The 2014 Wyoming Checkerboard removal of 1263 wild horses, with

advertisement

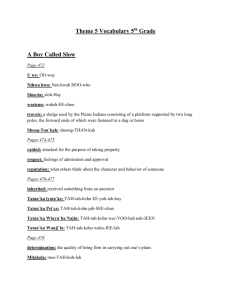

Page 1 of 15 December 21, 2015 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL (blm_wy_checkerboard_hmas@blm.gov) Kimberly D. Foster, Field Manager, BLM Rock Springs Field Office Dennis J. Carpenter, Field Manager Rawlins Field Office Re: Comments 2014 Removal of Wild Horses from Checkboard within Great Divide Basin, Salt Wells Creek and Adobe Town Herd Management Areas, DOI-WY-040EA15-104 Dear Ms. Foster and Mr. Carpenter: Friends of Animals (“FoA”)1 submits these comments in response to the unsigned Finding of No Significant Impact (“FONSI”) for the 2014 Removal of Wild Horses from Checkboard within the Great Divide Basin, Salt Wells Creek and Adobe Town Herd Management Areas, DOI-WY-040-EA15-104. The FONSI was issued in response to a remand by the U.S. District Court for the District of Wyoming (Case No. 14-CV-0152-NDF) which granted the wild horse advocates’ “request for a declaration that BLM’s July 2014 CX is in violation of [the National Environmental Policy Act]” and ordered BLM to “remedy the NEPA deficiencies.” Specifically, the Court determined that “BLM’s conclusion that the gather would not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment is not adequately supported by an analysis of all relevant factors.” FoA is a non-profit international advocacy organization incorporated in the state of New York since 1957. FoA has nearly 200,000 members worldwide. FoA and its members seek to free animals from cruelty and exploitation around the world, and to promote a respectful view of non-human, free-living and domestic animals. FoA regularly advocates for the right of wild horses to live freely on public lands, and for more transparency and accountability in BLM’s “management” of wild horses and burros. 1 Page 2 of 15 BLM’s decision that a mere Categorical Exclusion (“CX”) would fulfill its NEPA obligation to analyze and disclose the impacts of the removal of 1263 horses from the Wyoming Checkerboard was due in large part to commitments the agency made under a Consent Decree signed in 2013 to settle litigation dating back to 1979. However, the settlement, which deprived U.S. taxpayers of over one million acres of public lands formerly available for wild horse use, was a major federal action that significantly affects the quality of the human environment, and analysis of “all relevant factors” regarding the individual and cumulative impacts of the total removal of all wild horses from the Wyoming Checkerboard requires not just an Environmental Assessment (“EA”)/FONSI but the preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement (“EIS”). In addition, the closure of over a million acres of public lands for the benefit of private grazing interests violates the Unlawful Inclosures of Public Lands Act. BACKGROUND The allocation of forage in the Wyoming Checkerboard has been the subject of litigation for at least thirty-five years. In 1909, the Rock Springs Grazing Association (“RSGA”) was established “to assemble the land rights to use the rangeland resources within a portion of the Wyoming Checkerboard roughly 40 miles wide and 80 miles long and containing slightly more than two million acres.”2 While RSGA uses this land primarily for grazing sheep in the winter, “the Wyoming Checkerboard is also crucial winter range habitat for wild horses, although animals can be there year long.“3 It is critical to note that while RSGA is considered to “own or control” more than two million acres within the Wyoming Checkerboard, in fact, over 70% of the checkerboard lands within the three Herd Management Areas (HMAs) at issue here are public lands owned and managed for the public by BLM. Specifically, within the Checkerboard area, BLM manages 61% of the Great Divide Basin HMA, 69% of the Salt Wells Creek HMA, and 92% of the Adobe Town HMA.4 In spite of overwhelming Federal control over the lands in the Wyoming Checkerboard, in 1979, “RSGA met with wild horse advocacy organizations and agreed to allow 1,500 wild horses within the Rock Springs District with only 500 horses [to remain] on the Checkerboard.”5 (Emphasis added.) American Wild Horse Preservation Campaign v. Sally Jewel, 14-CV-0152-NDF (D. Wyo. March 3, 2015). 3 Rock Springs Grazing Ass’n v. Salazar, 935 F. Supp. 2d 1179, 1183 (D. Wyo. April 3, 2013) n-4. 4 See 2015 Environmental Assessment, 2014 Removal of Wild Horses from Checkerboard within the Great Divide Basin, Salt Wells Creek and Adobe Town Herd Management Areas, (2015 Checkerboard EA) at 1. 5 Id. at 7. 