NERUDA SONGS THESIS - Ideals

advertisement

Only Changing Lands and Changing Lips:

Life and love in Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs

by

Bethany B. Stiles

An thesis submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Musical Arts

(Voice Performance and Literature)

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

2014

Doctoral Committee:

Associate Professor Dawn Harris, Chair

Associate Professor Gayle Magee, Research Advisor

Associate Professor Stephen Taylor

Associate Professor Barrington Coleman

1

Table of Contents

I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………...3

II. Biographical Information: Peter Lieberson…………………………………………….4

III. Biographical Information: Lorraine Hunt Lieberson…………………………………10

IV. Evolution of Peter Lieberson’s Vocal Style…………………………………………..13

V. Genesis of Neruda Songs………………………………………………………………18

VI. The Grawemeyer Award……………………………………………………………....21

VII. Drawing Comparisons………………………………………………………………...23

VIII. Issues of Text………………………………………………………………………...26

IX. Points for Consideration……………………………………………………………….28

X. Interpretation……………………………………………………………………………29

XI. The Songs………………………………………………………………………………31

XII. Legacy………………………………………………………………..……………..…47

XIII. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………51

Appendix A: Text and Translations…………………………………………………………52

Appendix B: Form and commentary……………………………………………………..…56

Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………60

2

Only Changing Lands and Changing Lips:

Love and Life in Peter Lieberson’s Neruda Songs

INTRODUCTION

Neruda Songs (2005) came to my attention during graduate work at the University of

Louisville, where the cycle had won the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for Music Competition

in 2008. I walked the long hallway featuring photographs of each year’s recipients hundreds of

times, and found myself lingering in front of Peter Lieberson’s picture. As both a mezzosoprano and admirer of Pablo Neruda’s poetry, I was at once intrigued by Neruda Songs. As I

began to research the work, I learned that the cycle is markedly different from the bulk of the

composer's output, as is its companion cycle, Songs of Love and Sorrow (2010). The former was

written for the composer's late wife, acclaimed mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, and the

latter following her death from breast cancer in 2006. It is impossible to discuss Neruda Songs

without examining Lieberson’s romantic relationship with Hunt. Her musical influence, his wide

variety of interests and inspirations, and his willingness to expose his personal life in his music

culminated in these two song cycles, which were among the last large pieces he wrote before his

own death from lymphoma in 2011.

This paper examines Peter Lieberson's award-winning song cycle Neruda Songs (2006)

for mezzo-soprano and orchestra, and the remarkable series of events that made it possible.

Though Lieberson has received many accolades for his instrumental works within the classical

music world, his vocal works have remained somewhat obscure. Following biographical

information, I will discuss the evolution of Lieberson’s vocal writing beginning with Three

Songs (1981) through the last years of his life, including how the major influences of twelve-tone

technique and Buddhism influenced his work. Within Neruda Songs, I will discuss the

3

following: genesis, conception, fruition, text selection, premiere, receiving the Grawemeyer

Award, and the lasting legacy the cycle has had on singers and audiences.

Contemporary vocal music has a reputation for being inaccessible and unnecessarily

difficult.1 Students who wish to sing this music find themselves stranded between the classical

vocal techniques they have learned so diligently and the extended techniques found in some

modern music. As does any style or period, contemporary music contains works than span a

wide range of technical difficulty. Lieberson began his career writing predominantly twelvetone music (very little of which was vocal), but ended his career with an outpouring of vocal

works that teem with lyricism and close attention to vocal contour without sacrificing technical

precision. For this reason, Neruda Songs is attractive to singers wishing to champion the music

of contemporary composers. The emotional transparency of the cycle, with so much raw

emotion bound up in the rich harmonies and lyrical vocal lines, makes Neruda Songs a love story

applicable beyond the two people involved in their original conception. This paper examines

how and why the cycle came to be, the popularity it achieved, and the lasting impact it has had

on the world of contemporary vocal music.

PETER LIEBERSON

Peter Lieberson was born in New York City on October 25, 1946 to famed ballerina and

choreographer Vera Zorina and Goddard Lieberson, music critic and president of Columbia

See Allen Gimbel. “The Pleasure of Modernist Music”, ed. by Arved Ashby. American Record

Guide, 68.4 (July 2005): 292-294.; Melody Baggech. "I Can't Learn That!": Dispelling the

Myths of Contemporary Music.” Journal of Singing - The Official Journal of the National

Association of Teachers of Singing 56.3 (January 2000): 13-22.; Sharon Mabry. “New

Directions: Merging Vocal Styles in Contemporary Music.” Journal of Singing - The Official

Journal of the National Association of Teachers of Singing, 55.1 (September 1998): 43-44.

1

4

Records.2 Through his artistic parents and their support of his musical studies, Lieberson’s

musical talents were nurtured and cultivated. His father’s advocacy of Igor Stravinsky’s work

and willingness to record the music of Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Charles Ives

exposed Peter to this music at an impressionable age.3 When his father told Stravinsky, an old

family friend, of his son’s aspiration to become a composer, Lieberson recalled that the old man

"sat on a couch in the living room with a blanket draped over his legs, drinking milk laced with

scotch ... [and] said, 'It is not enough to want ... you must be!"4

Long before Neruda Songs garnered him the Grawemeyer Award, Lieberson was

recognized as a promising young composer, the first award being The Rapoport Prize in Music in

1972. The following year, he received The Charles Ives Scholarship, made possible by Ives’s

widow Harmony bequeathing the royalties from her husband's music to be used for scholarships

for young composers.5 He received one of two Goddard Lieberson Fellowships in 1984, which

were endowed in 1978 by CBS Foundation in the memory of the Lieberson’s father for his work

as president of CBS Records.6 In 1992, he received The Arts and Letters Award in Music, one

of four prizes given annually to acknowledge a composer as an artist who has arrived at his/her

own voice.7 Additionally, Lieberson was a five-time Pulitzer Prize finalist in Music for the

2

Steven Ledbetter. "Peter Lieberson". Oxford Music Online, n.d. Accessed 9 September 2011. n.

pag. Web.

3

Peter Lieberson, quoted by David Patrick Stearns, “Peter Lieberson obituary”, The Guardian

Online.15 May 2011. Accessed 1 March 2014. n pag. Web

4

Ibid, n. pag.

5

“The Charles Ives Award.” n. d. Accessed 13 April 2014. n. pag. Web.

http://www.artsandletters.org/awards2_popup.php?abbrev=Ives.

6

“The Goddard Lieberson Fellowship.” n. d. Accessed 12 April 2014. n. pag. Web.

http://www.artsandletters.org/awards2_popup.php?abbrev=Lieberson.

7

“The Arts and Letters Award in Music.” n. d. Accessed 12 April 2014. n. pag. Web.

http://www.artsandletters.org/awards2_popup.php?abbrev=Academy%20Music.

5

following: Piano Concerto in 1984, Variations for Violin and Piano in 1996, Rilke Songs 8in

2002, Piano Concerto No. 3 in 2004, and Neruda Songs in 2006.

Having first received a degree in English literature from New York University in 1972,

Lieberson pursued further study in Musical Composition at Columbia University, earning a MA

in 1974. The integration of the voice into his earliest works was minimal, and either

experimental or Sprechstimme. Immersed in the study of twelve-tone methodology, he recalled

that he felt he was "living a Spartan lifestyle,” one that was "hermetic, sealed, and self-secret.”9

His twelve-tone writing received great acclaim in music circles - a performance of his Variations

for solo flute by the Group for Contemporary Music (1972) led to commissions and

performances from, among others, Speculum Musicae, Oppens, Fred Sherry and Tashi. 10 Most of

his writing at Columbia University featured chamber ensembles, such as Concerto for Four

Groups of Instruments (1972), Concerto for Violoncello with Accompanying Trios (1974), and

Accordance (1975) for eight instruments and chamber ensemble.11

Many of Lieberson’s teachers, including Milton Babbit, Donald Martino, and Charles

Wuorinen, grew into musical maturity in the 1950s-60s, and had been directly influenced by the

influx of ultra-modern composers such as Ernst Krenek, Stefan Wolpe, and Hanns Eisler, who

immigrated to the United States in the 1930s to escape the rise of the Third Reich and ensuing

World War II.12 The 1970s saw the rise of electronic and popular music, though some

“Peter Lieberson”. The Pulitzer Prizes Online. n. d. Accessed 11 April 2014. n. pag. Web.

http://www.pulitzer.org/faceted_search/results/lieberson%2C+peter.

