the Case for Support

advertisement

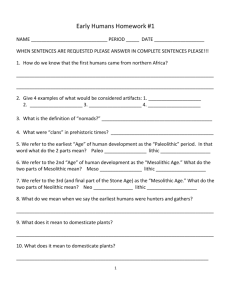

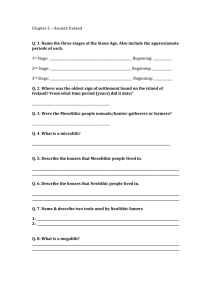

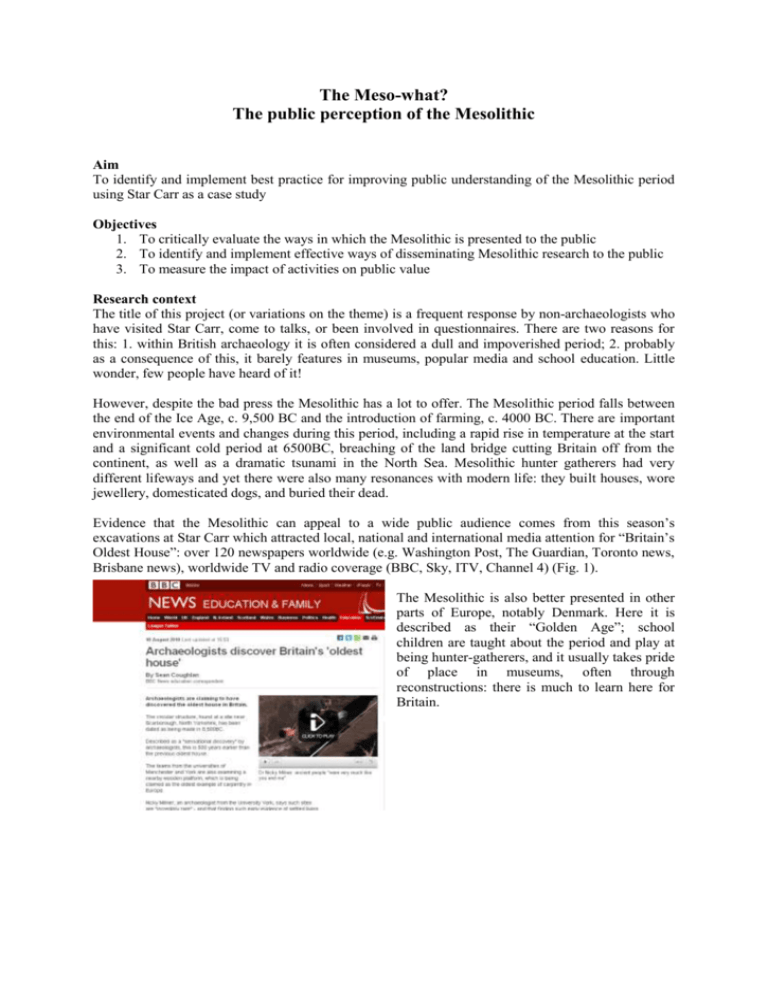

The Meso-what? The public perception of the Mesolithic Aim To identify and implement best practice for improving public understanding of the Mesolithic period using Star Carr as a case study Objectives 1. To critically evaluate the ways in which the Mesolithic is presented to the public 2. To identify and implement effective ways of disseminating Mesolithic research to the public 3. To measure the impact of activities on public value Research context The title of this project (or variations on the theme) is a frequent response by non-archaeologists who have visited Star Carr, come to talks, or been involved in questionnaires. There are two reasons for this: 1. within British archaeology it is often considered a dull and impoverished period; 2. probably as a consequence of this, it barely features in museums, popular media and school education. Little wonder, few people have heard of it! However, despite the bad press the Mesolithic has a lot to offer. The Mesolithic period falls between the end of the Ice Age, c. 9,500 BC and the introduction of farming, c. 4000 BC. There are important environmental events and changes during this period, including a rapid rise in temperature at the start and a significant cold period at 6500BC, breaching of the land bridge cutting Britain off from the continent, as well as a dramatic tsunami in the North Sea. Mesolithic hunter gatherers had very different lifeways and yet there were also many resonances with modern life: they built houses, wore jewellery, domesticated dogs, and buried their dead. Evidence that the Mesolithic can appeal to a wide public audience comes from this season’s excavations at Star Carr which attracted local, national and international media attention for “Britain’s Oldest House”: over 120 newspapers worldwide (e.g. Washington Post, The Guardian, Toronto news, Brisbane news), worldwide TV and radio coverage (BBC, Sky, ITV, Channel 4) (Fig. 1). The Mesolithic is also better presented in other parts of Europe, notably Denmark. Here it is described as their “Golden Age”; school children are taught about the period and play at being hunter-gatherers, and it usually takes pride of place in museums, often through reconstructions: there is much to learn here for Britain. Fig 1:Media coverage of Star Carr, summer 2010 Star Carr is Britain’s most important Mesolithic site and provides great potential for engaging the public. It was situated on the edge of a lake which has subsequently turned to peat, resulting in incredible preservation of organics. The initial excavations by Clark (1954) produced 191 harpoons, 21 antler headdresses, antler mattocks, bone scrapers and awls, a wooden paddle, amber and shale beads, and a large assemblage of faunal remains. These are all incredibly rare finds, in fact the majority of types have not been found elsewhere in Britain. In the 1980s further excavations revealed a timber platform/trackway, constructed of split planks: the earliest evidence of systematic carpentry in Europe (Mellars and Dark 1998). Excavations since 2004 have revealed the earliest “house” in Britain, further evidence for the platform (Fig. 2) and the size of the site and longevity of occupation suggests that people were settling into this landscape, as opposed to being constantly mobile as previously thought (Conneller et al 2009a, 2009b). In addition, landscape research around Star Carr over the last 30 years has allowed us to model the extent of the lake and led to the discovery of over 15 other Early Mesolithic sites, although none are comparable to Star Carr. The importance of Star Carr Fig 2: Uncovering the platform has recently been recognised by English Heritage, who are about to schedule the site as a National Monument, however, what is surprising is that even though the site is world renowned in archaeology, it has barely been heard of by the locals. Milner has been aware of this lack of local public knowledge having grown up in the region and having worked in the Vale of Pickering on excavations for the past 20 years. She has taken a personal interest in developing public outreach