2 Page 3 of 15 Despite the agreement, disputes over forage in the Wyoming Checkerboard continued. In 1979, RSGA sued the BLM, seeking removal of wild horses that had strayed onto RSGA’s private lands in the Checkerboard.6 When BLM didn’t remove wild horses from RSGA’s land, due to lack of funding for the wild horse gather program,7 in 1981, RSGA withdrew its consent to “tolerate wild horses on its lands” and sued to compel removal under the Wild Horses and Burros Act (WHBA), 16 U.S.C. § 1134, also known as WHBA Section 4.8 In 1981, the Wyoming District Court ordered BLM to remove all wild horses from the Wyoming Checkerboard except for the number of horses that the RSGA voluntarily agreed to leave in the area. The 1981 Order was amended in 1982 to specify that wild horses above the levels agreed to by RSGA were “excess” under the WHBA § 1332(f).9 BLM managed the Wyoming Checkerboard horses to comply with the Order, and the 1997 Green River Resource Management Plan (RMP) specified that an AML of “1105 to 1600 wild horses will be maintained” among the five herd management areas (Table 15).”10 Table 15, from the 1997 RMP, is reproduced below: Note that the 1997 Green River RMP provided that a minimum of 1105 horses were to be allowed on the HMAs on the Wyoming Checkboard. Specifically, 415 AMLs were allocated to the Great Divide HMA, 205 to the White Mountain HMA, 251 to the Salt Wells Creek HMA, and 165 to the Adobe Town HMA. Mountain States Legal Foundation et al. v Andrus, Civ. No. 79-275K (D. Wyo. 1981). Rock Springs Grazing Ass’n v. Salazar, (D. Wyo. April 3, 2013) n-4. 8 Id. 9 Id. 10 1997 Green River RMP, Table 15, page 72. 6 7 Page 4 of 15 In 2011, RSGA sought a Declaratory Judgment that “RSGA is entitled to enforce the orders of this Court in [Mountain States Legal Foundation et al. v Andrus]”, and that under the WHBA’s Section 4, BLM must remove “all of the wild horses that have strayed onto the RSGA lands and the adjacent public lands within the Wyoming Checkerboard, and all of the wild horses from RSGA’s land within one year.”11 (Emphasis added.) However, on April 3, 2013, the parties signed a Consent Decree that provided that, pursuant to WHBA Section 4, BLM agreed to “remove all wild horses from RSGA’s private lands, including Wyoming Checkerboard lands….”12 BLM also agreed to remove “wild horses from Checkerboard lands” within the Salt Wells, Adobe Town, Divide Basin, and White Mountain HMAs.13 The 2013 Consent Decree set the AMLs for the Checkboard HMAs as follows: Salt Wells/Adobe Town, 200 horses; the Divide Basin, 100 horses; and White Mountain at 205300 horses.14 BLM also agreed to maintain wild horse levels for those HMAs “at the low end of AML.”15 Finally, in the Consent Decree, BLM agreed to initiate NEPA planning to consider the impacts of “zeroing out” both the Salt Wells and the Divide Basin wild horse populations, to allow 225-450 (“or lower”) horses in the Adobe Town HMA, and to maintain the White Mountain HMA at 205 wild horses.16 The AMLs resulting from the 2013 Consent Decree therefore represented a dramatic reduction in the AMLs allocated under the 1997 Green River RMP, both in the number and distribution of wild horses. Specifically, in the Salt River/Adobe HMAs, AMLS were reduced from a minimum of 416 to a maximum of 200 horses; in the Great Divide HMA, AMLs were reduced from a minimum of 415 horses to a maximum of 100. Thus, AMLs agreed to in the 2013 Consent Decree would leave at most 505 wild horses, or less than half of the minimum AML set under the 1997 Green River RMP, in an area encompassing two million acres, including over a million acres managed by the BLM on behalf of the American people.17 In addition to reducing wild horse numbers, the 2013 Consent Decree contemplated drastic changes in the distribution of wild horse populations related to AML updates planned for the Rock Springs and Rawlins Field Office RMPs; both the Salt Wells and Divide Basin horse populations would be gathered to leave zero horses, and Adobe would contain 225-450 horses “or lower,” and White Mountain would be managed for as a nonreproducing herd to maintain a population of 205 wild horses. Therefore, RMP revisions Rock Springs Grazing Ass’n v. Salazar, 2011, Case No. 11-CV-263-NDF (D. Wyo. November 2, 2011). 12 April 3, 2014 Consent Decree, Clause 1. 13 Id. at Clause 5. 14 Id. at Clauses 1, and 4. 15 Id. at Clause 4. 16 Id. at Clause 6. 17 Id. at Clauses 1, 4. 11 Page 5 of 15 contemplated in the 2013 Consent Decree would leave a maximum of 655 horses in a two-million acre area, including over a million acres managed by the BLM for the benefit of the American public. 