9

Peter Lieberson, "Concept Becomes Experience: A Composer's Journey." The Shambhala Sun,

May 1997. n. pag. Web.

10

Ledbetter, n. pag.

11

“Peter Lieberson.” n. d. Accessed 31 March 2014. n. pag. Web.

http://www.pytheasmusic.org/lieberson.html.

12

Joseph N. Straus, “A Revisionist History of Twelve-Tone Serialism in American Music.”

Journal of the Society for American Music 2:3 (2008), 355.

8

6

composers, Elliot Carter and Ralph Shapey among them, were still attempting to find new and

inventive methods by which to integrate twelve-tone methods into their music.13 Of this era in

composition, brought about by the expansion of Arnold Schoenberg's principles, Lieberson said,

Not all composers were suited to this kind of thinking, but those who were not were made

to feel irrelevant. For the rest of us, this was clearly the path of the future. What was

daunting, however, was the complexity of method. I would erect theoretical edifices

capable of housing multiples of the twelve-minute piece I was working on. The

possibilities were endless: the relationships within one set of notes could be extended to

aggregates of sets and further expanded to multiple arrays of sets. Then one had to realize

all this stuff as music, for performers who needed time to breathe or draw a bow across a

string.14

Yet throughout his career, Lieberson's music has been praised for its color and vibrancy, which

the composer credits partially to his upbringing in such close proximity to the New York jazz

culture and exposure to musicals such as My Fair Lady (1964) and The Sound of Music (1965),

works in which his father had both professional and personal interest through his work with

CBS.15 With the premiere of his Piano Concerto (1983), composed for Peter Serkin and

commissioned by Seiji Ozawa and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) for their centennial,

Lieberson established himself as a promising young composer – as evidenced by the fact that the

concerto was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the recipient of Opus Magazine’s Contemporary

Music Award in 1985.16 In addition to his associations with other major orchestras such in New

York, Cleveland, Chicago and Los Angeles, Lieberson enjoyed long-standing artistic

Ibid, 356.

Lieberson, Shambhala Sun, n. pag.

15

Peter Lieberson. Interview by Frank J. Oteri. "Peter Lieberson's Neruda Songs Wins 2008

Grawemeyer." New Music Box, 2 December 2007. Web. 12 June 2013. n.pag.

16

“Peter Lieberson”. Composer long biography courtesy of G. Schirmer Online:

http://www.musicsalesclassical.com/composer/long-bio/Peter-Lieberson. Web. n.d., n. pag.

13

14

7

collaborations with Serkin, Yo-Yo Ma, Emanuel Ax and Oliver Knussen.17 He wrote with a rare

combination of modernistic rigor and Romantic sensuality, the latter coming ever more to the

forefront in his later years.18

Running parallel to the musical influences in his life were those of Tibetan Buddhism.

Upon completion of his studies at Columbia University in 1976, he moved to Boulder, Colorado

to study with Chögyam Trungpa, a Tibetan Vajrayan Buddhist master he had met two years

earlier. It was there he befriended and later married Ellen Kearney, a fellow student of Trungpa.

At their instructor's request, the couple moved to Boston, where they founded and became codirectors of a meditation and cultural program. During this period, Lieberson also earned a Ph.D.

from Brandeis University. He had a teaching position at Harvard University from 1984-88, but

resigned this post to become international director of Shambhala Training in Halifax, Nova

Scotia.19 Another notable student of Trungpa’s, Pema Chödrön, was an American school teacher

before she began to study Buddhism. Based at the same school in Canada, today she is an

ordained Buddhist nun and renowned public speaker. The influence of Trungpa’s teaching on

Lieberson’s music was deep and lasting.

The year 1997 was one of great personal and professional growth for Lieberson. His

spiritualism inspired many of his compositions, including Ashoka's Dream (1997), which would

unite him with his future wife and artistic collaborator, Lorraine Hunt. Lieberson's musical style,

which since the beginning of his relationship with Hunt Lieberson had broadened to incorporate

a richer harmonic vocabulary along with a heightened awareness of the importance of melody,

“Peter Lieberson”. Composer short biography courtesy of G. Schirmer Online:

http://www.musicsalesclassical.com/composer/short-bio/Peter-Lieberson. Web. n.d., n.pag.

18

Alex Ross. "The Rest is Noise". Personal blog entry by author, 23 April 2011. Web. 31 May

2012. n. pag

19

Ledbetter, n. pag.

17

8

reached a new level of lyric and dramatic intensity in Neruda Songs.20 Of that time in his life,

he noted:

I think really when I met Lorraine, it was quite an amazing time in my life. I had just had

come toward expressing something that was very personal, and hopefully more universal,

too, because it was a story about a transformation that a human being underwent. Meeting

Lorraine, was who such an intuitive musician, such a powerful presence, so unafraid of

her emotions, so able to access those emotions and express them, a person who could

hold the space on stage in a way I'd never seen before. There was no artifice.21

The couple was married in 1999, the union proving fruitful with regard to artistic

collaboration. His wife’s influence on his vocal writing catapulted Lieberson’s music into the

realm of accessible contemporary vocal music. After her death, he married long-time friend and

former Buddhist nun Rinchen Lhamo, who would become his caretaker and companion in the

last years of his life. He was diagnosed with lymphoma shortly after Hunt Lieberson's death in

2006, of which he said, “I’d been sick taking care of Lorraine, but didn’t get myself checked

out.”22 The couple then moved to Houston where he continued treatment while composing.

Among his last compositions were: The Coming of Light (2009) a commission by Unity Temple

Restoration Foundation and The Chicago Chamber Musicians together with Winsor Music, Inc.

to honor of the 2009 centennial of the dedication of Unity Temple, Frank Lloyd Wright's

modern masterpiece, which was a six-movement chamber work using texts of John Ashbery,

William Shakespeare, and Mark Strand; Songs of Love and Sorrow(2010), another commission

by James Levin and the Boston Symphony Orchestra with texts by Pablo Neruda; and a

commission of the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, D.C. through a gift from the

20

Stephen Eddins. Rev. of Neruda Songs, by Peter Lieberson/Lorraine Hunt Lieberson/James

Levine & The Boston Symphony Orchestra. All Music Online, n.d., n. pag. Web.

21

Oteri, n. pag.

22

Peter Lieberson, interview by Pierre Ruhe. "R.I.P. Peter Lieberson: The composer in

conversation before the ASO performed 'Neruda Songs’.” Arts Atlanta Online. 24 April 2011.

Accessed 31 May 2012. n. pag. Web.

9

John and June Hechinger Commissioning Fund for New Orchestral Works entitled Remembering

JFK: An American Elegy (2010) for narrator and orchestra, in which Lieberson used excerpts

from three different speeches given by President John F. Kennedy between the years 19611963.23 In a review written towards the end of Lieberson's career, music critic Allan Kozinn

discussed the plethora of elements from which the composer drew inspiration, saying,

When Peter Lieberson began composing in the early 1970s, his compositional hero was

Stravinsky in his late acerbic style, and his teachers included Milton Babbitt and Charles

Wuorinen. But he was also fond of musical theater, Minimalism and jazz; before he

studied composition formally, he learned about harmony by figuring out the voicings on

recordings by the jazz pianist Bill Evans. Mr. Lieberson’s works meld most of those

influences into a cohesive, energetic and intensely communicative style, with brainy,

atonal surfaces that attest to his post-tonal pedigree and a current of lyricism and drama

that gives this music its warmth and passion.24

On April 23, 2011, Lieberson died at the age of sixty-four in Tel Aviv, Israel from

leukemia, a complication from the treatment of lymphoma. He was survived by Lhamo and his

three children from his first marriage.

LORRAINE HUNT LIEBERSON

Lorraine Hunt Lorraine Hunt was born on March 1, 1954 in San Francisco to parents who

were deeply invested not only in the performance of music, but also in its teaching. Her father,

Randolph Hunt, taught and conducted community ensembles and operas, while her mother

Marcia, a contralto, performed and taught vocal music. Hunt studied piano and violin in her

youth, before switching to viola performance, in which she took her degree at San Jose State

University. She became a freelance musician in the Bay Area, before a love interest inspired her

“Peter Lieberson – works”. Courtesy of G. Schirmer Online:

http://www.musicsalesclassical.com/composer/work/44968. n.d. Web. Accessed 22 September

2013.

24

Allan Kozinn. ”Composer Portraits – Peter Lieberson: Portrait Reveals a Collage of

Influences”. The New York Times, 29 September 2009. Web. n. pag.

