. They were under attack from both below and above and had only their ability to mobilize parts of the population physically to protect the president and the places/houses where the power of the Brotherhood was physically located. However, this did not deter the military and on the 3rd of July, Morsi was supplanted by a military take-over. The military replaced the Morsi government by a quasi-civilian government that was totally dependent of the support of the military. It managed to persuade El-Baradei to accept the post as secretary of Foreign Affairs for a while but as soon as it became clear that the Brotherhood would not accept the Coup without resistance and a series of confrontations ended with casualties, he left the government. The military had some success in rounding up the resistance and by October 2013 it had restored order by a combination of support from various groups antagonized by the Brotherhood, violence and detentions of several hundred leaders and activists from The Muslim Brotherhood and the Freedom and Justice Party. In October, the Brotherhood was declared illegal by a court and its means confiscated. It is much too early to state that the Brotherhood have given up the struggle. It was founded more than eighty years ago and has for much of its lifetime been under attack from various governments. It is most likely that it will survive as an underground movement and prepare itself for some kind of political comeback under a new name and with new people in the front. The existing structure and the organization of the Brotherhood have been destroyed but it is reasonable to think that it is a vibrant as a political movement as ever. 12 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 The Muslim brotherhood on one side and the military and its allies in the state bureaucracies on the other constitute the old elites from the Cold War. However, there are also new actors on the stage that have tried to achieve influence. The displaced President Mubarak’s vision was to make his son Gamal the informal leader of the new capitalist class that was being developed in Egypt during his last years as ruler. Had Gamal had more time he might have developed a new ruling system based on economic power in a private (and privatizing public) sector which might have tried to democratize the country from above in concert with US. However, the capitalist class lost most of its influence and it did not achieve any visible role in the transition phase so far. The political developments in 2011 effectively stopped those plans. Instead the military and elite based on the state had some of their authority restored in relation to interests based on private owner- and leadership. They used this position to gradually and tentatively let the brotherhood take over state power through elections. As argued, the Brotherhood crossed more lines that the military was willing to accept and in addition to crushing the structures of capitalist power in 2011 in 2013 it also destroyed the formal structures of Brotherhood power. The military thus prevented the development of the old ideological counter elite and the state independent economic class elite. However, there is still one (potential) elite not seriously engaged by the military. It is the new liberal democratic movements which have been prime movers in political demonstrations in 2011 and in 2013. They are mobilized from the educated and globalized middle classes. Today this group is composed of young people who grew up during the New World Order. They were not entirely socialized into the old conflict between of Mubarak/military and the Brotherhood. They are also independent of the liberal democratic part of the old elite who regarded people like El-Baradei as their leaders and their political perspective was gradual democratization from positions within the old state. This new center-left is together with the Salafists the most important parts of the military’s civil base in the present period. The military and the liberal model The military has pursued the ‘liberal’ path but it has not itself been explicit about its arguments. It is, however, possible to point to three incentives for its strategy. First, the military’s preference for the liberal path could be that it has been used by the democratizations in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is thus ‘authorized’ by the US as the ideal model for 13 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 democratization in the Greater Middle East after 2001. The military is thus able to achieve legitimacy in the eyes of the US. At the same time this procedure might provide legitimacy in the EU which in the long term will be useful for the development of the Egyptian economy. Second, the military will maximize control with the process leading to a new constitution. After the displacement of the Morsi leadership and the take-over of the quasi military government there is no actors that are effectively able to stop the military from running the process towards a new constitution compatible with liberal democratic ideals. Furthermore, the military will be provided with the necessary means to intervene in politics in case of threats to its position or its road map and prevent the constitution from comprising too many Islamist or nationalist ideas. Third, the model may prevent a strong parliament or president from intervening in the development of the constitution on the basis of a popular legitimacy gained by victories in elections. The three incentives all point in the same direction: namely that the military is trying to control the potentially