18 In 2014, BLM removed 1263 wild horses from the Wyoming Checkerboard lands “in accordance with Section 4 of the WHA and the 2013 Consent Decree….”19 To satisfy its NEPA obligations, BLM relied on a CX; as noted above, the U.S. District Court of Wyoming on March 3, 2015, determined that BLM’s reliance on a CX, and conclusion that “the gather would not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment” was ”not adequately supported by an analysis of all relevant factors” and remanded the FONSI so BLM could satisfy its NEPA obligations. In response to the remand, in November of 2015, BLM released the 2015 EA/FONSI that is the subject of this comment. As will be discussed in detail below, BLM’s decision to all but eliminate wild horses from a million acres of public land is a major federal action for which an EIS is required. Further, BLM’s decision to virtually eliminate wild horses from over a million acres of public land, for the benefit of private land owners, violates the Unlawful Inclosures of Public Lands Act. BLM SHOULD CONSIDER ITS OBLIGATIONS UNDER THE NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY ACT A. The 2014 Checkerboard Removal Constituted an Illegal Commitment of Prior to the Completion of NEPA Analysis. NEPA requires that an agency take “a hard look” at the impacts of an action prior to making an irreversible and irretrievable commitment of resources;20 BLM has not done so. The 2015 Checkerboard Removal EA specifically states that the decision to remove horses was not based on NEPA analysis but on various agreements to resolve litigation with a private grazing organization, and yet the Tenth Circuit has held that “if an agency predetermines the NEPA analysis by committing itself to an outcome, the agency has likely failed to take a hard look at the environmental consequences of its actions due to its bias in favor of that outcome, and therefore, has acted arbitrarily and capriciously.”21 The fundamental purpose of NEPA is to improve the decision making of federal agencies by requiring an analysis of the environmental impacts of a proposed action and an exploration of alternatives to that action that would reduce or eliminate such impacts. 42 U.S.C. § 4332. The primary vehicle for this analysis is an EIS. Id. NEPA requires an acting agency to prepare a detailed EIS for federal actions that significantly affect the quality of the human environment, including “(i) the environmental impact of the proposed action, (ii) any adverse environmental effects which cannot be avoided Id. at Clause 6. Purpose and Need, 2015 Checkerboard Removal EA, at 7. 20 Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S 332, 349 (1989). 21 Forest Guardians v. FWS, 611 F.3d 692, 713 (10th Cir. N.M. 2010). 18 19 Page 6 of 15 should the proposal be implemented, [and] (iii) alternatives to the proposed action.” 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C). The EIS is the cornerstone of NEPA. Generally, an agency will prepare an EA to determine whether preparation of an EIS is necessary; in the case of the Wyoming Checkerboard removals, BLM prepared a CX, then an EA, and then determined that an EIS was not required. B. The 2014 Checkerboard Removal is a Major Federal Action for which an EIS is required. An EIS is required for all “major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment.” 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C). The Council on Environmental Quality (“CEQ”) defines “major federal action” to include “actions with effects that may be major and which are potentially subject to Federal control.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.18 (emphasis added). The requirement to prepare an EIS is broad and intended to compel agencies to take seriously the potential environmental consequences of a proposed action prior to taking action. Whether an agency action is “significant” enough to require preparation of an EIS requires “considerations of both context and intensity.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.27. The context of the action includes factors such as “society as a whole (human, national), the affected region, the affected interests, and the locality.” 40 C.F.R. § 1508.27(a). The intensity of an action refers to the “severity of the impact” and requires consideration of several factors, including “[t]he degree to which the effects on the quality of the human environment are likely to be highly controversial”; [t]he degree to which the possible effects on the human environment are highly uncertain or involve unique or unknown risks”; and “[w]hether the action is related to other actions with individually insignificant but cumulative significant impacts.” 