notes - York Wiki Service

advertisement

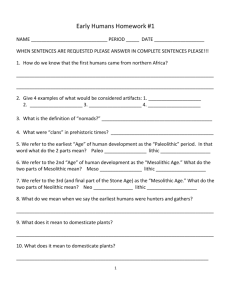

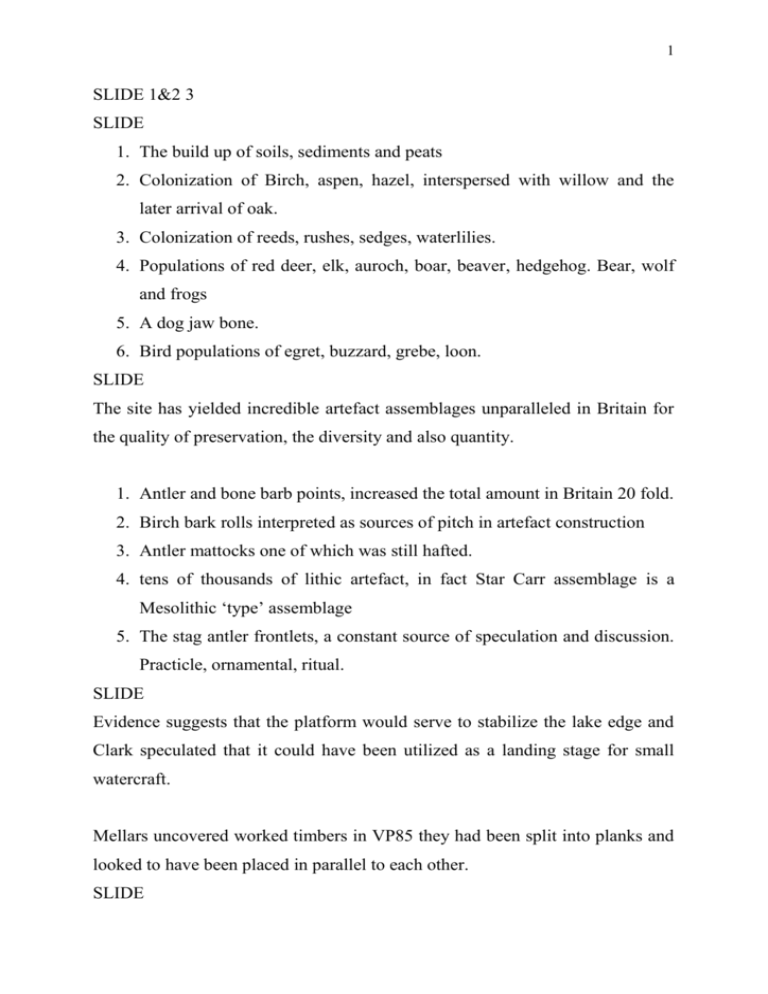

1 SLIDE 1&2 3 SLIDE 1. The build up of soils, sediments and peats 2. Colonization of Birch, aspen, hazel, interspersed with willow and the later arrival of oak. 3. Colonization of reeds, rushes, sedges, waterlilies. 4. Populations of red deer, elk, auroch, boar, beaver, hedgehog. Bear, wolf and frogs 5. A dog jaw bone. 6. Bird populations of egret, buzzard, grebe, loon. SLIDE The site has yielded incredible artefact assemblages unparalleled in Britain for the quality of preservation, the diversity and also quantity. 1. Antler and bone barb points, increased the total amount in Britain 20 fold. 2. Birch bark rolls interpreted as sources of pitch in artefact construction 3. Antler mattocks one of which was still hafted. 4. tens of thousands of lithic artefact, in fact Star Carr assemblage is a Mesolithic ‘type’ assemblage 5. The stag antler frontlets, a constant source of speculation and discussion. Practicle, ornamental, ritual. SLIDE Evidence suggests that the platform would serve to stabilize the lake edge and Clark speculated that it could have been utilized as a landing stage for small watercraft. Mellars uncovered worked timbers in VP85 they had been split into planks and looked to have been placed in parallel to each other. SLIDE 2 The research questions that have dominated study of Star Carr can be easily broken down into major categories. 1. Chronolgy. When was the site occupied? brushwood platform 9488± 350 bp by Libby Britain’s first radiocarbon date. The timber platform giving a date of 9640±70 bp 2. How long was the site occupied? Clark’s interpretation was for two occupation intervals separated by an expanse of several generations. He identified two design styles in the barbed points that were also separated in different contexts. In the 80s Mellars’ application of AMS dating identified three contexts with higher occurrences of charcoal. These were dated and have a sequence spanning three possible occupation events from 9640±70 bp to 9385±115bp. 3. At what season was the site occupied?. Based on the shedding of antlers, the presence of deer skulls with antlers attached and the mandibles of hunted animals interpretation has ranged from winter occupation and summer occupation. Stone artifacts and other resources further suggest the longe-range mobility of Mesolithic groups obtaining flint from the Wolds, amber from the coast and hunting animals in the Pennines. 4. What kind of settlement was Star Carr? Again this question has inspired many interpretations from being a temporary hunting camp, a permanent winter base camp and also either a place of productive activity or a place of discard a so-called toss zone. Clark speculated the site was occupied by around four family units and that he’d excavated the full extent of the site. Further test pitting by Mellars indicated that the site extended over a much larger area and current estimations suggest that as little as 5% of the site has been excavated. 5. Less so but more so recently questions surrounding the social and ideological lives of Star Carr’s inhabitants have arisen. Clark mentions 3 the activities of men, women and children and possible rituals involving red deer masks. Mellars interpreted the increased frequencies of charcoal in some of the contexts as evidence of reed burning and a form of fire stick economy. Conneller has discussed the site as a special locale, repeatedly returned to as a significant area. The unusual deposition of so many barbed points when the other sites have yielded only one seems to suggest that the site is an anomaly in the Mesolithic landscape. SLIDE Where do these research questions come from? Exploring this question it soon becomes apparent that the use of analogy has been integral to the study of Star Carr. As Spikins has pointed out these research questions can be easily traced back to Clark’s 1972 Star Carr a case study in Bioarchaeology. Clark’s states that at the same time as the discovery of Star Carr he was progressing theoretically from being solely concerned with typology and stratigraphy. Clark had been interested in these aspects to arrive at a relative date for the site. Clark used Godwin’s pollen zones these were based on analogies of ecological zones from different latitudes to determine the vegetation progression and colonization of the British Isles from the end of the Ice Age. Clark also used artefact typological analogies to suggest cultural affiliations with Scandinavian and Northern European Mesolithic