labile process of transition in order to create a constitutional foundation for an on-going process of democratization. The military and the brotherhood: take out the strongest enemy first The military’s harsh attacks on the Brotherhood may also be explained within this understanding, as it possibilities to manage a development towards formal democracy is improved if the opponents that supports the alternative (democratic) path are weakened. Immediately after the displacement of Mubarak the Muslim Brotherhood was the strongest potential opponent of the military. It had the best organization and it had the possibility of placing some of its people on central posts. Its strength was demonstrated by the fact that it had been on the winning side of every national election and referendum after 2011. To weaken the Brotherhood would therefore be one of the most important tasks for the military. The events from the 3rd of July until the 30th of September revealed the military’s focus on this task. The Brotherhood has been beaten by formal actions taken by the military and in streets where it tried to confront the military after it lost its presence in the formal institutions. The brotherhood was beaten in the streets because the tactics it used (demonstrations and occupations of squares) did not gain enough popular support to stop the military and police forces from clearing the areas. The military tactics involved use of intensive violence and was costly in terms of loss of legitimacy but it proved to be an effective means to restore order in Cairo and other major cities. At the same time price of loosing legitimacy was lowered as the brotherhood 14 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 was not politically popular in all sectors of society and because there was a popular support for ‘order’ in an abstract sense (just any order that would allow life, work and education to carry on). A large section of the population apparently supported the crackdown on the Brotherhood’s tactics after the ousting. It should be mentioned though, that the military tactics was expensive seen from the viewpoint of external (international) legitimacy. The following efforts of the military were directed at weakening the organization of the Brotherhood. This was done by jailing and detaining hundreds of its leaders and by letting the political/juridical system starting trials and research into the conduct of leading members. In the end the official status of the Brotherhood as a civil organization was challenged and its and its affiliated organizations was made illegal. The crackdown weakened the Brotherhood’s ability to make a political difference in the coming years struggle about political power and the formation of new institutions. Although the Brotherhood is still an important political movement, it has been seriously weakened, and thus the strongest opponent of the military has been hit hardest in the aftermath of July 2013. The Salafists have not been directly involved in any trial of strength with military. They have so far accepted the military as the leading power in Egypt politics and even if their affiliation with the military strategy is determined by the relations of strength (and animosity towards the Brotherhood) more than a common sense of direction (and thus is likely to change if democratization takes roots) they are at the moment no threat to the military and its strategy. The liberal opposition has also been pacified. In the spring of 2013, it tried to form an alliance with the Brotherhood through an offer of a common roadmap towards democratization. This support was presumably perceived by the Brotherhood as an offer of a tactical alliance, meaning an alliance that was only meant to last until better times where democracy was more firmly rooted and the real struggle for power within a democratic framework could begin. However, El Baradei’s acceptance of the post as Foreign Secretary in the original post-Morsi government reflected that the group’s approaches were mainly tactical. It willingly accepted a central post in Mansour’s government. In this critical situation, El-Baradei sided with the military rather than with the Brotherhood. He later left the government arguing that he personally did not want to lend his name to the killings of Egyptians in domestic political struggles. This series of events showed those liberals who considered El-Baradei their leader that their positions were very unstable. They apparently did not agree on a policy for their participation in the transition 15 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 process. They are thus to be considered a weak part in the current power struggles and no real threat to the military. By the 30th of September, 2013, the military thus seemed – to be the political actor with the most coherent and powerful position. It had pacified and scattered the inner opposition and managed to get at least some accept of their take-over by the international community. In terms of support in the Middle East, their support came mainly from the conservative Gulf States which are trying to counter Islamic opposition groups like the Muslim Brotherhood (Spyer, 2013). The relationship between the military and the liberal groups will probably determine the future of a possible democratization of Egypt. If the military can form and maintain an alliance with this group it will have a platform for democratization progress within limits defined by the military. There is also another possibility for a democratic development. It will in the long run give the best results measured by liberal democratic