40 C.F.R. §1508.27(b). The 2014 Wyoming Checkerboard removal of 1263 wild horses, with no chance of return to wild status, constitutes a significant federal action based on the context and intensity of the action. First of all, as Congress declared, wild horses “are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West; that they contribute to the diversity of life forms within the Nation and enrich the lives of the American people.” 16 U.S.C. § 1331. Second, the public has advocated for the right of wild horses to live freely, and the proposed action, which involves removing over half the horses allowed in the current RMP as well as eliminating reproduction for an entire herd, will be significant to both the wild horses and those who enjoy viewing and studying them. Third, while the impact of the removal of 1263 wild horses may be individually minor, the removal of 1263 wild horses from over a million acres of public land is severe when considered cumulatively. Cumulative impacts, as defined by the CEQ (40 C.F.R. 1508.7), are impacts to the environment that result from the incremental impact of the action when added to other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions, regardless of what agency (federal or non-federal) or person undertakes such other actions. Cumulative impacts may result from individually minor, but collectively significant, actions taking place over time. Page 7 of 15 Cumulative impacts in this case would include the near total removal of wild horses from over a million acres of federal lands, further reduction in the genetic viability of the horses allowed to remain, the addition of yet another 1263 horses to an already overburdened and ineffective wild horse adoption program, and the release of unadoptable horses into expensive and unsustainable long-term holding facilities. This removal represents not only significant direct impacts on the wild horses of the Wyoming Checkerboard, because the horses will be removed from open range and placed in BLM holding facilities, there is a significant cumulative impact on the human environment that BLM failed to consider in its NEPA analysis: the increasing costs of BLM’s ineffective approach to wild horse management. In 2008, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) warned that “the long-term sustainability of BLM’s Wild Horse and Burro Program” was in doubt due in part to the increasing costs of keeping wild horses in holding facilities; the GAO noted that the cost of holding animals “off the range” increased from $7 million in 2000 to $21 million in 2007.22 The cost of maintaining wild horses off the range has continued to grow since GAO’s 2008 warning regarding unsustainable costs of the program. Holding costs were a mere $21 million in 2007; in FY 2012, BLM spent $42.955 million on holding facilities, which constituted 59% of its total wild horse program budget. While the cost of maintaining wild horses removed from the range was astronomical even in 2012, in the last three years that cost has continued to grow; in 2015, BLM budgeted $49.382 million for holding facilities, which represents 65.7%, or almost two-thirds, of the agency’s total wild horse program budget.23 Eliminating wild horses from over a million acres of public land constitutes a significant impact on wild horses, which alone constitutes a significant environmental impact requiring the preparation of an EIS. In addition, with this removal of all but 500 wild horses from over a million acres of public land, American taxpayers are required to bear the costs of an unsustainable approach to wild horse management. And this gather represents a significant departure from wild horse management in the Wyoming Checkerboard; the U.S. District Court of Wyoming noted that “This appears to be the first time RSGA’s checkerboard rangeland has been gathered for removal of all horses without any return.”24 (Emphasis in original.) Therefore, based on the context, intensity, and cumulative effect of this gather demonstrates that this action constitutes a significant impact on the human environment that requires the preparation of an EIS. BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Effective Long-Term Options Needed to Manage Unadoptable Wild Horses issued in October, 2008, http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d0977.pdf 22 Wild Horse and Burros Quick Facts, updated November 24, 2015. American Wild Horse Preservation Campaign v. Sally Jewell, Case No. 14-CV-0152NDF (D. Wyo. March 3, 2015) at 26. 