23

10

to move to Boston, Massachusetts.25 The diligent Hunt also studied voice at Boston

Conservatory during that time, and at the age of twenty-six, decided to devote more time to voice

performance. Her breakthrough came in 1985, when she appeared as Sesto in Händel's Guilio

Cesare, under the direction of Peter Sellars at the Summerfare Festival in Purchase, New York.

Though Sellars' interpretation was highly controversial—setting the story in the contemporary

Middle East, portraying Sesto as an armed terrorist with an Uzi—Hunt's performance received

stellar reviews and she was touted as a promising young star.26 The ever self-effacing Hunt

maintained a low profile while continuing to receive job offers from major companies such as

Glyndebourne, Opéra de Lyon, and the Berliner Philharmoniker.27

Hunt's superb artistry and well-developed technique enabled her to portray a diverse array

of characters from across the period spectrum. The first decade of her professional career was

dominated by Baroque opera, for which she received many accolades, thanks to the ease with

which she negotiated florid passages and ornamentation.28 Ever versatile, Hunt was a champion

of contemporary music well before she met Lieberson. The first met in 1997, when she was

selected to premiere the role of Triraksha in Lieberson’s Ashoka’s Dream, the story of an Indian

emperor in the third century B.C. who renounced violence following his conversion to

Buddhism. Though Lieberson was married with three daughters at the time, the chemistry

between the two would not be denied. Following his divorce from Kearney, Lieberson and Hunt

25

"Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson". Bach Cantatas Website. http://www.bach-cantatas.com/Bio/Hunt

Lorraine.htm. 29 August 2013. Web, 12 June 2013, n. pag.

26

Ibid, n. pag

27

Ibid, n. pag.

28

See Martin Bernheimer. "Lorraine Hunt Lieberson."Opera News 68: 5 (2003), 60. Music

Index, EBSCOhost (accessed March 17, 2014); R. Moore.. "Lorraine Hunt Lieberson: Ravinia

Recital." American Record Guide 72:3 (2009),202-203. Music Index, EBSCOhost (accessed

March 17, 2014).; Gregory Berg. "Lorraine Hunt Lieberson: Handel Arias." Journal of Singing

63:2 (2006), 239-240. Music Index, EBSCOhost (accessed March 17, 2014).

11

married in 1999. Thus began a romantic and creative partnership that would endure until her

untimely death in July of 2006. During her career, Hunt Lieberson remained an active performer,

singing a variety of works ranging from Handel’s Theodora at Glyndebourne in 1996 to Britten’s

The Rape of Lucretia at the Edinburgh Festival in 1999.29 Though noted for her ability to

perform Baroque music, Hunt Lieberson remained dedicated to furthering contemporary

composition, premiering the role of Myrtle Wilson in John Harbison’s The Great Gatsby (1999)

and John Adams’s 2000 nativity oratorio El Niño at the Théaâtre de Châtelet in Paris, as well as

her husband’s song cycle Rilke Songs (1999).30

An intensely private person, it is unknown exactly when Hunt Lieberson received her

diagnosis, but it was certainly by 2005. Early in that year, she once again partnered with Peter

Sellars for a semi-staged recital tour of two of Johann Sebastian Bach cantatas in what proved to

be a tragic foreshadowing of her fate. Wearing a flimsy hospital gown and woolen socks, Hunt

Lieberson performed Bach’s BWV 82 Ich Habe Genung (“I have enough”) as a terminally ill

patient no longer able to endure treatments and yearning for the comfort of Christ. During

performances of the work, Hunt Lieberson—her face contorted with pain and yearning—even

went so far as to yank tubes from her arms while singing Bach’s rich melodies.31 In the last years

of her life, she was forced to cancel many events, including the premiere of Kaija Saariaho’s

opera L’Amour de Loin, which won the Grawemeyer Award for Composition in 2003, five years

before Peter Lieberson’s song cycle would win.32 She was also forced to withdraw from the

world premiere of John Adams’s opera Doctor Atomic (2005) with San Francisco Opera, citing a

29

Alan Blyth. "Lorraine Hunt-Lieberson." Oxford Music Online, n.d. Web. 9 September 2011. n.

pag.

30

Ibid, n. pag.

31

Bach Cantatas website, n. pag.

32

Ibid, n. pag.

12

“back injury” sustained earlier in the year, ultimately replaced by Kristine Jepsen. 33 Her final

professional engagement was the touring production of Neruda Songs with the Boston

Symphony Orchestra in 2006, completed only a few months before she succumbed to breast

cancer at the age of fifty-two.

EVOLUTION OF PETER LIEBERSON’S VOCAL WRITING

Lieberson’s earliest attempt at vocal writing was Three Songs (1981) for soprano and

chamber ensemble. The entire cycle lasts roughly seven minutes and is based on the poetry of

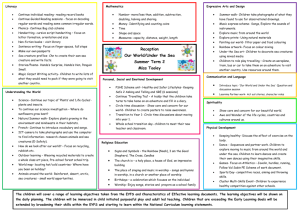

American writer Douglas Penick, a fellow student of Trungpa. Figure 1 contains two excerpts of

the vocal line in“Listen and Hear” from Three Songs, depicting a very different manner of vocal

writing than Lieberson’s later works. In the final measures of examples A and C, the use of text

painting lacks subtlety. In example B, the soprano must cover a wide range in a very short

amount of space. It is difficult to shake the impression that Lieberson’s vocal writing in this

song is based more on compositional strategy – pitch, interval, register, and so on – than on

lyricism or strengths of the vocal apparatus.34 The tessitura in the first two measures of example

C demonstrates the composer’s lack of experience working with the voice. It would be very

difficult to understand words intoned at a piano dynamic at that part of a soprano’s range.

Ben Mattison. “Kristine Jepsen replaces Lorraine Hunt Lieberson in Doctor Atomic.”

Playbill Arts, 19 July 2005. n. pag. Web. http://www.playbillarts.com/news/article/2494.html

34

John C. Levey. Concertino for Flute, Harp, and String Quartet Volume I. Technique and

evolution in Peter Lieberson's Three Songs and "Rilke Songs" Volume II. Diss. University of

Michgan, 2009. Ann Arbor: ProQuest: 72.

33

13

Figure 1. Vocal excerpts from “Listen and Hear” from Three Songs

A)

B)

C)

Additionally, Three Songs demonstrates how separate the idea of singer and ensemble

seemed to be in the composer’s mind. Rather than integrate the soprano’s beginning pitch into

the harmonic fabric of the accompaniment, Lieberson prefers the soprano supply new pitch

material upon entering.35 This cycle does not rank among Lieberson's better-known

compositions, but it dates from a pivotal stage in his career, and more importantly, is emblematic

of his early mature style.36

Three Songs was the sole representative of his song writing for nearly twenty years, until

35

36

Levey, 26.

Ibid, 2.

14

the Rilke Songs of 2001. In between, Lieberson composed only two works that included voice.

The first, King Gesar (1991) was the result of a 1988 commission by German composer Hans

Werner Henze for performance at the Munich Biennial for pianists Peter Serkin, Emanuel Ax,

cellist Yo-Yo Ma. Once again utilizing the text of fellow Buddhist Douglas Penick, Lieberson

described the work as,

A monodrama/opera that tells the story of a legendary Tibetan warrior king, Gesar of

Ling, who rose from obscurity to battle the demons that enslave humankind…conceived

as a kind of campfire opera. I visualized a situation akin to Tibetan “performances”: the

campfire in a pitch black night under the dome of an immense starry sky, or, a

daytime community gathering in a very large tent or small town square—familiar

situations in which people eat, drink, and tell stories.37

In the work, a narrator delivers lines above the orchestration while employing various techniques

to depict distinct characters, none of which are sung with classical technique. But Lieberson’s

faith was influencing his work on a greater scale. Chögyam Trungpa’s influential phrase was

influencing every aspect of his life, including music -“first thought, best thought”, referring to a

state of thought that is fresh, open, and responsive.38

Lieberson’s other work for voice between the years 1981-2001 was Ashoka’s Dream

(1997), his first and only opera. As with King Gesar, the opera reflected Lieberson’s immersion

in his faith – the opera tells the story of Ashoka Maurya, a 3rd-century B.C. king of India and the

only ruler to unify India until the 19th century A.D, focusing on Ashoka’s transformation from

angry, isolated young conqueror to enlightened ruler.39 In it, one could find hints of Lieberson's

later style, as it already espoused the some of the expressive melodicism that Lieberson later

37

Peter Lieberson. King Gesar (notes: Sony Classical 57971, 1991): 1.

