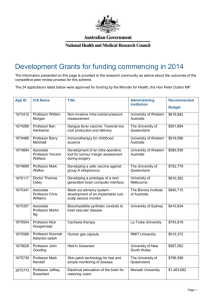

linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending

advertisement

A road is not just a road: linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending: QCOSS Submission to the Queensland Infrastructure Plan July 2015 About QCOSS The Queensland Council of Social Service (QCOSS) is the state-wide peak body for individuals and organisations working in the social and community service sector. For more than 50 years, QCOSS has been a leading force for social change to build social and economic wellbeing for all. With almost 600 members, QCOSS supports a strong community service sector. QCOSS, together with our members continues to play a crucial lobbying and advocacy role in a broad number of areas including: sector capacity building and support homelessness and housing issues early intervention and prevention cost of living pressures including low income energy concessions and improved consumer protections in the electricity, gas and water markets energy efficiency support for culturally and linguistically diverse people early childhood support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and culturally and linguistically diverse peoples. QCOSS is part of the national network of Councils of Social Service lending support and gaining essential insight to national and other state issues. QCOSS is supported by the vice-regal patronage of His Excellency the Honourable Paul de Jersey AC, Governor of Queensland. Lend your voice and your organisation’s voice to this vision by joining QCOSS. To join visit www.QCOSS.org.au. 2 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending Table of Contents 1. Introduction............................................................................................... 4 2. Better Governance and Independent Assessment of Infrastructure ......... 5 3. A road is not just a road, a hospital is not just a hospital .......................... 6 4. How to incorporate social considerations into the Infrastructure Plan ...... 7 4.1. Social Housing ................................................................................... 7 4.2. Local economic development ............................................................ 8 4.3. Measuring social infrastructure need and outcomes .......................... 9 4.4. Financing infrastructure and capturing value for public objectives ... 10 4.5. Partnering with the community sector .............................................. 13 5. Concluding comment .............................................................................. 14 6. Appendix 1: Infrastructure responsibilities by level of government ......... 15 3 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending 1. Introduction Government spending on infrastructure is a way of boosting productivity, and cultivating longer-term economic growth and community wellbeing. Low commodity prices and a generally slowing economy has seen infrastructure spending drop in recent years, prompting a national debate about better ways to finance infrastructure and target limited funds to get the most bang for our buck. The bulk of the infrastructure spend in 2014, in both the Federal and Queensland budgets, went on roads. While efficient transport is important, this should not be at the expense of other critical infrastructure that allows cities, towns and small communities to work. Decisions on infrastructure needs to factor in that judicious investment in social and community infrastructure can deliver both social and economic outcomes. Equally, well-chosen economic infrastructure provides opportunities for industry while supporting communities that have a range of incomes, backgrounds and demographic characteristics to access jobs and other community resources in a fair and equitable way.1 These social outcomes are important in and of themselves, but also because social cohesion is linked to economic development, investment attractiveness and business competitiveness. Furthermore, when communities are healthy, they consume less of the welfare budget. The Grattan Institute’s, John Daley, reminds us that “infrastructure only increases productivity if it is the right infrastructure in the right place, provided at the right price”.2 A failure to link infrastructure spending to broader social goals will see Australia and Queensland spending its limited funds on the wrong infrastructure, in the wrong places, potentially exacerbating rather than alleviating existing needs. QCOSS welcomes the opportunity to make a submission to the Queensland Infrastructure Plan. On current trends the Australian population is forecasted to be almost 40 million by 2055, it is important that planning for major long lived infrastructure3 happens now. Particularly QCOSS is keen to ensure that the likely billions of dollars spent by future governments as a result of the Infrastructure Plan is more closely aligned with the broader socio-economic objectives of community development and cohesion. This is vital as we need 1 Infrastructure Australia (2013) National Infrastructure Plan 2 Daley, J (2013) Is there still a budget emergency, speech to the National Press Club 9 October 2013 3 Distinctions have also been made between hard and soft social infrastructure. Hard infrastructure being buildings and equipment and soft infrastructure being more intangible contributions that enhance both individual and community well-being through equitable, accessible and appropriate community services, skills, knowledge and abilities, local networks, relationships and collaborative responses. 