23 24 Page 8 of 15 C. BLM Should Consider Other Reasonable Alternatives. The 2015 Checkerboard Removal EA proposed three alternatives, including Alternative 1, the No Action alternative.25 Alternative 2 was to “remove all the wild horses from the checkerboard lands within the Salt Wells Creek, Adobe Town and Great Divide Basin HMAs” and Alternative 3 was to “remove the wild horses from the checkerboard lands and return them only to the solid block lands within the Salt Wells Creek, Adobe Town, and Great Divide Basin HMAs.”26 In 2014, BLM implemented Alternative 2, to remove all wild horses from the checkerboard lands, resulting in the permanent removal of 1263 wild horses from the Wyoming Checkerboard. Other alternatives considered but eliminated from detailed analysis included changing the established AMLs, removing wild horses to the low AML for each of the HMAs, and using fertility control in lieu of horse removal.27 Each of these alternatives, including the agency’s chosen alternative to remove all wild horses from three existing HMAs in the Wyoming Checkerboard, is predicated upon AMLs set pursuant to an agreement with a private ranching organization that in effect removes all but 500 wild horses from over a million acres of Federal public lands. The 1263 removed horses were transported to holding facilities, to the severe detriment of the horses and at great expense to the American public. An EA or an EIS should provide a full and fair discussion of the issues; it should inform decision makers and the public of the reasonable alternatives that would avoid or minimize adverse impacts or enhance the quality of the human environment.28 The AMLs for these HMAs were set in 1979 based only the demands of a private grazing organization, and with the 2014 Checkerboard Removal BLM affirms that a private grazing association can dictate the use of federal lands to the detriment of both a treasured species protected by statute, and taxpayers who are left responsible for their upkeep. Therefore, Friends of Animals asks BLM to conduct NEPA analysis that considers a full range of alternatives, including at least one alternative that protects wild horses. Reasonable alternatives would include: (1) revisiting assumptions made in the 2013 Consent Decree regarding AMLs; (2) reconsidering AMLs allocated under existing grazing permits; (3) re-evaluating AMLS to meet the needs of wild horses, not just RSGA’s sheep and cattle; and, (4) consistent with BLM’s responsibilities under the WHBA, ensuring that wild horses are considered as “an integral part of the natural system of public lands” and prioritizing wild horses, not sheep and cattle, on herd management areas. 2015 Checkerboard Removal Environmental Assessment, at 11. Id. 27 Id. at 12-13. 28 See 40 C.F.R. § 1502.1. 25 26 Page 9 of 15 Not only are each of these alternatives reasonable, use of any of these alternatives would avoid or minimize adverse impacts to and enhance the quality of the human environment. Thus, NEPA mandates consideration of these alternatives. D. BLM Should Analyze Additional Alternatives Regarding the Positive Impact of Wild Horses, and the Ethical Implications of Its Management of Wild Horses on the Wyoming Checkerboard. NEPA requires BLM to adequately evaluate all potential environmental impacts of proposed actions.29 To meet this obligation, BLM must identify and disclose to the public all foreseeable impacts of the proposed action, including direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts.30 In addition to the issues discussed above, the 2015 Checkerboard EA failed to evaluate the positive impacts of wild horses in the Wyoming Checkerboard, and the ethical impacts of all alternatives. 1. Wild Horses Have a Positive Impact on the Land. The 2015 Checkerboard EA gives the impression that wild horses have an exclusively negative impact on the health of the range.31 However, literature from wildlife ecologists suggests the opposite may be true. A healthy, free-roaming wild horse population serves to fertilize soils, suppress catastrophic wildfires, and contribute to overall ecological stability.32 Nonetheless, the 2015 Checkerboard EA is devoid of any discussion regarding the positive impact of wild horses. In order to make an informed decision and comparison of the alternatives about how to allocate resources and acreage to wild horses or other uses, the BLM must disclose these views and allow the public to comment on them. When given sufficient habitat to roam, there are many ways that wild horses actually support ecosystems on public land.33 Wild horses help spread plant seeds over large areas where they roam. They do not decompose the vegetation they ingest as thoroughly as ruminant grazers, such as cattle or sheep, which allows the seeds of many plant species to pass through their digestive tract intact into the soil that the wild horses fertilize by their droppings. 