standards although it will be harder to accomplish. The alternative is an alliance of all the civil parties against the military. The precondition is that they abandon their internal rivalries and confront the military in a united movement in order to create a tipping point, where ‘society’ takes control over the state. However, currently the civil forces – except for the Brotherhood – seem to prefer an alliance with the military. The civil elites have only the last choice if they want to finally get rid of the risk of displacement, supplantment and blackmail from the military in politics. Only in this way can they gather support from the US and the EU for a showdown with the military. The US and the EU could hardly support the military in a confrontation with a united civil coalition. In addition, the parties could gather support from most sectors of the population in a trial of strength between their representatives and an isolated military6. The last solution has its pros and cons. The first pro is that without this showdown the military will be able to continue to control the political process towards democratization without real checks and balances. To the military, such a coalition comprises the risk that its influence may be subordinated ‘objective civil control’. This will enable the civil actors to engage in a democratization process from below. Against this strategy of a united civil society stands that it will be difficult to remain united. It might be possible to unite the parties and movements in an initial series of demands that 6 This strategy is proposed by Robert Springborg, forthcoming. It it also a populist strategy but this time turned against the military, not orchestrated by it. 16 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 the military gives up its central position. The coalition, however, might face a tough answer from the military that will challenge its unity. There will be great gains to the first civil actors that break the ranks, while the rest will become big losers. Therefore this strategy is not very likely to succeed. The most likely outcome is therefore that the military will maintain its position as the primary democracy manager. This implies that it has the most important say concerning the model of democracy to prevailing in the process. This also implies that the most likely outcome is that Egypt during the years to come will develop according to a model that takes its departure in the liberal dimension of liberal democracy (the rule of law and a clear demarcation of realms of authority – including the realm of the military). Morsi’s policy to develop the democratic dimension and rely on popular legitimacy has lost terrain. Therefore: unless the military breaks its alliance with the US and goes for a direct military rule, the stepwise state controlled way to democracy is the most likely. The liberal democratic wing in Egyptian politics thus has to accept the military’s agenda as long as they cannot persuade the Brotherhood to join the rest of the civil actors in an alliance directly turned against the military and based on liberal democratic and secular demands. Since the brotherhoods demands are based on a combination of democratic and religious demands this would almost equal an abandonment of their political identity and antagonizing their social base. This is not likely and therefore – at least in the short term – the alliance between liberals and the military is the most likely force that will write the political liturgy for Egypt. Under these circumstances the military may play a role similar to that played by the military in Turkey during the Cold War. Conclusions The period from January 2011 to September 2013 in Egyptian politics has been analyzed in the framework of the socialization thesis and the concept of democracy management. The question was whether the events, particularly the ousting of President Mohammad Morsi in Juli 2013, have challenged the conception of the Egyptian military as a democracy manager as proposed by the socialization thesis. The preliminary answer is that the process of democratization in Egypt through a democratic process has failed so far but that this does not imply that the process as such has failed. 17 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 There are different ways to democratization and the military has proposed a liberal way similar to that in Afghanistan and Iraq. The first period of democratization in Egypt was characterized by elections without a clearly defined (liberal democratic) institutional framework. This process produced a parliament without proper institutional foundation that thus ceased to function and a presidency that fared only a little better institutionally but which grew increasingly unpopular and towards the end faced demonstrations from below organized by young liberals, a low standing in polls, and hostility from the military. In the end, in July 2013, the military displaced the president and put in a new quasi military government. In the aftermath of this process, the Muslim Brotherhoods various strongholds in the Egyptian society was crushed with means that included extended use of military violence, imprisonment and dissolution of its core organization affiliates as The Freedom and Justice Party. By September 30 2013 the military had control over Egypt and were formally able to impose its own political and institutional model on the society. The first period of the Egyptian democratic experiment thus ended with a defeat for the democratic way to democratization that the leading opposition actor, the Muslim Brotherhood, had