3 This paper is primarily concerned with achieving a better result from the billions of dollars spent on hard infrastructure (both social and economic) each year. But the soft infrastructure is also part of the story. It is the soft infrastructure that makes the hard infrastructure work, and this needs to be considered in any investment decision 4 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending to prepare for a more equitable future4. Well-chosen infrastructure investments now can help alleviate future disadvantage caused by rising poverty and income inequality in Australia. In this submission, QCOSS makes a number of comments regarding the need for good governance and independence of assessment, it then documents how social considerations can be incorporated into the Infrastructure Plan. 2. Better Governance and Independent Assessment of Infrastructure Last year, concerns about costs, competitiveness and productivity in the provision of infrastructure sparked a Productivity Commission Inquiry into Public Infrastructure. The Inquiry identified poor project selection and inadequate planning as major constraints on building infrastructure in Australia. It suggested a range of reforms to overcome barriers to private investment, ensure more efficient project selection, procurement and prioritisation and improve funding and financing mechanisms. There is also an independent national body which advises Australian Governments on priorities for infrastructure spending, Infrastructure Australia. Infrastructure Australia has just completed a process of undertaking an audit of all the infrastructure needs in Australia to prepare a national 15 year plan. Concerns have been expressed that Infrastructure Australia processes get bypassed for political reasons. The 2014-15 budget provided funding for 36 major named infrastructure projects but only four had been assessed by Infrastructure Australia, and only seven appear anywhere on their priority list. 5 New governance arrangements recommended by the Productivity Commission may alleviate this problem. QCOSS therefore welcomes the State Government’s process of developing a new State Infrastructure Plan, due in February 2016. It also notes that a new statutory body, Building Queensland, is being created to provide independent advice to government on infrastructure priorities and will contribute to this plan. 4 The OECD notes that poverty is on the rise in Australia with 14.4 per cent of the population unable to make ends meet, compared with the OECD average of 11.3 per cent OECD (2014) Society at a glance 5 Dossor, R. (2015) Infrastructure Expenditure. Parliamentary Library, Parliament of Australia. 5 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending 3. A road is not just a road, a hospital is not just a hospital The Productivity Commission Inquiry supports the community sector’s observations on the link between social infrastructure and economic outcomes. In its recent Inquiry, it noted that social infrastructure (such as schools, hospitals and social housing) provide important direct benefits to individuals and can also have broader economic implications. For example, improved education and health outcomes can lead to increased workforce participation and labour productivity. Conversely economic infrastructure (such as communications and transport) can provide a direct impact on business productivity, but also can contribute to a range of social outcomes such as social connectivity and local community renewal. Economists sometimes call these agglomeration spillovers. The Productivity Commission gave the example of transport networks: “Effective transportation networks deepen markets. They bring consumers closer to more businesses, and they bring workers in contact with more opportunities. These deeper markets and connections promote competition. They promote greater specialisation by both firms and workers. And they promote innovation and a more dynamic economy”.6 Capturing these broader, often less obvious, effects is not easy but essential to understanding the cost-benefit of various infrastructure choices. What is needed is an holistic appreciation of the full range of impacts of an infrastructure investment before decisions are made on the merits of a project. In doing this, the relative values of different types of public infrastructure, for example roads versus public transport, need to be weighed up, taking into account long term objectives and broad societal impacts. Some countries do this by ensuring that all infrastructure spends are rooted in the country’s broader socioeconomic objectives. In Switzerland, for example, the national infrastructure authority starts its planning with the overarching objectives around economic, ecological and social sustainability and develops specific strategies focused on these objectives.7 Taking a ‘networked’ approach - making decisions as part of a system and considering potential network effects, will ensure effective project selection. Planning authorities do attempt to do this. For example, there are regulations on developers requiring economic and social impact assessments. But current arrangements are clearly not working well. A recent study found that housing was unaffordable for jobseekers in all 40 regions in Australia where they are most likely to find employment.8 Long-term social objectives are not being supported if affordable housing investments are not linked with economic 6 Productivity Commission (2014) Inquiry into Public Infrastructure 7 Dobbs, R. et al (2013) Infrastructure Productivity: how to save $1 trillion a year. McKinsey Global Institute. 