34 Additionally, other animals depend on horses to make certain 29 See 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2)(C). 30 See 42 U.S.C. § 4332(2); see also 40 C.F.R. §§ 1508.7-1508.8. 2015 Checkerboard EA at 26. 32 Downer, Craig C. "The horse and burro as positively contributing returned natives in North America." American Journal of Life Sciences 2, no. 1 (2014): 5-23. 33 Id. 34 Downer, 11; Duncan, Patrick, ed. Zebras, asses, and horses: an action plan for the conservation of wild equids. Gland: IUCN, 1992. 31 Page 10 of 15 resources, such as water, available. For example, in the winter horses are able to break through the ice to expose water to a variety of species.35 Wild horses also reduce dry, parched and flammable vegetation, and thus can prevent catastrophic wildfires that are on the increase. Further, their ability to build more moisture-retaining soils makes them very important in this respect, since soil moisture dampens out incipient fires and makes the air coating the earth also more moist.36 Wild horses and burros are well adapted to their habitats and fill a significant niche within the North American ecosystem.37 The 2015 Checkerboard EA should be modified to include a fair discussion of reasonable opposing viewpoints, including the beneficial ecological role of wild horses. 2. BLM Must Consider the Ethical Impacts of Its Wild Horse Management. It is time for BLM to recognize that individual wild horses that may be subject to its actions have intrinsic value and this in turn demands that BLM incorporate ethics into its consideration of wildlife management activities and resource planning for the Wyoming Checkerboard wild horse herds. There is a growing recognition among conservationists and biologists that ethics must play a greater role in wildlife policy. 38 “While many agree that ethics must play a central role in any project involving [animals], it is often interesting to note that in many books on human animal interactions . . . there is often no mention of ethics. This needs to change.”39 The same must be said for the way BLM discusses wild horses. 40 Undoubtedly, discussions in the context of policy development about ethics and animals can make some people uncomfortable. But, of course, just a generation ago it was also unheard of for an agency like BLM to incorporate the humane treatment of animals into its decisionmaking process. This has changed dramatically. Inclusion of ethical impacts and considerations allows federal, state, and local decision-makers, as well as the public, to better understand the impact of human actions on animals, and allows for better decisions to be made. Our generation needs to adopt the same approach to educating the decision-makers and the public as to the role of ethics in making decisions to “manage” public lands and animals. Indeed, it is the job of range managers, conservationists, animal advocates and scientists “to work toward public education and information dissemination to address real Downer, 12. Downer, 13-14. 37 Ross MacPhee. “Managed to Extinction.” A 40th Anniversary Legal Forum assessing the 38 See, e.g., Fox, Camilla H., and Marc Bekoff. "Integrating values and ethics into wildlife policy and management—lessons from North America." Animals 1, no. 1 (2011): 126143. 39 Fox and Bekoff, 129. 40 Fox and Bekoff, 128. 35 36 Page 11 of 15 and perceived fears held” by others. What is missing in BLM’s management of the Wyoming Checkerboard herds is the perspective of the animals. The growing body of literature on animal cognition and emotions demonstrates undeniably that animals have interests and points of view. Like us, they avoid pain and suffering and seek pleasure. They form close social relationships, cooperate with other individuals, and likely miss their friends when they are apart. Emotions have evolved, serving as “social glue,” and playing major roles in the formation and maintenance of social relationships among individuals. Emotions also serve as “social catalysts,” regulating behaviours that guide the course of social encounters when individuals follow different courses of action, depending on their situations. If we carefully study animal behaviour, we can better understand what animals are experiencing and feeling and how this factors into how we treat them.41 The 2015 Checkerboard EA should include a serious discussion of the ethical implications of the proposed actions, such as restricting wild horse to artificially low population numbers and depriving them of the right to reproduce. It should also discuss the ethical implication of attempting to roundup wild horses. Wild horses live in highly structured, hard-won family groups and are acutely attuned to dangers in their environment, and wary of humans. 