sites. Clark had become increasingly interested in the environment not solely as a temporal indicator but as a cultural one. Clark identified Mesolithic populations as hunter-gatherers and based his interpretations on functional anthropological and cultural ecological theories of the time. Therefore the environment became an indicator of the cultural forms of human populations that existed within it. 4 Cultural change could be described through the interaction of environmental subsystems interacting and directly affecting cultural subsystems. Thus British Mesolithic studies paralleled hunter-gatherer studies with an agenda borrowed from anthropology and cultural ecology typified by the research questions at Star Carr. Is it possible to identify further the origins of these research questions and Clark’s and others identification of the Mesolithic as the realm of H&Gs? SLIDE This is not difficult as Clark is emphatic in Excavations at Star Carr that he was searching for a site to illustrate a step in evolutionary progression firstly in relation to Maglomosian sites throughout Europe. Secondly he intended to illustrate the differences in occupation densities of Mesolithic and early Neolithic sites. This is the underlying factor in how Clark even recorded the site of flint accumulations per square yard. SLIDE This evolutionary agenda can be easily identified in the very foundations of Prehistoric studies and ethnographic analogy has been fundamental to this course of study. In 1865 one of prehistory’s founding fathers John Lubbock published the book “Pre-Historic Times as illustrated by Ancient Remains, and the Manners and Customs of Modern Savages.” The concept of a primitive point from which populations would evolve in increasing complexity became part of the colonizing philosophy of the European and American Empires. Making modern populations primitive by comparing them with a less civilized European origin it was possible to ‘speed’ up their evolution by disenfranchising them from their lands, indoctrinating 5 them into the Empire or deselecting them through acts of genocide. Comparing the past to modern ‘primitives’ reinforced the philosophy of Western superiority and sophisticated complexity. Therefore, as the World was colonized, human history was equally colonized by conceptual means. SLIDE There are plenty of cultural analogies derived from research at Star Carr some are quite specific yet most are very vague. They are from all over the world and they come from studies that range in time. From recent photographic evidence, dinka, to 18th century texts, the poor of Denmark and this is just a quick selection from Clark and Mellars. SLIDE In 1954 as Clark published Excavations at Star Carr Christopher Hawkes famous paper appeared that condemned using analogy to climb his ladder of inference as a pointless exercise without historical texts showing direct links. Many people have voiced criticisms of the use cultural analogy. Gordon Childe in 1958 ridiculed anyone trying to compare Australian pre-contact populations with prehistoric human ones as a waste of time. Questions arose as to how effective a straight analogous comparison actually was. Populations were separated by large expanses of space, exactly how was it to be expected that people in Northern England, for example, would be expected to behave exactly like Native Americans from the West Coast of North America? How could people be connected through large amounts of time? The uniformitarian argument was that supposed noble savages had existed in a Garden of Eden like state unchanged over many millennia. Even this concept could be made fallible by the theory of cultural ecology in that the environment was in constant flux. 6 A seemingly safer use of analogy is by using it a smaller scale or Middle Range. In this guise questions about how baskets are woven or how fish traps are used can illuminate the lacuna in our own forgotten knowledge. Lewis Binford’s work on activity patterns through artefact scatters in relationship to activity areas has been used effectively at various prehistoric sites stimulating an evergrowing field of ethnoarchaeology. Researchers such as Peter Jordan and Marek Zvelebil advocate studying populations that can be regarded as in situ as hunter-gatherers that are geographically proximate to archaeological populations. If this is so then are we not ourselves geographically proximate to our Mesolithic forebears? Since the 1980s some anthropological, and hunter-gatherer studies in North America, Australia and Africa have shifted from their environmentally deterministic