8 Australians for Affordable Housing (2013) Opening Doors to Employment: Is housing affordability hindering job seekers. 6 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending opportunities. Similarly, investment in schools, hospitals, community facilities and other job-creating infrastructure, is not helpful without a complementary investment in public transport. Taking a networked approach can also lead to better use of existing infrastructure. We often hear of white elephant investments - infrastructure that operates below capacity. A networked approach is about looking at what exists and what can go together with existing infrastructure to ensure the maximum economic and social return on investment while minimising environmental impacts A suite of complementary initiatives, or a networked approach, can produce greater returns to each individual investment. This requires a realistic assessment of the full range of infrastructure that will be required to make a difference, along with a commitment to providing both the capital and the recurrent resources to manage the infrastructure. The example below describes a situation where such an approach was not taken. Case study: Macquarie Fields An oft-cited example of a failure to take a networked approach is the Macquarie Fields development in Sydney. When it was developed in the 1970s and 80s some basic hard infrastructure was provided such as roads, shops and affordable housing, but other hard social infrastructure needs were omitted (such as a community centre) and little consideration was given to ‘soft’ infrastructure requirements such as access to employment and transport, demographic diversity and the establishment of local services and strategies that develop community cohesion. For many years this suburb was a crime hotspot with double the national average unemployment. It was not until a 2006 Government Inquiry into riots in the suburb that adequate investments were made in community infrastructure, along with an investment in the coordination of that infrastructure. (Adapted from Casey 2005, Establishing Standards for Social Infrastructure) 4. How to incorporate social considerations into the Infrastructure Plan The following considerations encourage a networked approach to infrastructure spending to ensure the widest range of opportunities and impacts are considered. 4.1. Social Housing At the Commonwealth level, the infrastructure funding focus continues to be on roads and freight rail, in line with their traditional responsibilities. The Queensland Government also spends most of its infrastructure budget on transport and roads - $5.4 billion in 2014-15. The last Queensland budget also included about $2.2 billion for 10 new schools and 7 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending development/redevelopment of hospitals and a little under half a billion in other infrastructure improvements for the regions such as roads, bridges, flood mitigation infrastructure and waste recycling. A key issue for the community sector in the infrastructure debate is that social and affordable housing, while clearly fitting the definition of public infrastructure9, is not currently dealt with under infrastructure priorities at Federal or State levels. ACOSS points out that if housing continues to be viewed by governments as a welfare issue, rather than an infrastructure issue, the existing problems in the Australian housing market will continue to impede economic activity, participation and productivity, and the market will continue to fail to provide adequate housing for all.10 This issue underlines the need for a broader conception about the socio-economic value and cost of infrastructure projects. 4.2. Local economic development Infrastructure spending within a local area opens up a range of opportunities for local economic development. By promoting and supporting local enterprise in project selection and procurement, communities experiencing economic disadvantage can achieve more local circulation of money and strengthen linkages in their local economies. Infrastructure investment can thus create a positive multiplier effect.11 These economic development opportunities are particularly important in rural and regional communities facing disadvantage and Indigenous communities where infrastructure investments are planned to address historic neglect. The North Australia Indigenous Experts Panel have pointed out that infrastructure investments must directly address improvements in human and social capital that include but go beyond the basics of health and education, to encourage innovation in livelihoods based on ownership of land and use and management of resources. They call for greater flexibility to match government programs of all sorts to deeper understanding of local context and aspirations.12 Part of this is considering what makes the infrastructure viable after it has been built. Community buildings are sometimes planned and built without due consideration to whether it is what the community wants and whether the community can finance the management and on-going operation of the Mission Australia’s submission to the Productivity Inquiry into Public Infrastructure points out “Housing is a central piece of a country’s economic infrastructure and productivity. A poorly operating housing market creates drag on productivity and distorts the jobs market, as people’s housing options impact their employment opportunities. Government has a primary role and responsibility for decisions regarding the provision of social and affordable housing decisions and is the primary funder of their provision. Consequently, social and affordable housing meets the proposed elements required to be considered public infrastructure” 9 10 ACOSS et al (2015) Affordable Housing Reform Agenda: Goals and recommendations, an overview for reform. 