as part of the Star Carr project and over the last few years has given numerous talks to local societies, site visits and created a webpage. However, surveys conducted in Scarborough in October 2009 and 2010 demonstrate that less than 7% of local people have heard of Star Carr and the qualitative data shows that their understanding of the nature of the site is extremely poor, e.g. “Heard about it but not really sure what it is about”. The Partnership This partnership came about following discussions between Milner and Walker regarding possible public outreach activities for Star Carr. Whereas the Vikings and Romans are easier to “sell” to the public because they are taught in schools and frequently appear in the media, the Mesolithic presents a much greater challenge which both partners are extremely keen to take up. The partners wish to collaborate in order to find sustainable ways of bringing the Mesolithic period to public attention through Star Carr. The proposed collaboration between Milner and Walker is new although Milner has collaborated with YAT previously in the study of degradation at Star Carr. There are other collaborations between the department of Archaeology and YAT; however, this partnership will be an original venture which explicitly links academic research with public outreach. Although other collaborations could have been sought, YAT has an exceptionally strong record in this field with Jorvik, DIG and Barley Hall having attracted over 16 million visitors and this is therefore the rationale for continuing the relationship. Research Questions and methodology 1. In what ways is the Mesolithic presented to the public in Britain? The student will assess the ways in which the Mesolithic is currently being presented and how sustainable it is, through visits to museums, identifying popular literature (like the new cartoon book “Mezolith” and other recent novels), and media such as TV and radio. 2. In what ways is the Mesolithic presented to the public in other European countries, particularly Denmark? A similar exercise will be undertaken in Europe making use of Milner’s contacts in Denmark, Norway, Spain, and Germany where a variety of different media and museum displays are used, in some cases with a great deal of success (visitor numbers, books sales, school curricula). 3. Which methods of presenting the past are best applicable to the Mesolithic? The student will spend time in YAT’s visitor attractions in order to consider the many different ways the past can be presented to the public and how these might translate to the Mesolithic period. Different types of activity will be planned and implemented for Star Carr. 4. Which aspects of Mesolithic lifeways are more likely to engage a public audience? This will be assessed through studying other periods (particularly the Vikings and Romans through the YAT attractions), and the Mesolithic in other countries: e.g. are issues such as climate change, which is at the forefront of current media, of interest when considered in the past. 5. How effective are different types of outreach activities? Detailed monitoring of activities will take place using data such as visitor numbers and questionnaires in order to assess the impact of the different types of activity undertaken. Surveys will continue to be undertaken in Scarborough in order to identify whether the site acquires a higher profile over the period of the PhD. Timescales The PhD will be constructed of two phases: 1. assessment of current practices for disseminating Mesolithic research in Britain and selected parts of Europe, as well as evaluating the innovative methods used for other periods through working with YAT. Towards the end of the first year proposals should be in place for the excavation in the summer (e.g. on-site visitor attractions) and for further dissemination activities during the second year (e.g. engagement with schools). 