Lieberson, Shambhala Sun, n. pag.

39

Short synopsis courtesy of Music Sales Classical, n. d. Accessed 10 March 2014. n. pag.

http://www.musicsalesclassical.com/composer/work/922/30192.

38

15

attributed—almost entirely, in fact—to Hunt Lieberson’s influence.40 Critics noted that while

the music was "adequately tailored to the singers' capabilities," it was ultimately "not memorable

enough to fix their characters in our minds."41 Lieberson's voice writing received mixed reviews

following the opera’s premiere in Santa Fe, though many recognized that a change had occurred,

including critic Virko Baley,

Peter Lieberson's harmonic sound owes much to expressionism and serialism. At the

same time, its clear rhythmic pulse, supported by an overall tonal design, allows his

naturally lyrical side to emerge in many affecting moments. The voice is often permitted

to be the bearer of news (as opposed to the orchestra, which in too many 20th century

operas is placed on the stage and the singers relegated to the pit).42

In 2001, Lieberson published Rilke Songs, a cycle for mezzo-soprano and piano. Lieberson's

settings grew out of a full understanding of his wife's extraordinary vocal and dramatic gifts and

are suffused with his intimate awareness of her personal and artistic vitality, as well as the

fragility of her physical health.43 He wrote of the songs,

I think of them as love songs even though the poems themselves are not overtly about

love. They are about being childlike and open…about the breath being a complete

exchange between our own essence and the universe, how the breath seems to go out into

space like our wandering son; the mysterious way in which we might transform

ourselves: “If drinking is bitter, turn yourself to wine (from ‘Stiller Freund’)” To me

these Rilkean insights are gifts of love.44

It is apparent that a drastic shift in Lieberson’s treatment of the voice had taken place. In Rilke

Songs, a thoughtful and careful crafting of the melodic material seemed to emerge in place of the

seemingly mathematical lines of Three Songs. In Figure 2, example A depicts a vocal line that

40

Levey. 72.

John von Rhein."Interior Opera `Ashoka's Dream' Steeped In Zen, But Fails To Make Deep

Connection With Audience." Rev. of Ashoka's Dream, by Peter Lieberson, Douglas Penick, &

Stephen Wadsworth. Chicago Tribune 29 July 1997: n.pag. Web.

42

Virko Baley. "An Evening of Premieres at Santa Fe". Opera Journal 30/3 (1997), n.pag. Web.

43

Eddins, n. pag.

44

Peter Lieberson, Rilke Songs (notes, Bridge Records 9178, 2006): 3.

41

16

emerges from the harmonic material of the accompaniment, providing greater unification

between soloist and ensemble. In example B, Lieberson treats the singer to a descending

chromatic melodic line that allows for maximum expressivity.

Fig. 2: Treatment of the voice in “O ihr Zärtlichen” from Rilke Songs

A)

B)

Though a softer style had emerged within Ashoka’s Dream, Lieberson credited his wife with the

fascinating transformation of his vocal writing,

In 1997 my life, and my composing life, changed completely when I met my wife,

Lorraine. I can't adequately express how much her intuitive and profoundly musical

approach to performance has affected me. Her instincts are fiery and definite in terms of

what needs to be done to elicit the best performance, whether it concerns how a phrase is

shaped, for example, or what needs to be done in terms of the accompaniment. Rarely is

there an emphasis on vocal technique–the musical outcome is the focus of attention. This

has led many to admire her, and for me, admiration has been accompanied by a deep

gratitude for lessons learned.45

45

Peter Lieberson, Rilke Songs: 1.

17

...Hearing [Lorraine] perform I became more and more aware of the significance of

melodic line and what a great performer can do to invest it with meaning and integrity. I

think it is important to remember that for many composers in the 60s and 70s, melody

was simply regarded as one dimension of the musical space. Vocal lines themselves

were generally treated as an instrumental line, without overdue attention to how the

words were articulated, or to the placement of consonants and vowels in particular

registers, or even to the complexity of the vocal instrument itself.46

GENESIS OF NERUDA SONGS

"I am so grateful for Neruda’s beautiful poetry, for although these poems were written to

another, when I set them I was speaking directly to my own beloved, Lorraine."47

Lieberson's homage to Nobel Prize-winning poet Pablo Neruda (1904-1973), who penned

Cien sonetos de amor, describes the timelessness and transcendence of the lovers' words. Born

Ricardo Eliezer Neftali Reyes y Basoalto, Neruda adopted the pseudonym under which he would

become famous while still in his early teens.48 He was a highly prolific author whose main

subjects were love and eroticism (Veinte Poemas de Amor y una Canción Desesperada, 1924),

metaphysics (Residencia en la tierra, 1933), and politics (Canto General, 1950). 49 He was a

prominent member of the Communist Party in Chile, receiving the nomination for president from

the party in 1971, though he withdrew after reaching an accord with the nominee of the Socialist

Party, Salvador Allende. He was appointed as Chilean Ambassador to France, and while serving

his post in Paris, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.50 His failing health forced him

to resign the post and return to Chile, where he died in 1973 just days after a right-wing political

46

Lieberson, Rilke Songs: 1.

Peter Lieberson and Pablo Neruda. Neruda Songs: For Mezzo-soprano and Piano. New York:

Associated Music Publishers; [2011], c2005. Print.

48

“Pablo Neruda.” Biography courtesy of The Poetry Foundation, n. d. Accessed 9 April 2014.

n. pag. Web.

49

Daniel Party. “Pablo Neruda.” Oxford Music Online, n.d. Accessed 9 April 2014. n. pag.

Web.

50

The Poetry Foundation, n. pag.

47

18

coup killed President Allende and seized the government.51 Though much of his writing is

infused with ideology based upon his revolutionary views of Chilean politics, Neruda is perhaps

best known for the sensuousness and eroticism of his poetry. “Traditionally,” stated Rene de

Costa in The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, “love poetry has equated woman with nature. Neruda took

this established mode of comparison and raised it to a cosmic level, making woman into a

veritable force of the universe.”52

Written and dedicated to his third wife Mathilde Urrutia (1912-1985), Neruda's ravishing

Cien Sonetos de Amor is divided into four parts: Morning, Afternoon, Evening, and Night. Five

sonnets were selected for use in the cycle: "Si no fuera porque tus ojos tienen color de luna...",

"Amor, amor, las nubes a la torre del cielo...", "No estés lejos de mí un solo día, porque cómo...",

"Ya eres mía. Reposa con tu sueño en mi sueño...", and "Amor mío, si muero y tú no mueres....".

The five excerpts deal explicitly with the "joy, sensuality, fusion, ecstasy, and triumph" of love.

The first and second poems are found in the Morning section, the third from Afternoon, and the

final two from Night. From that point on, Peter did not consult with Lorraine while he was

writing the songs, presenting them as a fait accompli. She noted, "We'd been together for a

while, so he was really tuned into my voice. And so I didn't really have to say much at all about

what he had written for me. He was right on, as far as range and technical ease of the vocal

lines."53

It was quite by chance that the love sonnets that so aptly described the Liebersons'

relationship came to be the lyrics of the song cycle. As evidenced by the color of the home she

51

Ibid, n. pag.

“Pablo Neruda.” The Poetry Foundation, n. pag.

53

Jeff Lunden. "Lieberson's 'Neruda Songs', Tracing Love's Arc". National Public Radio:

Weekend Edition Saturday, 30 December 2006. Web. Accessed 12 June 2013. n. pag.

52

19

shared with her husband in Santa Fe, Hunt Lieberson adored the color pink.54 Perhaps it was for

that reason that, while at the Albuquerque airport in 1997, Lieberson’s eye was drawn to the

rose-colored cover of a copy of Neruda’s love poems translated into English by Stephen

Tapscott. "They were so passionate and beautiful and the words were words that I would've

spoken to Lorraine," Lieberson recalled. "And I thought, immediately, on the spot, that I must set

these—at some point— for Lorraine."55

The opportunity came in 2003, when Lieberson received a co-commission from the Los

Angeles and Boston symphonies. Esa-Pekka Salonen, conductor and music director of the LA

Philharmonic and Grawemeyer Award recipient in 2012, originally requested that the

commission result in a concert; Lieberson noted that the concept evolved into a desire to write a

song cycle that his wife could perform. Since she spoke Spanish, Hunt Lieberson would read the

sonnets aloud with her husband and marked the ones she preferred. Lieberson recalled that while

the two did not necessarily agree on which specific poems should be set to music, his wife was

certainly involved in the initial stages of the process.56

Written and dedicated to his beloved, Mathilde Urrutia, Neruda's ravishing Cien Sonetos

de Amor is divided into four parts: Morning, Afternoon, Evening, and Night. Five sonnets were

selected for use in the cycle: "Si no fuera porque tus ojos tienen color de luna...", "Amor, amor,

las nubes a la torre del cielo...", "No estés lejos de mí un solo día, porque cómo...", "Ya eres mía.