promoted. Does this mean that the process of democratization in Egypt is over and that the concept of democracy management in the sense proposed by the socialization thesis is proved invalid? Not yet. It has been demonstrated that the military has a political strategy and that it has had the will to crush its main opponent in order to carry this strategy through. With the destruction of the organization of its main contender, the military has removed the most important barrier to its own model. After this it will be possible for the military to pursue its own reform agenda. The political system in Egypt still has four main characters: The military, which is the strongest, the Salafists, who currently constitute its most ardent supporters, the liberals who to some extent supports the military and finally the Muslim Brotherhood which opposes the military but which is reduced to a movement with a very limited room for maneuver and a leadership which is mainly under the physical control of the military. With the creation of this political landscape it seems that the military has got the necessary means to enforce its preferred model of democratization, the liberal, on the Egypt society. The question will be how much legitimacy the model will get. 18 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 The conclusion is that the period from March 2011 to June 2013 was characterized by a democratic approach to democratization in Egypt and that this particular period has come to an end. In the period from July 2013 to October 2013 a military political campaign ensured that the conditions needed for a change from a democratic to a liberal path to democratization was produced. This approach to democratization including the use of violence to reach democratization is included in the concept of democracy management. Therefore the concept of democracy management as proposed by the socialization thesis is not challenged by the events in Egypt from July to September 30. Whether a liberal model of democratization will be pursued by the military and whether it will be materialized in the years to come is another question. This paper has only assessed the period since the revolt in 2011 to the early autumn 2013 from the perspective of the socialization thesis. This period has added a new set of experiences. This can supply the further development of the thesis with further sensibility to the questions of which models of democracy and democratization the new developments in the Middle East will include. References Albrecht, Holger & Dina Bishara (2011). "Back on Horseback: The Military and Political Transformation in Egypt". Middle East Law and Governance, vol. 3, no. 1-2, pp. 13-23. Hansen, Birthe (2011): Unipolarity and World Politics. London and New York: Routledge. Hansen, Birthe, and Carsten Jensen (eds.) (ftc. 2014): Transforming Arab Civil-Military Relations. New York and London: Routledge. Hansen, Birthe, and Carsten Jensen (2012): Demokrati i Mellemøsten. Copenhagen: Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forlag. Henry, Clement N, and Robert Springborg (2001; 2010): Globalization and the Politics of Development in the Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Huntington, Samuel P. (1991): The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press International Crisis Group. (2012). "Lost in Transition: The World According to Egypt’s SCAF". ICG Middle East Report. No.: 121, 24 April 2012. Jensen, Carsten (ed.) (2013): Democracy Managers. Copenhagen: Danish Defence. 19 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 Jensen, Carsten (2011): Soldater og demokratisering. Det egyptiske militærs rolle og retning efter det arabiske forår. København: Forsvarsakademiets Forlag. Kandil, Hazem (2012): Soldiers, Spies, and Statesmen – Egypt’s Road to Revolt. London and New York: Verson. Linz, Juan J., and Alfred Stephan (1996): Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press. Lutterbeck, Derek (2011): ‘Arab Uprisings and Armed Forces: Between Openness and Resistance’. DCAF, Geneve: SSR Paper 2. MacPherson, C.B. (1977) The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rubin, Barry, and Thomas A. Keaney (eds.) (2002): Armed Forces in the Middle East. Politics and Strategy. London: Frank Cass. * Newspapers and other sources: Al-Ahram Online (2012) ‘Baradei welcomes end of Egypt’s military rule, warns against presidential superpowers.‘ 13.08. Al-Ahram Weekly (2013) ‘Attitudes in post-Morsi Egypt.’ 14-08. ”, ’Morsi retires Egypts top army leaders; amends 2011 Constitutional Declaration; Appoints vice president.’13.08. Arab American Institute (2013)After Tahrir: Egyptian Attitudes Towards Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. www.aaiusa.org. 20-08.2013. CNN.COM (2012) Ahmed Shafik: Egypts ’counter-revolutionary candidate’. 23.05. Dr.dk (2013) ’Egypten opløser Det Muslimske Broderskab.’ 06.09. El-Sisi, Abdelfattah Said, (2006) Democracy in the Middle East. Paper for seminar, political science, Staff Course. Download for scribdassets.com. 25.08.2013. OBS: Writer not confirmed. The Guardian (2012) ‘Egypt Confirms Mohammed Morsi and Ahmed SWhafiq Election runoff’ 29.05. Hussain, Walla (2013) Nour Party: Don’t Blame Islamists for Brotherhoods Mistakes. AL-Monitor, 14.10. 20 The Egyptian Military Birthe Hansen & Carsten Jensen 201013 (www.)ikhwanmirs.net (2012) ‘Egypt’s National Front Meets to Support True Partnership with Presidential Institution.’ 28.06 Reuters (2013) ‘Egypt army plan would scrap constitution, parliament’, 02.07 Sabry, Bassem (2013) Problems Lie Ahead for Egypt Constitution Debate. Al-Monitor, 30.09. 21