2. the development and evaluation of these activities. The writing up should be continuous as data is collated and the thesis will consist of chapters covering evaluation of current practices in Britain and in Europe, the diverse and innovative ways of disseminating information about the past, the implementation of outreach for Star Carr, and the impact of the approach with evaluations for further long term initiatives such as visitor centres. Plans for Dissemination Academic audience: the findings will be disseminated for an academic audience interested in promoting their research beyond the academic realm for public value. They will be published in academic journals such as “Antiquity” and “Public Archaeology”, at Mesolithic conferences and at interdisciplinary seminars through the Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past. Public value: research on Star Carr will be disseminated in a variety of different ways depending on the assessments carried out in phase 1. It will be important to engage school children and to find ways in which the Mesolithic can be used in areas of the curriculum. It is anticipated that educational materials will be developed which can be downloaded from the website. Another aspect of the project is to consider how/whether modern technology and social networking can be used in particular to engage younger audiences, e.g. podcasts/vodcasts, apps, twitter and facebook. However, more traditional methods will also be evaluated such as talks, workshops, leaflets, and walks. Public bodies: the results of this work will be disseminated to public bodies such as English Heritage, North Yorkshire County Council and Natural England through seminars and publications. Expected Outcomes Academic outcomes: much of the research will consider and experiment with different ways of communicating research, including innovative methods and modern technology; the project will therefore act as an important case study which can be used by other academics to enhance public value in research. Public value: the local area should benefit culturally through an increase in resources and educational materials provided on-site, in local displays (in York through YAT, and possibly through the local museum) and on-line resources. Potentially there will also be economic benefit through visitors to the area, particularly during the summer when they may also use local pubs, b and bs/hotels etc. Public bodies: English Heritage is in the process of writing a Vale of Pickering Historic Environment Management Framework in which public value plays a key role: the results of this PhD will be key to this ongoing initiative. Much of the focus of the PhD will be to test different approaches but it is anticipated that these will lead to further developments beyond the PhD which may include initiatives such as a visitor centre and/or a permanent museum display. Benefit of the Collaboration The PhD student: the student will benefit from working in collaboration between a University department and YAT (the local market leader in educational activities and visitor attractions), as well as working with other local bodies and agencies (local societies, museums, English Heritage). The student will also be exposed to practices in other countries and will build up those networks further through visits and conference presentations. The collaboration will provide extremely valuable benefits to both parties: the department of Archaeology will gain expertise in the development of educational archaeological public attractions (which can be disseminated to a wider, interdisciplinary academic audience) and YAT will gain the opportunity to diversify into prehistory and engage a new audience in the Vale of Pickering. They will also benefit from the research carried out in Europe. It is intended that this project will stimulate others like it as well as creating sustainable resources which will be used long after the PhD project has concluded. Bibliography Clark, J (1954) Excavations at Star Carr, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Conneller, C., Milner, N., Schadla-Hall, T. and Taylor, B. (2009a) The temporality of the Mesolithic landscape: new work at Star Carr. In Crombé, P., et al. (eds) Chronology and Evolution within the Mesolithic of North-West Europe. 77-94. Cambridge Scholars Conneller, C., Milner, N., Schadla-Hall, R.T. and Taylor, B. (2009b) Star Carr in the new millenium, In Finlay, N., et al. (eds) From Bann flakes to Bushmills, Prehistoric Society No 1, 7888. Oxford: Oxbow Mellars, P and Dark, P (eds) Star Carr in context, Cambridge: MacDonald Institute