Reposa con tu sueño en mi sueño...", and "Amor mío, si muero y tú no mueres....". The five

54

Katherine Boyle. "'Neruda Songs' at the Kennedy Center: A lost love's legacy". The

Washington Post, 27 September 2012. Web. 12 September 2013. n. pag.

55

Lunden, n. pag.

56

Ruhe, n. pag.

20

excerpts deal explicitly with the "joy, sensuality, fusion, ecstasy, and triumph" of love.57 The

first and second poems are found in the Morning section, the third from Afternoon, and the final

two from Night. From that point on, Peter did not consult with Lorraine while he was writing the

songs, presenting them as a fait accompli.58 She told National Public Radio in 2004, "We'd been

together for a while, so he was really tuned into my voice. And so I didn't really have to say

much at all about what he had written for me. He was right on, as far as range and technical ease

of the vocal lines."59

By the time Neruda Songs was published, it seemed as though the two artists were of one

mind, from a creative standpoint. Conductor James Levine, who took the podium for the 2005

premiere with Boston Symphony, called the songs "a kind of miracle," and called attention to

Lieberson's compositional shift from twelve-tone music to the velvety lyricism of Neruda Songs,

noting, "Peter, who has written a great many thorny pieces early on, somehow was inspired to

another kind of music in this piece. These songs, I think, fall in the category of very great and

very accessible, which is a combination almost as rare as the opposite."60

THE GRAWEMEYER AWARD

Neruda Songs has enjoyed great success among academic and general audiences alike.

A major catalyst to its popularity has been through the University of Louisville. Every year, the

university presents the Grawemeyer Awards, which draw nominations from around the world.

In 1983, H. Charles Grawemeyer, a successful entrepreneur and prominent patron of the arts, set

up a $9 million endowment to award distinguished work in the areas of Religion, Psychology,

57

Robert Hilferty, "Concerts Everywhere: New York City - Boston Symphony: Lieberson,

Strauss, Mahler," American Record Guide 69/2 (2006): 29.

58

Lunden, n. pag.

59

Ibid, n. pag.

60

Lunden, n. pag

21

Ideas Improving World Order, Education, and Music Composition. The university's website

notes,

Grawemeyer distinguished the awards by honoring ideas rather than life-long or

publicized personal achievement. He also insisted that the selection process for each of

the five awards--though dominated by professionals--include one step involving a lay

committee knowledgeable in each field. As Grawemeyer saw it, great ideas should be

understandable to someone with general knowledge and not be the private treasure of

academics.61

Today, the annual winner in each category receives a prize of $100,000. The first

Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition was given in 1985 to Witold Lutoslawski for his

Symphony No. 3, chosen from among 204 submissions. Dedicated to promoting higher

education, Mr. Grawemeyer stipulated that the winner of the Composition award must serve a

week-long residency to work with the enrolled composition students at the university. Despite

just having undergone rigorous treatment for cancer, Peter Lieberson fulfilled this duty and

served in residence from April 14-18, 2008. His stay culminated in a lecture featuring the 2006

live recording of Neruda Songs with James Levine, Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, and the BSO.

The international competition boasts entries from around the world, all vying for the

coveted award. Though there have been several American composers besides Lieberson to win

the award (including John Adams, John Corgliano, and Joan Tower), the majority of winners

have been composers outside the United States: Harrison Birtwistle, Gyorgy Ligeti, Krzysztof

Penderecki, and Tan Dun, among others. The 2013 Grawemeyer Award in Music was awarded

to Dutch composer Michel van der Aa for his multimedia cello concerto Up-close, described as a

“highly innovation fusion of musical and visual art.”62

“The Grawemeyer Awards: History.” n.d. The University of Louisville, 2009. n. pag. Web.

Accessed 14 March 2013.

62

“The Grawemeyer Awards: Current Winners.” n. d. The University of Louisville, 2009. n.

pag. Web. Accessed 12 March 2014.

61

22

The judging process is completed in three tiers: the first two are judged by selected

members of academia (theorists, composers, etc.), while the third tier (which ultimately selects

the grand prize winner) is comprised of prominent arts patrons who do not earn their living in the

creative arts—a more "democratic" system, according to Mr. Grawemeyer.63 Professor Marc

Satterwhite, Grawemeyer coordinator and professor of composition at the University of

Louisville, described the first two tiers as, “… looking for pieces which are both "well-made"

technically, and which also have a potential appeal to a general classical music audience.

Academically we are looking for the usual things: a convincing structure, imaginative use of

musical materials, and competent scoring.”64

In 2008, Lieberson's submission Neruda Songs garnered him the coveted prize. His work

was chosen from more than 140 compositions entered from around the world. University of

Louisville composition instructor and director of the awards program, Marc Satterwhite, noted

that, “The piece has beauty and surface simplicity, but great emotional depth and intellectual

rigor as well." Lieberson himself took an especial pride in this particular award, noting,

I have to say I never really concern myself too much with prizes, awards, and so on. But

this one is meaningful to me precisely because it is for the Neruda Songs and because of

the kind of panels that are involved for the Grawemeyer. There are lay people, so to

speak, involved, too. It's such a meaningful piece to me, so it's very nice that the prize

was awarded to it.65

DRAWING COMPARISONS

Neruda Songs has been compared to many other song cycles in terms of mood, purpose,

and style. As Peter Lieberson presented the cycle as a gift to his beloved, it calls to mind Robert

“The Grawemeyer Awards: Background.” n.d. The University of Louisville, 2009. n. pag.

Web. Accessed 12 March 2014.

64

Satterwhite, Marc. Personal interview. 28 March 2014.

65

Lieberson, interviewed by Oteri, n. pag.

63

23

Schumann’s Frauenliebe und –Leben (1840), set to poetry by Adelbert von Chamisso. The

sentiments of both cycles depict the arched form of love as seen through the eyes of a woman.

But whereas Chamisso's words depict a younger, more innocent, and somewhat reserved portrait

of the relationship, Neruda’s poetry is of a decidedly more sensual, sexual nature.

Important musical differences also exist between the two works. For example, while

Schumann’s cycle comes full circle (with the piano closing the cycle with the singer’s original

melodic material in the original key), Lieberson's last movement finds the singer and

accompaniment of equal importance outlining a G major triad, gently fading away into the

tranquility of two lovers who have said all they could to one another and find closure in having

done so. In this way, Neruda Songs more closely resembles the closing bars of Gustav Mahler’s

Das Lied von der Erde (1908-09), wherein the tide of Der Abschied recedes peacefully on the

word “ewig” (forever), without ever fully resolving to a cadence. Written after a year of

devastating personal issues, Das Lied is considered somewhat of an opus ultimum, a concept

long honored and respected by critics and historians as the final work which formally brings the

composer's career to a conclusion.66 Though Lieberson did not yet know he was ill, his wife’s

cancer had progressed to the point of her canceling almost every other engagement except

Neruda Songs. Perhaps Lieberson’s beautiful, lyrical cycle was to be his wife’s opus ultimum,

the crowning achievement to a diverse and spectacular career, even if that was not its original

intent.

For that reason, Neruda Songs is often likened to Richard Strauss's Vier Letzte Lieder

(1948), his opus ultimum that was apparently planned and executed as such.67 The Lieder

66

Aubrey S. Garlington. Richard Strauss's "Vier letzte Lieder": The Ultimate "opus ultimum".

The Musical Quarterly 73:1 (1989), 79.

67

Ibid, 80.

24

occupy an analogous place in the final years of German Romanticism,68 the lushness and

decadence of which Lieberson incorporated in Neruda Songs. Though he would compose other

works after this cycle, Neruda Songs was the full bloom of Lieberson’s final and more lyrical

compositional period. In addition to being a celebration of their marriage, the songs may also

have been a cathartic, restorative experience for both Peter and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson as they

approached the end of their time together.

