Public perception and understanding of the

advertisement

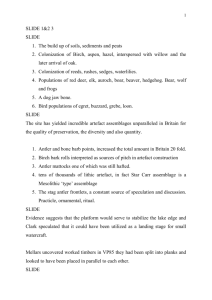

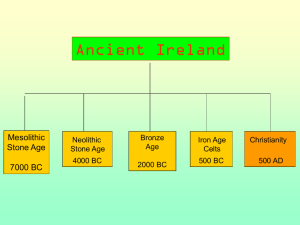

The Meso-what? Public perception and understanding of the Mesolithic Doctoral Research Project | Patrick Hadley |2011-2014 An AHRC funded Collaborative Doctoral Award supervised by Nicky Milner (University of York) and John Walker (York Archaeological Trust) Research Design (version 1.0 |10 November 2011) Versions of this design produced during the application process are available online: CDA Proposal: https://wiki.york.ac.uk/display/~ph618/CDA+Proposal Case for support: https://wiki.york.ac.uk/display/~ph618/Proposal+support There is also a proposal submitted for a direct AHRC scholarship by Patrick Hadley: Scholarhip proposal: https://wiki.york.ac.uk/display/~ph618/Research+proposal Aim: To identify and implement best practice for improving public understanding of the Mesolithic period using Star Carr as a case study. Objectives: 1. To critically evaluate the ways in which the Mesolithic is presented to the public in Britain 2. To investigate the ways in which the Mesolithic is presented to the public in other parts of Europe 3. To identify effective ways of disseminating Mesolithic research to the public, particularly through engagement with YAT attractions 4. To implement ideas for disseminating Mesolithic research, using Star Carr as a case study 5. To measure the impact of various presentation types Research Context: Public awareness of the Mesolithic is generally very poor when compared with other periods in Britain’s past (hence the title; many people’s initial reaction to the word ‘Mesolithic’). This contrasts with the consistently enthusiastic reception to the scattered media presentations of the period. For example; the international press-coverage of the Star Carr ‘house’ (Aug. 2010), the BBC’s recent flagship series A History of Ancient Britain (Feb. 2011), Ray Mears’ book and series Wild Food (2007), and the National Geographic Channel’s Stone Age Atlantis (2010). This patchy enthusiasm does not translate into general public recognition or understanding of the Mesolithic. This is partly because the period is often still regarded as dull or impoverished by British archaeologists and it barely features in museums, and gets no coverage in schools. This contrasts with the presentation of the period in other parts of Europe, notably Denmark. Here it is described as their “Golden Age”; school children are taught about the period and play at being hunter-gatherers, and it usually takes pride of place in museums, often through reconstructions: there is much to learn here for Britain. Star Carr - Britain’s most important Mesolithic site - provides great potential for engaging the public. It was situated on the edge of a lake which has subsequently turned to peat, resulting in incredible preservation of organics. The initial excavations by Clark (1954) produced 191 harpoons, 21 antler headdresses, antler mattocks, bone scrapers and awls, amber and shale beads, and a large assemblage of faunal remains. These are all incredibly rare finds, in fact the majority of types have not been found elsewhere in Britain. In the 1980s further excavations revealed a timber platform/trackway, constructed of split planks: the earliest evidence of systematic carpentry in Europe (P. Mellars & P. Darkeds. , 1998). Excavations since 2004 have revealed the earliest “house” in Britain, further evidence for the platform and the size of the site and longevity of occupation suggests that people were settling into this landscape, as opposed to being constantly mobile as previously thought (Conneller et al., 2009a, 2009b). In addition, landscape research around Star Carr over the last 30 years has allowed us to model the extent of the lake and led to the discovery of over 15 other Early Mesolithic sites, although none are comparable to Star Carr. The site and its landscape is about to go into a further 5-year phase of investigations: this fieldwork will act as a focal point for this project and enable the ‘live’ presentation of the latest discoveries. The importance of Star Carr has recently been recognised by English Heritage, who are about to schedule the site as a National Monument, and it is regularly taught as a key part of archaeology undergraduate courses world-wide. Despite this, the site has virtually no public profile nationally, in Yorkshire or even among locals. Surveys conducted in Scarborough in October 2009 and 2010 demonstrate that less than 7% of local people have heard of Star Carr. Research questions and methodology 1. In what ways is the Mesolithic presented to the public in Britain? There are several key ‘interfaces’ or channels through which archaeological information gets from specialists to the public. These include museums, traditional media (radio, television, newspapers), schools, popular books (non-fiction and fiction), performances, artworks, direct outreach (public lectures, site tours, experimental archaeology), archaeological/historical societies and specifically web-based dissemination. It will be crucial to investigate the relative strengths and weaknesses of these interfaces in terms of audience size, penetration, engagement and overall effectiveness as tools for presenting the Mesolithic. 2. In what ways is the Mesolithic presented to the public in other European countries, particularly Denmark? Comparisons of the use of these interfaces in other regions will help build understanding of appropriate ways to present the Mesolithic. Particularly good examples of presentation sites (museums, archaeo-parks, excavation sites) will be selected for visits and broader datasets (visitor numbers, books sales, school curricula) will be analysed. The reasons for the uneven representation of Mesolithic archaeology across Europe will be placed in a historical context. 