11 For more on this concept see the New Economics Foundation’s Plugging the Leaks Framework www.pluggingtheleaks.org 12 NAILSMA (2013) Indigenous futures and sustainable development in North Australia 8 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending asset.13 Poorly timed, designed or placed developments put pressure on other levels of government or portfolios to provide services 14, and represent a missed opportunity for local economic development. It is not just bricks and mortar assets that need to be considered. Mission Australia suggests that infrastructure supporting online technology could a significant role to play in transforming regional and remote communities and that an assessment of the value of public investment in online infrastructure would be informative. 15 For local communities to have genuine opportunities to benefit financially from investments in their own communities, there needs to be a more level playing field to allow local community service organisations and small and medium enterprises to bid for contracts or participate in supply chains. This is an important element of ‘sustainable procurement’. QCOSS recommends that the Infrastructure Plan should investigate the policy levers and other mechanisms to ensure local infrastructure investments maximise the ongoing economic benefits for local communities. QCOSS also recommends that a more level playing field be created to allow local players to bid for infrastructure procurement contracts or sub-contracts through consortia. 4.3. Measuring social infrastructure need and outcomes In the past decade, governments have begun to formulate indicators of wellbeing and progress, and communities themselves have begun to see this as an important way to understand and monitor their regional issues. In Queensland, for example, QCOSS has developed an Indicators of Poverty and Disadvantage Framework and Community Indicators Queensland (CIQ) has developed a framework to support the creation and use of local community well-being indicators. Economic activity, employment, skills, housing affordability, transport accessibility, community connectedness, cultural and sporting activities can be assessed using surveys, demographic data, qualitative tools and other information. QCOSS has successfully modified this framework to assess community resilience in three pilot communities.16 Such research can provide a starting point in understanding gaps in infrastructure, based on socio-economic aspirations, as assessed by the communities themselves. But there is still a way to go before we have a widely-accepted mechanism for identifying and measuring the infrastructure needs of the community. QCOSS recommends that the Infrastructure Plan sets out what needs to be done to ensure that projects address clearly defined community needs. 13 Casey S. (2005) Establishing standards for social infrastructure. University of Queensland. Brisbane 14 Infrastructure Australia (2008) A report to the Council of Australian Governments 15 Mission Australia (2015) Mission Australian Submission to the PC Inquiry into Public Infrastructure 16 QCOSS (2012) Resilience profiles project 9 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are usually used to as a decision making framework to identify potential preferred projects in a logical and consistent way. CBA encourages decision makers to take into consideration all economic costs and benefits of a project and uses economic efficiency criteria to select and prioritise projects. The Productivity Commission notes that to provide a reliable guide to what is in the overall interest of the community, a cost−benefit framework needs to be broad, taking into account all relevant economic, social and environmental outcomes.17 Evaluation methodologies such as Social Return on Investment provide tools for measuring and accounting a broader concept of value, taking into account social, economic and environmental factors. Use of these tools is providing evidence that investment in public infrastructure can lead to long term savings when the full impact of the investment is quantified (see example below). The Infrastructure Plan and independent assessments by Building Queensland must ensure that the cost-benefit framework goes beyond the purely economic efficiency criteria and include also the long term social and environmental outcomes. Case study: Going Places Program The Going Places program involved homeless outreach to move long-term homeless people into sustainable housing. The investment from government was $3.6 million over 4 years but the program delivered quantified benefits to society of over $33 million over 4 