research frames and have become more concerned with individuals and social lives, their extremely complex relationships and cosmologies. This research has shed light on the incredible complex lifeways and also scrutinized and criticized previous abstract concepts of seasonality and mobility. It has been especially critical of environmental determinism and shown how supposed H&G’s can have incredible control over their resources. Yet British Mesolithic studies and therefore hunter-gatherer studies have lagged far behind and social aspects at Star Carr have been little more than speculations although this has changed slightly in the last few years. In my opinion this is because there is no pressure to abandon environmentally deterministic models as there are no present populations to critique the method. The people of the Mesolithic cannot complain about being portrayed as primitive. 7 It is with these criticisms in my mind that I steamed full head into my own use of analogy and my increasing interest into social aspects of Star Carr. SLIDE I wanted to imagine the environment and create a clearer picture of some of the activities around the structures uncovered in the 50s and 80s. After excavating there in 2006 I had been increasingly frustrated with the data presented in Clark’s and Mellars’ publications and built simple computer models to see if anything looked a little different or better. The poor quality of vegetational illustrations also stimulated me to look for modern analogs. SLIDE 1. British sites no deer no beaver. 2. American sites better 3. Brushwood platform 4. American sites no people SLIDE SLIDE I did know of one site that was accessible, contained a mobile foraging community that lived around a reed-fringed lake. I’ve come to call this place Star Crack, a word play because this population is a homeless population in the middle of Brooklyn and several of the individuals smoke crack, in fact a large part of their foraging existence is based around getting drunk or high and occasionally eating. I also regarded this as an interesting experiment in using analogy, as I hadn’t selected a Mesolithic-like population it was un-primitive. At first this was going to be a straight shot at seeing how people moved around, created structures and created refuse and debitage. I wanted to track this project through several seasons and work out how on earth anyone goes about observing someone else. 8 SLIDE Recording beyond photography is problematic because the mental health issues and the location make measured recording impossible. I have talked briefly to some of them and I’ve also been violently threatened. The last thing you want to do around a desperate person is flash an expensive camera. My first observations surrounded 1. How do people access the water’s edge? 2. How are paths made and where do they go? 3. What happens to the reeds over time? 4. How do people live in reeds? 5. My overall impression what is it that makes these people ‘homeless?’ Peter Ucko stated in 1968 that analogy is most useful when it awakens the researcher to personal prejudices when going back to assess archaeological data. It made me rethink some of the platforms and the time frames of construction at Star Carr, the ephemeral nature of some things and the persistence of others. I think I have made a picture in my own mind that influences my interpretation of the site. The use of analogy, including my own, has been flawed. This does not mean that its use has been negated. In fact the continued use of ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological research has changed our concepts and models of the past and highlighted prejudices and suprematist biases within research. Contemporary hunter-gatherer-forager communities seem somehow to be used as the texts that Prehistorians must rely on to interpret our own past and I don’t see a way of conducting research without the use of analogy but the use of 9 analogy must become more nuanced and creative. The use of analogy should be a two-way street and an engagement with the past should also be an engagement with the present. I’ve become increasingly interested in the people themselves, their personalities, their histories and their trajectories. But how does this relate to the Mesolithic beyond a critical attack on standard research questions? I believe the more we include ourselves as proximate to our Mesolithic ancestors in these analogies the more balanced and useful they become and they can have a direct relevance to how our own society is constructed. Due to the ongoing engagement of using analogy I