3. Which interfaces are most effective for presenting the Mesolithic? It is important to gain a detailed understanding of how various aspects of the past can be presented by spending time at YAT’s visitor attractions. By comparing these to other interfaces in Britain and Europe one can build an understanding of how these might translate to the Mesolithic period. Different types of activity will be planned and implemented for Star Carr including one-off events (tours, lectures, performances), engaging traditional media, using webbased dissemination. 4. Which aspects of the Mesolithic are best suited to various public audiences? Through the study of other periods (particularly the Vikings and Romans through the YAT attractions), and the Mesolithic in other countries it should be possible to assess if any issues have particularly high-impact with the broadest audiences: e.g. are issues such as climate change, which is at the forefront of current media, of interest when considered in the past. Further, are particular aspects more suitable for different age groups, non-traditional audiences (those from lower socio-economic backgrounds or recent immigrants). Lastly, there is an issue of whether particular ‘interpretive communities’ (eg, Hooper-Greenhill, 2007) have particular ways of engaging with the Mesolithic which can be utilised (or must be mitigated for): for example flint-collectors, New Age spiritualists or extreme nationalists. 5. How effective are different interfaces for various audiences? By collating data from indirect presentations (book sales, museum visitors, television audiences) and detailed monitoring of direct-engagement activities (visitor numbers, questionnaires, interviews) it should be possible to assess the impact of the different interfaces as Mesolithic presentation tools. Surveys will continue to be undertaken in Scarborough in order to identify whether the site acquires a higher profile over the period of the PhD. Timescales and workflow The PhD will be constructed of several phases: 1. The assessment of current practices for disseminating Mesolithic research in Britain and selected parts of Europe, as well as evaluating the innovative methods used for other periods, particularly through work with YAT. 2. Towards the end of the first year proposals should be in place for the excavation in the summer (eg, on-site visitor attractions) and for further dissemination activities during the second year (eg, engagement with schools). 3. These phases will be built upon with development and evaluation of these activities. This reflexive methodology will enable relevant areas of investigation to be broadened or deepened. The writing up should be continuous as data is collated and the thesis will consist of chapters covering evaluation of current practices in Britain and in Europe, the diverse and innovative ways of disseminating information about the past, the implementation of outreach for Star Carr, and the impact of the approach with evaluations for further long term initiatives such as visitor centres. Relevant literature The project obviously straddles a number of relevant literatures: in addition to a broad understanding of Mesolithic studies, museum studies, media theory, heritage studies will all have to be investigated as necessary. Expected outcomes 1. Academic outcomes: much of the research will consider and experiment with different ways of communicating research, including innovative methods and modern technology; the project will therefore act as an important case study which can be used by other academics to enhance public value in research. 2. Public value: the local area should benefit culturally through an increase in resources and educational materials provided on-site, in local displays (in York through YAT, and possibly through the local museum) and on-line resources. Potentially there will also be economic benefit through visitors to the area, particularly during the summer when they may also use local pubs, B&B’s, hotels etc. 3. Public bodies: English Heritage is in the process of writing a Vale of Pickering Historic Environment Management Framework in which public value plays a key role: the results of this PhD will be key to this on-going initiative. Much of the focus of the PhD will be to test different approaches but it is anticipated that these will lead to further developments beyond the PhD which may include initiatives such as a visitor centre and/or a permanent museum display. Bibliography Clark, J.G.D. (1954). Excavations At Star Carr: An Early Mesolithic Site at Seamer Near Scarborough, Yorkshire. 1st Ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Conneller, C., Milner, N., Schadla-Hall, R.T. & Taylor, B. (2009a). Star Carr in the new millenium. In: N. Finlay, S. McCartan, N. Milner, & C. R. Wickham-Jones (eds.). From Bann Flakes to Bushmills : papers in honour of Professor Peter Woodman. [Online]. Oxford ;Oakville CT: Oxbow Books ;;David Brown Book Co. [distributor], pp. 78-88. Available from: http://cedadocs.badc.rl.ac.uk/315/. Conneller, C., Milner, N., Schadla-Hall, R.T. & Taylor, B. (2009b). The Temporality of the Mesolithic Landscape: New Work at Star Carr. In: P. Crombé, M. Van Strydonck, J. Sergant, M. Boudin, & M. Bats (eds.). Chronology and evolution within the Mesolithic of North-West Europe: proceedings of an international meeting, Brussels, May 30th-June 1st 2007. Newcastle upon Tyne UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 77-94. Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2007). Interpretive Communities, Strategies and Repertoires. In: S. Watson (ed.). Museums and their communities. London: Routledge, pp. 76-94. P. Mellars & P. Dark (eds.) (1998). Star Carr in context. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research Cambridge.