years and avoided further costs of $27.4 million over 4 years to government. For every $1 invested, the government saved $5.10 in public services no longer required. The savings reflect reduced need for crisis accommodation, incarceration, court proceedings, police time, diversionary services, time in hospital, and participants being able to support their own children amongst other tangible, quantifiable benefits. (Mission Australia submission to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Public Infrastructure) 4.4. Financing infrastructure and capturing value for public objectives In these budget-constrained times, the major challenge for planning and delivery infrastructure will be how to finance infrastructure. Certainly in NSW financing infrastructure will be through asset sales or leasing and the Commonwealth Government is encouraging this approach through incentive payments for states that sell assets and redirect the funds 17 Productivity Commission (2014) Inquiry into Public Infrastructure 10 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending into more productive infrastructure (asset recycling). The new Queensland Government has a mandate not to sell assets so will not go down this path. They are looking instead at merging state-owned assets though to create efficiencies and savings. Another way to fund a higher spend by governments is for the community to pay higher taxes. Ken Henry noted in his comprehensive review of the tax system, that public goods should generally be funded from broad-based taxes on income, consumption or land.18 Given that Australians have the fifth lowest tax burden of all 34 OECD countries,19 there is some scope for financing infrastructure investments through the tax system, however achieving tax increases is always a politically-charged task. As the Commonwealth Government has the majority of tax raising powers, it together with the States will need to make some hard choices and have a genuine dialogue with the Australian people about what we want to achieve through infrastructure investment and how to finance this expenditure. The challenge is to convince the public to differentiate between short term spending and long term investments that improve quality of life for all Australians including intergenerational, and generate savings in the long term. The Infrastructure Plan Directions Paper calls for innovative ways to fund and finance infrastructure. There are levers which the States’ have in the planning and development area and should be investigated further. For example, in the UK there has been a greater emphasis on capturing ‘planning gain’ for public objectives. Since the 1990s, the use of planning obligations has shifted away from requiring developers to finance narrowly defined off-site infrastructure (such as access roads), toward financing infrastructure and services that provide broader community benefits - the most notable being affordable housing.20 In Australia in 2009, the ACT, NSW and Victoria allowed contributions to be levied from developers for a wide range of capital works associated with economic and social infrastructure. At the time planning regulations in Queensland and some other states were not as flexible. See Table 1 below. 18 Commonwealth of Australia (2011) Australia’s Future Tax System Australian treasury (2013) “Australia’s tax system compared with the OECD” Pocket guide to the Australian Tax System 19 20 Productivity Commission (2014) Inquiry into Public Infrastructure 11 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending Table 1: Public infrastructure eligible for mandatory contributions (excluding basic infrastructure) NSW Vic Qld WA SA Tas ACT NT UK Parks Education Trunk Roads Childcare centres Community centres Recreation facilities Sports grounds Protection Housing (Reproduced from Chan (2009) “Public Infrastructure Financing: An international perspective”. Please see original table on page 126 for notes on allowances and limitations) The Productivity Commission points out that there are pros and cons in relying on developer contributions for community infrastructure. They say there can be costs to society if local planning authorities misuse planning permission as a bargaining, rather than compliance, tool. Also, when increased costs get passed on to home buyers, this can effect housing affordability for owners and renters. Betterment levies are another way of capturing the value from the beneficiaries of development. Research at Curtin University has shown that up to 60 per cent of the cost of a light rail project could be funded by putting aside the windfall tax revenues received as a result of building the rail due to increases in land values (stamp duty, capital gains taxes, rates). The underlying logic is that the benefits from local infrastructure are reflected in higher property values and business activity, and a betterment levy provides a means of readily capturing part of those benefits to fund the infrastructure.21 Such innovative funding approaches are yet to be tried in Australia, and in a 21 Productivity Commission (2014) Inquiry into Public Infrastructure 12 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending budget constrained climate, its feasibility should be explored as a viable funding mechanism.22 Public infrastructure funded through user pays mechanisms often have distributional impacts whereby low income households face greater financial impacts than higher income ones. Therefore, QCOSS encourages the Infrastructure Plan to investigate innovative and equitable ways of financing public infrastructure. 