One of Lieberson's most decorated compositions, the cycle won the 2008 Grawemeyer

Award for Music Composition, and the first recording, a live performance under Levine,

received three Grammy nominations, including one for the music itself.69 While such awards do

not necessarily guarantee a long programming life for a work, Neruda Songs has garnered quite a

following in recent years and has become a favorite among popular audiences. Sarah Connolly

gave the European premiere in London, and Kelley O'Connor has sung the music with a number

of orchestras.70 The heartbreaking circumstances surrounding Lieberson's works for his wife had

previously resulted in singers perceiving them to be “off limits" in the sense that the songs

belong to Hunt Lieberson, and that further performances might be considered disrespectful to her

memory.71 Although the songs were so integrally related to the person for whom they were

written, Lieberson expressed his feelings regarding other soloists taking up the cycle, saying, "I

think it might be more difficult for the singer than for me. I don’t think Lorraine would have

wanted them to be only her province. Even if she were alive today, I don’t think she would want

68

Ibid.

William R. Braun, “LIEBERSON: Neruda Songs and THEOFANIDIS: Symphony No. 1”.

Opera News, V. 76, No. 5 (2011), n.pag. Web

70

Braun, n.pag.

71

Kelton, 258.

69

25

that. She’d want other singers to sing them, I know she would."72 O'Connor, chosen to perform

the songs with the Chicago Symphony, contacted Lieberson prior to the performance to ask if he

would be willing to work with her, and he invited her to Hawaii where he was staying with his

family.73 It was there that Lieberson worked with the young mezzo, and gave his blessing to her

performance.74

The allure of Neruda Songs seems to be the result an obsession with the deeply sensual,

ultimately tragic love story behind them. All five songs begin with a strikingly low pitch,

imparting a particular weight to the cycle.75 The cycle also happens to be some of the

composer's most accessible and aesthetically pleasing work. In discussing the appeal of the

songs, art journal critic Robert Hilferty said, “[Lieberson] has never been so lyrical. [Neruda

Songs] is a ravishing work, saturated with love. It's a gorgeous score, mostly tonal, though spiked

with pungent dissonances. The composer seems to have abandoned his hard edge, and Neruda

Songs was so much the better for it.76

ISSUES OF TEXT

Associated Music Publishers, Inc. released the cycle in piano-vocal reduction in February

2011, two months before the composer's death, further bolstering the cycle's accessibility for

recital programming. Included were English translations by author Stephen Tapscott, who noted,

Literary translation is often a well-intentioned process of unfaithfulness in the service of

a greater fidelity. To make a readable poem in the target language, one needs to recreate

effects that parallel those of the original poem. The process commits strategic distortion,

for a trans-substantive effect. In some ways, the work a good translation does, finding

72

Lieberson, int. with Oteri, n.pag.

Kelly O'Connor, interview with user: gatheringnote. http://vimeo.com/17626836. Web.

74

Ibid.

75

Sheppard, n. pag.

76

Robert Hilferty, "Concerts Everywhere: New York City - Boston Symphony: Lieberson,

Strauss, Mahler," American Record Guide 69/2 (2006): 29.

73

26

ways to reconstitute the elusive "poetry," resembles the mandate of good musical

settings.77

Meant to be poetic translations rather than literal ones, Tapscott’s work on the Sonetos has been

generally well received. In fact, composers such as David Braid, Judith Cloud, Richard Peter

Maddox, Morten Lauridsen, and others have set several of his English poetic translations.78

Because he did not speak Spanish, it was Tapscott's translations that made Neruda’s poetry

available to Lieberson. The composer chose to set the original language, maintaining the

integrity of color and character of the sonnets. Lieberson found himself at ease with the love

sonnets, saying, “Perhaps I have some feeling for language. I don’t know. But Neruda’s Spanish

is very beautiful and so evocative and so melodic in its own way, so musical. I actually find

English the most difficult language to set.”79

Neruda's Cien Sonetos have a "plot" in their sequence that metaphorically suggests a

patterned relationship and a single day (in stages moving from day to night).80 It is easy to see

how organically the poems could be interpreted to represent the arc of a relationship or even the

transition from life to death. Lieberson's selection of sonnets and sensitive musical settings,

coupled with an intimate knowledge of his wife's instrument, created a cycle that offers a

concentrated microcosm of the Sonetos. Lieberson's settings enfold the narrative, "translating" it

to a dimension of experiential time that stretches out the statement, prolonging and deepening

and transmuting the melodic line faithfully and slowly, even in the vowels of the Spanish words

themselves—as if longing for a little more time.81

Stephen Tapscott, "Fidelity.” Opera News. 73/2 (August 2008): 68.

Ibid.

79

Ruhe, n. pag.

80

Tapscott, 68.

81

Tapscott,68.

77

78

27

POINTS FOR CONSIDERATION

Many critics and audiences familiar with the composer’s earlier works have agreed that a

substantial shift had occurred following his union with Hunt, but labeling his new style has

proved challenging. William Braun stated, “Lieberson's music, in its harmonic vocabulary, its

textures and its orchestration, is Bergian.”82 American composer, theorist, and distinguished

professor Stephen Taylor claimed that Lieberson’s late style is very much copied on that of Berg,

noting, “Much of the cycle sounds like Berg. In fact, the opening motive in the first song is

reminiscent of Lulu.”83 Although other scholars and reviewers have liberally applied the term

“Romantic” to this later style, such a designation is perhaps misleading because Lieberson was

not solely harkening back to an earlier period, but rather blending his early training with the

nuance of vocal writing learned from his wife. Though it does not condense into a tidy

classification, perhaps it would be more accurate to characterize Lieberson's new work as freer,

less cerebral, and more open to intuition while retaining his impeccable craftsmanship,

exquisitely colorful orchestration, and discerning critical ear.84 Lieberson’s work from this late

period consists of the first music that came to his mind, instead of utilizing the more formulaic

methods at which he excelled in academia. He said, “What I was looking for was something

pointed and poignant and very human, because it could expand out, so that it becomes

everyone’s experience.”85 This open-minded attitude toward accessibility would go far toward

endearing his works to audiences and critics alike. In Neruda Songs, Lieberson shed the angular

reticence of a lifetime and mined the florid intensity of Handel, the violent grace of flamenco,

82

Braun, n.pag.

Stephen A. Taylor. Personal interview. 8 April 2014.

84

Eddins, n.pag.

85

Lieberson, interviewed by Ruhe, n. pag.

83

28

and the elemental eloquence he learned from Lorraine Hunt.86

Each of the five songs presents a distinct collection of melodic and harmonic material.

Employing motive material creates unity amongst both the sections of the respective movements,

but also the cycle as a whole. In his original program notes, Lieberson described each sonnet as

reflecting “a different face in love’s mirror.”87 Despite the verses of the Chilean poet, Latin

influences are primarily confined to the use of maracas in the fourth song and the occasional

guitar-like spacing of some chords.88 The beauty of the poetry and the original language,

however, are enhanced by Lieberson’s sensitive settings. Rapid metric changes create a fluidity

of verbiage, maintaining and matching the integrity of Neruda's carefully chosen syntax within

the vocal line. In Raising the Gaze (1998), for example, Lieberson sought to evoke the spirit of

dance through a complex web of shifting meters.89 In Neruda Songs, the dance-like feeling is

maintained through this technique, but also creates a feeling of precariousness, even instability,

that propels the narrative forward toward the end: the end of the relationship and the end of the

life, but, we are gently reassured, not the end of the love.

INTERPRETATION

While Neruda Songs is most certainly a musical depiction of the arched trajectory of a

romantic relationship, I have found in the study of the songs a related lens through which to view

the cycle. Like Robert and Clara Schumann, who were struck by the tragedy of the German

86

Justin Davidson. "A Place of Shaggy Wildness." The New York Times, 13 May 2011. Web.

n.pag.

87

Deanna Hudgins. “Neruda Songs”. Los Angeles Philharmonic Music and Musicians

Database, n.d., n.pag.

88

Braun, n.pag.

89

Barrymore Laurence Scherer. A History of American Classical Music. Naperville, Illinois,

(2007): 215.