began to question the concepts of settlement, seasonality and mobility -the paradigms of Mesolithic research. This study has highlighted that the distinction is difficult to make between the supposed transience of a mobile group as compared to the domiciled, the people in the park are domiciled and permanent inhabitants the people who return to their apartments around the park are seasonally mobile and transient by comparison. I have begun to research what it is to be homeless and its relationship to mental illness and substance abuse. Homelessness has a long history that can be textually dated back to the 14 th century. Traditional Itinerants, Gypsies and Romanies can all claim ancient origins so there are always people who exist outside of our own civilized hegemony. It has made me question what it means to be domiciled or un-settled. The dichotomy between these two social milieus is directly relevant to the supposed dichotomy of living practices between foragers and farmers. This is supposed to be the difference between Mesolithic and Neolithic subsistence practices defined by an evolutionary model. 10 If this model is correct then any exploration of these social differences should be meaningful. It has made me question the supposed structure of our own society and what it means to be removed from it or to be forgotten by it. How is the Mesolithic really different from other periods in the terms of social structure? Do we attribute terms that make ourselves very different from Mesolithic communities. What happens if we use hunter-gatherer models on our own societies, how different would we appear? I wasn’t sure about this until I read an article in the latest issue of Cambridge Archaeological Review written by Glasgow University staff. This article attempts to define the individual as a social and civil construction that could only be achieved from the 16th century onward. This is a western absurdism and elitism that denies anyone unbounded by our enlightened civilization a right to be individually reflexive. This continues a primitivization of people who are considered outside of our Western society both spatially and temporally. Although homeless people are separated or excluded from society are they still socially and individually constructed by it? Can one become deconstructed from contemporary society and does this deconstruction remove the self from the individual? If society has increased in complexity what happens if this complexity is pared down from a modern community, are we left with a prehistoric community? Do people in prehistory have the right to be individuals? The lives of the homeless and our attitude toward them mimics previous attitudes and plights of indigenous groups that have suffered exclusion, 11 dispossession, resettlement and the ravages of depression alcoholism and drug abuse. Is there some part of our population that may have a proclivity toward alcoholism and homelessness? Evolutionary psychologists often argue that the thousands of years’ humans spent as hunters and gatherers make us adapted to certain life conditions, dietary needs and neurologically determined behaviors. Is it at all possible that the continued appearance of homeless people is an echo of the culture shock that hunter-gatherers in Europe experienced due to increasing settlements of domiciled people and that some people’s need for certain lifeways go unrealized? Does mental illness become exacerbated by domicile and the lack of privacy? How does schizophrenia, for example, manifest in communities around the world? Is mental illness a part of the socially constructed self? If we only study the past for the sake of the past itself or to merely illustrate it then we are in danger of becoming dilettantes. I believe Gordon Childe to be right in expecting archaeology to be a social phenomenon and that research into the past has a lot to inform the present and even the future. As Ucko stated analogy is a way of opening up the mind to possibilities and on a simple level it has aided some of my interpretations of what has been revealed at Star Carr. Importantly this study for me has shown a way that Mesolithic research can be directly relevant to questions surrounding the creation of the individual, social construction and a way to inform our attitudes to the needs of people who fall through the cracks of our own socially constructed lives. Prehistoric research can be directly relevant to psychology, sociology and possibly even social policy as a critique of the prejudices that exist in regards to people that we perceive to be excluded from ourselves. 12