42 These family groups, called bands, generally consist of several females (mares) protected by a dominant male (stallion).43 Once a band is formed, the lead stallion usually watches out for and defends the band and does most of the breeding. The band stallion is protective over the mares and will defend against intrusion, takeover, or theft of females by outside males. Wild horses communicate through a range of vocalizations including neighs, grunts and squeals. Pairbonded animals that have been separated will neigh to locate each other at a distance. Stallions will also use vocal signals to resolve dominance contests before they escalate to extreme physical contact.44 Wild horses are accustomed to roaming freely in the wilderness and are often unable to survive the stress of being captured and held in captivity.45 Indeed, wild horses have a highly refined fight or flight reaction—bodily changes that enhance a horse’s chances of surviving a frightening situation by increasing his/her alertness, capacity for physical exertion and ability to withstand injury.46 Roundups and Fox and Bekoff, 131. Alexandra Fuller, “Mustangs, Spirit of the Shrinking West.” National Geographic Magazine, February 2009; Berger, Joel. "Wild horses of the Great Basin: social competition and population size." Wildlife and behavior and ecology (USA) (1986). 43 NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, “Equus caballus” (2013) 44 Feldhamer, George A., Bruce C. Thompson, and Joseph A. Chapman, eds. Wild mammals of North America: biology, management, and conservation. JHU Press, 2003. 45 Hope Ryden, America's Last Wild Horses. (New York: The Lyons Press, 1999). 46 Bruce Nock, “Wild Horses — The Stress Of Captivity.” Liberated Horsemanship, (2010). 41 42 Page 12 of 15 transportation to holding facilities are “truly disturbing for a species that depends on familiarity for safety and comfort.”47 Under the 2015 Checkerboard Removal EA, all alternatives propose rounding-up wild horses, which directly causes stress to the wild horses as they are often forced to run long distances from helicopters in a state of fear, and on top of that there’s the social unrest from confinement in close quarters with unfamiliar horses once trapped, and the loss of or separation from lifelong herd mates.48 Roundups and subsequent captivity, as proposed in the 2015 Checkerboard EA, can have long term negative effects on the horses and the herd; the dramatic event can compromise a wild horse’s ability to deal with natural stressors.49 Stress from gathers can “have dramatic effects on how an animal functions, behaves and even looks.”50 BLM should consider the effect of all of its actions on wild horse populations as well as individual horses, and their rights to live free of human exploitation and manipulation. THE REMOVAL OF ALL BUT 500 WILD HORSES FROM THE WYOMING CHECKERBOARD TO BENEFIT PRIVATE GRAZING INTERESTS VIOLATES THE UNLAWFUL INCLOSURES ACT As is clear from the 100-year history of forage allocation in the Wyoming Checkerboard, the agency has managed the wild horse herds on the Wyoming Checkerboard to benefit private grazing interests at the expense, both literally and figuratively, of wild horses and of American taxpayers. In 1909, RSGA was established “to assemble the land rights” to use “the rangeland resources” of a portion of the Wyoming Checkerboard “roughly 40 miles long and 80 miles wide.”51 In 1979, BLM allowed RSGA, a private ranching organization, to determine the number of wild horses RSGA would “tolerate” on over two million acres of forage on the Wyoming Checkerboard, in spite of the fact that 70% of that forage, on 1,695,517 acres, is found in Herd Management Areas on public land, while only 30%, or 731,703 acres, is private land owned or controlled by RSGA.52 In addition, BLM set the wild horse AMLs in the 1997 Green River RMP, and drastically revised them in the 2013 Consent Decree, not based on an assessment of range conditions as required under the WHBA, but based on a court order, which did not contemplate that BLM is obligated to comply not only with Section 4 of the WHBA, but also with the Unlawful Inclosures of Public Lands Act (UIA), 43 U.S.C. § 1061, et. seq. Nock, 10. Nock, 9. 49 Nock, 10. 50 Nock, 15. 51 Id. at 3. 52 Id. at 6. 47 48 Page 13 of 15 The UIA, which was passed by Congress in 1885 specifically to deal with conflicts over forage resources in Checkerboard lands in the arid West, makes it unlawful for private landowners to enclose public lands for the benefit of private grazing interests.53 Specifically, UIA Section 1 states: That all inclosures of any public lands . . . constructed by any person . . . to any of which land included within the inclosure the person . . . had no claim or color of title made or acquired in good faith . . . are declared to be unlawful." 