29

composer's deteriorating mental health, so were Lieberson and Hunt affected by the diagnosis of

her breast cancer.90 As the cycle was composed around or following the diagnosis of the

terminal illness, I assert that the songs can also be loosely viewed as representations of the five

stages of grief as introduced by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: grief, anger, bargaining, depression, and

acceptance. Originally conceived as a study to help caretakers and medical professionals better

serve dying patients,91 the stage model has been criticized because it projects an imagined series

of emotions that laypeople use a measurement of how a bereaved or terminally ill patient is

coping. Some of the harshest criticism of the model came from Kübler-Ross herself, when she

noted that the stages should be applied flexibly because some individuals may not feel every

emotion, or if they do, they may feel them in a different order than in the model. The five stages

have become a mainstay in social work, counseling, hospitals, medical schools, nursing

programs, seminaries, and popular media, as well as self-help literature for the bereaved

appearing in magazines, books and influential websites.92

Given their prevalence within our culture, it is possible that the stages played some part,

even subconsciously, in the compositional process of Neruda Songs. Given that music is often

used to express emotions, it is natural to wonder how many compositions have been written

within the various stages. Regarding Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, author Beverly

Lewis Parker asserts that the five stages of grief certainly seem applicable, though she states that

90

Katherine Kelton. Rilke Songs, The Six Realms (Violoncello and Orchestra), Horn Concerto

Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, mezzo-soprano; Peter Serkin, piano; Michaela Fukacova, violoncello;

William Purvis, horn. The Odense Symphony Orchestra, Justin Brown and Donald Palma,

conductors. Liner notes by Peter Lieberson and Robert Kirzinger; texts enclosed; English

translations by Stephen Mitchell. 2006. Bridge 9178. by Peter Lieberson. American Music 28:2

(Summer 2010), 257.

91

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying. New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1969.

92

Camille Wortman. "Coping with the Death of a Loved One: The Seductiveness of Stages",

This Emotional Life on PBS. Accessed 25 January 2014. Web. n.p.

30

it is not possible to know a composer's conscious intent during a work’s composition, nor can the

relationship between terminal illness and a work of art as merely a matter of cause and effect.93

This sentiment certainly applies to an examination of Neruda Songs. Just as Kübler-Ross stated

that the stages are not concrete, neither is their manifestation within Neruda Songs. When

considering the parallels between Kübler-Ross's theory and Lieberson's cycle, it is necessary to

keep in mind that speculation and subjective inquiry are necessary to humanistic studies.94 This

hypothesis is simply a micro-interpretation of a singular (yet profound) event in life, rather than

the macro-interpretation of the many levels of emotion that can accompany an entire

relationship.

In addition to the solo mezzo-soprano, Neruda Songs is scored for piccolo, two flutes,

oboe, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets,

vibraphone, glockenspiel, crotales, high suspended cymbal, maracas, low tom-tom or surdo (with

bass drum or other large beater), harp, piano and strings. The approximate performance time is

thirty minutes.

THE SONGS

The first song, “Si no fuera porque tus ojos tienen color de luna...” (If your eyes were not

the color of the moon), conjures up the infatuation at first glimpse of the beloved. This is not

unlike the sentiment exhibited in “Seit ich ihn gesehen” (Now I have seen him) in Schumann’s

Frauenliebe und –Leben. Whereas Schumann’s setting of Adelbert’s poetry praises all the things

the beloved is, Neruda’s text presents a converse list song, the text openly adoring the beloved:

"If you were not....., I could not love you." Another striking parallel is that both songs begin

93

Beverly Lewis Parker. "Parallels between Bartók's "Concerto for Orchestra" and KüblerRoss's Theory about the Dying", The Musical Quarterly 73:4 (1989): 533.

94

Ibid.

31

with a feeling other than overwhelming excitement—for Schumann, a breathless first glance; for

Lieberson, a languorous intoxication. Neruda's text is a converse list song ("If you were not..."

instead of "You are..."), presented in an “if-then” format. The A section provides a series of

antecedents, and it is not until the end of the B section that the first textual consequent is given.

The first three measures are sparsely orchestrated, yet perfectly embody the composer's

marking sultry, languid. Rapid changes of meter lend an air of unpredictability without

segmenting the work. The ascending bass motif ('languid') introduces the movement, is

presented several times throughout in both full and fragmented forms, and supports the singer's

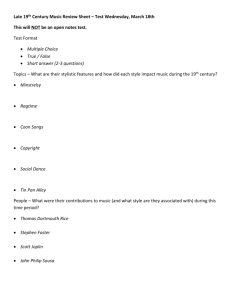

"Si no fuera" motive (Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Motives in “Si no fuera porque tus ojos…”

a) 'Languid' (mm. 1-2, accompaniment)

b) "Si no fuera..." (mm. 4-5, voice)

The inversion of the "si no fuera" theme at m. 19 indicates impending change. A spritely

32

new mood infuses the music at m. 22, the dancing marking of which is assisted by a sudden shift

into a lively 5/4. Drowsy luxuriousness gives way to vivacious abandon in the B section. The

light, dance-like qualities of this section evoke the “butterflies in the stomach” feeling of a

newfound interest.95 In this section, the music “dances” as marked, but also uses text painting to

depict the winding of the “enredaderas” (vines) with grupettos in both the accompaniment and

the voice. Both the text and music continue to intensify through the continuation of denied

resolutions through m. 28, until finally the accompaniment trills and cresecendos through a series

of cluster chords in ascending octaves (m. 30) towards the emphatic "Oh, bien amada!" This

emotional climax is also the first textual consequent—the 'then' to Neruda's list of “ifs.”

Melodically, the second repetition of "Yo no te amaría" is an altered treatment of the “languid”

theme, a scalar presentation with whole-tone flavor accompanied by a similar alteration in the

bass. Repetition of the text solidifies the depth of the lover's devotion as the now delicate

ascending motif carries the momentum upwards after the voice descends a perfect fifth at the end

of the phrase.

The second song, "Amor, amor, las nubes a la torre del cielo..." (Love, love, the clouds

went up the tower of the sky), captures the excitement of a freshly budding romance. Here is the

parallel to Schumann's second and third songs, “Er, der Herrlichste von allen” (He, the greatest

of all!) and "Ich kannst nicht fassen, nicht glauben" (I cannot grasp it, nor believe). Within in the

grief model, this movement could be interpreted as “denial”—a driving, almost frantic attempt to

maintain normalcy. While the first movement is sultry and languid, this movement leans toward

the exotic Espagne à la certain French composers such as Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy,

and features a sparkling orchestral introduction, a more melismatic vocal line, and snappy

95

Peter Lieberson, quoted in Hudgins, n.pag.

33

rhythms.96 This movement is joyful yet mysterious in its evocation of nature's elements: fire,

water, wind, and luminous space.97 Figure 2 shows the two main themes that are employed in

the A section (mm. 1-39).

Fig. 2: Motives in “Amor, amor, las nubes…”

1) Brilliant running (mm.1-4, accompaniment)

2) Joyful leaping (mm. 12-16, voice)

The use of shorter phrase lengths and text repetition creates the feeling of breathlessness.

With the exception of the 4/8 bar at m.4, the A section contains a long passage of music in the

same meter (mm. 1-44). The A' section provides additional metric stability in mm. 51-93, again

varying only once in m. 54. More than the others, this song pulses with an unrelenting

96

W. A. Sheppard. "Recording Reviews: Peter Lieberson - "Rilke Songs"; "The Six Realms";

Horn Concerto; "Neruda Songs". Journal for the Society of American Music 4, no. 1 (2010): 114.

97

Peter Lieberson. Composer's note. Neruda Songs. With poetry by Pablo Neruda, translations

by Stephen Tapscott. Milwaukee, WI: Associated Music Publishers, Inc., 2011. Print.

34

persistence that builds tension through the first section, refusing to linger in any one tonal area

too long. The leaping melodic contour and repetition of the word “amor” in mm.12-16 feels

frenetic, almost mechanical. The melisma in mm. 23-26, which the accompaniment imitates,

feels constricted with its limited range and lack of forward motion. A second melisma in m.31

breaks free, fittingly on the word “triumfantes”, covering a wider range and thus propelling the

energy towards the climax of "y todo ardió en azul" in mm. 36-39. A short transitional passage

(mm. 40-44) calms the exhilaration of the first section with a ritardando and decrescendo, thus

ushering in the B section.

This section, marked “suspended”, undulates gently under Neruda's words with a floating

D-flat, E-flat, G-flat, and A-flat cluster chord presented in three octaves, and a pedal E-flat

firmly in the bass. The calm of this moment is fleeting, however, as A' suddenly reengages in

mm.51-93, utilizing motivic material from the A section. Measure 94 begins a new section, C,

marked “meno mosso” with a shift to 6/8 and a return to E-flat as the implied tonal area. Within

the moods of the A’ and C sections respectively, Lieberson achieves continuity through the use

of altered vocal material from the opening section (Figure 3). In the A’ section, the text invites

one to "come to see the starry cherry water"- the color red is presented in florid motion, as it is

with the word "love" in the first A section, which also associated with red. The arch of the

melodic contour crests very rapidly, with the highest note (F) occurring as a 32nd note on the

final beat of m. 66. The final interval of the excerpt is a perfect fourth. In the C section, the text

also invites one to "come to touch the fire of instant blue" - blue is represented by a more tranquil

tempo and relaxed delivery of the text. In addition, the arch is not a singular motion, but an

extended presentation in which rests are included. The climax occurs on the downbeat of m. 99,

finally allowing the note to blossom before continuing the phrase, which ends with a metrically-

35

extended version of the same interval in the first excerpt.