4.5. Partnering with the community sector The community sector is uniquely positioned to participate in infrastructure planning and delivery. Community organisations can leverage resources, including volunteer and ethical investor contributions, to address community interests and meet needs to which markets do not respond or are not designed to serve, and they usually have a deep understanding of the challenges that face their community. In the community housing sector for example the not for profit sector has been shown to be able to deliver a higher level of operational efficiency and service quality compared to their public sector counterparts, and tenants rate community housing as superior to public housing in meeting their needs.23 Work has begun around the country on transferring responsibility for social housing dwellings to community housing providers (CHPs) as a way of diversifying social housing, improving efficiency and promoting community renewal. In Queensland transfers have been confined to management outsourcing, rather than asset handovers. Asset ownership would give CHPs greater scope to grow and innovate, but there are a range of technical barriers to any large-scale handover and concerns that this would have a major impact on the state government’s fiscal position.24 Social impact investing is another way the community sector can access capital to invest in social infrastructure and other community needs. Social impact investment is finance provided to social sector organisations by investors that expect to both get their money back and create social impact. Depending on the arrangement, investors may also expect a financial return on their investment. Social impact bonds involve ethical investors (philanthropists and commercial lenders) providing the funds to finance a program delivered by the community service sector. The Government then repays the investors based on the achievement of agreed outcomes in areas such as health, education and employment. Social impact bonds are being used successfully in the 22 Green, J. (2014) Mass transit infrastructure spend missing from budget. Curtain university 23 Infrastructure Partnerships Australia (2014) Submission to NSW Inquiry into Social, Public and Affordable Housing 24 Pawson, H., Milligan, V & Hulse, K., (2013) Public housing transfers: past, present and prospective. AHURI. A range of other benefits and barriers to public housing transfers are also discussed in this report. 13 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending provision of social services, but they are yet to be applied in the purchasing of infrastructure. There are also opportunities for the community sector to work with private sector providers to deliver social benefits as an integral part of infrastructure being procured. Infrastructure Australia suggests that governments could combine contracts for providing whole-of-life infrastructure outcomes with contracts for social, health and education outcomes. Such arrangements would involve establishing strong and long-lasting partnerships between community sector and private sector organisations. 5. Concluding comment This paper provides a starting point for discussions and exploration of ways to get a better link between public expenditure on infrastructure and social outcomes and collaborative partnerships between governments, the private sector and the community sector to maximise the benefits of their contribution. The best and most useful social and economic infrastructure investments will be based on a networked approach, with deep consideration of broad social impacts and uses, and complementary investments that improve the return to each individual investment. Having well-accepted measures for establishing needs and outcomes will be critical to making a case. Involving the not-forprofit sector in selection and delivery of infrastructure will ensure more efficient operations, and assets that are rooted in community needs and aspirations. 14 / 1 July 2015 Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending 6. Appendix 1: Infrastructure responsibilities by level of government Level of government Economic infrastructure Social infrastructure Commonwealth Aviation services (air navigation etc.) Tertiary education Telecommunications Postal services National roads (shared) Public housing (shared) Health facilities (shared) Local roads (shared) Railways (shared) State Roads (urban, rural, local) (shared) Railways (shared) Educational institutions (primary, secondary and technical) (shared) Ports and sea navigation Childcare facilities Community health services (base hospitals, small district Electricity supply hospitals, and nursing Dams, water and sewerage homes) (shared) systems Public housing Public transport (train, bus) (shared) Sport, recreation and cultural facilities Aviation (some regional airports) Libraries Public order and safety (courts, police stations, traffic signals etc.) Local Roads ( local) (shared) Childcare centres Sewerage treatment, water and drainage supply Libraries Aviation (local airports) Electricity supply Public transport (bus) 15 / 1 July 2015 Community centres and nursing homes Recreation facilities, parks and open spaces Linking social outcomes to infrastructure spending