23 Stat. 321, 43 U.S.C. 1061. Section 3 further provides: No person, by force, threats, intimidation, or by any fencing or inclosing, or any other unlawful means, shall prevent or obstruct, or shall combine and confederate with others to prevent or obstruct, any person from peaceably entering upon or establishing a settlement or residence on any tract of public land subject to settlement or entry under the public land laws of the United States, or shall prevent or obstruct free passage or transit over or through the public lands: Provided, This section shall not be held to affect the right or title of persons, who have gone upon, improved, or occupied said lands under the land laws of the United States, claiming title thereto, in good faith. 23 Stat. 322, 43 U.S.C. 1063. Congress passed the UIA specifically to prevent the unlawful enclosure of public lands, and the Tenth Circuit has specifically recognized that the prohibition against unlawful enclosures applies not just to people, but to wild animals. In 1988, well before the 2013 Consent Decree was signed, the Tenth Circuit held that the UIA prohibits enclosures that limit access of wild animals, including antelope, to BLM lands: “the UIA prohibition against enclosing public lands was not limited to people….that clause does not contain the word ‘person’ and neither does the Court believe that ‘person’ from the preceding clause should be read into it…According to the statute, “all enclosures of public lands…are...declared to be unlawful.”54 BLM’s removal of all but 500 wild horses from the Wyoming Checkerboard allows RSGA to build a “virtual fence” around two million acres of checkerboard lands, excluding wild horses from over a million acres of public lands owned and managed on behalf of the American people. The language of the 2013 Consent Decree demonstrates that, in spite of the agency’s obligations under the Unlawful Inclosures of Public Lands Act, BLM relinquished the public’s right to the use of over a million acres of public lands. For example, while the Consent Decree notes that RSGA holds only “a grazing permit from the BLM for the See Leo Sheep Co. v United States, 440 U.S. 668, 99 S. Ct. 1403, (1979). See United States ex rel. Bergen v. Lawrence, 848 F. 2d 1502, 1508-1509 (10th Cir. Wyo. 1988); cert. denied, Lawrence v. United States, 488 U.S. 980, 109 S. Ct. 528 (1988). 53 54 Page 14 of 15 alternating sections of the public lands within the Wyoming Checkerboard,”55 the Consent Decree also states: RSGA reached an agreement with wild horse advocacy groups to tolerate 500 wild horses on the Checkerboard in January 1979, once “BLM has proven that they are capable of managing the wild horses with respect to numbers of horses to be allowed in the Rock Springs District.”56 (Emphasis added.) Such language appears not only in the 2013 Consent Decree, but has been carried forward as recently as the 2015 EA for the 2014 Checkerboard Removal, which specifies that, BLM determined that “the appropriate management level for the horse herds on the Salt Wells/Pilot Butte checkerboard lands is that level agreed to by the landowners in that area,” and that “[a]ll horses on the checkerboard above such levels [set by the private landowners] are ‘excess’ within the meaning of 16 U.S.C. 1332(f).”57 While the U.S. District Court of Wyoming in 1979 ordered BLM to “remove all wild horses from the checkerboard grazing lands except that number with the RSGA voluntarily agrees to leave in said area,” and the 2013 Consent Decree specifically references the Unlawful Inclosures of Public Lands Act, BLM has never addressed a critical issue central to its obligation to manage wild horses on behalf of the American people: setting AMLs based purely on the needs of a private grazing organization that incorporated for the purpose of controlling two million acres, well over half of which are owned by the Federal government, constitutes the very type of “enclosure” of Federal public lands made unlawful under the UIA. Sincerely, Andrea Gelfuso Andrea Gelfuso Public Lands Attorney Wildlife Law Program Friends of Animals 2013 Consent Decree at 2. Id. 57 2015 Checkerboard Removal EA at 2, citing Mountain States Legal Foundation v. Watt, No. C79-275K, Order Amending Judgement Pro Tunc (D. Wyo. February 19, 1982). 55 56 Page 15 of 15 Western Region Office 7500 E. Arapahoe Rd., Suite 385 Centennial, CO 80112 andreagelfuso@friendsofanimals.org 720-949-7791