Fig. 3: Alteration of vocal thematic material in “Amor, amor, las nubes…”

a) “Ven a ver” (mm. 63-69, voice)

b) "Ven a tocar" ( mm. 96-98, voice)

An expansive, recitative-like passage follows the C section, in which tremolos and rolled

chords dominate the accompaniment. The vocal line is fragmentary, as if making a series of

divine discoveries in one’s surroundings and trying to take in all the wonder. The delicate

rippling of the accompaniment creates a current of sound that pulses towards the final section,

which is preceded by a final instance of the “brilliant” theme presented as the singer's first

limited melisma. This time, however, the melisma feels more connected to both its present

location and the coming material. Additionally, the melisma seems to break away from the

limited range by falling a seventh from C-flat to D-flat, an interval greater than any of its

predecessors. The melisma becomes a transitional vehicle for the final section.

Measure 129 begins the final section, B'. Though it appears markedly different from the

original B, the two sections share a similar mood (marked “tranquillo”, the first “suspended”).

Again, the evocation of mood is charged by the mention of “azul” in m.130 and a sense of calm

prevails. Additionally, though now in bass clef, the pitch content is the same as the first

36

presentation of the material. There is now an interesting division of the beat, in the 32nd notes

with rests interspersed. This division of the beat could be interpreted as mimicking the lapping

of waves, or more intimately, a heartbeat. This rhythmic motion ends the song, after all of the

rhythmic force and vitality of the opening, is both poignant and reassuring. From the perspective

of the stages, the heartbeat serves as a calming transition from the intensity of denial to the

aching of depression in the next song. In this section, Lieberson uses material from the first

movement (Figure 4) to connect these two songs which share poetry from Neruda's Morning

section. Additionally, m. 140 introduces a grupetto figure that figures prominently into the

following movement.

Fig. 4: Recurrence of thematic material as unifying factor between Songs 1 and 2

4a) Text and contour of 'del aire'

i. "Si no fuera..."( mm. 13-14, voice)

ii. "Amor, amor, las nubes...", (mm. 133-34, voice)

37

4b) Ending interval of vocal lines

i. "Si no fuera..." ( mm. 63-64, voice)

ii. "Amor, amor, las nubes..." (mm.137, voice)

The center song of Lieberson’s arch, “No estes lejos de mí un solo día” ("Don’t go far

off, not even for a day”), suddenly pivots in mood. From the jumble of emotions in Neruda's

Morning section, there is a jarring turn into Afternoon. The love has deepened, and the

dependency on the beloved is displayed in the largo movement. The singer’s lament of fear is

represented by the textual repetition and tightly knit melodic line, as if an attempt to enfold the

lover musically, and keep him or her in place.98 This then could be imitation of life—perhaps a

musical manifestation of the despair or depression that can accompany a life-altering event, such

a cancer diagnosis. The narrator pleads repeatedly (or in Kübler-Ross' model, bargains)

desperately with the encroaching feelings of desolation that accompany the thought of parting

with a beloved.

98

Sheppard, 114.

38

The ear recognizes D-sharp, the first notated pitch, as the tonal center for the movement.

This low, ominous note sets a somber tone that is enhanced by the hollow open sonority above

which the singers enters in m.3. For much of the song, the E-flat sounds as a pedal tone,

anchoring the perception of key much as the narrator seeks to anchor the beloved. Two distinct

motives appear emerge: 1) the pleading of "no estés lejos de mi" stepwise ascending, then leaps

falling and 2) the sighing "un solo día" (Figure 5). Altered variations of these two main themes

appear throughout, providing further unification throughout the piece (Figure 6).

Fig. 5: Motives in “No estés lejos de mi…”

a) Pleading (m. 3, voice)

b) Sighing theme (m. 5, voice)

Fig. 6: Alterations of themes

a) Pleading (m. 21, voice)

39

b) Pleading (mm. 57-61, voice)

c) Sighing (mm. 36-39, voice)

The fourth song,“Ya eres mía. Reposa con tu sueño en mi sueño” (And you are mine.

Rest with your dream in my dream), begins with a declamatory, almost frenzied repetition of the

first line. The repetition of a triplet figure with its accented first beat seems to summon the

40

vocalist. Although A-like material returns at the end of the piece, this figure is featured only

once, and in altered, incomplete form at m. 130 (an interpretation of abridged themes in the final

section, mm. 129-134 is discussed later). Interestingly, the first two instances of "Ya eres mía"

begin with the melodic emphasis on the word "mine," but the next three place greater emphasis

on "and you" through a descending pattern, perhaps an homage to the equal partnership between

the two lovers following the reassurance that the beloved will “not go far off,” from the previous

movement. Though the text is comforting, the accentuated opening section creates an aura of

insistence or even perhaps anger that the beloved has only just now been found and time is

running out. The foreboding mood is supplemented by the use of jarring melodic interval

relationships, especially on words with generally positive associations, such as “dreams,” “love,”

and “eyes”, respectively (Figure 8).

Fig. 8: Instances of musical 'foreboding' in “Ya eres mía. Reposa con tu sueño…”

a) Tritone on "sueño” (m. 11, beats 3 & 4, voice)

b) Tritone, dissonance in chord "amor" (m. 23 b. 3 A flat to D natural and the

presence of a minor second in m. 24, b. 1, accompaniment)

41

c) Tritone on "ojos" (m. 98, beat 1, voice)

With these examples in mind, a strong case can be made for the influence of KüblerRoss's stages. The omission of any poetry from the Evening section might represent the sudden,

jarring diagnosis of terminal illness—lovers suddenly thrust into night without the gentle fade of

light during the evening hours. The listener is thrust into the poetry of Neruda's Night, and

Lieberson employs an interesting concept to suddenly thrust the listener into a new soundscape;

the inclusion of a Latin American bossa nova rhythm in the middle of the song seems at once

puzzling, and does not appear clearly motivated by anything in the poetry.99 It does, however,

introduce a new and drastically different ambiance within the cycle. The snappy Latin rhythms

might also represent a final surge of energy, allowing a moment of brief respite from the

impending finality. Syncopation is prevalent throughout, with two main themes providing

continuity (Figure 9). The first motive, found only in the accompaniment, employs a contrary

sweeping motion in opposite direction across the bar line to usher in a decisive chord on the

99

Sheppard,115.

42

downbeat. The second motive stresses the bossa nova groove, as it occurs mostly on usually

unstressed beats of a measure, is pitched higher, and marked staccato against a more static

texture underneath. Frequent metric changes create both feelings of precariousness and perpetual

motion.

Fig. 9: Motives in “Ya eres mía. Reposa con tu sueño…”

a) Contrary 'sweeping' motion (m. 4, accompaniment)

b) 'Sweeping' motive (m. 73-74, accompaniment – into instrumental interlude)

c) 'Groove' rhythm (m. 13, accompaniment)

43

d) 'Groove' rhythm (m. 26-30, accompaniment)

Once again, this movement bears a similarity to Schumann’s Lieder in that the

accompaniment and voice share equal importance in the storytelling. This technique is clearly

displayed beginning with the pickup to m. 68. The voice gradually intensifies and broadens,

essentially passing the storyline to the accompaniment in mm. 74-90. The contrary sweeping

motive ushers in the interlude, dispelling the illusion of divisiveness as a lush chord (C, D, E-flat,

B-flat, F) blossoms on the downbeat of m. 74. The sweeping motive creates a series of rushes—a

similar but smaller one occurs at m. 108, followed by a larger one at m. 116—perhaps one last

burst of energy, of life's blood. A third instance occurs in mm. 128-129, but fails to achieve the

intensity of any of its predecessors, as if all of the energy has been spent and all that remains is a

bittersweet memory of such vitality. Neither the voice nor the accompaniment will attain that

level of intensity for the remainder of the cycle. Following its turn as narrator, the

accompaniment reengages the lively syncopated rhythm at m. 91, as if inviting the voice to join

once again.

44